Peer Reviewed

Fact-checking Trump’s election lies can improve confidence in U.S. elections: Experimental evidence

Article Metrics

10

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

As the 2020 campaign unfolded, with a mix of extraordinary embellishments and outright falsehoods, President Trump’s attacks on the integrity of the U.S. electoral system grew louder and more frequent. Trump-aligned Republican candidates have since advanced similar false claims in their own campaigns in the lead-up to the 2022 midterm elections. Scholars, election officials, and even fellow Republican leaders have voiced concerns that Trump’s rhetoric represents a profound threat to the well-being of U.S. democracy. To investigate the capacity for fact-checking efforts to repair the damage incurred by election-related misinformation, in the weeks before the 2020 election, we fielded a survey experiment on a nationally representative sample to test whether exposure to fact-checks of Trump’s false claims increased participants’ confidence in the integrity of the U.S. election and affected their voting behavior. Although our pre-registered analysis offered no evidence that corrections affect voting behavior, our findings do show that exposure to these fact-checks can increase confidence in the integrity of the 2020 U.S. election. However, the effects varied significantly by partisanship, with these changes concentrated among Democrats and Independents.

Research Questions

- Will exposure to fact-checks correcting false statements by President Trump regarding the integrity of the 2020 election increase confidence in the election?

- Will the effects of exposure to fact-checks correcting false statements by President Trump regarding the integrity of the election affect self-reported intention to vote and actual turnout?

- Do the effects of exposure to fact-checks on the election-related attitudes and behavior described above vary by partisanship?

Essay Summary

- In the weeks before the 2020 election, we administered a survey experiment on a nationally representative sample to evaluate the effects of multiple factual corrections of Trump’s election-related lies. Participants were randomly exposed to see six PolitiFact corrections of Trump’s lies (treatment) or none (control). Rather than study effects on belief accuracy, we focused on election-related attitudes and behavior.

- We found that exposure to these fact-checks increased confidence in the integrity of the 2020 U.S. election. However, these effects varied significantly by partisanship, with changes concentrated among Democrats and Independents, who became more confident in elections as a result of corrections.

- Republicans became neither more nor less confident with exposure. Although the corrections did little to repair the damage these falsehoods did to Republicans’ confidence in the election, these findings accord with recent work demonstrating that evidence does not generate attitudinal “backfire” effects, wherein exposure to evidence generates attitudinal effects contrary to the direction implied by the evidence (Guess & Coppock, 2020).

- We also investigated whether fact-checks affected voting behavior by matching treatment status to voter files from the 2020 election. On this outcome, our pre-registered analytic strategy finds no evidence that corrections affect voting behavior. However, investigation of the data suggests that this research question merits further investigation.

- Our results offer cautious optimism about the power of multiple factual corrections to change attitudes about issues of fundamental importance to democracy. Lies about elections can reduce confidence in elections (Berlinski et al., 2021). Correcting those lies can improve confidence in the integrity of the electoral system, at least among some subsets of voters.

Implications

Skepticism about the fairness of elections has deleterious effects on voters’ democratic attitudes and behaviors. For example, doubts about the integrity of an electoral system diminish citizens’ political trust and general satisfaction with their government’s democratic performance (Norris, 2014; Norris, 2019). Perceptions of electoral integrity play a central role in these evaluations because elections are a core component of how voters define and understand democracy (Ferrín & Kriesi, 2016), and because elections are among the more tangible and visible mechanisms available to citizens to assess the fairness and legitimacy of their political system (Norris, 2019). It is these attitudes that also influence citizens’ propensity to turnout to vote (Bailard, 2012; Birch, 2010; Bratton & Van de Walle, 1997; Domínguez, 1998; Hooghe et al., 2011). As Birch (2010) put it: “If voters fear that polls are corrupt, they have less incentive to bother casting a vote; participating in a process in which they do not have confidence will be less attractive, and they may well perceive the outcome of the election to be a foregone conclusion” (p. 1603).

Previous scholarship has also made clear that belief in Trump’s falsehoods can be effectively rebutted (Wood & Porter, 2019), even among his supporters (Porter et al., 2019). These studies showed that factual corrections of Trump’s misstatements improve factual accuracy. In other words, fact-checks induce individuals to become more factually accurate. Extant research, however, has made limited progress on a related question: Can corrections affect related attitudes and behaviors?

In addition to there being less research on the effects of fact-checks on downstream attitudes, the research that does exist offers mixed conclusions. Consistent with the continued influence effect (Lewandowsky et al., 2012), some have demonstrated that corrections are not enough to overcome the negative effects of misinformation on attitudes. Thorson (2016) found that, even subsequent to correction, misinformation lingers powerfully enough to affect related attitudes. Porter et al. (2019) and Nyhan et al. (2020) observed corrections of Trump misstatements improving factual accuracy, including among Republicans and Trump supporters, without impacting attitudes toward Trump and related policies. More recently, corrections have increased factual accuracy about COVID-19 vaccines but have not improved attitudes toward vaccines or increased willingness to receive a vaccination (Porter et al., 2022). During the 2016 election, for example, correcting Trump’s false claims about crime improved factual accuracy, even among his supporters, but had no effects on support for Trump (Nyhan et al., 2019). Similarly, during his presidency, fact-checking Trump’s falsehoods about climate change made people more accurate (again including his supporters), but it did not cause shifts in support for climate-related policies (Porter et al., 2019). Such findings suggest that debunking Trump’s false claims may improve factual accuracy (Chan et al., 2017) without affecting related evaluations and attitudes.

In contrast to these previous studies, our experiment demonstrated that factual corrections improved election confidence even amidst a deeply contentious election, in which the incumbent president repeatedly lied about the integrity of the election. Thus, not only can corrections improve belief accuracy, but our findings demonstrate that they can also affect attitudes, even on the topic of election integrity during a heated presidential election. While these effects are not large by conventional standards, it is important to keep in mind that pre-registered experiments such as ours tend to yield smaller effects relative to studies that were not pre-registered (Schäfer & Schwarz, 2019), in part because of the analyzing, reporting, and publishing biases inherent to non-pre-registered studies. As false claims about electoral integrity continue to be voiced by Trump and his allies, our findings provide reason to be cautiously optimistic about the capacity of factually accurate information to undo some of the damage these falsehoods wreak.

However, the attitude effects are not uniform across party lines. The effect on election confidence was moderated by partisanship, with the effect concentrated among Democrats and Independents, while Republicans were unaffected. To be clear, Republicans did not respond to these fact-checks by taking their cues solely from the recitation of Trump’s falsehoods, which would have further suppressed their confidence in the election. While scholars have voiced concern that factual updating does not necessarily bode well for democratic competence (Bisgaard, 2019), we find no evidence of corrections to Trump’s false claims backfiring; Republicans did not become less confident in elections as a result of fact-checks.

What explains our ability to detect attitudinal effects of corrections, which prior studies have failed to do? It is possible that attitudes toward elections are unusually susceptible to fact-based interventions (Mernyk et al., 2021). It is also possible that our attitudinal effects are owed to the number of corrections we displayed to treated participants. Under this explanation, in an age of polarization, political attitudes are apt to change only if a more-than-minimal set of information is provided to a respondent. Otherwise, factual information may be insufficient to affect attitudes. This finding corresponds with other persuasion research, which shows that the quantity of messages matters (Sides et al., 2021; Spenkuch & Toniatti, 2018).

In theoretical terms, our study makes a useful contribution to our understanding of misinformation and corrections by demonstrating that, in contrast to previous studies, fact-checks can affect downstream attitudes under certain conditions. Practically, our study provides actionable insight for campaigns and organizations seeking to increase trust in American elections, particularly in electoral contexts where one or more of the candidates continue to espouse electoral falsehoods. For example, these findings suggest that targeting Independents with corrections to electoral misinformation may be particularly consequential, particularly in light of the outsized role these voters often play in electoral outcomes. However, doing so may require exposing people to multiple fact-checks about the issue.

Although Republican attitudes did not shift, it is somewhat reassuring that their attitudes also did not backfire by generating attitudinal effects contrary to the direction implied by the correction (corroborating Guess & Coppock, 2020). This means that, at the very least, their confidence in elections is not worse off for having seen the corrections; that said, we anticipate future research will test ways of moving election-related attitudes among this group specifically.

Several other questions remain. It is unclear whether, among Republicans, the tendency to believe election-related lies and/or resist factual corrections targeting election-related lies will be as strong when those falsehoods are not coming from Trump. Perhaps most important of all, under what circumstances are these findings most likely to generalize to the outside world? The treatment we tested here is especially strong. Participants were not just exposed to six fact-checks but were compelled to spend at least 30 seconds on each one before they could move forward. Given the sparse prior evidence substantiating corrections’ capacity to shift attitudes, we anticipated that a strong treatment may be necessary. We opted not to also randomize exposure to fewer or a single correction at a time, in part due to statistical power concerns. Thus, we cannot say what amount of factual information constitutes the threshold point after which fact-checks can change attitudes, nor was this the objective of the present study. We look forward to future work that disentangles this open question. Testing other sources or formats of the fact-checks are additional potential avenues for research that could generate actionable insights.

If fact-checks are expected to move mass attitudes as they do in the present paper, fact-checking organizations will have to market themselves more successfully, including but not limited to those who consume misinformation. Thus, our evidence redoubles the onus on news organizations and social media platforms to perform a more effective role in this dynamic—by more visibly, consistently, and definitively fact-checking statements that are empirically and demonstrably false—even when, and perhaps especially when, those falsehoods are espoused by prominent individuals and elected officials. Finally, our findings should also assuage fears that fact-checks of electoral lies may inadvertently provoke unexpected contrary attitudinal effects, which may have led some entities to be more hesitant or ambivalent in their fact-checking efforts than they would be otherwise.

Findings

Finding 1: Exposure to fact-checks increased confidence in the integrity of the 2020 election (p ≤ .01).

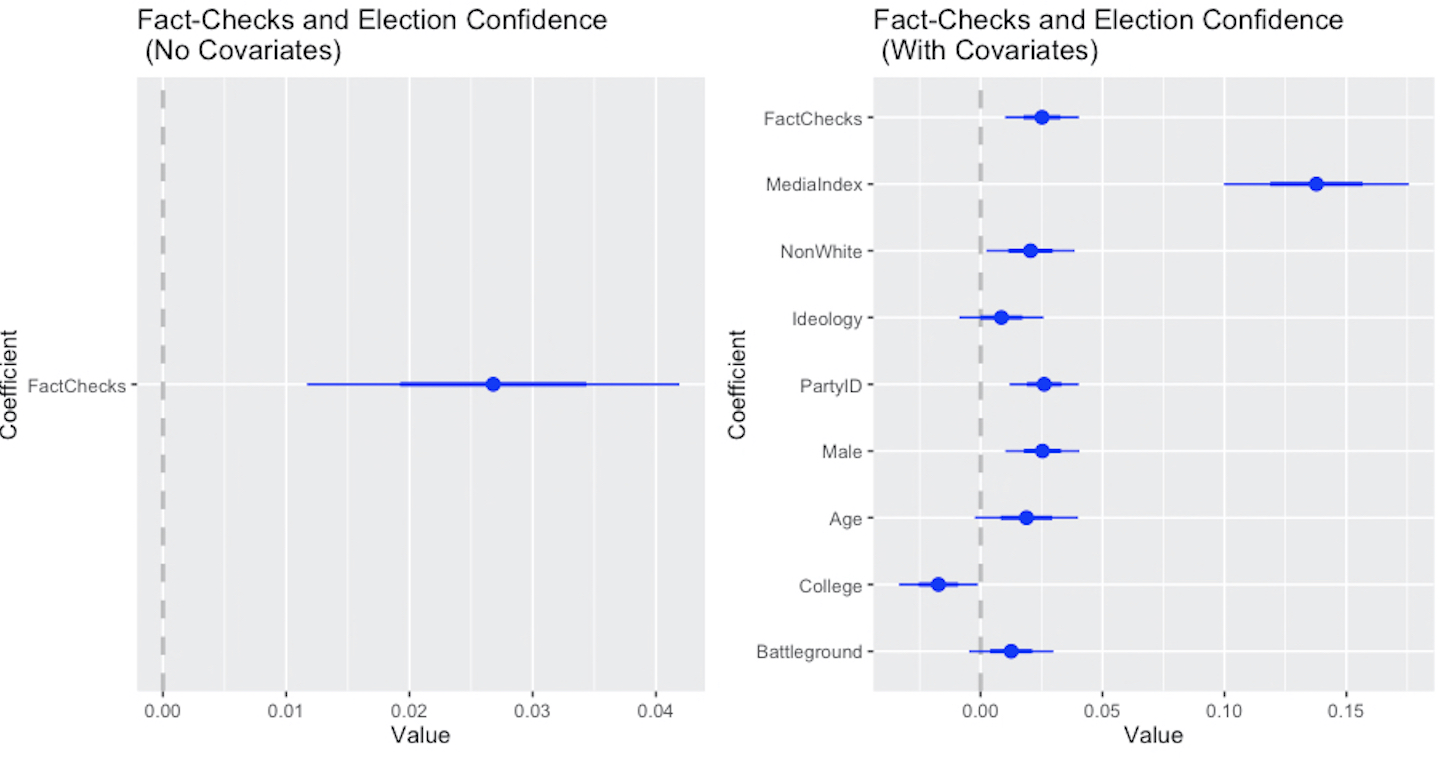

Exposure to fact-checks increased confidence in elections by more than .026 on a 0–1 scale (p ≤ .01). Table A1 in Appendix A presents effects of fact-checks on election confidence.1As specified in our pre-analysis plan, we evaluate the robustness of these results with ordered probit. Please see Table C1 in Appendix C. In Figure 1, we display treatment effects, with and without covariates.

Finding 2: Our findings revealed that partisanship matters (p ≤ .01): the effect of fact-checks on confidence in the integrity of the election differed for Republicans compared to Democrats and Independents.

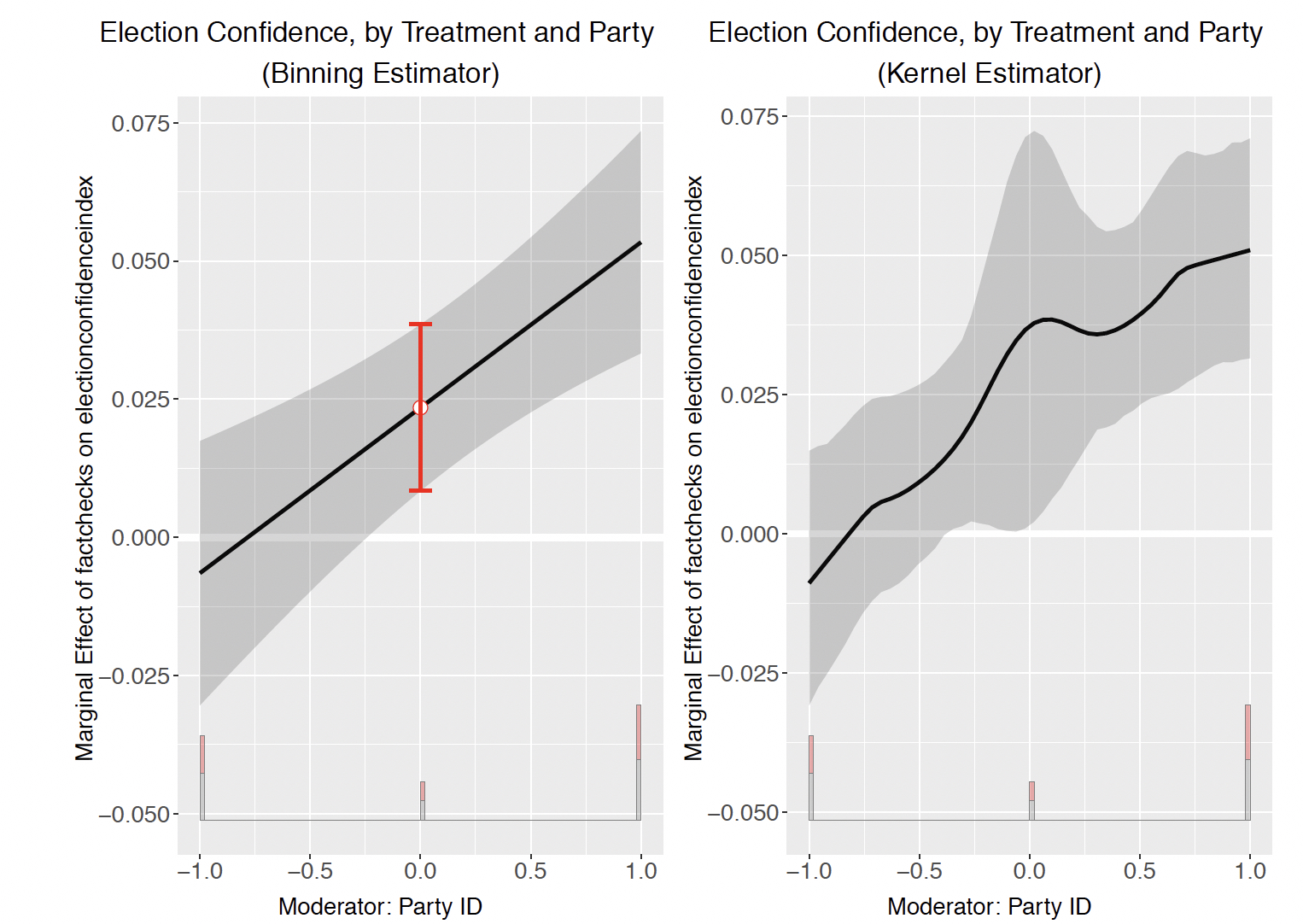

Consistent with previous work substantiating presidents’ influence over the preferences of their co-partisans (Lenz, 2012), as well as Trump’s out-sized influence on his own supporters’ beliefs (Barber & Pope, 2019), our findings reveal a substantial moderating effect of partisanship (p ≤ .01).2Please refer to Table C2 in Appendix C for the results of this analysis. Figure C1 displays box plots of election confidence by party and condition. The estimated average marginal effect of the corrections on election confidence was largest among strong Democrats (β = .06, p ≤ .01) and smaller but still positive and significant among Independents (β = .02, p ≤ .01). However, the effect of these corrections was negligible and non-significant among strong Republicans (β = -.01, p > .1).

To further investigate this interaction, we relied on the binning and kernel estimators offered by Hainmueller, Mummolo, and Xu (2019)3Binning entails splitting the sample into similarly sized groups based on the moderating variable, and then plotting the conditional relationship for each of the groups. Kernel estimators entail estimating a series of local effects utilizing a kernel reweighting approach, which permit more flexible estimates of the marginal effect of the moderator on the dependent variable across the range of values (Hainmueller et al., 2019). to assess the robustness of the interaction effect. These estimators help account for the possibility that there is insufficient coverage for the moderator (in this case, partisanship), and that the linearity assumption may not hold. Figure 2 displays the results. Both approaches corroborated the initial results, and made clear that Democrats and, to a lesser extent, Independents responded to fact-checks by becoming more confident about elections.

Finding 3: We found no evidence that exposure to factual corrections affected voting behavior in terms of either self-reported intention to vote or the validated vote measure.

This null finding seemingly stands in contrast to previous studies, which demonstrated the demobilizing effects of doubts about the integrity of an election (Bailard, 2012; Birch, 2010; Bratton & Van de Walle, 1997; Domínguez, 1998; Hooghe et al., 2011). Taking these previous studies into account, it is not that corrections, in and of themselves, would increase individuals’ propensity to vote, but rather that correcting election falsehoods may increase propensity to vote as a result of restoring confidence in the election.

Accordingly, our analysis investigated whether corrections could undo or counteract the potentially demobilizing effect of false claims that cast doubt on electoral integrity. Following our pre-analysis plan led us to answer the research question on the relationship between fact-checking and voting behavior with a firm negative. However, additional investigation of the data reveals vagaries to this measure that suggest that further inquiry may be prudent. Specifically, our pre-registered analytic strategy neglected to account for the presence of social desirability bias, in which some participants reported having already voted and were thus excluded from the behavioral analysis, but who were subsequently identified as non-voters by the TargetSmart data. We discuss this matter further in Appendix A in the supplementary material.

Methods

We administered the experiment in October 2020 (n = 3,000). The sample was collected by YouGov, a high-quality sample provider compared to its peers (Rivers, 2016).4Please see Table C3 for balance and descriptive statistics. The hypothesis and research questions were pre-registered with the Open Science Framework.5Our pre-registration plan is available at https://osf.io/9g34n. Pre-registration plans are documents in which researchers describe their statistical analysis plans before beginning primary analysis. We posted our plan on a public repository so it could be evaluated by other researchers. The results of analyses of the additional research questions specified in our pre-registration plan, which are largely null, can be found in Appendix D. Prior to treatment assignment, all participants answered questions about their level of political interest and participation, political efficacy, political partisanship, use of news sources, and their level of interest in the 2020 election.6Partisanship was measured on a seven-point scale, with possible responses ranging from “Strong Democrat” to “Strong Republican.” For ease of exposition, we separate respondents into three bins: Democrats, Republicans, and Independents.

Participants were then randomly assigned either to a control or treatment condition. We chose a pure control condition because of concerns about the arbitrariness of placebo selection procedures in many survey experiments. Recent research shows that, in some cases, placebo selection can actually affect treatment effect estimates (Porter & Velez, 2022). In the treatment condition, participants saw six fact-checks7We determined six fact-checks to be a reasonable balance between competing considerations. On the one hand, motivated by previous research demonstrating limited effects on downstream attitudes, our intention was to test the effects of a relatively strong dosage. However, on the other hand, we were also cognizant of the potential for attrition to create issues for the analysis. produced by PolitiFact. PolitiFact is a signatory to the Code of Principles of the International Fact-Checking Networking (IFCN), which commits them to non-partisan fact-checking (IFCN, 2022). All the fact-checks targeted false claims Trump had made that impugned the integrity of the 2020 election. The fact-checks appeared in exactly the same form as they originally appeared.8Appendix B displays a screenshot of the top portion of fact-check webpages as they appeared to participants. To maximize realism (Aronson et al., 1998), the fact-checks were presented in their original format, with the original websites appearing in respondents’ browsers. The fact-checks were imported directly from the PolitiFact website, meaning that there were no differences between the stimuli and the fact-checks on the site. Importantly, this means that the fact-checks repeated the underlying misinformation before refuting the misinformation with countervailing evidence.9The corresponding URLs of all tested fact-checks can be found in Appendix B.

The experimental interface required participants to scroll to read the content, as they would have to do outside the experimental context. While participants were prevented from going forward for 30 seconds, they could have chosen not to read the content. However, it is worth noting that each fact-check begins with an “If Your Time is Short” blurb, which succinctly summarizes the primary facts rebutting the misinformation, followed by a longer discussion of the correction. The fact-checks were presented in random order.

After treatment, participants answered outcome questions about their confidence in the elections to test Hypothesis 1, which predicted that exposure to fact-checks correcting false statements by President Trump regarding the integrity of the election will increase confidence in the election. The confidence items were worded as follows:10Possible responses ranged from 1–4, from “Very confident” to “Not at all confident.” As specified in the pre-registration, the election confidence index is calculated by averaging across these seven evaluations, and then rescaling from 0-1.

Thinking about the presidential election this November 2020, how confident, if at all, are you that. . .

- All votes will be counted fairly

- All eligible voters who want to cast a vote will be able to

- Journalists will provide fair coverage of elections

- Election officials will be fair in making sure all people have an equal chance to vote

- People will not be discouraged from voting through intimidation or violence

- The election results will be protected from foreign interference11The items in the election policy index scaled well together (α = .72). Full scale reliability results for this index can be found in Table C4 in Appendix C.

To investigate our research question of whether exposure to fact-checks would affect self-reported intention to vote, participants were asked whether they intended to vote in the 2020 election or if they had already voted (and for those who intended to vote how they planned to vote). To investigate whether exposure would affect actual turnout, we relied on TargetSmart, a data firm that works with YouGov to provide validated vote data for YouGov panelists. TargetSmart can only provide turnout data on participants it successfully matches from the sample to available turnout records.12Any personally-identifying information was gathered and retained by TargetSmart, with the anonymized survey results data only shared with the researchers via linking codes. This means that at no point did the researchers have access to any personally-identifiable information related to the study’s participants. Consistent with our pre-analysis plan, we coded participants whom TargetSmart successfully matched and identified as having voted as a “1,” and those that TargetSmart successfully matched and identified as not having voted or those that TargetSmart did not successfully match as a “0.” This approach precluded us from conditioning on matchability posttreatment (Montgomery et al., 2018).

One possible concern with our analysis is that our treatments caused conservative-leaning respondents to drop out (please see Table C5 in Appendix C). To estimate the sensitivity of our results to differential attrition, we acquired the complete data set of participants from YouGov, including those who dropped from the study. Then, following the advice of Gerber and Green (2012, see Chapter 7), we re-estimated the results of our first hypothesis while weighting for missingness. Specifically, we first generated indicators for missingness; we then used Logit to predict non-missingness by pre-treatment covariates and the treatment; next, we generated weights; and finally, we re-ran the analysis with the accompanying weights. Table C5 presents the results of this exercise.

Statistically and substantively, the observed effects on election confidence results remain unchanged. Nevertheless, although our results hold when accounting for differential attrition, future studies should attempt to minimize attrition. Last but not least, future research should investigate the durability, or lack thereof, of any attitudinal effects generated by corrections. Existing evidence focused on the effects of fact-checks on belief accuracy gives reason to suspect that effects will attenuate (Carey et al., 2022) but not disappear altogether (Porter & Wood, 2021).

Topics

Bibliography

Aronson, E., Wilson, T. D., & Brewer, M. B. (1998). Experimentation in social psychology. In D. T. Gilbert, G. Lindzey, & S. T. Fiske (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 99–142). McGraw-Hill.

Bailard, C. S. (2012). A field experiment on the internet’s effect in an African election: Savvier citizens, disaffected voters, or both? Journal of Communication, 62(2), 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01632.x

Barber, M., & Pope, J. C. (2018). Does party Trump ideology? Disentangling party and ideology in America. American Political Science Review, 113(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055418000795

Belli, R. F., Traugott, M. W., & Beckmann, M. N. (2001). What leads to voting overreports? Contrasts of overreporters to validated voters and admitted nonvoters in the American National Election Studies. Journal of Official Statistics, 17(4), 479–498.

Berlinski, N., Doyle, M., Guess, A. M., Levy, G., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2021). The effects of unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud on confidence in elections. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2021.18

Birch, S. (2010). Perceptions of electoral fairness and voter turnout. Comparative Political Studies, 43(12), 1601–1622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414010374021

Bisgaard, M. (2019). How getting the facts right can fuel partisan-motivated reasoning. American Journal of Political Science, 63(4), 824–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12432

Bratton, M., & Van de Walle, N. (1997). Democratic experiments in Africa: Regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Carey, J., Guess, A. M., Loewen, P. J., Merkley, E., Nyhan, B., Phillips, J. B., & Reifler, J. (2022). The ephemeral effects of fact-checks on COVID-19 misperceptions in the United States, Great Britain and Canada. Nature Human Behaviour, 6, 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01278-3

Chan, M. S., Jones, C. R., Hall Jamieson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2017). Debunking: A meta-analysis of the psychological efficacy of messages countering misinformation. Psychological Science, 28(11), 1531–1546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617714579

Coppock, A. (2021). Visualize as you randomize. In J. Druckman & D. P. Green (Eds.), Advances in experimental political science (pp. 320–336). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108777919.022

Ferrín, M., & Kriesi, H. (Eds.). (2016). How Europeans view and evaluate democracy. Oxford University Press.

Gerber, A., & Green, D. P. (2012). Field experiments: Design, analysis, and interpretation. Cambridge University Press.

Graves, L. (2016). Deciding what’s true: The rise of political fact-checking in American journalism. Columbia University Press.

Guess, A., & Coppock, A. (2020). Does counter-attitudinal information cause backlash? Results from three large survey experiments. British Journal of Political Science, 50(4), 1497–1515. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123418000327

Guess, A. M., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2020). Exposure to untrustworthy websites in the 2016 US election. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0833-x

Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J., & Xu, Y. (2019). How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Political Analysis, 27(2), 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.46

Hooghe, M., Marien, S., & Pauwels, T. (2011). Where do distrusting voters turn if there is no viable exit or voice option? The impact of political trust on electoral behaviour in the Belgian regional elections of June 2009 1. Government and Opposition, 46(2), 245–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2010.01338.x

IFCN. (2022). Verified signatories of the IFCN Code of Principles. Retrieved September 28, 2022, from https://www.ifcncodeofprinciples.poynter.org/signatories

Lenz, G. S. (2012). Follow the leader? How voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. University of Chicago Press.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

Mernyk, J. S., Pink, S. L., Druckman, J. N., & Willer, R. (2022). Correcting inaccurate metaperceptions reduces Americans’ support for partisan violence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(16). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116851119

Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., & Torres, M. (2018). How conditioning on posttreatment variables can ruin your experiment and what to do about it. American Journal of Political Science, 62(3), 760–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12357

Norris, P. (2019). Do perceptions of electoral malpractice undermine democratic satisfaction? The US in comparative perspective. International Political Science Review, 40(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512118806783

Norris, P. (2014). Why electoral integrity matters. Cambridge University Press.

Nyhan, B., Porter, E., Reifler, J., & Wood, T. J. (2020). Taking fact-checks literally but not seriously? The effects of journalistic fact-checking on factual beliefs and candidate favorability. Political Behavior, 42(3), 939–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09528-x

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Porter, E., Wood, T. J., & Bahador, B. (2019). Can presidential misinformation on climate change be corrected? Evidence from Internet and phone experiments. Research and Politics, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168019864784

Porter, E., & Wood, T. J. (2022). The global effectiveness of fact-checking: Evidence from simultaneous experiments in Argentina, Nigeria, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(37). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2104235118

Porter, E., Velez, Y., & Wood, T. J. (2022). Factual corrections eliminate false beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines. Public Opinion Quarterly, 86(3), 762–773. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfac034

Porter, E., & Velez, Y. (2022). Placebo selection in survey experiments: An agnostic approach. Political Analysis,30(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2021.16

Presser, S., & Traugott, M. (1992). Little white lies and social science models correlated response errors in a panel study of voting. Public Opinion Quarterly, 56(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1086/2692

Rivers, D. (2016). Pew Research: YouGov consistently outperforms competitors on accuracy. YouGovAmerica. https://today.yougov.com/topics/economy/articles-reports/2016/05/13/pew-research-yougov

Schäfer, T., & Schwarz, M. A. (2019). The meaningfulness of effect sizes in psychological research: Differences between sub-disciplines and the impact of potential biases. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00813

Sides, J., Vavreck, L., & Warshaw, C. (2021). The effect of television advertising in United States elections. American Political Science Review, 116(2), 702–718. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542100112X

Spenkuch, J. L., & Toniatti, D. (2018). Political advertising and election results. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(4), 1981–2036. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy010

Thorson, E. (2016). Belief echoes: The persistent effects of corrected misinformation. Political Communication, 33(3), 460–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.(2015).1102187

Wood, T. J., & Porter, E. (2019). The elusive backfire effect. Political Behavior, 41(1), 135–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9443-y

Funding

This research is supported by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation through a grant to the Institute for Data, Democracy & Politics at The George Washington University.

Competing Interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Ethics

This research was deemed exempt by the George Washington University IRB (#NCR202871).

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LARV96

Acknowledgements

We thank Katie Clayton, Matt Graham, and Emily Thorson for comments. YouGov and TargetSmart were responsible for data collection only. All mistakes are our own.