Peer Reviewed

A pro-government disinformation campaign on Indonesian Papua

Article Metrics

1

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

Page Views

This research identifies an Indonesian-language Twitter disinformation campaign posting pro-government materials on Indonesian governance in Papua, site of a protracted ethno-nationalist, pro-independence insurgency. Curiously, the campaign does not employ common disinformation tactics such as hashtag flooding or the posting of clickbait with high engagement potential, nor does it seek to build user profiles that would make the accounts posting this material appear as important participants in a debate over Papua’s status. The campaign simply employs synchronous, duplicate posts by ostensibly distinct authors to ensure that a significant proportion of posts mentioning contentious special autonomy arrangements are pro-government. Despite lacking sophistication, the scale of this information campaign in overall Twitter discussion of special autonomy adds to concerns about the ability of pro-government actors to employ disinformation to constrict political discourse in Southeast Asia.

Research Questions

- What is the nature of accounts posting Indonesian language pro-Indonesian government material on Twitter regarding the Papua independence conflict on social media?

- Is there a relationship between these accounts, suggesting a coordinated campaign or automation?

- What is the content of the posts made by these accounts, and does it reflect contemporaneous Indonesian government messaging on Papua?

Essay Summary

- We assembled a dataset of 1.25 million Indonesian language tweets on Papua posted between 1 December 2018 and 31 May 2021, using 12 search queries covering a range of contemporary events and overarching themes related to the independence conflict.

- We identified a coordinated, automated information campaign posting pro-government Indonesian-language material in support of special autonomy for the two provinces comprising Indonesian Papua. Automation—in the sense of the same entity pre-scheduling multiple ostensibly unrelated accounts to post pro-government material—was evident in time-of-day synchronicity regardless of the date tweets were posted. Within this set of synchronous tweets, we also identified large-scale duplicate posting of identical or near-identical tweets as ostensibly original posts by distinct users.

- The scale of this information campaign is striking, but it eschewed typical mechanisms to influence online debate, such as hashtag flooding, impersonation, or sharing by unconnected users. Its primary intended mechanism to influence Indonesian-language debate on Papua seems to have been simply to post a flood of pro-government information, which makes it hard to know whether the campaign changed minds.

Implications

The online discussion and depiction of the conflict for independence in Indonesia’s easternmost provinces—hereafter the Papua conflict—is a fiercely contested space.1During the period our dataset covers, these provinces were Papua province and West Papua province. In mid-2022, the Indonesian government further divided Papua province to create three additional provinces: South Papua, Central Papua, and the Highlands (DPR, 2022). At times, the Indonesian government has shut down the internet in Papua to obstruct the free flow of information (IFJ, 2020; Safenet, 2022). Those criticising and scrutinising the Indonesian government frequently face online harassment, and the government has also taken punitive action against some of these figures. Indonesian police sought to arrest human rights activist Veronica Koman in 2019 as a provocateur for her online posts on Papua, for example, with the government scholarship agency also demanding that Koman repay the cost of her study abroad (Wiratraman, 2020).2Koman’s parents’ house in Jakarta was also twice targeted in October 2021, with assailants reportedly placing an incendiary device in the first attack and exploding a bomb in the second (CNN Indonesia, 2021). Previous studies have also identified the use of disinformation tactics to spread pro-government messaging via English and Dutch language posts—in each case presumably oriented to an international audience (Burger, 2020; Strick & Thomas, 2019). To our knowledge, few studies have investigated pro-government disinformation utilising Indonesian language posts. This Indonesian language online space—specifically tweets posted in Indonesian—is the focus of this work.

Special autonomy arrangements for Papua, first granted in 2001, are a focus of contention. Special autonomy is one of two key planks to maintain Indonesian sovereignty in Papua, in combination with repression of the independence movement. Special autonomy legislation provides the territory a majority share of natural resource revenues, establishes a Papuan People’s Council (MRP) with wide-ranging powers of review, and provides for the formation of local political parties and a truth and reconciliation commission, although some of these provisions have not been honoured (Barter & Wangge, 2021; Chauvel & Bhakti 2004; McGibbon, 2004). Special autonomy never enjoyed unanimous support in Papua, and dissatisfaction has only increased over time as key provisions have been abandoned and political elites have enriched themselves via corruption of special autonomy funds. Rejection of special autonomy has become a catchcry of Papuan activists—a cry that central authorities were keen to drown out as the 20-year deadline to renew special autonomy approached in mid-2021.

We identified a coordinated, automated information campaign posting pro-government Indonesian-language material in support of special autonomy for Papua. Although the identity of the accounts posting this material does not indicate any transparent link to the Indonesian government, the campaign is highly consistent with contemporaneous government messaging. We confined our focus to the clearest subset of synchronous, duplicate posts. Our own preliminary analysis and the suspension of user accounts within our dataset by Twitter both indicate that the scale of this disinformation campaign on Papua is much larger. We will explore the full extent of this campaign in a subsequent paper.

The campaign promotes pro-government messaging on special autonomy, but it is unclear how it intended to shape public opinion and engage its audience in liking and sharing its messages. Most of the tweets that form part of the campaign receive almost no engagement; the highest number of engagements for any tweet in the set of synchronised posts we have identified is only 252. Nor does the campaign seek to disrupt critical discussion through spurious use of hashtags that are critical or opposed to Indonesian governance—so-called hashtag flooding. The standout hashtag in the campaign is #papuaindonesia, a formulation that independence activists would be highly unlikely to adopt, and the top 50 hashtags are overwhelmingly the campaign’s own positive statements about special autonomy. This campaign does not primarily harass or attack non-government voices. Some posts in the campaign do, however, seek to discredit prominent critics of the government, but this is an incidental focus. Less than 1% of posts in the campaign criticise activists or the media, although almost 15% do criticise the independence movement.

In general, the architects of the campaign have not created inauthentic accounts that imitate indigenous Papuans, even though doing so would be one way to bolster the coordinated posts’ assertion that Papuans support special autonomy. To the extent that those conducting the campaign were concerned with its impact, it appears the main avenue of influence was to ensure that a significant proportion of Twitter posts on special autonomy were pro-government in the lead-up to the July 2021 decision on the policy’s future. In this sense, the campaign may be akin to “zone-flooding:” posting so much information on a contentious issue that only the most committed readers will come to a firm view on the truth of the matter (Illing, 2020).3We thank the second anonymous reviewer for suggesting this conceptualisation.

Studies of disinformation outside of Europe and North America remain comparatively rare (Uyheng & Carley, 2020). In Southeast Asia, existing studies chart the development of a disinformation industry in various countries aimed at winning elections and the ability of governments to capitalise upon disinformation to control political discourse as part of a broader phenomenon of digital authoritarianism (Masduki, 2022; Ong & Tapsell, 2022; Sinpeng & Tapsell, 2021). Drawing on research in the Philippines and Indonesia, Ong and Tapsell (2022) propose a typology of dominant disinformation “work models:” a state-sponsored model combining the repressive machinery of the state with hyper-partisan trolling; an “in-house” model where disinformation is waged by political staff with experience in dirty-campaigning in elections; an advertising and public relations model, where disinformation is outsourced to consultants, and a clickbait model driven by advertising revenue. Other research on disinformation in Indonesia has identified the government as responsible for pro-government information campaigns designed to appear independent of it (Mufti & Rasidi, 2021; Sastramidjaja et al., 2021). Similar to Ong and Tapsell’s outsourced work model, these researchers describe a fluid organisational model assembled for each disinformation campaign, where individuals for hire control multiple fake Twitter accounts, and accounts are automated to post or retweet the campaign’s contents (Wijayanto & Berenschot, 2021). We cannot definitively state that the Indonesian government is responsible for this pro-government campaign on Papua or categorically say how it was organised, as our research solely employs Twitter data. That said, a model of disinformation in which the propagation of a pro-government line was outsourced may account for the lack of sophistication we observe in the campaign. The campaign did not exhibit some common features of disinformation campaigns globally, for example. Nor did it paraphrase duplicate tweets to the extent that a simple similarity test could no longer detect them. It also exhibits stark synchronicity in the time-of-day tweets were posted, including an abrupt midstream shift in the timing of posts coinciding with the start of the Islamic fasting month, Ramadan. In their analysis of a disinformation campaign run by the South Korean secret service during the 2012 presidential election in South Korea, Keller et al. (2020) describe the potential of “satisficing” behaviour on the part of the agents tasked with waging the campaign: “creating just enough low-quality accounts and messages” to meet the requirements of those engaging them (p. 261). Such “satisficing” may also affect the principals engaging these agents, Keller et al. observe, owing to the difficulties of supervision. A similar “satisficing” phenomenon could explain the very visible features of the campaign we describe, which, once detected, clearly mark it as inauthentic.

Nevertheless, the scale of this campaign, when coupled with restrictions on genuinely independent reportage on Papua (Sarmento & Mambor, 2020), demonstrates the ability of pro-government actors to employ social media disinformation to constrict democratic discourse.

Beyond such implications for governance, the relatively distinctive modes of disinformation we examine in this paper remind us that not all disinformation campaigns deploy accounts with many followers to make high-engagement social media posts, and new insights can be generated from the study of myriad forms of disinformation operations. We hope the patterns we set out here will contribute modestly to the detection and fuller understanding of other disinformation campaigns in Indonesia and beyond.

Findings

Finding 1: Tweets on special autonomy differ systematically in key attributes from other tweets in our dataset.

We used the Twitter API v2 for Academic Research to capture all tweets in Indonesian language containing one of 12 keywords or key phrases in certain relevant periods of time (see Table 3 in the Methods section). These 12 search terms were selected to cover the full spectrum of political positions on the status of Papua. The special autonomy search query exhibited extreme values in most of the summary statistics presented in Table 1. Each distinct user posting on special autonomy posts, on average, almost triple the number of tweets on this topic (7.2 tweets per author), compared to distinct authors posting on the next highest search term. The percentage of tweets that are not retweets mentioning special autonomy is, at 56%, by far the highest of any of the search terms, as is the percentage of tweets that contained images, at 46%. However, most of these original tweets receive little to no interaction, with 73% receiving no engagement at all, and much lower engagement compared to most other search terms with an average of 1.6 engagements per tweet.

In summary, compared to authors in our dataset posting on the other search terms, authors who tweet on special autonomy are, on average, very active, often attach images to their tweets, and tweet original content more often than they retweet; however, their tweets receive little to no engagement compared to the other search terms in our dataset.

| Topic of Twitter query | # of tweets | # of distinct authors | Mean tweets per author | % of original tweets | Mean engage- ment per tweet | % of original tweets with zero engage- ment | % of tweets that contain images |

| #Papuanlivesmatter | 152,545 | 80,637 | 1.9 | 12% | 3.6 | 32% | 14% |

| Repayment of scholarship by activist Veronica Koman | 1,444 | 1,125 | 1.3 | 13% | 4.8 | 38% | 6% |

| Killing of State Intelligence Agency representative in Papua | 920 | 879 | 1.0 | 14% | 6.6 | 58% | 9% |

| Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI) | 9,006 | 5,163 | 1.7 | 36% | 2.8 | 74% | 27% |

| Description of independence movement as “terrorists” or “armed criminal group” | 6,829 | 4,810 | 1.4 | 29% | 3.4 | 68% | 9% |

| UN General Assembly | 838 | 448 | 1.9 | 27% | 3.3 | 25% | 23% |

| United Liberation Movement for West Papua or its leader, Benny Wenda | 122,147 | 49,131 | 2.5 | 18% | 3.6 | 55% | 7% |

| #FaktadiPapua (the Facts in Papua) | 1,484 | 976 | 1.5 | 29% | 4.3 | 74% | 28% |

| Nduga killings and counter-insurgency response | 137,301 | 64,379 | 2.1 | 20% | 3.1 | 68% | 6% |

| Special autonomy (otsus) | 275,034 | 38,366 | 7.2 | 56% | 1.6 | 73% | 46% |

| Racism | 600,084 | 263,504 | 2.3 | 9% | 4.1 | 54% | 5% |

| Murder of Christian Pastor Yeremia Zanambani | 9,767 | 5,921 | 1.6 | 11% | 3.9 | 36% | 11% |

| Overall | 1,256,815 | 360,897 | 3.5 | 22% | 3.4 | 65% | 16% |

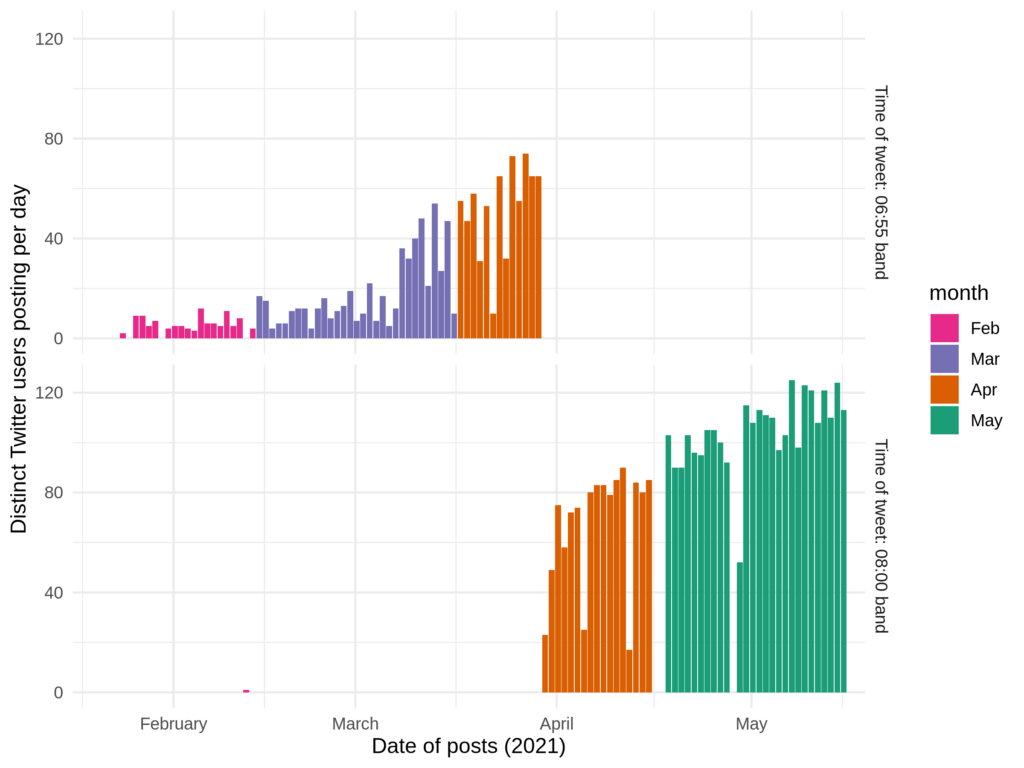

Finding 2: A heavily disproportionate number of tweets in the dataset were posted in the minute starting 6:55 am, and then from mid-April 2021 onwards, in the minute starting 8:00 am Jakarta time. If we consider that nearly all these tweets mention special autonomy, and most received little or no engagement from other users, coordinated automated posting is the only plausible explanation.

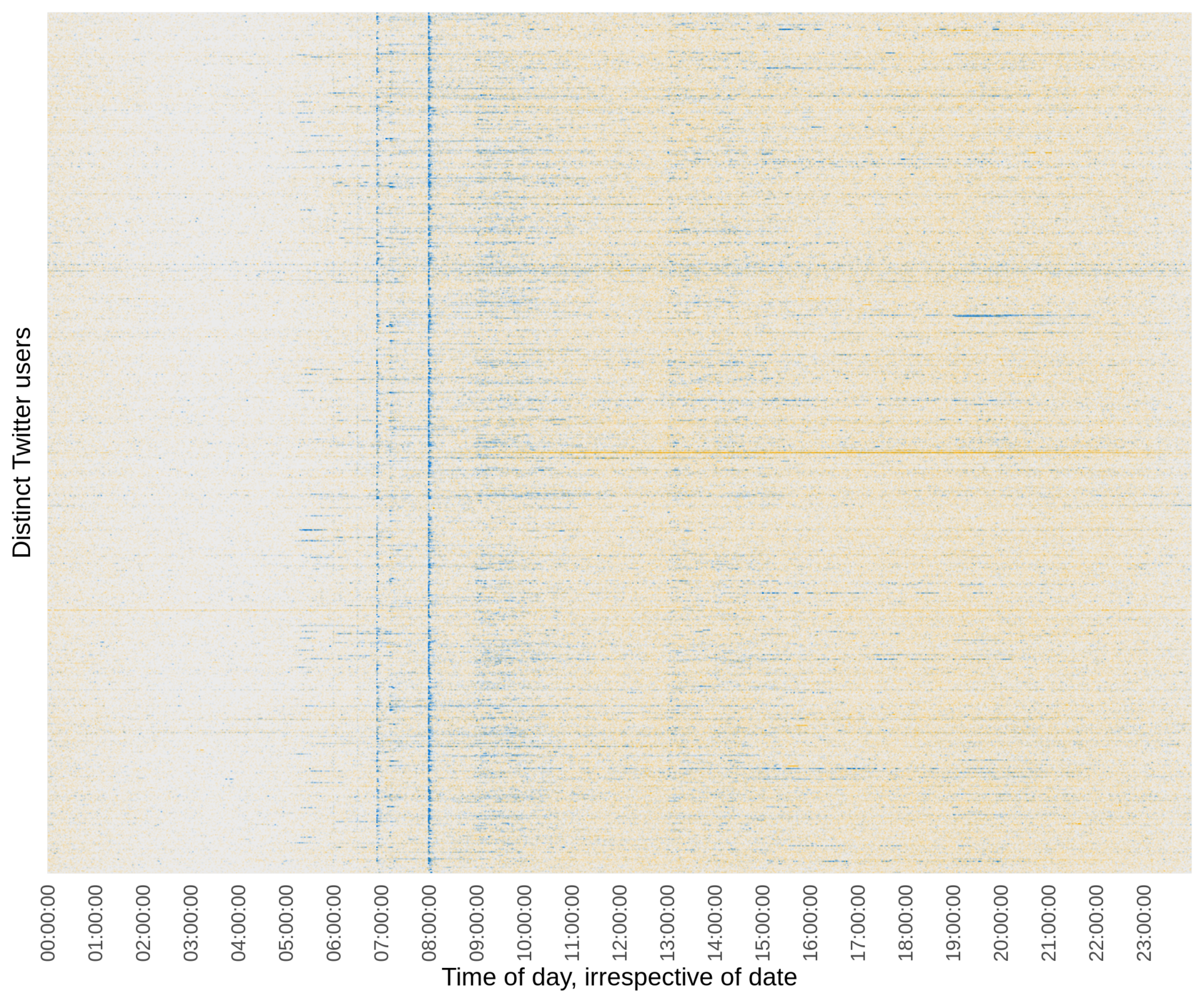

These two minutes account for 1.9% of all tweets in our dataset, representing by far the highest concentration of tweets at any minute of the day.4Although we focus on these two minutes in this paper, the information campaign we discuss is unlikely to be neatly bounded just in these minutes. In particular, the several minutes immediately following 6:55 am and 8:00 am exhibit the next few highest concentrations of tweets in the dataset, and the minute starting 8:01:00 am, in particular, has similarly high concentrations of original tweets on special autonomy. We would expect just 0.14% of tweets to be posted in any two minutes of the day in the somewhat artificial scenario of a random distribution. For tweets mentioning special autonomy, this concentration is even more stark. Remarkably, 8.2% of all tweets mentioning special autonomy were posted in just these two minutes, or in other words, 94.7% of tweets sent in these two minutes mention special autonomy. Figure 1 demonstrates the association with special autonomy: the vertical bands representing the concentration of tweets in these two minutes disappear if tweets mentioning special autonomy are removed from the dataset. The vertical bands are similarly invisible if we filter out tweets that receive no engagement at all (not pictured). This negative association with engagement eliminates the clearest alternative explanation for this temporal concentration of tweets, namely that users post more tweets during these minutes as they are opportune moments to maximise the tweets’ visibility.

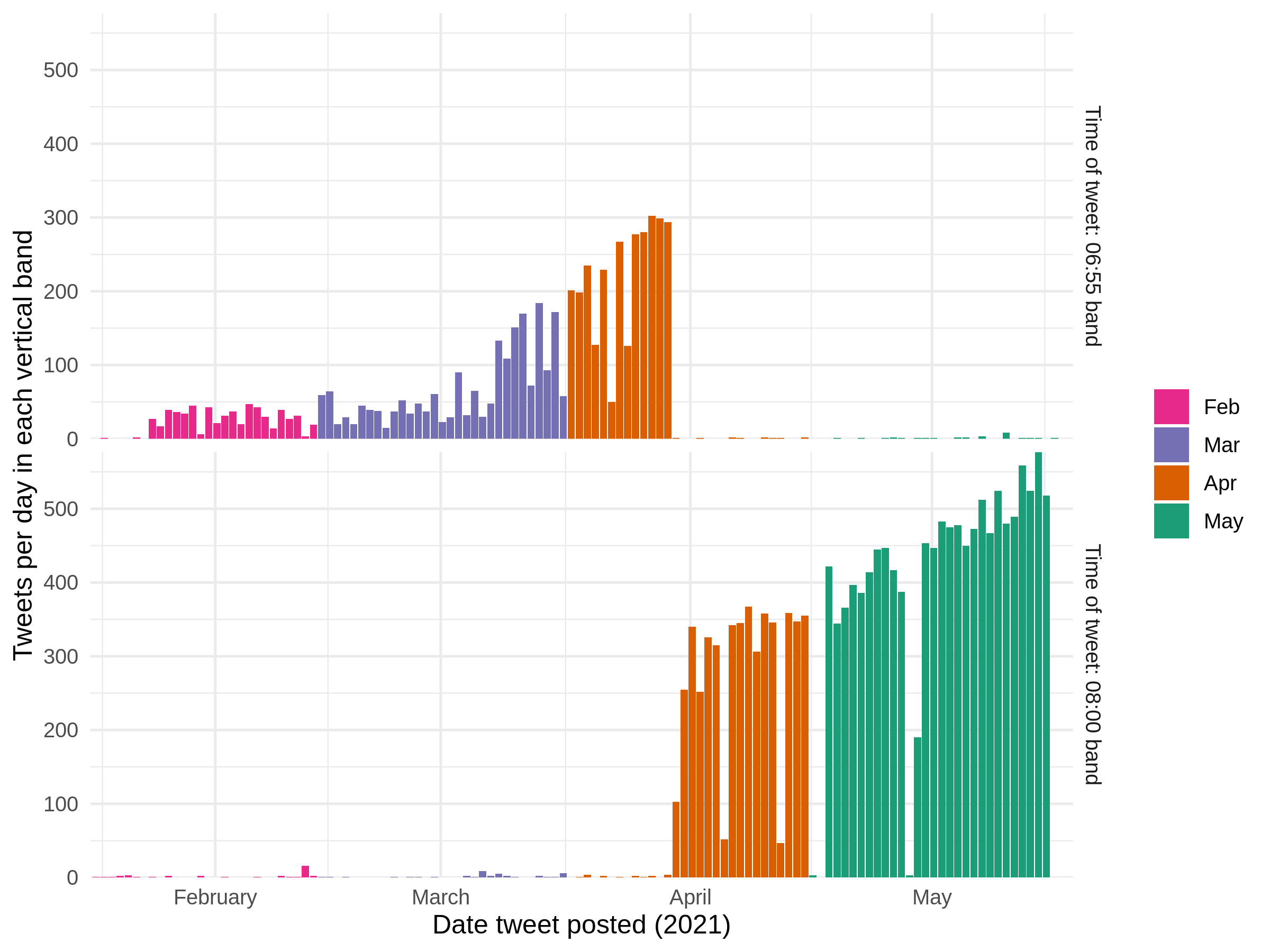

Examination of the dates on which users posted the tweets in the two blue vertical bands in Figure 1 underlines our conclusion that coordinated, automated posting—whereby accounts are pre-scheduled to synchronously post pro-government material—is thus the only plausible explanation for this pattern of posts. Prior to 13 April 2021, almost all these tweets were posted in the minute starting 6:55 am. On 13 April, their timing abruptly shifts to the minute starting 8:00 am (Figure 2). This shift coincides with the beginning of the Islamic fasting month, Ramadan (Aida, 2021), and may thus reflect changed expectations about the time at which Indonesian social media users would be checking their Twitter feeds. We have not identified any time zone shift that coincides exactly with this change, which in any case is not an exact multiple of an hour.5Morocco and Mali shift time zone the closest to this change, on 11 April 2021, but their time zone change is in the opposite direction, with clocks turned back one hour. See “Daylight savings time” (2021). Although the accounts posting these tweets are ostensibly distinct, this pattern is highly suggestive that they are all being directed by a single entity.

Finding 3: These synchronous tweets on special autonomy share an additional characteristic: most are duplicates or near duplicates of each other. At face value, 22,479 of the 23,853 tweets in the vertical bands are original tweets about special autonomy, posted by 2,668 different authors. In reality, just 760 of these tweets are unique (3.4%) as measured by a Jaccard similarity test (Jaccard, 1912).6Note: Once URLs are removed (which Twitter generates uniquely even when linking to the same webpage). The Jaccard similarity test uses a threshold of 0.69. See Methods section for further details. The remainder are duplicates or near duplicates of just 1,329 distinct tweets.

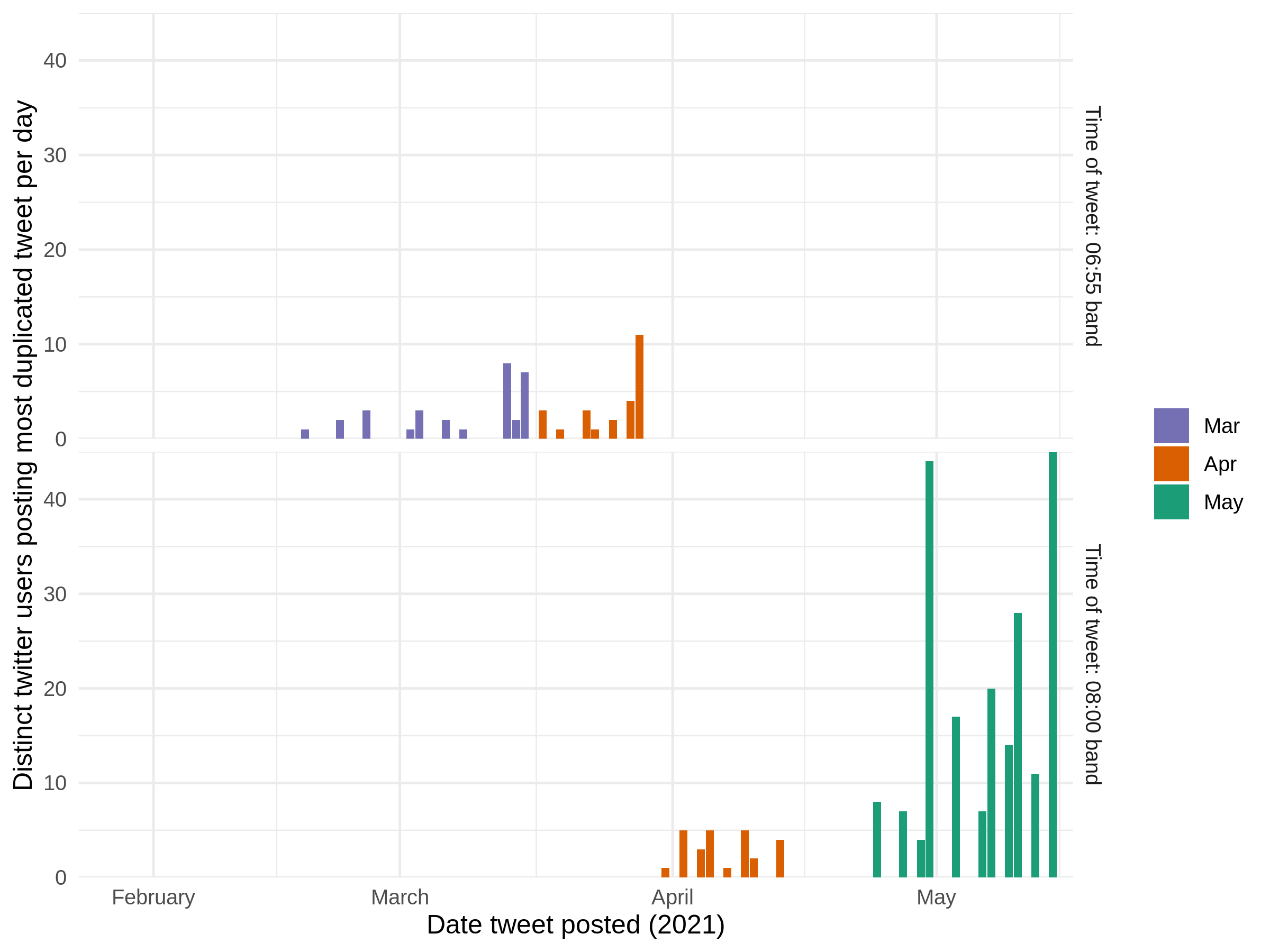

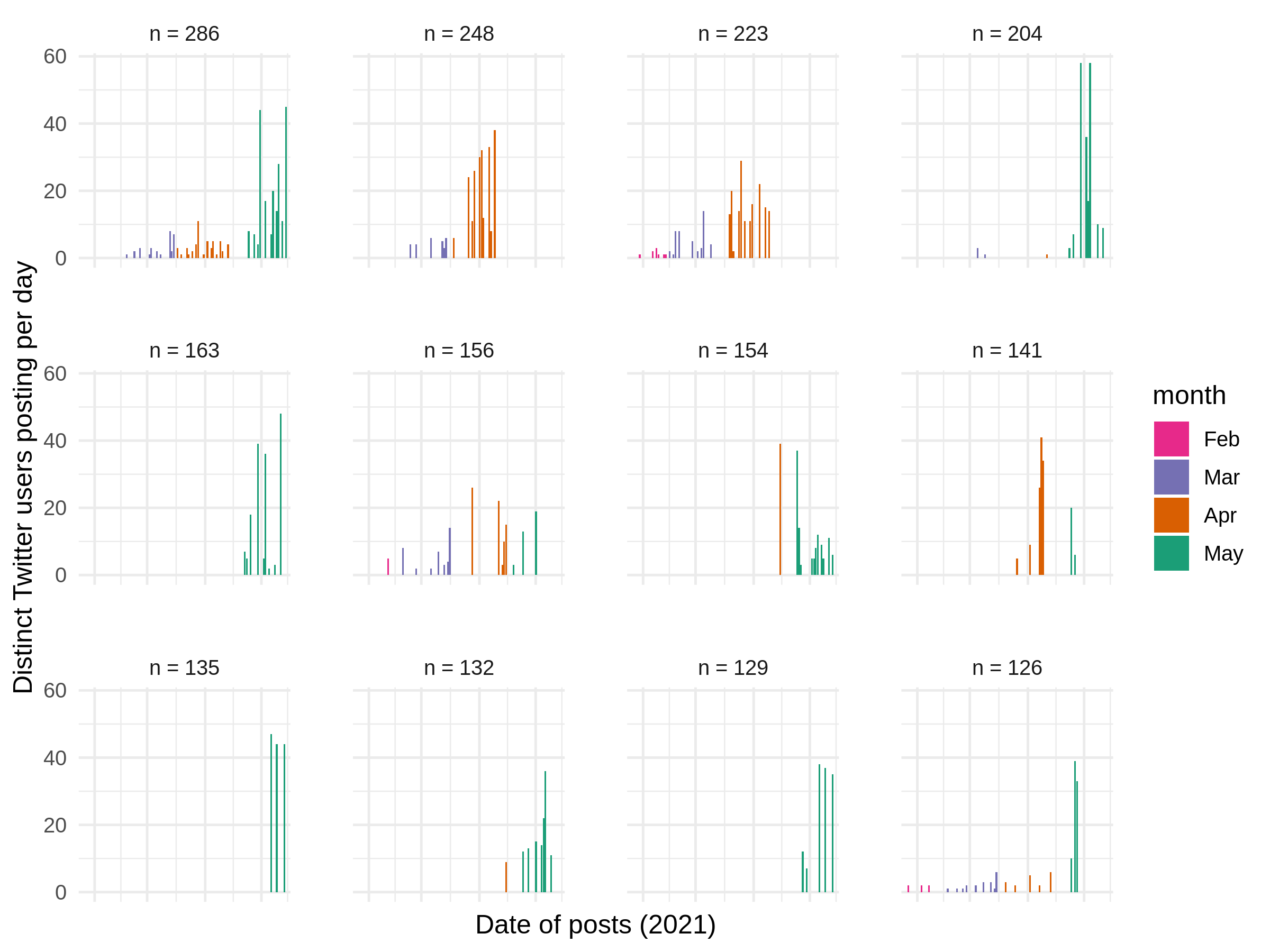

The most duplicated tweet appears 286 times, posted by 246 distinct authors, and declares that special autonomy demonstrates the seriousness of the Indonesian government in improving welfare in Papua. Twitter users posted this tweet over the course of three months in 2021, although it appears in increasing numbers in May (Figure 3). This distribution is broadly typical of the most duplicated tweets. Figure 4 reveals many of these tweets similarly were posted recurrently over the course of 2021.

Posting one of 286 duplicates of a tweet in the same two minutes of the day is highly suggestive that these 246 ostensibly distinct authors are, in fact, closely coordinated. Examination of all 5,343 original tweets these 246 accounts posted in the blue vertical bands shown in Figure 1 (23.4% of all original tweets in these bands) provides further evidence of coordination: these accounts are synchronous both in the time of day and the dates on which they post these tweets (see Figure 5). They are almost certainly automated accounts managed by the same entity, which has pre-scheduled them for synchronous, duplicative use.

Finding 4: Duplicates or near duplicates of just these 1,329 tweets posted in the minute starting 6:55 am and the minute starting 8:00 am Jakarta time make up 14.0% of all original tweets mentioning special autonomy over the 2.5 years of our dataset, and 7.9% of all tweets on special autonomy including retweets.7We scraped tweets on special autonomy using its ubiquitous Indonesian language contraction otsus (a contraction of otonomi [autonomy] and khusus [special]). Although it is possible the percentages cited above may differ if we had also searched using otonomi khusus, we have no reason to believe this would be the case.

Both the scale and the lack of variety of this information campaign are remarkable. Moreover, duplicates of the 1,329 tweets would comprise an even higher percentage of all tweets on special autonomy if we included posts made outside of these two time bands. For example, the most duplicated tweet in the vertical bands—appearing 286 times—appears with similar wording a total of 445 times in the entire dataset, including tweets outside of the two minutes in question.

Finding 5: The content of tweets in the vertical bands is closely aligned with contemporaneous Indonesian government messaging on the Papua conflict. Two-thirds of these tweets praise Indonesian government policy, including the staging for the first time of Indonesia’s National Games (PON) in Papua in 2021. A substantial proportion of tweets—around 17%—also either quote indigenous Papuans expressing pro-government positions or assert that indigenous Papuans support special autonomy.

A core feature of the Indonesian government’s approach to the Papua conflict has been to disavow any political dimension to Papuan contestation of Indonesian sovereignty, and instead claim that Papuan disaffection reflects economic hardship (ICG, 2010). Accordingly, many of the tweets praising special autonomy and government policy—half of all tweets in the vertical bands—highlight the economic dividends for Papuans of special autonomy and other Indonesian government policies. Mentions recur of scholarships for indigenous Papuans to study abroad, recruitment of Papuans into state institutions, infrastructure development, as well as praise of the Jokowi government’s “sea toll” policy of subsidising shipping to outer islands. Other tweets in this category assert that dividing Papua into more provinces and districts (pemekaran) will deliver economic benefits to Papuans. The creation of new provinces is contentious, as many Papuans see such divisions as intended to prevent the emergence of a united Papuan political bloc that could secede from Indonesia (ICG, 2003). The 2021 amendment to special autonomy legislation removed the need for the central government to consult with Papuan institutions on the creation of new provinces, triggering legal challenges and protests from within Papua (Costa, 2022; IPAC, 2021). In June 2022, the Indonesian national legislature passed laws to create three new Papuan provinces: Central Papua, South Papua, and the Highlands (DPR, 2022).

| Topics | Statement | Statement by official | Statement by indigenous Papuan | Total |

| Praise of special autonomy or government policy | 40.6% | 4.3% | 5.9% | 50.9% |

| Positive mention of staging of National Games (PON) in Papua | 12.4% | 3.0% | 0.5% | 16.0% |

| Criticism of independence movement | 8.1% | 4.1% | 2.1% | 14.4% |

| Assertion that indigenous Papuans support special autonomy | 7.2% | N/A | N/A | 7.2% |

| Covid-19 pandemic | 3.3% | N/A | N/A | 3.3% |

| Criticism of Papuan governance | 1.5% | 0.4% | 1.0% | 2.9% |

| Criticism of activists or media reportage | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.4% | 0.7% |

| Criticism of special autonomy or Indonesian governance in Papua | 0.6% | N/A | N/A | 0.6% |

| Other | 4.1% | N/A | N/A | 4.1% |

The then forthcoming staging of Indonesia’s National Games (PON) in Papua in October 2021 so frequently receives positive mention that it merits its own category distinct from other government programs. Staging the games in Papua carried a clear diplomatic dimension to assert that the territory was a normal, uncontested part of Indonesia.8See Inkiriwang (2021) for an example of an Indonesian observer making this point. Attendant to this goal, numerous tweets emphasise that venues are secure and that the armed wing of the independence movement does not operate in urban areas.

Many tweets criticising the independence movement focus on incidents of violence attributed to their armed wing, notably the fatal shooting of two schoolteachers by the West Papuan Liberation Army (TPNPB) in Beoga District in April 2021 (“Jenazah dua guru,” 2021). Various tweets report condemnation by church figures and a human rights activist of the shooting or assert more broadly that the independence movement has no concern for education. Following the death in a shootout of the Papuan head of the state intelligence agency in April 2021, which prompted the Indonesian government to designate the Free Papua Organisation (OPM) as terrorists, other tweets present the agreement of various Islamic organisations and societal figures with this nomenclature.

Across each of the categories is a common concern to put pro-government messaging in the words of indigenous Papuans or, more generally, to assert that indigenous Papuans support special autonomy. Approximately 17% of tweets fall into this category. Many of the indigenous Papuans cited as supporting special autonomy are of “second tier” prominence, for example, being societal figures of local rather than provincial standing. Also aimed at confining discussion of Papua to specific indigenous Papuan voices, other posts seek to delegitimise Indonesian human rights lawyer Veronica Koman as a non-Papuan located in Australia. Koman emerged in 2019 as a prominent critic of Indonesian governance in Papua, posting numerous videos of protests and violence in Papua on social media. Some of these tweets quote Nick S. Messet, describing him as a founder of the OPM, as saying Koman has no right to speak on behalf of Papuans. In fact, Messet has long since switched sides and become a spokesperson and lobbyist for Indonesian governance in Papua (Chauvel, 2009; Farneubun, 2019). A second thematically related set of tweets implicitly acknowledge that indigenous Papuans do not universally support special autonomy but asserts that they would if Papuan governance improved.

In their taxonomy of disinformation, Kapantai et al. (2019) propose that the contents of “biased or one-sided” posts should be “mostly false” (as opposed to “mostly true” or just “false”). This definition does not capture what it is about these tweets that makes them disinformation, however. The contents of some of the tweets are demonstrably false, such as criticism in 2021 of Veronica Koman attributed to a former OPM member who died in 2017 (“Berpotensi Hoax,” 2021). Others make dubious but essentially unverifiable statements, such as claims of Papuan support for various Indonesian government policies or claims of the economic benefits of creating new districts and provinces. But many others are factual statements of elements of Indonesian government policy on Papua, albeit combined with a contested statement that these details show that special autonomy should continue. Instead, it is the notion that these tweets are spontaneous posts by authentic Twitter users that is false, and which marks the campaign as disinformation.9C.f. Keller et al. (2020, p. 259).

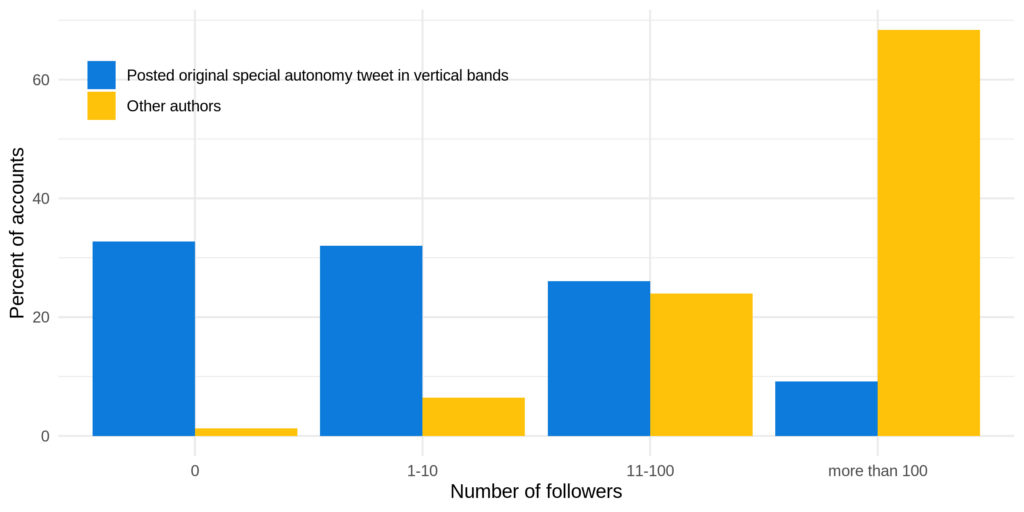

Finding 6: In aggregate, the accounts that post in the vertical bands about special autonomy are newer, have fewer followers, and are more likely to be effectively anonymous compared to the overall cohort of Twitter users tweeting about Papua. More than half (58%) have been suspended since we assembled our dataset for reasons we do not know. Very few of these accounts present themselves as indigenous Papuans, curiously at odds with the campaign’s focus on asserting that indigenous Papuans support special autonomy.

The contrast is clearest if we focus on accounts posting original tweets on special autonomy within the vertical bands, where this information campaign is concentrated. Most of these accounts have almost no followers: their median number of followers is just three compared to 237 for the rest of the dataset (Figure 6). The median date for account creation for this subset of accounts falls on 28 March 2021; 99.1% of accounts in the whole dataset had been created by that time.

Half of the accounts (50.9%) posting original tweets about special autonomy in the vertical bands had a blank author description, compared to just 18.9% of accounts in the entire dataset. Examination of a random selection of 100 of these accounts also revealed only 32% had profile pictures featuring an identifiable person. Many of these pictures were unlikely to be the account holder—a number appeared to be Korean youths, and some were pictures of young children, for example. Among the sample, only one account clearly identified itself as indigenous Papuan, under the username leniskagoya. The account uses a photo of presidential advisor Lenis Kogoya, but the account may not be authentic. Although it posts as Lenis Kogoya (note the variance in spelling with the account username), it has a blank author description, and we were not able to find any mention of Lenis Kogoya having a Twitter account. Nor do other accounts mention the leniskagoya account when discussing Lenis Kogoya on Twitter. The account also has fewer than 1000 followers, suspiciously low for an Indonesian presidential advisor. Contrast these features with the account of another presidential advisor who has worked on Papua policy, Jaleswari Pramodhawardani. Her Twitter account describes her explicitly as a presidential advisor, is followed by the account of the Presidential Staff Office and the president’s chief of staff, and has approximately 17,000 followers.

Finding 7: The vertical bands are an effective entry point to demonstrate the presence of a large-scale disinformation campaign on special autonomy in Papua, but they do not capture the full scale of the campaign.

As one illustration, as of October 2022, Twitter has suspended 9,438 user accounts (2.6%) in our dataset since we scraped the data in June 2021; these users posted 103,678 of the tweets we scraped (8.2%). A highly disproportionate number of these suspended accounts posted at least one original tweet about special autonomy in the vertical bands (18.1%), further corroborating our conclusions regarding coordinated, inauthentic posting. (Overall, Twitter has suspended 45.9% of accounts that posted at least one tweet in the vertical bands.) Nevertheless, 81.5% of the subsequently suspended accounts in our dataset were not captured by an exclusive focus on the vertical bands, as none of the tweets they posted in our dataset fell during these two minutes of the day. We will explore the posts of these accounts and the links between them in a subsequent paper. Similarly, although a very high proportion of the tweets in the vertical bands are duplicates or near duplicates, in our preliminary analysis, we have identified other clusters of duplicate tweets in the dataset.

Methods

To assemble our dataset of approximately 1.25 million tweets, we used the Twitter API v2 for Academic Research (https://developer.twitter.com/en/products/twitter-api/academic-research) and employed 12 search queries covering a range of contemporary events and overarching themes related to the independence conflict (see Table 3). Although our focus is pro-government disinformation, these search terms include keywords that we anticipated would be associated with the full spectrum of positions on the Papua conflict. Otsus (special autonomy), as discussed, is a key policy to maintain Indonesian sovereignty in Papua. Tweets mentioning autonomy are consequently more likely to be pro-government. Similarly, teroris (terrorist) and KKB (armed criminal group) are each key labels the Indonesian government uses to attempt to discredit armed independence supporters, and so mention of this search term is very likely to indicate a pro-government post. By contrast, #Papuanlivesmatter, a hashtag that emerged in response to the global Black Lives Matter movement and incidents of racism against Papuans, might be expected to yield a greater proportion of tweets critical of the Indonesian governance in Papua.

For search terms based on events, we scraped Twitter starting from the occurrence of the event until the endpoint of our dataset. One such event provided the start point for our dataset: the fatal attack on road workers constructing the Trans-Papua Highway in Nduga district on 2 December 2018 (Wangge & Webb-Gannon, 2020). For search queries covering themes, we scraped Twitter for the entire duration of our dataset, from 1 December 2018 until 31 May 2021.

| Query | Topic of Twitter query | Type | Start | End | # of tweets |

| Papua NKRI | Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI) – a nationalist slogan | theme | 2018-12-01 | 2021-05-31 | 9,006 |

| #FaktadiPapua | The Facts in Papua (FaktadiPapua) hashtag | theme | 2018-12-01 | 2021-05-31 | 1,484 |

| Papua Teroris OR Papua KKB | Description of independence movement as “terrorists” or “armed criminal group” | theme | 2018-12-01 | 2021-05-31 | 6,829 |

| Papua BIN OR Papua Nugraha | Killing of State Intelligence Agency representative in Papua | event | 2021-04-24 | 2021-05-31 | 920 |

| ULMWP OR Wenda | United Liberation Movement for West Papua or its leader, Benny Wenda | theme + event | 2018-12-01 | 2021-05-31 | 122,147 |

| Otsus | Special autonomy (otsus) | theme | 2018-12-01 | 2021-05-31 | 275,034 |

| Nduga | Nduga killings and counter-insurgency response | theme + event | 2018-12-01 | 2021-05-31 | 137,301 |

| Rasisme | Racism | theme | 2018-12-01 | 2021-05-31 | 600,084 |

| #Papuanlivesmatter | Papuanlivesmatter hashtag | theme | 2020-05-01 | 2021-05-31 | 152,545 |

| Sidang Umum PBB Papua OR UNGA Papua OR Vanuatu Papua OR #SidangPBB | Mention of Papua in the UN General Assembly | theme | 2018-12-01 | 2021-05-31 | 838 |

| Beasiswa Veronica Koman | Repayment of scholarship by activist Veronica Koman | event | 2020-08-01 | 2021-05-31 | 1,444 |

| Zanambani | Murder of Christian Pastor Yeremia Zanambani | event | 2020-09-01 | 2021-05-31 | 9,767 |

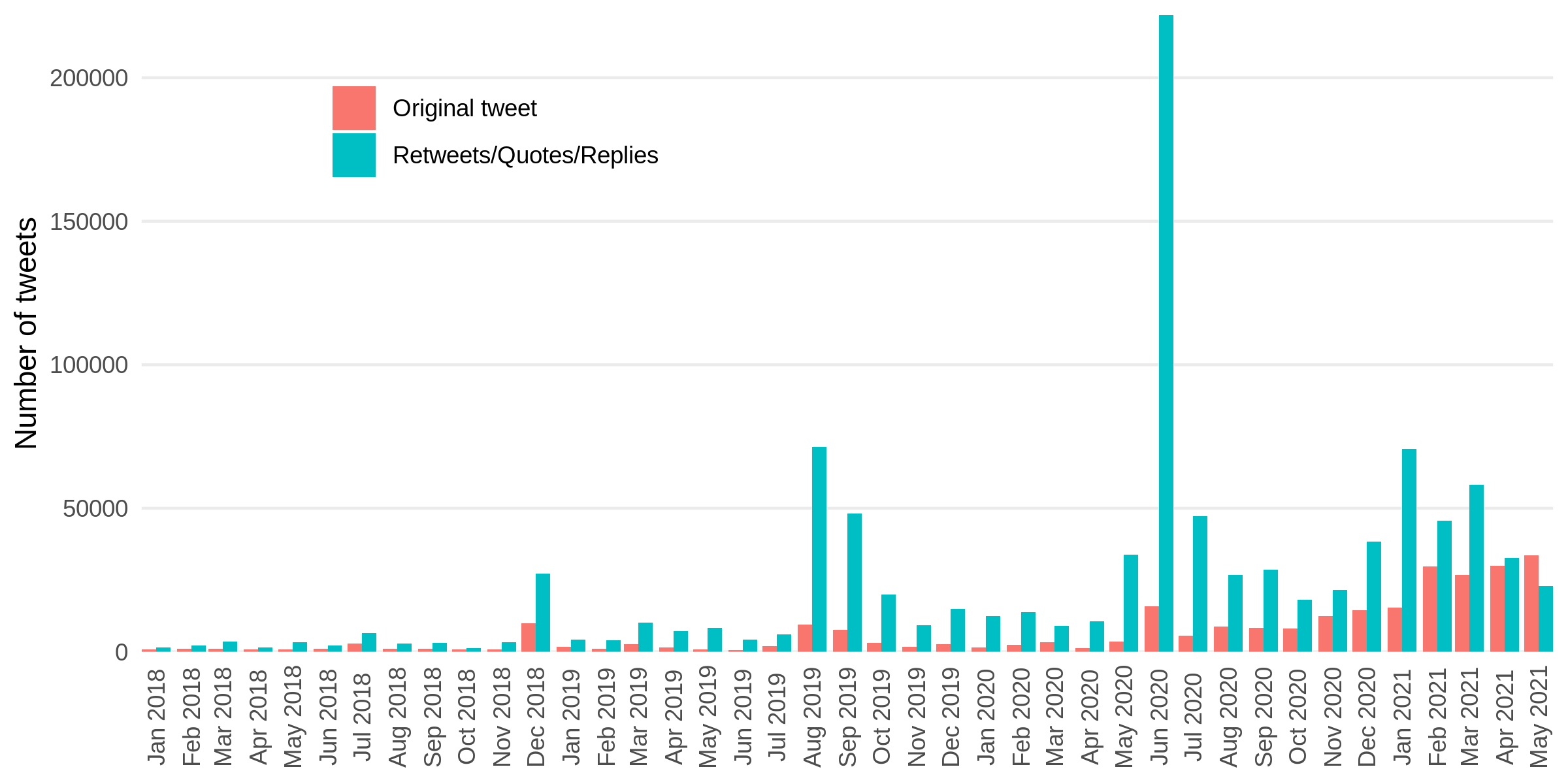

Although our dataset covers 2.5 years, the distribution of tweets over time in the dataset is skewed towards more recent months, especially for original tweets. Half of all tweets were sent on or after 16 June 2020, during the final 11.5 months the dataset covers. This skew to recency is more pronounced for original tweets (i.e., tweets that are not retweets), half of which were sent in the five months on or after 19 December 2020. In part, this time distribution results because some search terms started part-way through the period covered by the dataset. For example, the #Papuanlivesmatter search query captured more than 10% of tweets but began only in May 2020.

The initial scrape using our search queries was performed on 9 June 2021 and yielded almost 1.6 million tweets, after which we filtered the data in three stages to obtain our dataset. First, we removed around 1,500 irrelevant tweets that mentioned an account named similarly to prominent independence activist Benny Wenda. Second, as the scrape for each search query was done separately, we removed approximately 60,000 duplicate tweets which were captured by multiple search terms. (Approximately 5% of the dataset contains more than one keyword, and these tweets would have appeared multiple times without this stage.10Although duplicates were removed prior to language filtering, this figure is calculated based on the final dataset, i.e., after language filtering.) Finally, we filtered to remove tweets that did not contain Indonesian language text, removing approximately a further 275,000 tweets. As manual examination suggested Twitter’s language identification algorithm was not capturing all Indonesian language tweets, we retained any tweet that satisfied at least one of the following conditions: flagged as Indonesian by Twitter, flagged as Indonesian or Malay by the polyglot package for Python (https://github.com/aboSamoor/polyglot), or did not contain any text. These empty tweets were retained in case they included pictures with Indonesian language embedded, a decision also based on manual examination of the dataset.

Duplicate or near duplicate tweets were identified using the Quanteda package for R (Benoit et al., 2018) and its sub-packages. We ran a Jaccard similarity test on tokenised versions of the tweet text (with Twitter-generated URLs and punctuation first removed) using Quanteda’s textstat_simil function. Jaccard similarity scores range from 0 (least similar) to 1 (identical); based on manual examination of a sample of tweets, we identified 0.69 as a threshold for the test, which captured most tweets that appeared as duplicates or near duplicates to a human eye, without capturing tweets that were clearly distinct. We then employed the IGraph package for R to identify components (distinct tweets and their duplicates and near duplicates). Content classifications presented in Table 2 were generated by manual coding of the first tweet in each component.

To examine the identity of accounts posting original tweets about special autonomy, we first determined the median number of posts in the vertical bands by such accounts (three tweets) and then randomly sampled 50 accounts above the median, and 50 below or equal. As the two sets of accounts are similar in the relevant summary statistics, observations based on them are reported as a single random stratified sample in findings.

Analysis code was written using the tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019) and plots were generated using ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016).

Topics

Bibliography

Aida, N. R. (2021, April 12). Resmi, 1 Ramadhan jatuh pada Selasa 13 April 2021, besok mulai puasa [Official, 1 Ramadhan falls on Tuesday 13 April 2021, fasting starts tomorrow]. Kompas.com. https://www.kompas.com/tren/read/2021/04/12/200000865/resmi-1-ramadhan-jatuh-pada-selasa-13-april-2021-besok-mulai-puasa?page=all.

Barter, S. J., & Wangge, H. R. (2022). Indonesian autonomies: Explaining divergent self-government outcomes in Aceh and Papua. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 52(1), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjab009

Benoit, K., Watanabe, K., Wang, H., Nulty, P., Obeng, A., Müller, S., & Matsuo, A. (2018). Quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), 774. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

Berpotensi hoax, AJI kecam pemberitaan tak akurat soal pernyataan OPM Nicholas Youwe [A potential hoax, AJI criticises inaccurate reportage of the statement of OPM member Nicholas Youwe]. (2021, May 11). Suara Papua. https://suarapapua.com/2021/05/11/berpotensi-hoaks-aji-kecam-pemberitaan-tak-akurat-soal-pernyataan-opm-nicholas-youwe/

Burger, P. (2020, November 10). Campagne tegen Papoea-activisten mikt met nepaccounts ook op Nederland [Campaign against Papua activists also aims at the Netherlands with fake accounts]. Nieuwscheckers. https://nieuwscheckers.nl/campagne-tegen-papoea-activisten-mikt-met-nepaccounts-ook-op-nederland/

Chauvel, R. (2009, April 23). Between guns and dialogue: Papua after the exile’s return. APSNet Policy Forum. https://nautilus.org/apsnet/between-guns-and-dialogue-papua-after-the-exiles-return/

Chauvel, R., & Bhakti, I. N. (2004). The Papua conflict: Jakarta’s perceptions and policies. East-West Center. https://www.eastwestcenter.org/publications/papua-conflict-jakarta%E2%80%99s-perceptions-and-policies

CNN Indonesia. (2021, November 11). Orang tua Veronica Koman dikabarkan resah dan ketakutan pasca ledakan [Veronica Koman’s parents reportedly anxious and afraid after explosion]. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20211111070932-12-719501/orang-tua-veronica-koman-dikabarkan-resah-dan-ketakutan-pasca-ledakan

Costa, F. M. L. (2022, March 15). Dua warga tewas tertembak akibat bentrokan tolak pemekaran Papua di Yahukimo [Two people shot dead as a result of clashes at protests in Yakuhimo rejecting division of Papua]. Kompas. https://www.kompas.id/baca/nusantara/2022/03/15/bentrok-tolak-pemekaran-papua-di-yahukimo-dua-warga-tewas-tertembak

Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR). (2022, June 30). DPR sahkan 3 UU provinsi baru, Puan: jaminan hak rakyat Papua dalam pemerataan pembangunan [Parliament passes 3 laws [establishing] new provinces, Puan: a guarantee of the rights of the Papuan people in [the context of] even development]. https://www.dpr.go.id/berita/detail/id/39597/t/DPR+Sahkan+3+UU+Provinsi+Baru%2C+Puan%3A+Jaminan+Hak+Rakyat+Papua+dalam+Pemerataan+Pembangunan

Farneubun, P. K. (2019, August 7). Competing Papuan identities. Inside Indonesia. https://www.insideindonesia.org/competing-papuan-identities

International Crisis Group (ICG). (2003, April 9). Dividing Papua: How not to do it. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/indonesia/dividing-papua-how-not-do-it

International Crisis Group (ICG). (2010, August 3). Indonesia: The deepening impasse in Papua. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/indonesia/indonesia-deepening-impasse-papua

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ). (2020, June 4). Indonesia: Court finds internet ban in Papua and West Papua violates the law. https://www.ifj.org/media-centre/news/detail/category/asia-pacific/article/indonesia-court-finds-internet-ban-in-papua-and-west-papua-violates-the-law.html

Illing, S. (2020, February 6). “Flood the zone with shit”: How misinformation overwhelmed our democracy. Vox. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/1/16/20991816/impeachment-trial-trump-bannon-misinformation

Inkiriwang, F. F. W. (2021, October 6). The 20th PON: Sports and peace in Papua. The Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2021/10/06/the-20th-pon-sports-and-peace-in-papua.html

Institute for Policy Analysis and Conflict (IPAC). (2021, December 23). Diminished autonomy and the risk of new flashpoints in Papua. http://cdn.understandingconflict.org/file/2021/12/Report_74_Papua_Otsus.pdf

Jaccard, P. (1912). The distribution of the flora in the Alpine zone. New Phytologist, 11(2), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1912.tb05611.x

Jenazah dua guru yang ditembak TPNPB di Beoga sudah diterbangkan ke kampung halaman [Bodies of two teachers shot by West Papua National Liberation Army have been flown home]. (2021, April 11). Suara Papua. https://suarapapua.com/2021/04/11/jenazah-dua-guru-yang-ditembak-tpnpb-di-beoga-sudah-diterbangkan-ke-kampung-halaman/

Kapantai, E., Christopoulou, A., Berberidis, C., & Peristeras, V. (2021). A systematic literature review on disinformation: Toward a unified taxonomical framework. New Media & Society, 23(5), 1301–1326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820959296

Keller, F. B., Schoch, D., Stier, S. & Yang, J. (2020). Political astroturfing on Twitter: How to coordinate a disinformation campaign. Political Communication, 37(2), 256–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1661888

Masduki (2022). Cyber-troops, digital attacks, and media freedom in Indonesia. Asian Journal of Communication, 32(3), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2022.2062609

McGibbon, R. (2004). Secessionist challenges in Aceh and Papua: Is special autonomy the solution? East-West Center. https://www.eastwestcenter.org/system/tdf/private/PS010.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=32017

Mufti, L., & Rasidi, P. P. (2021, October 13). Selling the omnibus law on job creation. Inside Indonesia. https://www.insideindonesia.org/selling-the-omnibus-law-on-job-creation

Ong, J. C., & Tapsell, R. (2022). Demystifying disinformation shadow economies: Fake news work models in Indonesia and the Philippines. Asian Journal of Communication, 32(3), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2021.1971270

Safenet. (2022, May 3). 2021 digital rights in Indonesia situation report: The pandemic might be under control, but digital repression continues. https://safenet.or.id/in-indonesia-digital-repression-is-keep-continues/

Sarmento, P. D. C., & Mambor, V. (2020). West Papuan control: How red tape, disinformation, and bogus online media disrupts legitimate news sources. Pacific Journalism Review, 26(1), 105–113. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.361833687489438

Sastramidjaja, Y., Berenschot, W., Wijayanto, & Fahmi, I. (2021, October 13). The threat of cyber troops. Inside Indonesia. https://www.insideindonesia.org/the-threat-of-cyber-troops

Sinpeng, A., & Tapsell, R. (2021). From grassroots activism to disinformation: Social media trends in Southeast Asia. In A. Sinpeng, & R. Tapsell (Eds.), From grassroots activism to disinformation: Social media in Southeast Asia (pp. 1–18). ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

Strick, B., & Thomas, E. (2019, October 11). Investigating information operations in West Papua. Bellingcat. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/rest-of-world/2019/10/11/investigating-information-operations-in-west-papua-a-digital-forensic-case-study-of-cross-platform-network-analysis/

Daylight savings time around the world 2021. (2021). Timeanddate. https://www.timeanddate.com/time/dst/2021.html

Uyheng, J., & Carley, K. M. (2020). Bot impacts on public sentiment and community structures: Comparative analysis of three elections in the Asia-Pacific. In R. Thomson, H. Bisgin, C. Dancy, A. Hyder, & M. Hussain (Eds.), Lecture notes in computer science: Vol. 12269: Social, cultural, and behavioral modeling (pp. 12–22). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61255-9_2

Wangge, H. R., & Webb-Gannon, C. (2020). Civilian resistance and the failure of the Indonesian counterinsurgency campaign in Nduga, West Papua. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 42(2), 276–301. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26937803

Wickham, H. (2016). Ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org

Wickham, H., Averick, M., Bryan, J., Chang, W., McGowan, L. D., François, R., Grolemund, G., Hayes, A., Henry, L., Hester, J., Kuhn, M., Pedersen, T. L., Miller, E., Bache, S. M., Müller, K., Ooms, J., Robinson, D., Seidel, D. P., Spinu, V., Takahashi, K., Vaughan, D., Wilke, C., Woo, K., & Yutani, H. (2019). Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686

Wijayanto, & Berenschot, W. (2021). Organisation and funding of social media propaganda. Inside Indonesia. https://www.insideindonesia.org/organisation-and-funding-of-social-media-propaganda

Wiratraman, H. P. (2020, August 26). Veronica Koman case another nail in the coffin of intellectual freedom. Indonesia at Melbourne, The University of Melbourne. https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/veronica-koman-case-another-nail-in-the-coffin-of-intellectual-freedom/

Funding

No external funding was received for this project.

Competing Interests

There are no conflicts of interest associated with this submission.

Ethics

Our research methods were approved by the University’s Office of Research Ethics and Integrity prior to the project’s commencement.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OK7YOO

Due to restrictions from Twitter API v2 for Academic Research, we are only able to provide a severely limited version of the dataset used in this analysis, which is also deposited at the same URL.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of our sorely missed colleague Richard Chauvel to this research project, who died prior to write-up of the article. We also thank Jemma Purdey, Andrew Rosser, and Chris Wilson for their feedback, as well as the two anonymous peer reviewers. This article results from a 2021 Melbourne Data Analytics Platform collaboration.