Peer Reviewed

White consciousness helps explain conspiracy thinking

Article Metrics

2

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

While conspiracy theories have long been tied to race, ethnicity, and religion, understanding this relationship is increasingly important in countries where White identity has become politically charged. This study finds that those high in White consciousness are more likely to 1) engage in generalized conspiracy thinking, 2) endorse the racist “great replacement” conspiracy theory, and 3) move from generalized conspiracy thinking to endorsing specific, non-racial conspiracy theories. The link between White consciousness and conspiracy thinking has implications for those interested in mitigating its anti-pluralist outcomes.

Research Questions

- Does White consciousness help explain “great replacement” conspiracy beliefs?

- Are those high in White consciousness more likely to engage in generalized conspiracy thinking?

- Do White consciousness and conspiracy thinking interact when explaining non-racial conspiracy theory beliefs?

Essay Summary

- White consciousness is “a psychological, internalized sense of attachment” (Jardina, 2019, p. 4) to a White in-group (White identity) combined with “a political awareness or ideology regarding the group’s relative position in society along with a commitment to collective action aimed at realizing the group’s interests” (Miller et al., 1981, p. 474)

- I conducted a survey of White Canadians which measured their 1) levels of White consciousness, 2) levels of generalized conspiracy thinking, 3) beliefs about the so-called “great replacement” conspiracy theory, and 4) beliefs about several other, non-racial conspiracy theories.

- Those high in White consciousness were much more likely to endorse the “great replacement” conspiracy theory, which alleges that governments and corporations are purposely allowing foreigners into the country to replace White workers and culture. Only 57% of White respondents rejected this view outright, and those strongest in White consciousness were much more likely to espouse “great replacement” views than those weakest in it.

- Respondents’ levels of White consciousness strongly predicted levels of generalized conspiracy thinking, or the broad tendency to see the world as being controlled through secret plots by malevolent actors.

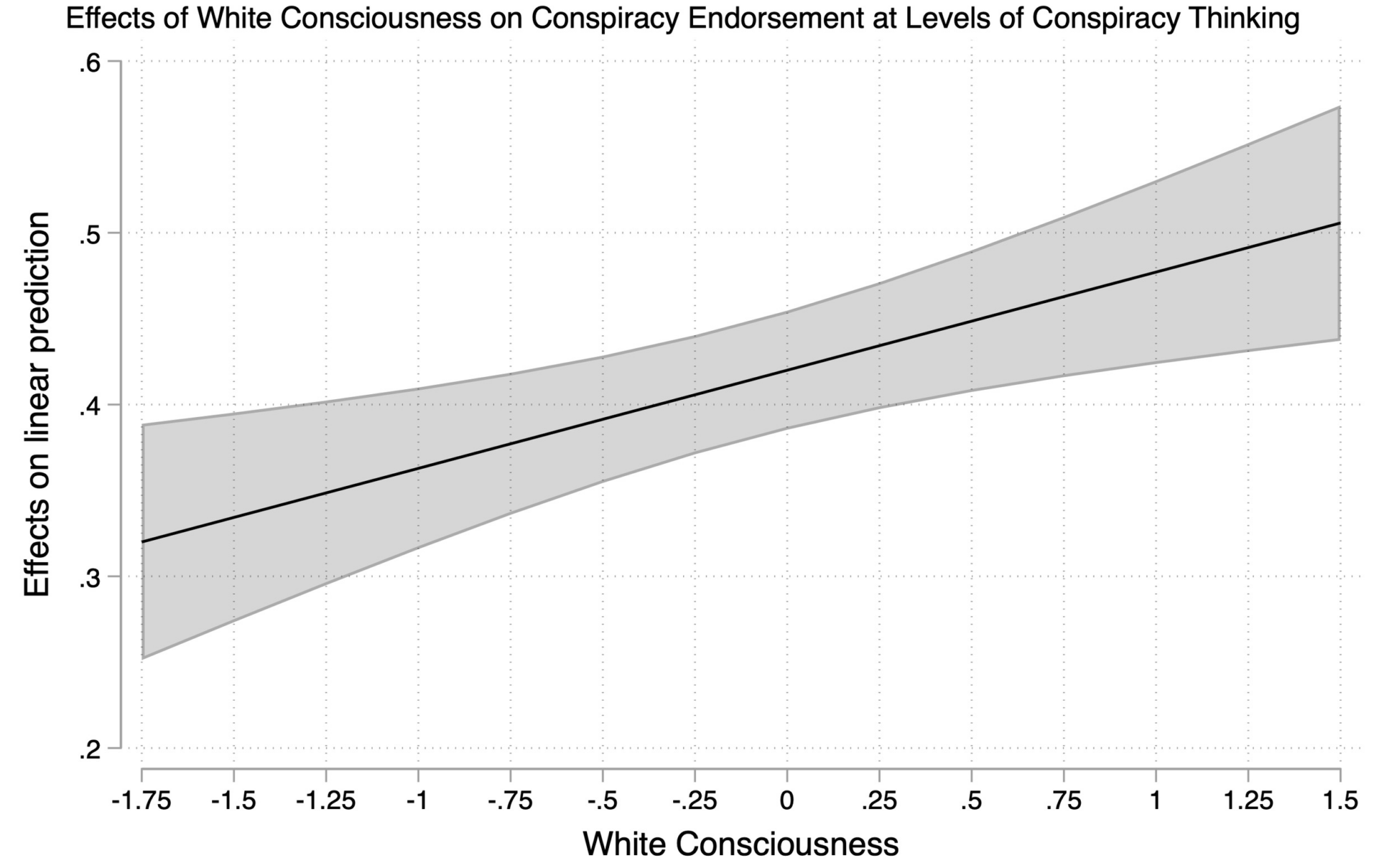

- White consciousness makes the effect of generalized conspiracy thinking stronger when predicting specific conspiracy theory endorsement, even for conspiracy theories that are not directly related to race, ethnicity, or religion. The impact of conspiracy thinking on non-racial conspiracy endorsement is almost 60% greater for those highest in White consciousness than those who are lowest.

- While conspiracy theories have long been tied to race, ethnicity and religion, researchers and practitioners interested in mitigating the harmful effects of White identity on conspiracy belief must first better understand the mechanisms linking them.

Implications

Conspiracy theories have long been closely tied to race, religion, and ethnicity. From antisemitic conspiracy theories in the high medieval period to the more recent “birther” conspiracy in the United States (Enders et al., 2020; Simonsen, 2020), the delineation of “us” and “them” along ethno-racial and religious lines promotes the belief that these groups are locked in a primordial, zero-sum contest, where better outcomes for one group leads to worse outcomes for another. In turn, this can lead members of more powerful groups to believe historically disadvantaged groups are conspiring to usurp power or otherwise subvert the established order. If we can better understand how and why ethnic and racial identities lead people to conspiracy beliefs, we can develop strategies to counteract their negative consequences.

I found that White identity is related to conspiracy thinking in at least three ways. First, the strength of White consciousness helps explain specific beliefs about the “great replacement” conspiracy theory: The explicitly racist view that governments and corporations are purposely promoting immigration to “replace” the White population with people of color for political and economic gain. Second, those high in White consciousness are more likely to engage in generalized conspiracy thinking. Here, conspiracy thinking refers to “an individual’s underlying propensity to view the world in conspiratorial terms” (Uscinski et al., 2016, p. 58), and corresponds to a set of stable attitudes in an ideological belief system (Imhoff & Bruder, 2014). Finally, I show that White consciousness and conspiracy thinking interact with each other, producing effects that are greater than the sum of their parts. Specifically, White consciousness makes conspiracy thinking stronger when it comes to non-racial conspiracy theory endorsement—that is, conspiracy theories that have no explicit link to relations between ethnic, racial or religious groups. Here again, conspiracy endorsement refers to belief in specific conspiracy theories (e.g., “climate change is a hoax”) versus conspiracy thinking, which refers to a generalized propensity to see the world in conspiratorial terms.

The longstanding relationship between White consciousness and conspiracy belief is important in a context where White identity has become increasingly consequential in advanced democracies. As a psychological attachment to a White in-group, White identity can become politicized into White consciousness if identifiers believe their future life prospects are tied to the outcomes of their group overall—in this case, of White people writ large (McClain et al., 2009). White identity is often activated by status threat, represented by any perceived challenge to the power or privilege that White people have historically enjoyed in racialized, White-majority societies. Jardina (2019) found that the election of President Barack Obama and the changing racial makeup of the United States signaled a challenge to Whites’ dominant position in society, thus triggering a perception that Whiteness is under attack. When confronted with their relative numerical decline in society, White people become more positively disposed towards other White people, more negatively disposed towards ethnic minorities, and more supportive of policies which promote the interest of their group at the expense of other groups (Beauvais & Stolle, 2022; Danbold & Huo, 2015; Outten et al., 2012). Indeed, conspiracy thinking often emerges in a context where a group feels threatened by outside forces seemingly beyond their control, led by a perception that malevolent forces are “out to get” them.

On one hand, these results should not be surprising; White people have created systems which favor themselves over other racial groups in White-majority countries, and since White identifiers (those who have a psychological attachment to a White in-group) tend to see inter-group relations in zero-sum terms (Snagovsky, 2020), they may be suspicious that the pursuit of racial equality will come at the expense of their privileged position in society. This explains why a stronger attachment to a White in-group is associated with the belief that powerful, secret, and malevolent forces control major events and thus pose a threat to the established order. This also suggests that stronger attachment to a historically privileged racial identity is tied to beliefs that this identity is under threat, which explains why White identifiers are more likely to believe themselves the victims of a secret plot to “replace” them.

On the other hand, the finding that White consciousness and conspiracy thinking interact to explain non-racial conspiracy theories is unexpected. Here, the impact of conspiracy thinking on the endorsement of non-racial conspiracy theories is almost 60% greater for those White respondents who were most firmly attached to their Whiteness, when compared to those White people most weakly attached to it. This suggests that while the impact of White identity may have started as a fear of other groups displacing pro-White power structures, it may have bled over into seeing conspiracies in all manner of places, from climate change to the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, it is worth noting that as a correlational study, this analysis cannot make any claims about causality, and alternative explanations for this relationship may be possible. In particular, more research is needed to understand how factors like left-right ideology affect these variables (beyond what is captured in the control variables).

How might researchers and practitioners develop strategies to weaken the pathway from White consciousness to conspiracy belief? Future research should examine which specific elements of White consciousness make conspiracy thinking stronger; is mere attachment to a powerful group enough to make group members think that other groups are out to get them, or is there something particular about White consciousness that triggers this relationship? Indeed, political elites, especially on the ideological right, have long sought to mobilize White grievance for political gain, in part by seeking to convince White people that they belong to a group which is under siege from globalist forces outside of their control. If it turns out there is something special about White consciousness, practitioners should turn their attention to discrediting the narratives promoted by these elites in the eyes of White identifiers specifically; untargeted, broad-based condemnation of these views is unlikely to be enough. On the other hand, if being attached to any privileged identity is enough to stimulate conspiracy thinking, practitioners should examine ways to convince White identifiers that inter-group relations need not lead to zero-sum outcomes, where gains for one group represent losses for another.

Finally, this study was conducted in Canada, a diverse settler society where racial and ethnic relations are much less polarized than in a country like the United States. In this respect, Canada is much more comparable to other advanced democracies, such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and others in Western Europe. The fact that White consciousness has such powerful consequences for conspiracy belief in this context should serve as a wake-up call for those who are inclined to think that this relationship is only relevant in a country like the United States. Indeed, the impacts of White consciousness transcend the “usual suspects,” and it is imperative to better understand its impacts in a global context.

Findings

Finding 1: Those high in White consciousness are more likely to believe in the “great replacement” conspiracy theory.

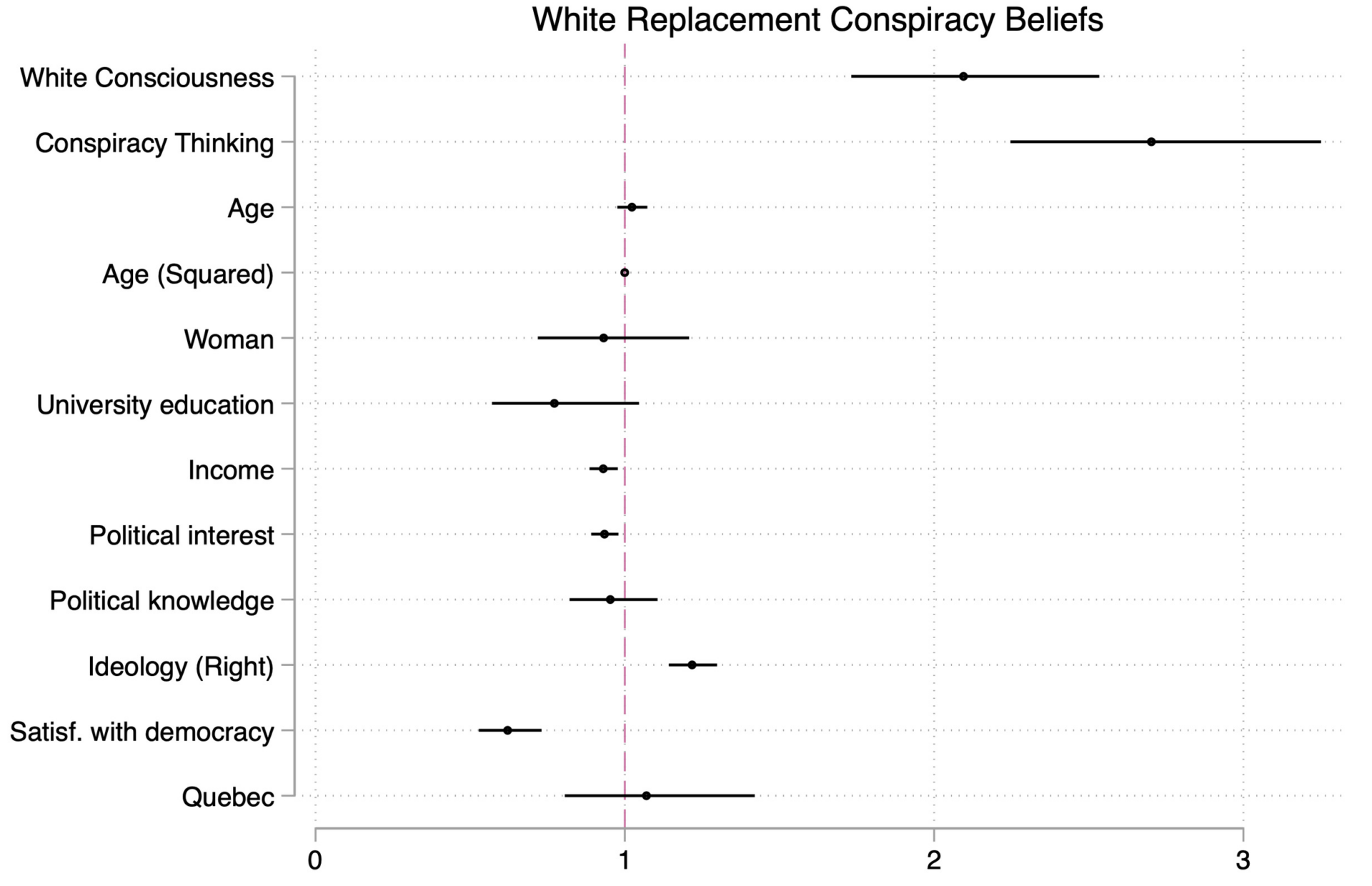

I created indices which measured respondents’ attachment and political commitment to a White racial identity (White consciousness) as well as their tendency to engage in conspiracy thinking. The strength of White consciousness predicted specific beliefs about the so-called “great replacement” conspiracy theory, as measured by the view that “governments and corporations are purposely allowing foreigners into the country to replace White workers and culture.” Only 57% of White respondents rejected this view outright, with 13% believing it was more likely to be true than a non-conspiratorial alternative, and an additional 18% thought the two were equally likely (12% were not sure). However, as Figure 1 shows, for every standard deviation unit increase in the strength of White consciousness, there is a 2-times increase in the odds ratio of moving up one point in endorsing this conspiracy theory (i.e., moving from rejecting the view to thinking it was plausible, or from thinking it was plausible to endorsing this view).

These effects were present even after controlling for generalized conspiracy thinking, where an increase of one standard deviation unit was associated with a 2.6-unit increase in the odds ratio of endorsing this specific conspiracy. This represents a greater increase than the strength of White consciousness, though the two effects are not statistically different from each other. Many of the same predictors of conspiracy thinking also explained attitudes towards the great replacement conspiracy theory: Those who were more politically interested, less satisfied with democracy, and more right-wing were more likely to endorse this view. Wealthier respondents were less likely to endorse the White replacement conspiracy theory, an effect which was not present for conspiracy thinking in general.

Finding 2: Those high in White consciousness are more likely to engage in conspiracy thinking.

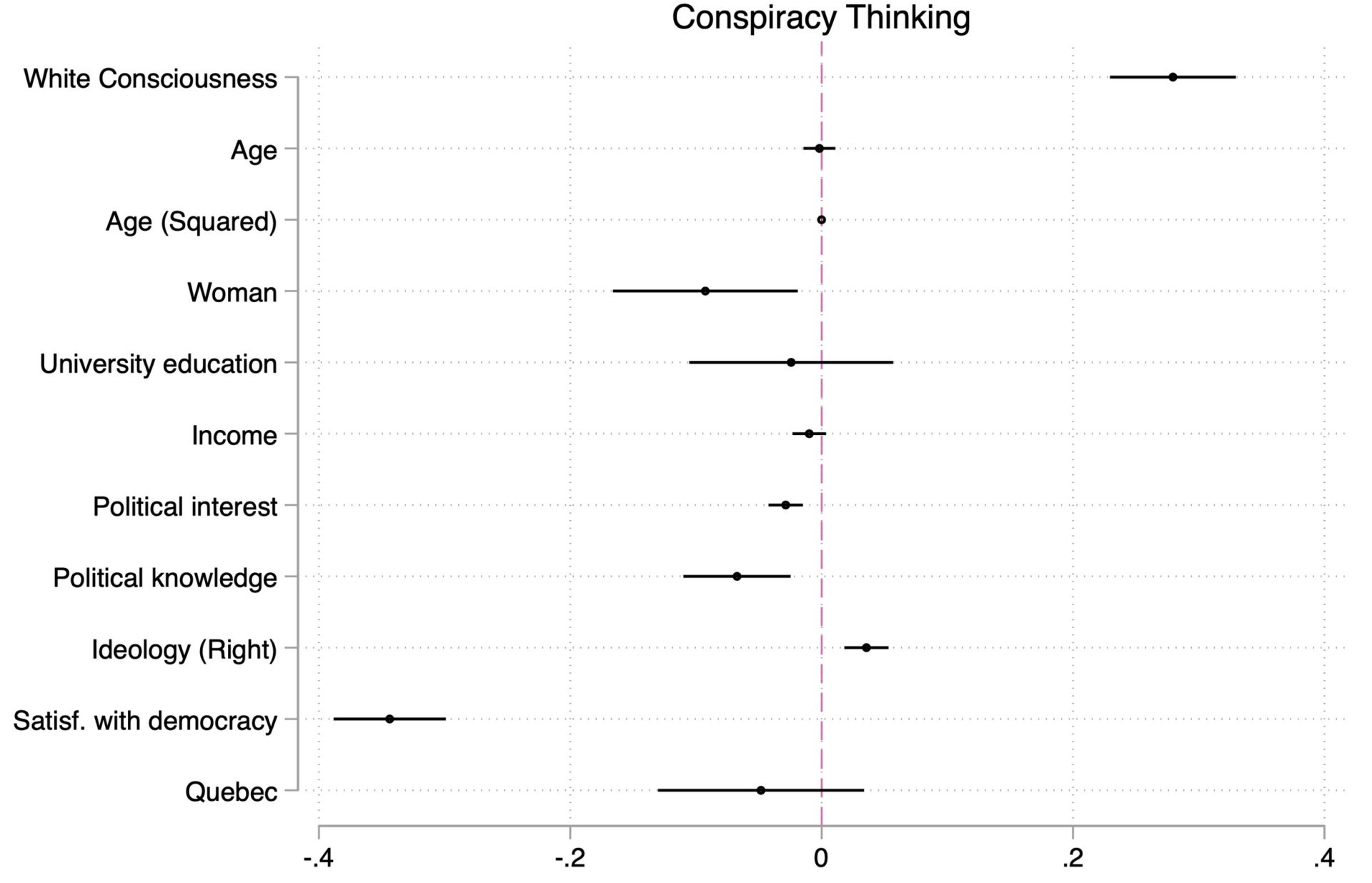

As Figure 2 shows, there is a strong relationship between White consciousness and conspiracy thinking: As the strength of White consciousness increases, so too does the likelihood that a respondent engages in conspiracy thinking. This relationship is present even when accounting for several alternative explanations of conspiracy thinking, including age, gender, education, income, political interest, political knowledge, right-wing ideology, satisfaction with democracy, and whether the respondent lives in the Canadian province of Québec. For every standard deviation unit increase in the strength of a respondent’s White consciousness, the respondents’ level of conspiracy thinking is likely to be 0.28 standard deviation units greater. This is a strong relationship. Women, those who were more satisfied with democracy, those with higher levels of political interest, and those with greater political knowledge were also less likely to engage in conspiracy thinking. By contrast, respondents who self-identified as being on the right of the political spectrum were more likely to engage in conspiracy thinking. As Appendix G shows, part of this relationship is driven by ethno-racial consciousness more broadly, as ethnic minority respondents higher in ethnic consciousness also have higher levels of conspiracy thinking. However, the effect is stronger for White respondents, and the difference between the groups is statistically significant (p < .05).

Finding 3: White consciousness makes the effect of conspiracy thinking stronger, even for non-racial conspiracy theories.

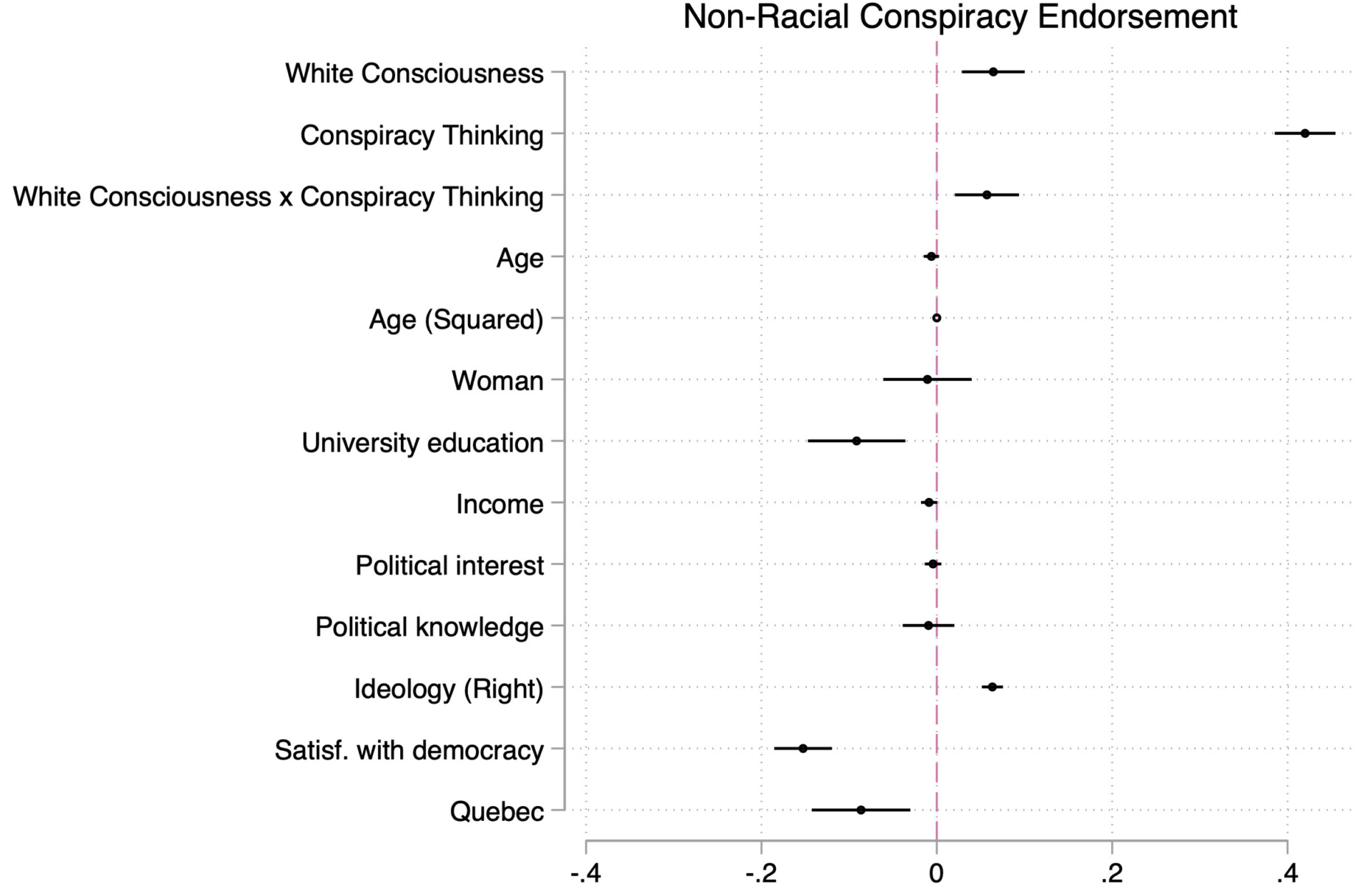

While White consciousness predicts conspiracy thinking, and both help predict “great replacement” beliefs, White consciousness also makes conspiracy thinking stronger when it comes to non-racial conspiracy theories. Figures 3 and 4 show the results of an interaction between White consciousness and conspiracy thinking. Here, the dependent variable is an index where higher values correspond to greater belief in a range of non-racial conspiracy theories, including those about COVID-19 and vaccines, climate change, the World Economic Forum (WEF), the “deep state,” “15-minute cities,” and election interference.

As Figures 3 and 4 show, White consciousness interacts with conspiracy thinking when explaining non-racial conspiracy beliefs, even when controlling for a range of other explanatory factors. While conspiracy thinking is the strongest determinant of non-racial conspiracy endorsement, the strength of its impact depends on respondents’ level of White consciousness: At the lowest level of White consciousness, a one standard deviation rise in conspiracy thinking increases beliefs about non-racial conspiracies by approximately 0.32 standard deviations. By contrast, at the highest level of White consciousness, the effect of conspiracy thinking rises to 0.51 standard deviation units (representing a 58% increase). University education, living in Québec, and greater satisfaction with democracy are all associated with a lower level of conspiracy endorsement, while right-wing self-placement continues to be associated with a greater level of conspiracy endorsement in this model.

Methods

I conducted a survey of Canadian adults, which was administered through Qualtrics and fielded through Cint/Lucid Marketplace from April 21–May 01, 2023. The sample was stratified according to age, gender, and province, and was deployed in both English and French. After White respondents were isolated from the broader sample, I was left with 1,556 valid responses. The characteristics of White respondents according to sampling criteria (age, gender, province) closely matched those of non-visible minority Canadians according to the 2021 census (see Appendix A).

I followed Uscinski et al. (2016) in measuring conspiracy thinking using a four-item, 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree):

1. Much of our lives is being controlled by plots hatched in secret places.

2. Even though we live in a democracy, a few people will always run things anyway.

3. The people who really ‘run’ the country, are not known to the voters.

4. Big events like wars, the current recession, and the outcomes of elections are controlled by small groups of people who are working in secret against the rest of us.

A Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.83 indicates the scale had excellent internal consistency.

I adapted the approach advanced by Clifford et al. (2019) to measure conspiracy endorsement in which they argue offering respondents a binary choice of two statements (one corresponding to a conspiracy theory and the other to a “conventional” explanation for a phenomenon) produces more accurate estimates than Likert-type questions. I modified this approach to include a third option indicating “both of these are equally likely.” White replacement was measured by asking which of the following statements was most likely to be true (with additional options for “both of these are equally likely” and “not sure”): “Governments and corporations are purposely allowing into the country to White workers and culture” or “Immigration decisions in Canada are made on economic and humanitarian grounds.” The responses were recoded into a 3-point scale corresponding to an ordinal variable ranging from least to most conspiratorial (1 = non-conspiracy theory statement, 2 = both of these are equally likely, and 3 = conspiracy theory statement).

Respondents answered in the same format for nine non-racial conspiracy theories, choosing between two sets of statements. While the exact question wording is available in Appendix B, these conspiracy theories touched on the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, the World Economic Forum (WEF), the “deep state,” “15-minute cities,” and election interference. Responses were re-coded into a three-point scale as per above. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 indicated the scale had excellent internal consistency.

I expanded Jardina’s (2019) White identity battery into an eight-item measure of White consciousness:

1. How important is being White to your identity?

2. How strongly do you identify with other White people?

3. What happens to White people in this country will have something to do with what happens in my life.

4. When people criticize White people, it feels like a personal insult.

5. When I meet someone who is White, I feel connected with this person.

6. When I speak about White people, I feel like I am talking about “my” people

7. When people praise White people, it makes me feel good.

8. I have a strong attachment to other White people.

Items 1 and 2 were asked as stand-alone questions, while respondents were asked to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with the statements in items 3–8. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.9 indicates excellent internal scale consistency. All three scales (conspiracy thinking, conspiracy endorsement, and White identity) were standardized to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1.

The estimates in Figures 1, 3, and 4 come from ordinal least squares (OLS) regression since the dependent variables (conspiracy thinking and conspiracy endorsement) are continuous. The estimates in Figure 2 are odds ratios from an ordinal logistic regression since the dependent variable (White replacement beliefs) corresponds to a three-point scale. All models control for age (both as years and as years-squared to account for curvilinear effects), gender, university education, income, political interest, political knowledge, left-right ideological self-placement, satisfaction with democracy, and whether the respondent lives in Québec (see Appendix B for exact question wording).

Topics

Bibliography

Beauvais, E., & Stolle, D. (2022). The politics of White identity and settlers’ indigenous resentment in Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 55(1), 59–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423921000986

Clifford, S., Kim, Y., & Sullivan, B. W. (2019). An improved question format for measuring conspiracy beliefs. Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(4), 690–722. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz049

Danbold, F., & Huo, Y. J. (2015). No longer “all-American”? Whites’ defensive reactions to their numerical decline. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(2), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614546355

Enders, A. M., Smallpage, S. M., & Lupton, R. N. (2020). Are all ‘birthers’ conspiracy theorists? On the relationship between conspiratorial thinking and political orientations. British Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 849–866. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000837

Imhoff, R., & Bruder, M. (2014). Speaking (un-)truth to power: Conspiracy mentality as a generalised political attitude. European Journal of Personality, 28(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1930

Jardina, A. (2019). White identity politics. Cambridge University Press.

McClain, P. D., Johnson Carew, J. D., Walton Jr, E., & Watts, C. S. (2009). Group membership, group identity, and group consciousness: Measures of racial identity in American politics? Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.102452

Outten, H. R., Schmitt, M. T., Miller, D. A., & Garcia, A. L. (2012). Feeling threatened about the future: Whites’ emotional reactions to anticipated ethnic demographic changes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211418531

Simonsen, K. B. (2020). Antisemitism and conspiracism. In M. Butter & P. Knight (Eds.), Routledge handbook of conspiracy theories (pp. 357–370). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429452734

Sorell, T., & Butler, J. (2022). The politics of Covid vaccine hesitancy and opposition. The Political Quarterly, 93(2), 347–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13134

Uscinski, J., Klofstad, C., & Atkinson, M. (2016). What drives conspiratorial beliefs? The role of informational cues and predispositions. Political Research Quarterly, 69(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912915621621

Velicer, W. F., Eaton, C. A., & Fava J. L. (2000). Construct explication through factor or component analysis: A review and evaluation of alternative procedures for determining the number of factors or components. In R. D. Goffin & E. Helmes (Eds.), Problems and solutions in human assessment: Honoring Douglas N. Jackson at seventy (pp. 41–71). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4397-8_3

Watkins, M. (2021). A step-by-step guide to exploratory factor analysis with Stata. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003149286

Widaman, K. F. (2018). On common factor and principal component representations of data: Implications for theory and for confirmatory replications. Structural Equation Modeling, 25(6), 829–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2018.1478730

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (grant number 430-2022-00204).

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethics

The research protocol for this study was approved by the University of Alberta Human Research Ethics Board (Pro00113410). Survey participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the survey. Gender categories used in the study were defined by the researcher and were necessary to examine whether different gender groups had different levels of conspiracy endorsement.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BS9OAZ