Peer Reviewed

Designing misinformation interventions for all:

Perspectives from AAPI, Black, Latino, and Native American community leaders on misinformation educational efforts

Article Metrics

3

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

Page Views

This paper examines strategies for making misinformation interventions responsive to four communities of color. Using qualitative focus groups with members of four non-profit organizations, we worked with community leaders to identify misinformation narratives, sources of exposure, and effective intervention strategies in the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI), Black, Latino, and Native American communities. Analyzing the findings from those focus groups, we identified several pathways through which misinformation prevention efforts can be more equitable and effective. Building from our findings, we propose steps practitioners, academics, and policymakers can take to better address the misinformation crisis within communities of color. We illustrate how these recommendations can be put into practice through examples from workshops co-designed with a non-profit working on disinformation and media literacy.

Research Questions

- How do leaders in AAPI, Black, Latino, and Native American interest organizations perceive the scope and threat of misinformation in their communities?

- How do misinformation narratives interact with the cultural values and histories of communities of color?

- What community strengths and resources can be leveraged to combat the spread of misinformation?

- How can misinformation interventions be designed to be culturally relevant and responsive?

Essay Summary

- We qualitatively investigated community leaders’ perspectives on misinformation via in-depth focus groups conducted with four non-profit organizations: Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAAJ), Mi Familia Vota (MFV), the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), and the National Action Network (NAN).

- Efforts to combat misinformation should include multilingual options to help people find and navigate trusted sources of information in their native languages.

- Misinformation education initiatives should account for diverse media ecologies, including diasporic social media communities (e.g., Black Twitter), ethnic print and broadcast media (e.g., Indian Country Today), and messaging platforms popular among certain communities of color (e.g., WhatsApp, Line).

- Approaches to reducing trust in misinformation while building trust in credible information in communities of color should acknowledge reasons for institutional distrust in historically marginalized communities and employ messaging approaches that are sensitive and empathetic to community concerns.

- Based on the perspectives of community leaders, we describe a set of best practices for designing inclusive misinformation interventions. To illustrate how these recommendations can be implemented in interventions, we provide concrete examples from the PEN America Disinformation Defense Workshops.

Implications

Misinformation threatens society by undermining people’s trust in institutions, organizations, and one another. The internet and social media platforms play a key role in its spread. Despite efforts from technology platforms, misinformation continues to proliferate across our digital world, from viral hoaxes promising false cures for COVID-19 to posts inspiring violent protests (Moore et al., 2022).

While misinformation harms everyone, the costs are not borne equally. In the United States, communities of color are disproportionately targeted and impacted by disinformation campaigns. As shown by misinformation surrounding COVID-19, false information can exacerbate health disparities by discouraging individuals from accessing health resources and increasing doubt in medical systems. For instance, Latino communities across the United States have been exposed to misinformation narratives purporting that the pandemic is a hoax, vaccines cause infertility, and treatments or vaccinations require proof of identification or insurance (Longoria, 2021; Mochkofsky, 2022; Navia, 2021; Nguyen & Catalan, 2020; Soto-Vasquez et al., 2020). Similarly, recent research on misinformation narratives targeting Black Americans on social media found that anti-vaccine messaging often evokes concerns about medical racism and exploitation (e.g., the Tuskegee syphilis crisis, Dodson et al., 2021) and ongoing structural inequalities (e.g., medical redlining, Andrasfay et al., 2021; racism in healthcare, Diamond et al., 2022) to discourage people from getting vaccinated (Dodson et al., 2021). Harmful narratives discouraging vaccination and endorsing pseudoscientific cures can also be found across Asian American/Pacific Islander and Native American/American Indian communities (Asian American Disinformation Table, 2022; Getahun, 2021; Nguyễn et al., 2022). These examples of misinformation are particularly concerning given ongoing racial disparities in the impact of COVID-19. Relative to white people, BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, & People of Color) face higher risks of infection, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19 (Hill & Artiga, 2022) and other chronic diseases (Baciu et al., 2017).

Misinformation also threatens BIPOC’s ability to participate fully in civic processes. Indeed, misinformation purveyors have been shown to specifically target their campaigns towards communities of color in efforts to influence their votes (Freelon et al., 2020; Soto-Vásquez et al., 2021). Analysis of the Internet Research Agency’s attack on the 2016 U.S. presidential election revealed that their disinformation campaign on social media targeted Black voters by spreading fraudulent information about political candidates and election outcomes. Specifically, Gallon (2020) estimates that millions of dollars were spent on digital ads deployed across the internet to dissuade Black Americans from voting. More recently, political analysts expressed concern about waves of Spanish-language misinformation being deployed en masse to influence Latino voters ahead of the 2022 midterm elections (Cortina & Rottinghouse, 2022; Seitz & Weissert, 2021). Purveyors of misinformation, including foreign information operations (Beers et al., 2022; Starbird et al., 2019; Wilson & Starbird, 2020) and authoritarian governments (Lu et al., 2022) can rapidly translate false claims across popular platforms and within close online communities. Political misinformation seeking to disenfranchise or mislead specific individuals can harm BIPOC’s ability to participate in their government, thus undermining democratic processes and responsiveness. Furthermore, while belief in misinformation can have important normative consequences (e.g., votes cast in an election that are informed by false information about candidates or issues), the nature of social spaces on the internet (i.e., people connected in networks) means that an individual’s decision to share misinformation can affect their friends, family, and neighbors.

Efforts to spread misinformation have clearly adapted to speak to—and exploit—the concerns of communities of color. Thus, efforts to combat misinformation must keep up by ensuring that they are responsive to the strengths and needs of respective communities. One promising avenue for building misinformation resilience is digital media literacy interventions. They work to combat misinformation by equipping individuals with the skills to critically evaluate claims they encounter online (Breakstone et al., 2021; Breakstone et al., 2022; Moore & Hancock, 2022; Wineburg & McGrew, 2019). Rather than simply teaching individuals to trust or distrust specific sources, digital literacy interventions teach skills like lateral reading, which involves opening multiple tabs or windows to examine the veracity of a claim by comparing multiple sources and referencing fact-checking resources. The goal of teaching these skills is that people can use them to make more informed judgments about whether any piece of content encountered online is factual or fictional.

While teaching digital media literacy alone is unlikely to solve the misinformation crisis alone (boyd, 2018), it is important to examine whether it can support diverse audiences in evaluating the news they encounter. Indeed, the Aspen Institute’s Commission on Information Disorder report (2021) argues that bolstering digital media literacy is a key response required to overcome the misinformation crisis, noting that everyday people “need to understand how information reaches them and have the tools that can help them distinguish fact from falsehood, honesty from manipulation, and the trustworthy from the fringe” (p. 66). Equipping individuals with the skills they need to evaluate the veracity of online claims can complement parallel efforts to combat misinformation at the platform and legislative levels. In teaching these skills, we note that care must be taken to ensure that interventions do not urge individuals to distrust all news or to only “fact-check” news that does not align with their preexisting beliefs (Batailler et al., 2022; boyd, 2018). Rather, successful digital media literacy interventions should not only decrease individuals’ trust in false news, but also increase their trust in true news—a concept referred to as discriminant trust (Moore & Hancock, 2022).

While additional rigorous research is required to examine digital literacy interventions in general (Moore & Hancock, 2022), there is virtually no research on the efficacy of digital literacy interventions for communities of color. Even though minority groups are disproportionately targeted by disinformation campaigns, most misinformation interventions have been developed for and tested with predominantly white, English-speaking populations (e.g., Saltz et al., 2021; Walther et al., 2014). This systematically excludes large communities of individuals who do not speak English as their native language. Beyond the need to increase the generalizability of research findings, research also needs to direct efforts to people in marginalized communities who can benefit the most from such interventions. This is especially true given that the costs of misinformation exposure in these communities, such as vaccine hesitancy or non-participation in civic elections, have the potential to compound ongoing inequities.

Efforts to combat misinformation should work alongside communities of color to develop and launch interventions that support their needs (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1996). Misinformation prevention initiatives should collaborate with local community members and leaders to ensure that interventions are true to community needs. Indeed, it is imperative to recognize that communities of color are not monoliths. The experiences of individuals who are part of the Asian diaspora, for example, can vary substantially within and across the Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean communities (Nguyễn et al., 2022). Furthermore, it may be important to account for generational differences in BIPOC communities (e.g., a recent immigrant vs. a third-generation child). As misinformation spreads across the world, those seeking to combat false information and restore trust in credible sources should acknowledge the diversity of the populations they serve and take steps to ensure their initiatives are equitable and inclusive. Collaborations with organizations that have on-the-ground experiences with misinformation in local communities can help guide efforts to meet needs while leveraging community strengths.

This project sought to meet the need for misinformation prevention initiatives for BIPOC communities by conducting focus groups with community leaders from organizations working with AAPI, Black, Latino, and Native American populations to learn about communities’ experiences with online misinformation. In this paper, we report on key findings regarding how individuals from different backgrounds experience and respond to disinformation, and present recommendations and examples for ways that misinformation interventions can be designed for greater inclusivity.

Evidence

We collaborated with the non-profit organization PEN America to conduct focus groups with community leaders from non-profit organizations serving AAPI, Black, Latino, and Native American communities. Our findings suggest that future prevention initiatives should focus on:

1) Improving access to accurate multilingual information. The translation of educational materials, interventions, and resources into non-English languages should be a priority. Across communities, the focus groups highlighted the difficulty of finding timely, in-language information regarding health and politics. Whereas false news is often readily available in multiple languages (Chu et al., 2021), particularly on platforms like WeChat and WhatsApp (Zhang, 2017), informational resources like fact-checks and digests are generally geared towards English-speaking audiences. Therefore, it is more difficult for individuals from specific communities (e.g., Spanish-speaking, Chinese-speaking) to stay up to date on current events and to protect themselves from misinformation.

It is important to prioritize translation accuracy in addition to accessibility. High-quality translations may be particularly important for information about health issues, given the prevalence of medical jargon and the consequences of mistranslations. In a notable example regarding COVID-19 vaccines, the Virginia Department of Health issued a notice to Spanish speakers that the vaccine “won’t be necessary” (“no sera necesario”) instead of saying it was not mandatory (Goodman, 2021). While this error was quickly rectified, multilingual access to resources continues to be limited as many organizations do not offer language support for vaccine-finder websites or other key sources of news (Howe et al., 2021). The rapid evolution of health crises like COVID-19 means that timely translation of breaking news and health guidelines is essential for providing communities of color with the information they need to make informed decisions to safeguard their health and well-being.

Representatives from multiple organizations emphasized that greater investments are needed to support local and national organizations in providing translations of credible news. Many current misinformation prevention interventions encourage people to use fact-checking resources such as PolitiFact or Snopes to evaluate the veracity of claims they encounter online (e.g., Badrinathan, 2021; Wineburg et al., 2022). However, community members at MFV and AAAJ described how these resources often have limited availability in non-English languages, such as Spanish, Vietnamese, and Chinese. Although some organizations, such as the Agence France-Presse, make fact-checks available in a variety of languages besides English, translations are often only provided for a subset of articles. As a result, it is often more difficult for multilingual individuals to apply the digital media literacy skills taught in misinformation interventions due to having fewer trustworthy sources to compare across.

While making trustworthy information available in diverse languages is necessary to make misinformation interventions more accessible to people of all backgrounds, focusing on language alone is not a panacea. Educational efforts should acknowledge and center the experiences of individuals from BIPOC communities in the content they create, as well.

2) Collaborating with trusted messengers from social media networks and ethnic media outlets. Accounting for diverse media ecologies when developing educational content about misinformation is critical when considering pathways for disseminating interventions. The focus group participants emphasized that in addition to mainstream news outlets (e.g., CNN, BBC), many individuals received information from formal and informal ethnic media sources. As a result, interventions aiming to teach individuals to effectively evaluate claims should include examples of investigating dubious claims from a variety of media sources, in addition to collaborating with in-network trusted messengers to promote credible information.

Media ecologies varied by community. For instance, broadcast channels such as Univision and Telemundo were noted as being particularly influential in the Latino community. Similarly, NCAI members said that tribal news sites (e.g., Indian Country Today) and tribal health services (e.g., Indian Health Services, Seneca Nation Health System) tended to be regarded as central sources of trusted information. Ethnic social media communities and channels were also important to sharing information within close networks, like family and friend group chats, and the community at large. For instance, social media channels like WeChat, WhatsApp, and KakaoChat were listed as being particularly important in the AAPI community, in part because of their support of Asian languages and their widespread use internationally. Informal social media networks like Black Twitter were central to sharing information among Black Americans, particularly as a means of sharing personal experiences and highlighting issues relevant to the diasporic community. In addition to peer-to-peer networks like Black Twitter, outlets like NextShark—a news outlet targeted towards Asian American interests—were also popular sources of information on social media. Members of all four non-profits also cited public health institutions (e.g., the CDC, the WHO) as important sources of news about issues such as COVID-19 for people of all ages, in addition to the importance of radio and TV among older individuals.

Across all of the listening sessions, people highlighted social media as a dominant source of misinformation. Facebook, TikTok, and Twitter were named as being particularly notorious for exposing individuals to false information about political issues and health news. However, participants also discussed the role of private messaging apps and group chats in spreading misinformation. For instance, community members from both MFV and AAAJ described instances where people shared false information in their group chats, which was rapidly forwarded to many other individuals within their networks before being fact-checked.

Because misinformation is often propagated accidentally by peers within one’s community, trusted messengers can play an important role in stopping its spread. One reason why certain media outlets or sources are trusted (e.g., Univision) is because they provide support for different languages. Therefore, diversifying language resources by providing multilingual translations for key health organizations like the CDC or fact-checking groups like AP News can not only convey timely information to BIPOC communities, but also build trust in information resources.

3) Addressing the role of history and culture in dominant misinformation narratives. Misinformation narratives are adept at tapping into and exploiting community concerns, and interventions need to be developed within this contextual understanding. Focus group participants described encountering specific iterations of common misinformation narratives that sought to tap into historical and cultural tensions (e.g., distrust of federal institutions stemming from historical injustices and ongoing discrimination). For instance, individuals from every focus group discussed hearing generic claims about how the COVID-19 vaccine worked (e.g., that the shot contained active COVID-19 particles and would infect you), its side effects (e.g., that the shot would cause infertility or heart disease), and its development (e.g., that its current administration was “experimental”). However, organizers from MFV noted that misinformation targeting Latino individuals tended to focus on putting up barriers to access, such as by saying that proof of identification, residence documentation, or payment was required to get a COVID-19 vaccine. They also mentioned that there was little reliable information available on how to ask employers for time off to recover from the vaccine’s side effects or how to ask doctors for more information about symptoms. These narratives were perceived as contributing to ongoing disparities in COVID-19 vaccination rates among Latino people.

In another example, AAAJ discussed how common misinformation narratives about COVID-19 tapped into cultural practices or beliefs about home remedies from AAPI communities. Group chats, for example, frequently circulated pseudoscientific and potentially dangerous “cures” (e.g., drinking boiling water or eating garlic to kill the COVID-19 virus). Representatives from the NCAI highlighted that though Tribal vaccination rates have been high, vaccine hesitancy often stems from institutional distrust of federal initiatives, given the United States government’s historical betrayal of Native communities. Individuals from the National Action Network shared similar sentiments regarding Black Americans’ concerns about medical racism. Many ethnic communities in the United States have experienced and continue to experience discrimination in relation to their ability to access healthcare resources, information, and basic needs. These historical injustices, such as the Tuskegee syphilis study, remain salient for many individuals, who may distrust federal institutions or public health initiatives. Efforts to address these types of misinformation should be sensitive to historic and ongoing systemic disparities that influence how people make decisions about their health and civic engagement. Beyond addressing the prevalence of false information, local and public organizations must work to address these disparities in order to rebuild trust.

Crucially, efforts to make interventions more inclusive should not presume BIPOC individuals’ reasons to trust or distrust information sources. Rather, interventions should aspire to recognize and be empathetic to the cultural and historical experiences that may be relevant to their experiences. Scholars and practitioners need to be careful that their tailoring efforts do not become stereotyping or labeling. For instance, facilitators should be prepared to discuss a variety of concerns about subjects like vaccinations, including those informed by cultural and historical experiences, but should not presume to know any individual’s personal reasoning based on their identities alone (e.g., assuming that an Asian American person is vaccine-hesitant because they only believe in Eastern medicine). As Dodson et al. (2021) discuss, we should remember that people have a variety of reasons for distrusting information sources beyond reasons related to cultural or historical experiences. Furthermore, it is essential to recognize misinformation can have complex effects across communities, as well as within communities. For instance, false claims can drive wedges between different BIPOC communities (e.g., between Blacks and Asian Americans around the topic of affirmative action; Asian American Disinformation Table, 2022) or inflame intergroup tensions. On the other hand, however, the interconnected nature of information ecologies means that addressing misinformation in one community may also uplift others. Future work should pursue means for explaining pathways to enhancing intergroup solidarity.

Recommendations and implementation. How can scholars and practitioners address these issues in their work? Below, we propose recommendations for improving misinformation resiliency education. To illustrate how these can be implemented in a real-world context, we detail how we put these recommendations into practice in the PEN America Disinformation Defense workshops, a series of workshops designed with the findings of our focus groups in mind.

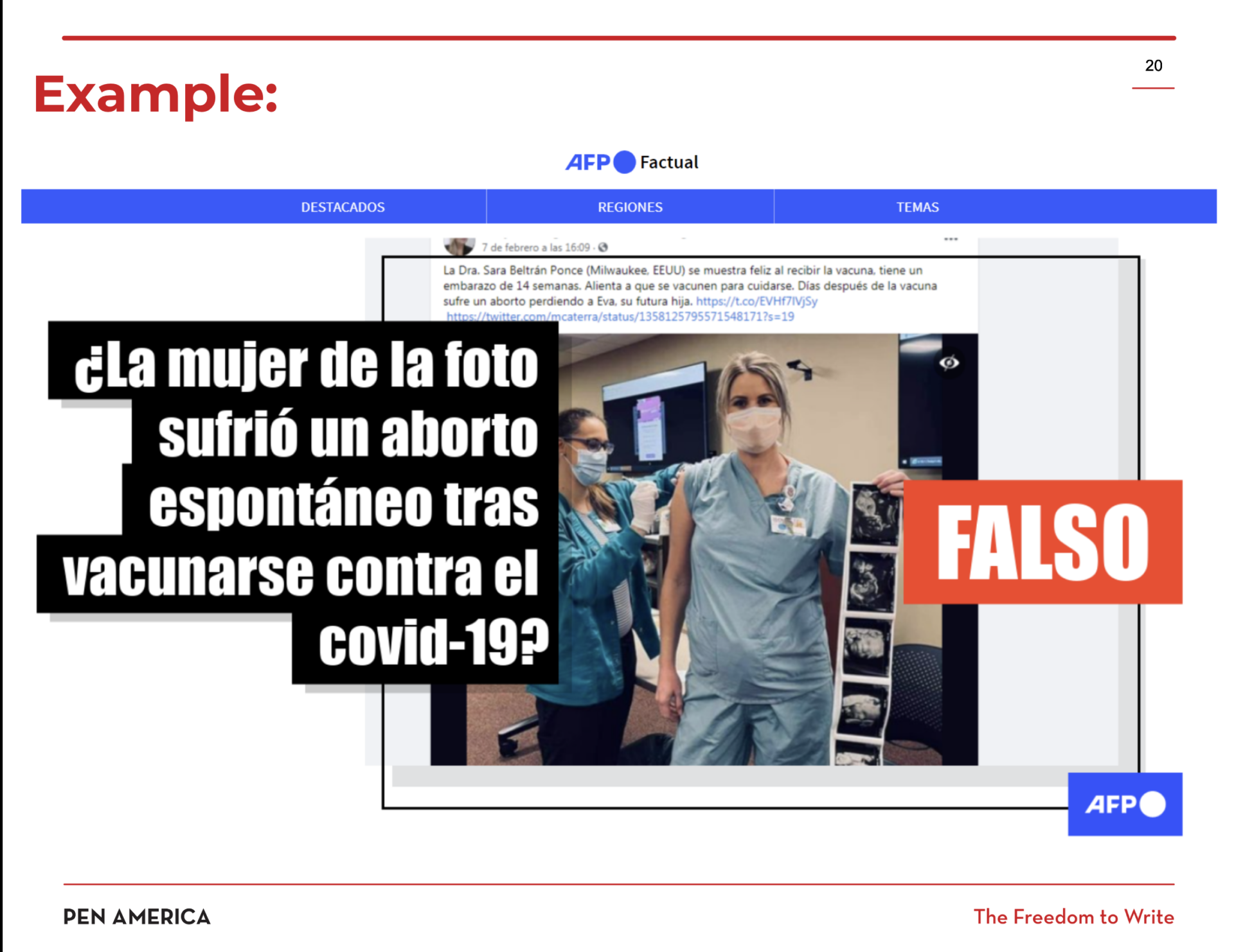

1. Include multilingual support. The first finding from our focus groups was that interventions need to improve access to accurate multilingual information, which often means that educational materials need to be translated such that they can be made available in the languages relevant to a particular community. In the PEN America Disinformation Defense Workshops, for example, Spanish speakers translated all of the educational materials (e.g., surveys, slides, resource packets) into Spanish for the workshops serving the Latino community. In addition, facilitators coordinated with community members to identify in-language examples of misinformation to integrate into the workshop (see Figure 1) and to share links to specific organizations that provided in-language fact-checks (e.g., Univision’s El Detector, see Figure 2). In digital settings, interventions can leverage captioning, live translation, and listen-along features to provide support to multilingual participants who may opt to listen in non-English languages.

2. Contextualize diverse media ecologies. Educational efforts can also account for communities’ diverse media ecologies by highlighting a variety of sources of trusted information, including ethnic media organizations, and by discussing how to address misinformation across a variety of platforms. These sources should be identified with community members’ input.

For instance, based on our findings from the focus groups, the PEN America Disinformation Defense workshop for Native American communities included a resource packet containing trusted information sources identified by NCAI, such as links to the Indian Country Today’s coverage of COVID-19, as well as the NCAI’s list of COVID-19 resources for Indian Country. As shown below, based on findings from the focus groups, the educational materials for the intervention in the AAPI community were also designed to include a module on how misinformation spreads in specific Asian communities (see Figure 3).

3. Prebunk false claims targeting the community. Finally, initiatives to combat misinformation in BIPOC communities can address known sources of misinformation by explicitly calling out and “prebunking” false claims before individuals are exposed to them (Lewandowsky et al., 2020). Prior research demonstrates that educators can build resilience to misinformation by debunking common false claims before people are exposed to them (Basol et al., 2021). Preemptively educating individuals about misinformation can “inoculate” them and reduce their risk of believing and sharing these claims, should they encounter them later (Basol et al., 2021; Traberg et al., 2022). Intervention facilitators can use this approach by explaining the specific ways in which disinformation campaigns target communities of color, and by training community members to be aware and vigilant to claims targeting their networks. As shown in Figure 4, the workshops PEN America co-designed with the four partner organizations included interactive components by hosting an open Q&A session where participants could ask doctors who shared their identities about health-related topics and misinformation. As part of this Q&A, facilitators prebunked common misinformation narratives about pseudoscientific cures for COVID-19 and side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine they had seen and heard in each community.

Methods

Procedure. We collaborated with PEN America, a literary and human rights non-profit organization, to understand BIPOC communities’ experiences with misinformation. Members of PEN America conducted in-depth qualitative focus groups, the transcripts of which were then analyzed by members of the Stanford University research team. We worked with PEN America on their in-depth qualitative focus groups with community members and leaders from four partner organizations that are led by and serving communities of color: Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAAJ), Mi Familia Vota (MFV), the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), and the National Action Network (NAN). Community leaders also identified as being from the communities they served. These organizations were selected due to their deep connections and credibility in the communities they serve and their interest in co-developing intervention and outreach materials (see the Appendix for more information about the organizations).

All focus groups were conducted between June 2021 and August 2021. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, sessions were conducted online over Zoom. PEN America asked members to discuss open-ended question prompts and allowed space for follow-up questions and conversation. The interview protocol was developed in order to elicit community members’ perspectives on (1) common sources of misinformation and credible information, (2) dominant narratives around misinformation, and (3) strategies for effectively combating false information within their communities. Written summaries of the key observations and insights from each listening session were drafted, which included detailed notes, exemplar quotes, and practical takeaways. No identifying information was recorded from participants. The facilitators read back the core learnings to the focus group participants at the end of each session to ensure they accurately captured key insights.

Focus groups were conducted by members of PEN America’s Knowing the News team, an initiative to address misinformation in communities of color. De-identified transcripts from the focus groups were analyzed by the Stanford University research team. We note that the research was non-evaluative of the PEN America program or the organization’s mission. The research was conducted to specifically interrogate how individuals from diverse ethnic groups experienced the threat of misinformation. No members of the Stanford University research team are, or have been, employees of PEN America.

Participants. A total of ten focus groups were conducted, comprising a total of 95 individuals. Participants included field organizers (n = 11) and state directors (n = 20) from MFV; Tribal youth commission members (n = 12) and Tribal leaders (n = 16) from NCAI; youth leaders (n = 12) and organization members (n = 10) from AAAJ; and chapter leaders (n = 6) from NAN. All focus groups were conducted with representatives from each of the individual organizations.

Data analysis. We analyzed the transcripts of the focus groups using thematic content analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This analytical approach allowed us to identify central themes in the focus group data. While there are different forms of content analytic methods that can be used to analyze qualitative data, we selected a thematic analytic approach based on Braun & Clarke (2006), which emphasizes providing a qualitative, nuanced account of the data at hand by identifying codes (or “themes”) and synthesizing patterns observed across the data. Using this approach, the process of reviewing codes for reliability occurs either through (1) repeated review and triangulation as a solo researcher or through (2) repeated review, discussion, and consensus forming as a research team. We followed the second, where the first and second authors discussed the findings, and the research team as a whole reviewed drafts of themes identified by the first author. As a result, all of the themes identified were agreed upon by the research team and reviewed by multiple individuals.

The first author read through the corpus of focus group notes to generate an initial list of codes (e.g., the need for language accessibility in educational materials, sources of misinformation exposure, strategies for discussing misinformation with community members) that were iteratively reviewed and discussed as a team. Using these codes, we created a series of research analysis memos, including a data matrix, synthesizing core findings from the coding and corpus review process to guide our analysis of our qualitative findings (Miles et al., 2018). The data matrix is a strategy often used in qualitative research to describe data at the group level (i.e., across focus groups and across organizations) to reveal higher-level patterns in the data. We organized the findings from our focus groups by organization (MFV, AAAJ, NAN, and NCAI) and by theme (i.e., sources of information, sources of trusted information). Using this matrix, we were able to systematically examine how the leaders of four different community organizations—MFV, AAAJ, NAN, and NCAI—experienced the problem of misinformation within their communities and the principles underlying their proposed solutions.

Conclusion

We identified several pathways through which misinformation prevention efforts can be more equitable and effective. Building from our findings, we illustrate how practitioners, academics, and policymakers can better address the misinformation crisis within communities of color by proposing actionable steps to make misinformation interventions more inclusive, and by providing examples from a series of co-designed workshops.

First, future interventions should focus on translating educational resources into multiple languages to account for language diversity within and across communities of color. Second, initiatives focusing on the spread of misinformation online should account for the nuances of ethnic media ecologies by collaborating with trusted messengers within diasporic social media groups (e.g., Black Twitter) and ethnic media outlets (e.g., Indian Country Today) to increase access to trustworthy information and debunk false information. Third, messaging around countering misinformation narratives should acknowledge the role of historical and ongoing injustices against communities of color in perpetuating distrust of political and health institutions, and center empathetic approaches to hearing individuals’ concerns.

Topics

Bibliography

Aspen Institute. (2021, November). Commission on Information Disorder final report. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Aspen-Institute_Commission-on-Information-Disorder_Final-Report.pdf

Andrasfay, T., & Goldman, N. (2021). Reductions in 2020 US life expectancy due to COVID-19 and the disproportionate impact on the Black and Latino populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(5), e2014746118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2014746118

Asian American Disinformation Table. (2022). Power, platforms, politics: Asian Americans and disinformation landscape report. https://www.asianamdisinfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AsianAmDisinformation_LandscapeReport2022.pdf

Baciu, A., Negussie, Y., Geller, A., Weinstein, J. N., & National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). The state of health disparities in the United States. In J. N. Weinstein, A. Gellar, Y. Negussie, & A. Baciu, Eds., Communities in action: Pathways to health equity (pp. 57–88). The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24624

Badrinathan, S. (2021). Educative interventions to combat misinformation: Evidence from a field experiment in India. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1325–1341. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000459

Basol, M., Roozenbeek, J., Berriche, M., Uenal, F., McClanahan, W. P., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Towards psychological herd immunity: Cross-cultural evidence for two prebunking interventions against COVID-19 misinformation. Big Data & Society, 8(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211013868

Batailler, C., Brannon, S. M., Teas, P. E., & Gawronski, B. (2022). A signal detection approach to understanding the identification of fake news. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 78–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620986135

Beers, A., Wilson, T., & Starbird, K. (2022). The demographics of an international influence operation affecting Facebook users in the United States. Journal of Online Trust and Safety, 1(4). https://doi.org/10.54501/jots.v1i4.55

boyd, danah. (2018, March). You think you want media literacy… do you? Data & Society: Points. https://points.datasociety.net/you-think-you-want-media-literacy-do-you-7cad6af18ec2

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Wineburg, S., Rapaport, A., Carle, J., Garland, M., & Saavedra, A. (2021). Students’ civic online reasoning: A national portrait. Educational Researcher, 50(8), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211017495

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Ziv, N., & Wineburg, S. (2022). Civic preparation for the digital age: How college students evaluate online sources about social and political Issues. The Journal of Higher Education, 93(7), 963–988. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2022.2082783

Cortina, J. & Rottinghaus, B. (2022, February 25). With the 2022 midterms ahead, expect another Latino misinformation crisis. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/02/25/latino-misinformation-spanish-social-media/

Chu, S. K. W., Xie, R., & Wang, Y. (2021). Cross-language fake news detection. Data and Information Management, 5(1), 100–109. https://doi.org/10.2478/dim-2020-0025

Delcker, J., Wanat, Z., & Scott, M. (2020). The coronavirus fake news pandemic sweeping WhatsApp. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/16/coronavirus-fake-news-pandemic-133447

Diamond, L. L., Batan, H., Anderson, J., & Palen, L. (2022, April). The polyvocality of online COVID-19 vaccine narratives that invoke medical racism. In CHI ’22: Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–21). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491102.3501892

Dodson, K., Mason, J., & Smith, R. (2021, October 13). Covid-19 vaccine misinformation and narratives surrounding Black communities on social media. First Draft News. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/covid-19-vaccine-misinformation-black-communities/

Freelon, D., Bossetta, M., Wells, C., Lukito, J., Xia, Y., & Adams, K. (2020). Black trolls matter: Racial and ideological asymmetries in social media disinformation. Social Science Computer Review, 40(3), 560–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320914853

Gallon, K. (2020, October 7). The Black press and disinformation on Facebook. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/the-black-press-and-disinformation-on-facebook/

Getahun, H. (2021, November 10). COVID misinformation plagues California’s Indigenous speakers. CalMatters. https://calmatters.org/health/coronavirus/2021/11/covid-indigenous-language-barriers/

Goodman, B. (2021). Lost in translation: Language barriers hinder vaccine access. MedScape. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/949901

Hill, L. & Artiga, S. (2022, February 22). COVID-19 cases and deaths by race/ethnicity: Current data and changes over time. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-cases-and-deaths-by-race-ethnicity-current-data-and-changes-over-time/

Howe, J. L., Young, C. R., Parau, C. A., Trafton, J. G., & Ratwani, R. M. (2021). Accessibility and usability of state health department COVID-19 vaccine websites: A qualitative study. JAMA Network Open, 4(5), e2114861. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14861

Kretzmann, J., & McKnight, J. P. (1996). Assets-based community development. National Civic Review, 85(4), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncr.4100850405

Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Ecker, U. K. H., Albarracín, D., Amazeen, M. A., Kendeou, P., Lombardi, D., Newman, E. J., Pennycook, G., Porter, E. Rand, D. G., Rapp, D. N., Reifler, J., Roozenbeek, J., Schmid, P., Seifert, C. M., Sinatra, G. M., Swire-Thompson, B., van der Linden, S., Vraga, E. K., Wood, T. J., & Zaragoza, M. S. (2020). The debunking handbook 2020. George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication. http://doi.org/10.17910/b7.1182

Longoria, J., Acosta, D., Urbani, S., & Smith, R. (2021). A limiting lens: How vaccine misinformation has influenced Hispanic conversations online. First Draft News. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/covid19-vaccine-misinformation-hispanic-latinx-social-media/

Lu, Y., Schaefer, J., Park, K., Joo, J., & Pan, J. (2022). How information flows from the world to China. The International Journal of Press/Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612221117470

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2018). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Sage.

Mochkofsky, G. (2022, January 14). The Latinx community and COVID-disinformation campaigns. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/the-latinx-community-and-covid-disinformation-campaigns

Moore, R. C., Dahlke, R., & Hancock, J. T. (2022). Exposure to untrustworthy websites in the 2020 US election. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/6bgqh

Moore, R. C., & Hancock, J. T. (2022). A digital media literacy intervention for older adults improves resilience to fake news. Scientific Reports, 12, 6008. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08437-0

Navia, T. (2021, November 24). COVID misinformation is running rampant online, and it’s worse in Spanish. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/jgm8z8/covid-misinformation-is-running-rampant-online-and-its-worse-in-spanish

Nguyen, A., & Catalan-Matamoros, D. (2020). Digital mis/disinformation and public engagement with health and science controversies: Fresh perspectives from Covid-19. Media and Communication, 8(2), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i2.3352

Nguyễn, S., Kuo, R., Reddi, M., Li, L., & Moran, R. E. (2022). Studying mis- and disinformation in Asian diasporic communities: The need for critical transnational research beyond Anglocentrism. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-95

Saltz, E., Barari, S., Leibowicz, C., & Wardle, C. (2021). Misinformation interventions are common, divisive, and poorly understood. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(5). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-81

Seitz, A., & Weissert, W. (2021, December 1). Inside the ‘big wave’ of misinformation targeted at Latinos. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/latinos-misinformation-election-334d779a4ec41aa0eef9ea80636f9595

Starbird, K., Arif, A., & Wilson, T. (2019). Disinformation as collaborative work: Surfacing the participatory nature of strategic information operations. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359229

Soto-Vásquez, A. D., Gonzalez, A. A., Shi, W., Garcia, N., & Hernandez, J. (2021). COVID-19: Contextualizing misinformation flows in a US Latinx border community (media and communication during COVID-19). Howard Journal of Communications, 32(5), 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2020.1860839

Walther, B., Hanewinkel, R., & Morgenstern, M. (2014). Effects of a brief school-based media literacy intervention on digital media use in adolescents: Cluster randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(9), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0173

Wilson, T., & Starbird, K. (2020). Cross-platform disinformation campaigns: Lessons learned and next steps. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-002

Wineburg, S., Breakstone, J., McGrew, S., Smith, M. D., & Ortega, T. (2022). Lateral reading on the open Internet: A district-wide field study in high school government classes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(5), 893–909. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000740

Wineburg, S., & McGrew, S. (2019). Lateral reading and the nature of expertise: Reading less and learning more when evaluating digital information. Teachers College Record, 121(11). https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811912101102

Zhang, C. (2017). How misinformation spreads on WeChat. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center/wechat-misinformation-china.php

Funding

The research was supported by funding from Stanford Social Impact Labs. Angela Y. Lee and Ryan C. Moore are supported by Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowships.

Competing Interests

We have no conflicts of interests to report.

Ethics

The data and analysis involved in this study did not require IRB review per our institution’s guidelines. While the data collected were classified as “research,” they were not considered “human subjects research” because the data were (1) de-identified and (2) the research team did not interact with any participants directly as we obtained the fully anonymized, de-identified transcript data from PEN facilitators. All names and potentially identifying information (e.g., ages, gender) were removed prior to analysis. These data were in line with the guideline that non-human subjects research that does not require IRB review includes, “data or specimens when no access to the code or link could allow identification of the individual.” Ethnicity and gender were self-reported by participants in their own words.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our collaborators and community partners for making this research possible. We thank the PEN America Knowing the News team, including Summer Lopez, Hannah Waltz, Damaso Reyes, James Bailey, and Ernest Niño-Murcia. Special thanks to our featured presenters: Dr. Olveen Carrasquillo (MFV), Angelica Razo (MFV), Dr. Siobhan Wescott (NCAI), Dr. Aaron Payment (NCAI), Cookie Duong (AAAJ), Dr. Rupali Limaye (AAAJ), and Dr. Melissa Clarke (NAN). Finally, we are grateful to the members of the Stanford Social Media Lab, namely Sunny Liu, Alicia Purpur, and Cassia Reddig for assisting with this project.