Peer Reviewed

The Twitter origins and evolution of the COVID-19 “plandemic” conspiracy theory

Article Metrics

48

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Tweets about “plandemic” (e.g., #plandemic)—the notion that the COVID-19 pandemic was planned or fraudulent—helped to spread several distinct conspiracy theories related to COVID-19. But the term’s catchy nature attracted attention from anti-vaccine activist filmmakers who ultimately created Plandemic the 26-minute documentary. Plandemic falsely attacks NIAID Director Dr. Anthony Fauci, among others, and an eventual coronavirus vaccine. The film, which has since been widely discredited, appeared to at least temporarily shift Twitter communications to different topics and organizations, fueling the flow of conspiracy theories and misinformation itself with specific public figures to demonize.

Research Questions

- How did the May 2020 release of the documentary Plandemic change ongoing Twitter discourse mentioning the term “plandemic”?

- What are the characteristics of “plandemic” tweets before versus after the film?

- Which tweet characteristics are associated with more likes and retweets before versus after the film?

Essay Summary

- On May 4th, 2020 the first half of the documentary Plandemic was released and rapidly spread via social media by leveraging pre-existing cynicism about COVID-19. Given heightened global attention on preventing the spread of coronavirus and treating COVID-19, misinformation about the origins of the virus and how to stop it warrant immediate attention, so as to protect public health.

- Prior to May 4th, “plandemic” (e.g., #plandemic, planDEMic) was a frequently used social media term associated with several popular conspiracy theories. By harnessing a pre-existing social media term/hashtag, the film’s producers and promotoers had access to captive online networks of conspiracy theory believers through which to initiate the distribution of the documentary.

- We collected 84,884 publicly accessible tweets mentioning “plandemic” between January 24th (first mention on Twitter) and May 17th (two weeks after the film’s May 4th online release). The content and popularity of tweets were analyzed before and after the documentary’s release.

- Twitter discourse mentioning “plandemic” spiked after the film’s release but receded to observed pre-film levels within a 2-week post-film period. Specifically, vaccine-related tweets were relatively marginal and unaltered by the film’s release. In addition, the film increased attention towards certain political, public health, media organizations, and perceived elite public figures. Discourse about freedoms and liberties also increased after the film’s release.

- Future research must explore underlying drivers of anti-science and anti-evidence sentiment by learning about the priorities and health beliefs of people who subscribe to conspiracy theories like the plandemic conspiracy theory and are influenced by and share similar misinformation. Public health advocates and health educators must also participate through preventive interventions and campaigns.

Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in hundreds of thousands of lives lost globally. It has also facilitated the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories at a scale and pace that is unprecedented (Cuan-Baltazar et al., 2020; Fisher, 2020), leading many to refer to this mis- and disinformation crisis as a “misinfodemic”, defined as the “viral spread of false information” (McGinty & Gyenes, 2020). COVID-19 conspiracy theories have arisen from the fringes of social media conversations to discussions on mainstream media (Ahmed et al., 2020; Uscinski et al., 2020). Understanding the origins, motivations, and evolution of viral misinformation is a key function of social media surveillance, and timely research is needed to combat misinformation’s spread (Ahmed et al., 2020; Y. K. Chang et al., 2020; Chou et al., 2018). In the current study, we analyzed Twitter posts about the plandemic conspiracy theory (i.e., planned epidemic) as a case study for the emergence, evolution, and dynamism of COVID-19 misinformation specifically, and social media misinformation in general. We identify next steps with applications at multiple levels including for researchers, public health practitioners, and social media platforms.

The Plandemic conspiracy theory

On May 4th, 2020, the 26-minute film Plandemic (“the film”, “the documentary”) was released online and shared via Twitter, YouTube, and other social media platforms (Andrews, 2020; Shepherd, 2020). Prior to May 4th, “plandemic” was a frequently used social media term and hashtag associated with several popular conspiracy theories, the general gist of most being that the pandemic was fake (i.e., virus does not exist) or human-made. Driven by expert-like testimony and deliberately “viral […] shocking and conspiratorial” branding (Rottenberg & Perman, 2020), the documentary leveraged underlying beliefs about COVID-19 and anti-containment sentiments and diverted viewers towards anti-vaccine behaviors and general questioning the pandemic’s impact on our freedoms and liberties (Frenkel et al., 2020). Specifically, the documentary aimed to expose baseless accusations of corruption (Alba, 2020) among key experts in the pandemic response (e.g., Dr. Anthony Fauci) while also suggesting broader collusion among politicians (e.g., Barack Obama) and global elite (e.g., Bill Gates). In other words, the film politicized and demonized public health figures combatting the pandemic. The film’s rapid spread was facilitated by pre-existing social media networks, such as Facebook groups and viral hashtags (Frenkel et al., 2020). Uniting disparate fringe-belief groups is a common tactic among vaccine opponents (Kata, 2012).

Throughout Plandemic, discredited former National Cancer Institute scientist Dr. Judy Mikovits is shown in a series of interview clips (Alba, 2020). Dr. Mikovits makes several demonstrably false or misleading claims about COVID-19, including: 1) coronavirus may have originated from US government research into the flu vaccine, 2) COVID-19 vaccine is being used to push a pro-vaccine agenda led by academia and industry, 3) Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease, profited from the HIV/AIDS epidemic and suppressed Dr. Mikovits’ anti-vaccine research, and 4) face masks activate dormant coronavirus particles implanted through flu vaccination (Alba, 2020; Elliott, 2020; Frenkel et al., 2020; Funke, 2020a). By May 7th, 2020 the film was removed from YouTube because it contradicted World Health Organization guidance, a platform policy violation, and nearly all other social media platforms subsequently blocked the film (Lapin, 2020). On August 18th, 2020, a 75-minute second half of Plandemic was released online but has failed to garner similar attention as the initial release due to pre-emptive actions by online platforms (Funke, 2020b; Spencer et al., 2020).

Plandemic delegitimizes, or at least seeks to delegitimize, a vocal and needed advocate for public health risk communication about COVID-19, Dr. Anthony Fauci. In a statement to Snopes following the documentary’s release, Dr. Fauci personally refuted Dr. Mikovits’ claims (Kasprak, 2020). Nevertheless, delegitimizing visible and trusted public health leaders sows doubt in the federal government’s pandemic response as well as the safety and efficacy of an eventual coronavirus vaccine. For example, if Dr. Fauci’s character prior to the pandemic is drawn into question, as the documentary suggests, then his post-pandemic conclusions may be unduly scrutinized or even discredited. By extension then, the national shutdown and impacts of quarantine could also be blamed on Dr. Fauci’s now-disqualified conclusions. Anti-vaccine activists produced Plandemic to increase vaccine hesitancy and decrease vaccination, but their lasting impact may be that it promoted cynicism about measures meant to prevent COVID-19 spread, such as use of face masks and social distancing. Disregarding these measures threatens public health and may only serve to extend the pandemic. Stopping the spread and influence of Plandemic – and related misinformation – is in the interest of the public’s health.

Plandemic as a case study for social media misinformation

We investigated tweets about the plandemic conspiracy theory as a case study of COVID-19 social media misinformation, and provide novel and original research that complements media reports (Frenkel et al., 2020). We found that the documentary reduced the online movements’ focus on the COVID-19 pandemic as well as vaccine-related conversations. Instead, the film identified specific individuals as the new, personalized focus of anti-pandemic ire. Although conspiracy theories were common and popular both before and after the film’s release, post-documentary tweets were particularly focused on personal attacks and vilifying specific public health experts. Our findings support a pro-active, responsive, and multi-pronged effort to fight misinformation, specifically: 1) preemptively addressing misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine now 2) ongoing monitoring and surveillance of social media platforms for emerging conspiracy theories, 3) censoring, fact-checking, and debunking social media content that contains false information (i.e., misinformation, disinformation, conspiracy theories), and 4) learning about who creates misinformation and conspiracy theories and their motivations. At a minimum, social media platforms must respond to false information, and public health advocates and health educators must also participate through preventive interventions, campaigns, and research.

First, we must preemptively address misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine. A recent poll reported that half of Americans would get the coronavirus vaccine, while one in five would not get vaccinated (AP/NORC, 2020). Anti-vaccine proponents used Plandemic to sow discord with the ultimate goal of increasing vaccine hesitancy and decreasing vaccination. As the world is now waiting on a vaccine, misinformation such as that contained in Plandemic may increase hesitancy towards coronavirus vaccination (Wadman, 2020). In cases where we cannot prevent exposure to misinformation, we need to build health and media literacy skills to prevent misinformation’s influence – referred to as primary prevention in public health. Primary prevention of misinformation’s influence – pre-bunking rather than debunking – is necessary and may be accomplished through building literacy skills to discern true versus misleading or false information and develop skepticism towards newly-received information and its sources (Jolley & Douglas, 2017; Lewandowski & Cook, 2020). For example, Roozenbeek and colleagues (2020) created a social media simulation where participants acted as creators of fake news content. Playing the game increased participants’ resistance to misinformation about politics and related conspiracy theories. Within the context of COVID-19, an adapted version of the game could be created with the goal of pre-empting coronavirus vaccine misinformation. Alternatively, another option to preempt misinformation may be to produce a documentary promoting coronavirus vaccination to counter misinformation like Plandemic, which cost less than $2,000 to create (Rottenberg & Perman, 2020). Whether literacy-building content is formatted as a game or viral video, public health advocates and communications must address misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine now and consider how to effectively use pre-bunking as a mitigation strategy for misinformation’s influence among the general public (Cook et al., 2017; Jolley & Douglas, 2017; Roozenbeek et al., 2020).

Second, there must be robust systems for tracking the emergence of misinformation and conspiracy theories, including the use of both automated and manually-controlled online dashboards (Resnick et al., 2018). Twitter is a uniquely accessible source of social media data because it is open source (i.e., publicly available). While vaccine-related plandemic tweets were limited in scope overall and did not become more prevalent in the wake of the Plandemic documentary, the documentary was successful at elevating the profile of the plandemic conspiracy theory in general. Despite a surge in the number of plandemic tweets, where one may expect the average level of engagement (i.e., likes, retweets) to decrease as the amount of content increases, we found that the numbers of likes and retweets were actually unchanged pre- versus post-documentary, suggesting consistent engagement from a reliable network of Twitter users. By harnessing a term/hashtag that was already in use on social media, the film’s promoters had access to pre-existing and captive social networks through which to initiate the spread of the documentary. Online resources are emerging to investigate and track different conspiracy theories and viral misinformation related to COVID-19 (Chen et al., 2020; National Press Foundation, 2020; Nsoesie & Oladeji, 2020). Such tools support journalists as they respond in real-time to developing stories about viral misinformation, and public health researchers must adapt to evolving technologies. For example, Project RCAID (Rapid Collection Analysis Interpretation and Dissemination) is an online misinformation dashboard created through a nonprofit-private partnership (Public Good Projects & Zignal Labs, 2020) for tracking emerging coronavirus stories and narratives, as well as new hashtags, on various social media platforms. Through misinformation monitoring and surveillance, the pre-emptive verification, labelling, or even removal of false social media content may be enhanced to further prevent its spread.

Third, censoring, fact-checking, and debunking content that contains false information must take a clear and transparent strategy. Social media and coronavirus-related changes in daily media consumption have created an environment of information overload and increased the use of censoring, labeling, and verifying content by social media platforms (e.g., Twitter) and forum moderators (e.g., Reddit) (Andrews, 2020; Funke, 2020a; Hall Jamieson & Albarracín, 2020). Fact-checkers and platform administrators who verify content may be overwhelmed and unable to respond quickly to emerging misinformation, demanding innovative solutions such as volunteer fact-checkers (Kim & Walker, 2020). In addition, specific pieces of misinformation or conspiracy theories may be directly debunked/fact-checked through providing corrections and alternate explanations, and repeated exposure has been shown to increase the impact of fact-checking (Lewandowsky et al., 2012). Based on our findings, tweets about the plandemic conspiracy theory spiked post-film but receded towards pre-film volumes—future avenues of research should examine what role media fact-checking, social media platform censorship, and use of warning labels played in this trajectory.

Determining how and when to verify or remove (i.e., censor) social media content is a nuanced debate. On the one hand, removing false content early can prevent the spread of “viral” misinformation from fringe social media communities to the general public and mainstream media outlets. On the other hand, too much censorship and labelling may risk further polarization, particularly among social media platform preferences (Wellemeyer, 2020). Furthermore, removing false content from one source may only enhance its spread through other sources as more people share or seek out the removed content (Bellemare et al., 2020). To this end, we found that website links and online media sharing proliferated after the film’s release on May 4th, perhaps in response to platforms restricting and removing the film. In the absence of a comprehensive strategy, Plandemic may continue to spread through online social media, and potentially traditional media sources such as broadcast television. As recently as July of 2020, Plandemic was set to be aired on nearly 200 local US televisions stations owned by Sinclair Broadcasting Group in a since-abandoned planned broadcast (Farhi, 2020). Sinclair Broadcasting Group is a conservative media conglomerate that operates local television stations across the US, reaching approximately four in ten (39%) US television viewers (A. Chang, 2018). Taken together, our findings and the continued threat posed by Plandemic and similar misinformation support a comprehensive and truly multi-media strategy for determining when, how, why, and by whom false content is removed, labelled, or fact-checked.

Fourth, our efforts to address misinformation must understand who posts content and why. Research into cognitive biases, in particular information and confirmation biases, suggests that if someone is convinced of a certain viewpoint and encounters information that refutes their position, then that person would be unlikely to accept new information and may even attack the source of the counter information (Baron et al., 1988; Nickerson, 1998). People who believe conspiracy theories like the plandemic one, may be resistant to fact-checking and easily rationalize new information – both true and false – within the context of existing conspiracy theory beliefs (Ognyanova et al., 2020; Uscinski et al., 2020; Wood et al., 2012). Future research must seek to understand the underlying drivers of anti-science and anti-evidence sentiment by learning about the priorities and health beliefs of people who subscribe to conspiracy theories like plandemic and are influenced by similar misinformation.

Findings

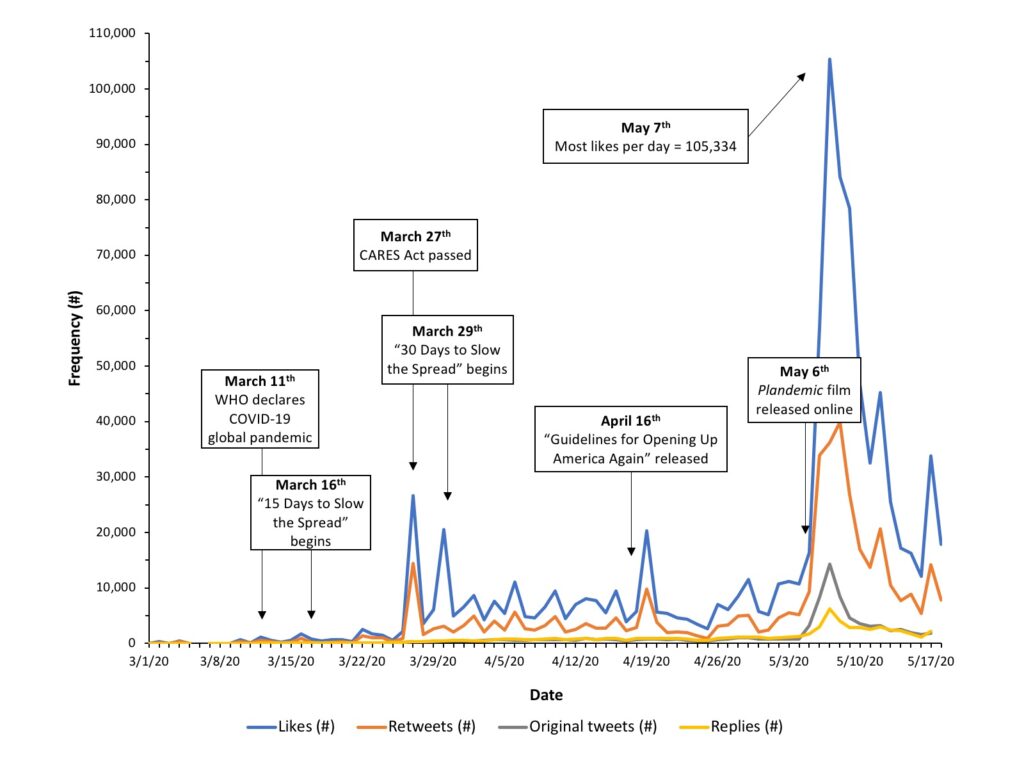

Findings are organized by research questions: all three findings address our primary research question (RQ1: How did the May 2020 release of the documentary Plandemic change ongoing Twitter discourse mentioning the term “plandemic”?); findings 2 and 3 correspond to research question 2 (RQ2: What are the characteristics of “plandemic” tweets before versus after the film?); findings 2 and 3 also correspond to research question 3 (RQ3: Which tweet characteristics are associated with more likes and retweets before versus after the film?). Figure 1 presents a timeline of the volume of original tweets, retweets, replies, and likes related to the use of plandemic on Twitter. All results tables are included in Appendix A.

Finding 1: Twitter discourse about the film spiked and quickly fell off after the Plandemic’s release.

The film created a surge of new content. More than twice as many tweets were created in the 14 days following the documentary’s release compared to the previous 100 days (see Figure 1). As shown in the examples provided in Table A2 (see Appendix A), the film was first mentioned on May 4th, 2020, but the term “plandemic” was used on Twitter as early as January 24th, 2020. An average of 1,246 tweets per day mentioned plandemic, and the average number of tweets per day increased more than 10-fold from 612 pre-film to 10,657 post-film. The average number of followers per user more than tripled following the film’s release (see Appendix A, Table A1). No significant change was observed in the average numbers of likes and retweets, suggesting a similar level of user engagement before and after the film across a larger overall volume of plandemic tweets.

Links and online media sharing proliferated after May 4th, perhaps in response to platforms restricting and removing the film. In general, most tweets (58%) were related to online information; nearly half (45%) promoted sharing media, and fewer discussed information censorship (3%) or were about false information (4%) (see Appendix A, Table A3). Percentage of tweets that shared online media nearly tripled from 20% pre-film to 56% post-film, while censorship mentions increased five-fold. Terms used to describe false information nearly doubled after Plandemic (see Appendix A, Table A3). Tweets mentioning online information received more retweets and likes following Plandemic’s release (see Appendix A, Table A3).

Finding 2: Anti-government and largely anti-liberal political conspiracy theory tweets were common and popular both before and after the film’s release, and tweets were often directed towards conservative media and political figures through mentions and replies.

A third of tweets (30%) discussed at least one conspiracy theory genre. The most common conspiracy theories were about the deep state government (17%), nefarious cover-ups (13%), anti-vaccination (8%), Bill Gates (6%), and 5G wireless technology (2%) (see Appendix A, Table A3). Tweets about nefarious cover-up conspiracy theories increased in volume post-documentary, whereas other conspiracy theory categories decreased significantly. Politics and government and the media were mentioned less frequently (15% and 2%, respectively) (see Appendix A, Table A3). The three most frequently mentioned political or government officials were current US President Donald Trump (8%), NIAID Director Anthony Fauci (7%), and former US President Barack Obama (2%).

Liberal politics were discussed nearly ten times more often than conservative politics (7% liberal versus <1% conservative, respectively) (see Appendix A, Table A3). Conversely, conservative media and political figures were often targeted through user mentions and replies to recent tweets. Reply tweets were most frequently addressed towards the following users: 1) @RealDonaldTrump, 2) @IngrahamAngle (Fox News host), 3) @RealJamesWoods (conservative American actor; 0.47%), 4) @GregGutfeld (Fox News host), 5) @Mitchellvii (conservative American radio host), 6) @BillGates, and 7) @DrJudyAMikovits (Plandemic documentary).

Finding 3: On Twitter, the film turned attention to certain public figures and the pandemic’s impact on freedoms and liberties, but vaccine-related tweets were relatively marginal and unaltered by the film.

Before the film, the term “plandemic” was associated with a range of conspiracy theories about the “deep state,” Bill Gates, and the pro-vaccine agenda, and President Trump and the political left were most frequently mentioned (see examples tweets in Appendix A, Table A1). After the film was released, the conversation changed decidedly both in terms of the type of content being produced and what content was receiving the most engagement from other Twitter users (see Appendix A, Tables A3 and A4). Tweets in our sample created after the film’s release were less likely to discuss COVID-19 than posts from before (see Appendix A, Table A3). COVID-19’s impact on freedoms and liberties was mentioned significantly more often and received more likes and retweets post-documentary. Anti-vaccine tweets appear to be limited and not changed in the documentary’s wake. Despite an observed decrease in overall tweets about vaccination in our sample, vaccine-related tweets were retweeted and liked more following the documentary’s release (see Appendix A, Tables A3 and A4).

The film polarized Twitter use of plandemic resulting in increased attention towards Barack Obama and Dr. Anthony Fauci. Significant increases in retweets and likes were observed among tweets mentioning former President Barack Obama (770%), NIAID Director Dr. Anthony Fauci (45%), and Bill Gates (42%) (see Appendix A, Tables A3 and A4). Current US President Donald Trump was the most mentioned person in tweets about plandemic, but tweets mentioning Trump decreased significantly after the documentary’s release (see Appendix A, Table A3). Tweets mentioning current President Donald Trump received more retweets before the documentary than afterward (see Appendix A, Table A4). Percentage of tweets discussing mainstream media increased significantly after the film’s release, and tweets about alternate media significantly decreased in volume (see Appendix A, Table A3).

Methods

A retrospective analysis of tweets mentioning “plandemic” was conducted to address our stated research questions. Our study of original tweets mentioning “plandemic” before and after Plandemic’s release provides descriptive and correlational findings that address current infodemiological needs. The term “plandemic” was our search criteria and therefore refers to all eligible analyze tweets (i.e., all tweets contained the keyword “plandemic”). The study dataset comprised 84,884 original tweets mentioning plandemic from 51,021 Twitter users. Original tweets were liked or shared 1,286,062 times (likes=893,299; retweets=392,763) by other users and could have reached a minimum of 819,112,285 followers.

Data collection and sampling

Using the “twitter2stata” package in Stata/IC 15.1 software, we downloaded all publicly-accessible tweets (N=545,054) mentioning plandemic between January 24th (first mention on Twitter) and May 17th (two weeks [14 days] after the film’s May 4th online release). Tweets were collected at least once daily depending on the rate limit maximum of 18,000 tweets. We modified code in Stata/IC 15 to collect tweets based on their sequential unique IDs (e.g., 1220727066599010304). Nevertheless, some relevant tweets may not have been captured through this data collection strategy, particularly during period when tweet volume was highest, and this could reduce the transferability of our findings about all plandemic tweets. When the maximum limit was reached, multiple subsequent searches were conducted to reduce the number of tweets that may be missed, such every four hours.

To allow for comparison pre- and post-film, we ended data collection two weeks following the film’s release. The dataset included original tweets (n=84,884), retweets (n=392,964), and tweets that were replies to other tweets (“replies”; n=67,206). Our main analysis of text terms and topics (see example terms in Appendix B, Table B1) includes only original tweets mentioning plandemic because we want to understand unsolicited and unprompted Twitter content. Only English-language terms were used throughout our analysis because Twitter API defaults to English-language tweets. We also did not identify any tweets in languages besides English. We compared all analyses and results before and after the film’s release on May 4th, 2020. All statistical analyses and data management were conducted in Stata/IC 15 software.

Data analysis

To answer RQ1 (How did the May 2020 release of the documentary Plandemic change ongoing Twitter discourse mentioning the term plandemic?), Pearson chi-squared tests and unpaired t-tests assessed significant differences in tweet and user metadata characteristics (see Appendix A, Table A1), as well as in text topic categories (see Appendix A, Table A3). We also calculated percent change (D) in average engagement (i.e., likes + retweets) and assessed significant differences using unpaired t-tests (see Appendix A, Table A4).

To answer RQ2 (What are the characteristics of plandemic tweets before versus after the film?), we described the terms (i.e., hashtags, users, topics) mentioned most frequently in original tweets and conducted a summative content analysis utilizing automated text analysis and topic modeling methods. Detailed information about our content analysis process, including a table of relevant text terms (see Table B1), can be found in Appendix B.

To answer RQ3 (Which tweet characteristics are associated with more likes and retweets before versus after the film?), we evaluated differences in proxy measures for reach and popularity. All topic indicators were non-mutually exclusive independent variables. Reach and popularity, the dependent variables, were operationalized by the number of retweets and number of likes, respectively. As both likes and retweets are measures of a tweet’s popularity and potential exposure to Twitter followers and other social networks, we aggregated total likes and retweets for each original tweet, creating a pooled measure of audience engagement (see Appendix A, Table A4).

Topics

Bibliography

Ahmed, W., Vidal-Alaball, J., Downing, J., & Seguí, F. L. (2020). COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: Social network analysis of Twitter data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(5), e19458. https://doi.org/10.2196/19458

Alba, D. (2020, May 9). Virus conspiracists elevate a new champion. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/09/technology/plandemic-judy-mikovitz-coronavirus-disinformation.html

Andrews, T. (2020, May 7). “Plandemic” conspiracy video removed by Facebook, YouTube and Vimeo. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/05/07/plandemic-youtube-facebook-vimeo-remove/

AP/NORC. (2020). Expectations for a COVID-19 vaccine. The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. http://www.apnorc.org:80/projects/Pages/Expectations-for-a-COVID-19-Vaccine.aspx

Baron, J., Beattie, J., & Hershey, J. C. (1988). Heuristics and biases in diagnostic reasoning: II. Congruence, information, and certainty. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 42(1), 88–110.

Bellemare, A., Nicholson, K., & Ho, J. (2020, May 21). How a debunked COVID-19 video kept spreading after Facebook and YouTube took it down. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/alt-tech-platforms-resurface-plandemic-1.5577013

Chang, A. (2018, April 6). Sinclair’s takeover of local news, in one striking map. Vox.https://www.vox.com/2018/4/6/17202824/sinclair-tribune-map

Chang, Y. K., Literat, I., Price, C., Eisman, J. I., Gardner, J., Chapman, A., & Truss, A. (2020). News literacy education in a polarized political climate: How games can teach youth to spot misinformation. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-020

Chen, E., Lerman, K., & Ferrara, E. (2020). Tracking social media discourse about the COVID-19 pandemic: Development of a public coronavirus Twitter data set. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e19273. https://doi.org/10.2196/19273

Chou, W.-Y. S., Oh, A., & Klein, W. M. P. (2018). Addressing health-related misinformation on social media. JAMA, 320(23), 2417–2418. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.16865

Cook, J., Lewandowsky, S., & Ecker, U. K. H. (2017). Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PLoS ONE, 12(5), e0175799. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175799

Cuan-Baltazar, J. Y., Muñoz-Perez, M. J., Robledo-Vega, C., Pérez-Zepeda, M. F., & Soto-Vega, E. (2020). Misinformation of COVID-19 on the Internet: Infodemiology study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e18444. https://doi.org/10.2196/18444

Elliott, J. K. (2020, May 11). Viral ‘Plandemic’ clip pushes wild claims about coronavirus, masks and vaccines—National. GlobalNews. https://globalnews.ca/news/6928827/coronavirus-plandemic-judy-mikovits/

Farhi, P. (2020, July 31). Sinclair yanked a pandemic conspiracy theory program. But it has stayed in line with Trump on coronavirus. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/media/sinclair-yanked-a-pandemic-conspiracy-theory-program-but-it-has-stayed-in-line-with-trump-on-coronavirus/2020/07/31/5d90a296-d021-11ea-8c55-61e7fa5e82ab_story.html

Fisher, M. (2020, April 8). Why coronavirus conspiracy theories flourish. And why it matters. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/world/europe/coronavirus-conspiracy-theories.html

Frenkel, S., Decker, B., & Alba, D. (2020). How the ‘Plandemic’ movie and its falsehoods spread widely online. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/20/technology/plandemic-movie-youtube-facebook-coronavirus.html

Funke, D. (2020a, May 7). Fact-checking ‘Plandemic’: A documentary full of false conspiracy theories about the coronavirus.PolitiFact. https://www.politifact.com/article/2020/may/08/fact-checking-plandemic-documentary-full-false-con/

Funke, D. (2020b, August 18). Fact-checking ‘Plandemic 2’: Another video full of conspiracy theories about COVID-19. PolitiFact. https://www.politifact.com/article/2020/aug/18/fact-checking-plandemic-2-video-recycles-inaccurat/

Hall Jamieson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2020). The Relation between media consumption and misinformation at the outset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the US. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-012

Jolley, D., & Douglas, K. M. (2017). Prevention is better than cure: Addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47(8), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12453

Kasprak, A. (2020, May 6). Was a scientist jailed after discovering a deadly virus delivered through vaccines? Snopes. https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/scientist-vaccine-jailed/

Kata, A. (2012). Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm–An overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine, 30(25), 3778–3789.

Kim, H., & Walker, D. (2020). Leveraging volunteer fact checking to identify misinformation about COVID-19 in social media. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-021

Lapin, T. (2020, May 8). Social media networks scrambling to remove viral ‘Plandemic’ conspiracy video. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/05/07/social-media-networks-scrambling-to-remove-viral-conspiracy-video/

Lewandowski, S., & Cook, J. (2020). The conspiracy theory handbook. Center for Climate Change Communication. Fairfax: George Mason University.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. JSTOR.

McGinty, M., & Gyenes, N. (2020). A dangerous misinfodemic spreads alongside the SARS-COV-2 pandemic. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(3). https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/a-misinfodemic-as-dangerous-as-sars-cov-2-pandemic-itself/

National Press Foundation. (2020). COVID-19 misinformation: Digital tools and journalistic quandaries. Resources Page. https://nationalpress.org/topic/covid-19-misinformation-digital-tools-and-journalistic-quandaries/

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

Nsoesie, E. O., & Oladeji, O. (2020). Identifying patterns to prevent the spread of misinformation during epidemics. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-014

Ognyanova, K., Lazer, D., Robertson, R. E., & Wilson, C. (2020). Misinformation in action: Fake news exposure is linked to lower trust in media, higher trust in government when your side is in power. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-024

Public Good Projects, & Zignal Labs. (2020). Dashboard | RCAID. https://zign.al/7nt9v

Resnick, P., Ovadya, A., & Gilchrist, G. (2018). Iffy quotient: A platform health metric for misinformation. Center for Social Media Responsibility, 17.

Roozenbeek, J., Linden, S. van der, & Nygren, T. (2020). Prebunking interventions based on “inoculation” theory can reduce susceptibility to misinformation across cultures. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(2).https://doi.org/10.37016//mr-2020-008

Rottenberg, J., & Perman, S. (2020, May 13). Meet the Ojai dad who made the most notorious piece of coronavirus disinformation yet. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/movies/story/2020-05-13/plandemic-coronavirus-documentary-director-mikki-willis-mikovits

Shepherd, M. (2020, May 7). Why people cling to conspiracy theories like ‘Plandemic.’ Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/marshallshepherd/2020/05/07/why-people-cling-to-conspiracy-theories-like-plandemic/#698c3eb95049

Spencer, S. H., McDonald, J., & Fichera, A. (2020, August 21). New “Plandemic” video peddles misinformation, conspiracies. FactCheck.Org. https://www.factcheck.org/2020/08/new-plandemic-video-peddles-misinformation-conspiracies/

Uscinski, J. E., Enders, A. M., Klofstad, C., Seelig, M., Funchion, J., Everett, C., Wuchty, S., Premaratne, K., & Murthi, M. (2020). Why do people believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories? Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-015

Wadman, M. (2020, June 5). Abortion opponents protest COVID-19 vaccines’ use of fetal cells. Science. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/06/abortion-opponents-protest-covid-19-vaccines-use-fetal-cells

Wellemeyer, J. (2020, July 3). Conservatives are flocking to a new “free speech” social media app that has started banning liberal users. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/conservatives-flock-free-speech-social-media-app-which-has-started-n1232844

Wood, M. J., Douglas, K. M., & Sutton, R. M. (2012). Dead and alive: Beliefs in contradictory conspiracy theories. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(6), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611434786

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing Interests

No conflicts of interest to report.

Ethics

A letter of determination of non-human subjects research was submitted to and accepted by the university’s institutional review board.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All applicable de-identified data and code are available via the Harvard Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PN7UPO.