Peer Reviewed

User experiences and needs when responding to misinformation on social media

Article Metrics

7

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

This study examines the experiences of those who participate in bottom-up user-led responses to misinformation on social media and outlines how they can be better supported via software tools. Findings show that users desire support tools designed to minimize time and effort in identifying misinformation and provide tailored suggestions for crafting responses to misinformation that account for emotional and relational context. Academics and practitioners interested in designing misinformation interventions that harness user participation can draw upon these findings.

Research Questions

- RQ1: What barriers or challenges do people face in identifying and responding to misinformation posted on social media?

- RQ2: What design principles should inform tools or resources that support people in identifying and responding to misinformation posted on social media?

Research note Summary

- This study relies on two phases of semi-structured interviews with 29 participants, including misinformation research experts, online community moderators, and people who respond to misinformation on social media as part of their work.

- Participants highlighted the time and effort needed to conduct research to evaluate the credibility of information and craft responses to misinformation. They also underscored the emotional labor involved in responding as they regulate their emotions to avoid conflicts and relational strife.

- To mitigate the labor involved, participants desire tools that minimize time and effort in identifying misinformation. To support crafting of responses, they want tailored suggestions that account for emotional and relational context while still providing autonomy to craft an individualized response.

- This study presents useful insights for those designing support tools to address misinformation on social media. Findings suggest that these tools will need to strike a balance between automated processes that cut down on user time and effort and preserving user autonomy.

Implications

Misinformation, typically defined as “constituting a claim that contradicts or distorts common understandings of verifiable facts” (Guess & Lyons, 2020, p. 10), is an issue of great concern, especially on social media (Lewandowsky et al., 2012; Rossini et al., 2021; Wittenberg et al., 2020). In the fight against misinformation, the role of social media platforms has received significant attention. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter have deployed a variety of misinformation interventions, including the removal of accounts and pages that share misinformation, down-ranking of pages, groups, and content associated with misinformation, warning labels and/or contextual information on posts containing misleading information, and nudges for users to read articles before posting links (Reuters, 2021; Roth & Pickles, 2020; Silverman, 2019). However, platform-based interventions can only do so much. Attempting outright removal of all misinformation, much of which may be harmless, difficult to interpret, or still evolving, is a daunting task for platforms and may be perceived as excessive censorship by users (Vogels et al., 2020). The same may be the case for the more opaque intervention of down-ranking, which involves reducing the visibility of misinformation (Gillespie, 2022). This has led to accusations of “shadow-banning” (Savolainen, 2022), which may further users’ mistrust of platforms. And when it comes to platform-provided labels, many users do not understand them or trust them either (Saltz et al., 2021). These labels are also absent in more private and encrypted online spaces like messaging apps (Malhotra, 2020).

These issues may explain why, compared to these platform-led interventions, social media users rely in large part on other users (e.g., via comment threads) and interpersonal connections while assessing potential misinformation (Geeng et al., 2020; Malhotra, 2020). In this study, we, therefore, focus on bottom-up user-led responses to misinformation. Prior research demonstrates that the efficacy of such responses is promising. People are more likely to accept misinformation corrections from those known to them compared to strangers (Margolin et al., 2018), and there is experimental evidence that observing corrective messages on social media can help to reduce misperceptions (Bode & Vraga, 2021; Vraga et al., 2020). These user-led responses may occur between family members, friends, or strangers, and may be led by professionals like health communicators and educators or supported more formally via programs or communities for crowd-sourced response (e.g., Twitter’s Birdwatch or Community Notes program, see Coleman, 2021; the Lithuanian “elves,” see Abend, 2022).

However, engaging with other users on difficult and emotionally charged topics is challenging; it requires not only identifying misinformation and researching accurate information but also responding in conversations that can turn hostile. People are often reluctant to engage in such online conversations to avoid confrontations and hurting relationships, especially when political disagreements are involved (Grevet et al., 2014).

Given these concerns, how can the power of user-led misinformation responses be better harnessed and supported? What are the barriers faced by those who participate in these efforts? We investigated these issues through semi-structured interviews with a mix of field experts and regular social media users, including people who respond to misinformation on social media as part of their professional responsibilities. We found that the process of identifying and responding to misinformation on social media involves expending labor, both in the form of time and effort and the regulation of emotions. Thus, similar to other user-led efforts like volunteer moderation on Reddit and peer production for sites like Wikipedia, user-led responses to misinformation are characterized by a significant amount of emotional labor (Dosono & Semaan, 2019; Menking & Erickson, 2015; Wohn, 2019). Here, emotional labor refers to the labor involved in regulating emotions while responding to misinformation to avoid offending others and harming existing interpersonal relationships (Feng et al., 2022; Hochschild, 2015; Malhotra & Pearce, 2022).

We believe that understanding the labor involved in identifying and responding to misinformation can help to inform the design of processes, resources, and tools to support these efforts to address misinformation. To elicit concrete design suggestions for such tools, we also presented our interview participants with a mock-up of a hypothetical response-support tool as a probe (Boehner et al., 2007). This tool was described to participants as one that could analyze social media content and provide users with information to help them gauge the content’s veracity and guide them in how to respond to misinformation in trust-building ways, informed by the user’s goals and target audience (see Appendix for more details). Participants revealed that they prefer tools that minimize the time and effort involved in identifying misinformation, especially in collecting resources that help to determine if a post contains misinformation and can be used as factual evidence while responding. Therefore, automated tools that analyze social media posts and provide users with links and evidence by potentially drawing on databases from multiple third-party fact-checking organizations may help minimize this time and effort. In terms of crafting responses, participants prefer tailored guidance informed by the emotional and relational aspects associated with responding to misinformation. They also desire autonomy in crafting responses and are reluctant to rely on boilerplate responses. Thus, future designs for support tools may include tips and guidance on how to craft responses to misinformation based on the nature of one’s relationship with the misinformation sharer. Overall, the design of support tools may, therefore, involve automated processes that help to identify misinformation and provide users with resources containing accurate information as well as a repository of human-created tips on crafting responses for different audiences that help to preserve user autonomy. Furthermore, there is potential for designs that combine automation with human feedback; for instance, large language models may be integrated into tools that allow people to get feedback on how to craft responses.

In summary, our study places the needs of social media users front and center and outlines how the design of tools to support them must be informed by these needs. While recent research has focused on the experiences of social media users in responding (or not responding) to misinformation (Feng et al., 2022; Malhotra & Pearce, 2022; Tandoc et al., 2020), our work emphasizes the labor involved in this process and also proposes concrete design suggestions for support tools. Furthermore, we identify ethical considerations associated with designing such tools. Tools that encourage people to respond to misinformation can increase their chances of encountering online harassment and hate speech, especially for those belonging to marginalized communities. Similarly, encouraging people to respond to friends or family who share misinformation carries risks because it may cause damage to the relationship. Moreover, engagement in such emotional labor may impact the mental well-being of those responding (Lee et al., 2022). Therefore, the design of these tools should support users in dealing with these emotional issues, including providing mental health resources and potentially encouraging the fostering of misinformation responder communities that provide support to each other. There are also concerns that bad actors, like those who create and spread disinformation, may weaponize such tools. While this remains a concern, it should not prevent the development of tools that support users in responding to misinformation. Indeed, as many of our interview participants noted, people who create and spread false information on social media continue to get more attention and visibility than those who attempt to identify and respond to it (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Overall, such tools would support those participating in the latter process. Finally, it is also important to acknowledge that for such tools to be widely used and accepted, people across the political spectrum will need to trust them. This remains a challenge, given that current efforts to address misinformation are equated with censorship and even face legal and political opposition in the United States (Nix et al., 2023).

Evidence

Misinformation response as labor

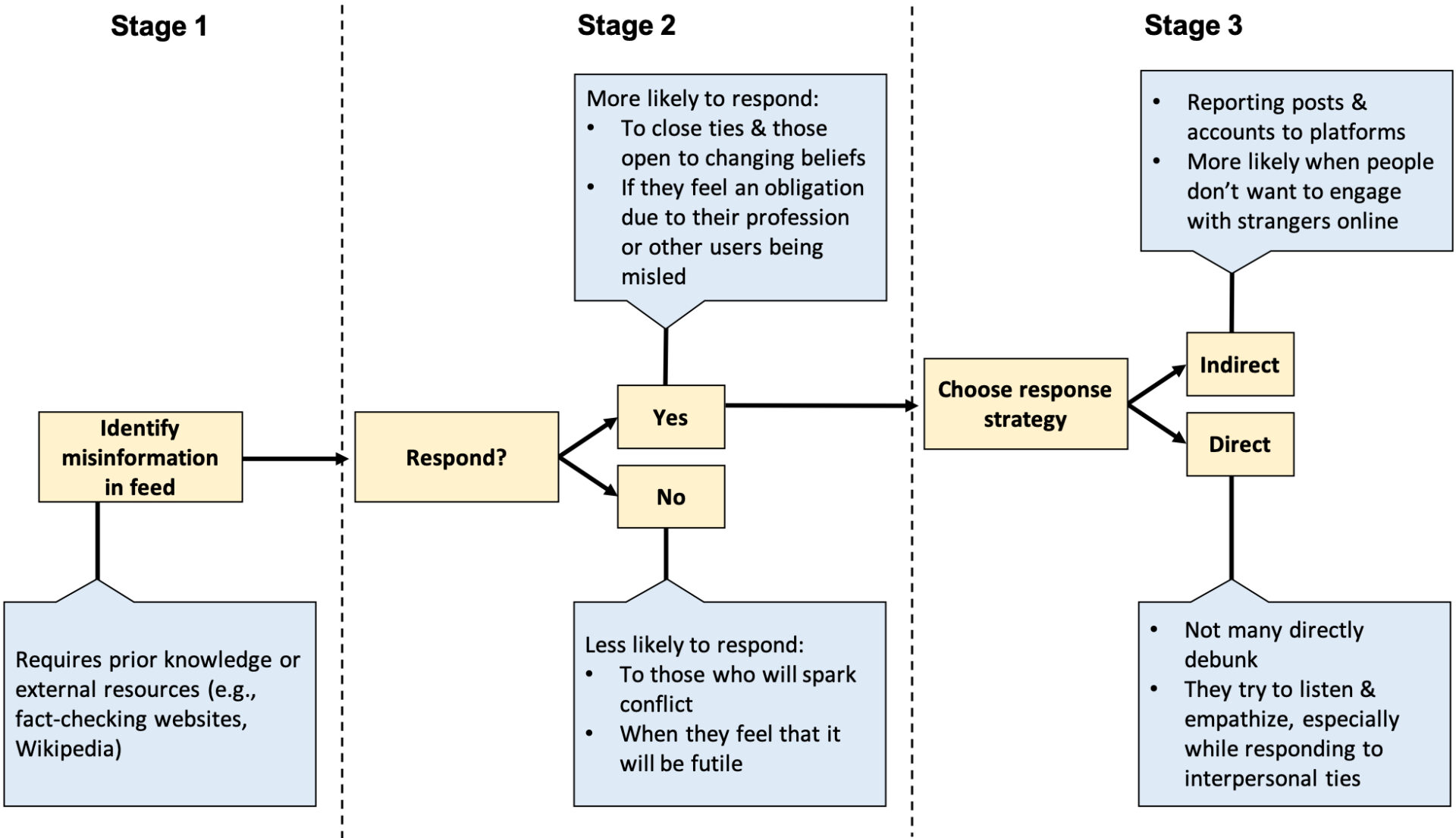

Participants described how the process of encountering and responding to misinformation online (detailed in Figure 1 below) involved a number of choices, including which resources to use to identify misinformation, whether or not to respond, and which response strategies to utilize. This echoes the extant research on people’s engagement with online misinformation mentioned above.

The participants indicated that engaging in this process was often overwhelming because it involved expending significant time and effort in conducting research to evaluate the credibility of information. As P10 said, “it’s all about finding incredible sources, incredible analysis, but also verifying using different sources.” Participants also highlighted the research involved in crafting convincing responses (e.g., “[I post] some summarized version of that [all the information collected], so that people looking at it will be like, ‘Oh, I see how it’s corrected. And that makes sense. I don’t need to look into it further.’” [P7]). Even as they engaged in such research, some participants felt like they did not have enough time and energy to address the sheer volume of misinformation online. For example, P9 said: “On the public-facing Twitter account, I have to ignore a fair amount of it because if I tried to engage everything like that that was out there, it would be an intolerable burden.” Many said that this led to them becoming wary after constantly monitoring and responding (e.g., ”I got tired of being the hall monitor, so I stopped.” [P18]).

Misinformation response as emotional labor

Participants also outlined how responding to misinformation online challenged them on an emotional level, based on their relationship with the person to whom they were responding.

Responding to strangers. Participants feared that their responses would not change the beliefs of misinformation sharers, especially if they were strangers. To convince such strangers, some expended emotional labor and tried to build a relationship with them through listening, asking questions rather than making definitive statements, and using a gentle and polite tone. P14 shared her experience: “The important part is fostering that trusted relationship … I think listening to the concerns of the person who might believe a bit of misinformation, getting them to talk out their position and just pose other questions to them [would help].” This reflects the importance of building interpersonal relationships with strangers in order to make an impact. However, this requires regulating one’s tone and feelings, namely expending emotional labor.

Responding to close ties. Participants noted that they also engaged in emotional labor while responding to close ties because they needed to regulate their feelings and ensure that they did not damage their existing relationships (e.g., “It’s okay if you need to step away for a bit and not wreck your family relationship. … it could be harder to untangle your family member’s issues because you’re so close to them.” [P27]). Though some participants said they avoided such potential confrontations altogether, others stated that they chose to address the situation. P14, for instance, tried to provide evidence to her father about misinformation: “So it’s tricky because … he doesn’t just trust me. Even though he is my father and my biggest advocate, it is hard to undo the power of misinformation … And I try to and I’ll get into arguments with him on it anyway.” Overall, participants noted that responding to close ties who believe in misinformation involves expending significant emotional labor to ensure that their relationships remain intact.

Design principles for support tools

To explore how this labor may be mitigated through support tools, we also showed participants a hypothetical response-support tool mock-up and asked them to provide feedback on it (see Appendix for a detailed mock-up description). This engendered some common design principles for software tools that may support people in identifying and responding to misinformation on social media.

Minimal effort. As noted above, people expend time and effort in collecting resources to identify misinformation and craft their responses. Since this work is especially repetitive and mentally exhausting, participants talked about alleviating the burden with a tool containing “specialized fact-checking resources that are easily accessible for the public or for specific spheres of work” [P12]. Some of these resources have been available through platform-led interventions like Facebook’s COVID-19 misinformation center and labels on posts containing misleading information. Thus, it is possible that these resources can help to reduce the time and effort users expend in identifying misinformation, with support tools mainly focusing on mitigating the emotional labor involved in responding to misinformation by helping people craft empathetic responses. However, a limitation of relying on platform-led interventions is that users do not always trust them (Saltz et al., 2021). Participants also mentioned that a tool that provided templates and blurbs to use while responding could help minimize the effort required to craft a response. For instance, P22 said, “you can have a quick example blurb response in italics to explain how you could do it.”

Autonomy. Though many found the idea of such ready-to-go artifacts useful, participants also stressed the need for maintaining autonomy while responding. They argued that composing a response was a subjective experience and a tool should only provide guiding opinions (e.g., “I’d be hesitant to use something that is trying to give someone else empathy … because I feel like it’d be disingenuous if I use like a copy pasted empathy sentence” [P19]). In general, participants said that they would like to make decisions independent of algorithms. On viewing the mock-ups, P23 noted that “since you are giving different avenues to correct the user or talk to the user it’s giving me more autonomy to make my own decisions, rather than relying on the AI or the computer.” Overall, participants indicated that tools to support them in identifying and responding to misinformation may have to be designed to strike a balance between minimizing effort through automation and preserving individual autonomy.

Tailored suggestions. One of the reasons for participants’ emphasis on autonomy was that the process of identifying and responding to misinformation is context dependent. An important contextual factor they mentioned was their relationship with the misinformation sharer. Given this issue, participants discussed the need for customized guidance from the tool, depending on who they were responding to. P15 said, “It might be a good initial question to say, ‘who is this person,’ ‘is it a good friend,’ ‘is it an acquaintance, a family member, a business associate, or just one of those thousands of connections you have on social media?’” As noted above, people’s relationship with whom they are responding to impacts their response. Thus, a tool that provides tailored suggestions may include an extensive repository of tips informed by research from areas like conflict management and interpersonal communication on the language one can use while responding to specific audiences such as older family members, younger family members, close friends, acquaintances, professional colleagues, and strangers online. Such a tool would allow users to select tips based on their situation and acquire guidance on how to frame their responses. This would help mitigate some of the emotional labor involved in the process, as users would have to expend less effort in framing responses that do not cause emotional and relational strife. At the same time, it would preserve individual autonomy by guiding users in the language they can use while framing a response rather than suggesting boilerplate responses they can copy and paste, regardless of their emotional and relational context.

Methods

To answer our research questions, which are detailed above, we ran two phases of semi-structured interviews with 29 participants via Zoom (15 in Phase 1, 16 in Phase 2, including two participants interviewed in both phases). We chose interviews as they help to capture “the experiences and lived meanings of the subjects’ everyday world” (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2018, p. 11), allowing us to understand the barriers people face in responding to misinformation on social media in their everyday lives (RQ1). We also used a response-support tool mockup as a probe during the Phase 2 interviews. Probes are suitable for recognizing user design needs (Blandford et al., 2016; Boehner et al., 2007), enabling us to examine people’s design needs for misinformation response support tools (RQ2). Moreover, as qualitative approaches engender new questions and considerations regarding technology design (Dourish, 2014), this approach also allowed us to reflect on ethical considerations associated with designing such support tools.

Recruitment & sampling

Phase 1 interviews were conducted between January and March of 2022, while Phase 2 interviews were conducted between April and June of 2022. For both phases, we engaged in purposive sampling, targeting a mix of misinformation research experts, online community moderators, people who respond to misinformation on social media as part of their work, and general social media users (see Appendix for demographic details). Here, we considered “work” in a broad sense: in some cases, responding was part of paid professional work, such as being a social media manager, journalist, or public health communicator, while in other cases, it arose due to unpaid work, such as being a community moderator or blogger. We wanted to include people who engage with misinformation to varying degrees and for different purposes to build in heterogeneity in the sample (Weiss, 1994). Participants were found through the researchers’ personal networks and by posting a call on social media. They were offered a $15 or $25 Amazon gift card as compensation, based on their level of expertise. In the findings, they are referred to by their Participant IDs to ensure anonymity.

Interview process & analysis

Interviews were conducted by experienced graduate students and undergraduate research assistants, all of whom are listed as authors. On average, Phase 1 interviews lasted for 30 minutes, while Phase 2 interviews were 38 minutes long. In Phase 1, participants were asked about their general use of social media, their engagement with misinformation on social media, and their process for identifying and responding to misinformation, including the barriers they face and the support they need (RQ1). In Phase 2, participants were asked about these topics and also shown a low-fidelity mock-up for a software tool described as a tool that supports people in responding to misinformation. The mock-up design was informed by insights gleaned during Phase 1 interviews and was used as a probe to help Phase 2 participants reflect on design principles associated with misinformation response-support tools (RQ2). The Appendix includes interview protocols, mock-up screenshots, and details about mock-up elements. Participants were asked to reflect on the utility of these elements and the design of their ideal response-support tool.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed using an online transcription service. Transcripts were analyzed using the thematic analysis technique (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The first and second author coded five transcripts independently and engaged in discussions to design a codebook. Disagreements between the authors were resolved through these discussions, and consensus was reached on the final codebook. Following this, the first and second author split the remaining transcripts and coded them independently, guided by the codebook.

Topics

Bibliography

Abend, L. (2022, March 6). Meet the Lithuanian ‘Elves’ fighting Russian disinformation. Time. https://time.com/6155060/lithuania-russia-fighting-disinformation-ukraine/

Blandford, A., Furniss, D., & Makri, S. (2016). Qualitative HCI research: Going behind the scenes. Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics, 9(1), 1–115. https://doi.org/10.2200/S00706ED1V01Y201602HCI034

Boehner, K. Vertesi, J., Sengers, P., & Dourish, P. (2007). How HCI interprets the probes. In CHI ’07: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1077–1086). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1240624.1240789

Bode, L., & Vraga, E. (2021). The Swiss cheese model for mitigating online misinformation. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 77(3), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2021.1912170

Bode, L., & Vraga, E. K. (2015). In related news, that was wrong: The correction of misinformation through related stories functionality in social media. Journal of Communication, 65(4), 619–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12166

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews. Sage. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781529716665

Coleman, K. (2021). Introducing birdwatch, a community-based approach to misinformation. X Blog. https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/product/2021/introducing-birdwatch-a-community-based-approach-to-misinformation

Dosono, B., & Semaan, B. (2019). Moderation practices as emotional labor in sustaining online communities: The case of AAPI identity work on Reddit. In CHI ’19: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–13). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300372

Dourish, P. (2014). Reading and interpreting ethnography. In J. S. Olsen & W. A. Kellog (Eds.), Ways of knowing in HCI (pp. 1–23). Springer.

Feng, K. K., Song, K., Li, K., Chakrabarti, O., & Chetty, M. (2022). Investigating how university students in the United States encounter and deal with misinformation in private WhatsApp chats during COVID-19. In Proceedings of the eighteenth symposium on usable privacy and security (SOUPS 2022) (pp. 427–446). Usenix. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/soups2022_full_proceedings.pdf

Geeng, C., Yee, S., & Roesner, F. (2020). Fake news on Facebook and Twitter: Investigating how people (don’t) investigate. In CHI ’20: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–14). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376784

Gillespie, T. (2022). Do not recommend? Reduction as a form of content moderation. Social Media + Society, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221117552

Grevet, C., Terveen, L. G., & Gilbert, E. (2014). Managing political differences in social media. In CSCW ’14:Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work & social computing (pp.1400–1408). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2531602.2531676

Guess, A. M., & Lyons, B. A. (2020). Misinformation, disinformation, and online propaganda. In N. Persily & J. A. Tucker (Eds.), Social media and democracy: The state of the field, Prospects for reform (pp. 10-33). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108890960

Hochschild, A. R. (2015). The managed heart. In A. Wharton (Ed.), Working in America (pp. 47–54). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315631011

Lee, J. H., Santero, N., Bhattacharya, A., May, E., & Spiro, E. S. (2022). Community-based strategies for combating misinformation: Learning from a popular culture fandom. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 3(5). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-105

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

Malhotra, P. (2020). A relationship-centered and culturally informed approach to studying misinformation on COVID-19. Social Media + Society, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120948224

Malhotra, P., & Pearce, K. (2022). Facing falsehoods: Strategies for polite misinformation correction. International Journal of Communication, 16(22), 2303–2324. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/18361/3762

Margolin, D. B., Hannak, A., & Weber, I. (2018). Political fact-checking on Twitter: When do corrections have an effect? Political Communication, 35(2), 196–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1334018

Menking, A., & Erickson, I. (2015). The heart work of Wikipedia: Gendered, emotional labor in the world’s largest online encyclopedia. In CHI ’15: Proceedings of the 33rd annual ACM conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 207–210). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702514

Nix, N., Zakrzewski, C., & Menn, J. (2023, September 23). Misinformation research is buckling under GOP legal attacks. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/09/23/online-misinformation-jim-jordan/

Reuters (2021, August 18). Facebook removes dozens of vaccine misinformation ‘superspreaders’. https://www.reuters.com/technology/facebook-removes-dozens-vaccine-misinformation-superspreaders-2021-08-18/

Roth, Y., & Pickels, N. (2020, May 11). Updating our approach to misleading information. X Blog. https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/product/2020/updating-our-approach-to-misleading-information

Rossini, P., Stromer-Galley, J., Baptista, E. A., & Veiga de Oliveira, V. (2021). Dysfunctional information sharing on WhatsApp and Facebook: The role of political talk, cross-cutting exposure and social corrections. New Media & Society, 23(8), 2430–2451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820928059

Saltz, E., Barari, S., Leibowicz, C., & Wardle, C. (2021). Misinformation interventions are common, divisive, and poorly understood. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(5). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-81

Savolainen, L. (2022). The shadow banning controversy: Perceived governance and algorithmic folklore. Media, Culture & Society, 44(6), 1091–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221077174

Silverman, H. (2019). Helping fact-checkers identify false claims faster. Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2019/12/helping-fact-checkers/

Tandoc Jr, E. C., Lim, D., & Ling, R. (2020). Diffusion of disinformation: How social media users respond to fake news and why. Journalism, 21(3), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919868325

Vogels, E. A., Perrin, A., & Anderson, M. (2020). Most Americans think social media sites censor political viewpoints. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/08/19/most-americans-think-social-media-sites-censor-political-viewpoints/

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Vraga, E. K., Tully, M., & Bode, L. (2020). Empowering users to respond to misinformation about Covid-19. Media and Communication, 8(2), 475–479. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i2.3200

Weiss, R. S. (1994). Learning from strangers: The art and method of qualitative interview studies. Simon and Schuster.

Wittenberg, C., Berinsky, A. J., Persily, N., & Tucker, J. A. (2020). Misinformation and its correction. In N. Persily & J. A. Tucker (Eds.), Social media and democracy: The state of the field, prospects for reform (pp. 163–198). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108890960

Wohn, D. Y. (2019). Volunteer moderators in Twitch micro communities: How they get involved, the roles they play, and the emotional labor they experience. In CHI 19: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–13). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300390

Funding

National Science Foundation, Award Number 49100421C0037; University of Washington Center for an Informed Public.

Competing Interests

None.

Ethics

Research deemed exempt by University of Washington IRB (ID: STUDY00014609). Participants provided informed verbal consent and determined gender categories.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

Participants granted consent based on the assumption that access to interview transcripts would be limited to the researchers, and this was also communicated in our IRB application. Thus, we are unable to share data outside of our research group.