Peer Reviewed

The impact of conspiracy belief on democratic culture: Evidence from Europe

Article Metrics

2

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

The spread of conspiracy theories is expected to have an increasing impact on the vitality of Western democracies and their political culture. Drawing on a 2022 survey from 10 European countries (with n = 20,449), this study uses narratives about immigration and COVID-19 to examine their relation to individual democratic attitudes and preferred forms of political participation. Overall, the findings suggest that while conspiracy belief can generally be seen as a side effect of democratic backsliding and an amplifier for the erosion of a vibrant civic culture, its interplay with people’s political attitudes varies and is dependent on the specific context. On the other hand, conspiracy believers generally tend to identify more strongly with the region and country in which they live.

Research Questions

- How widespread are political conspiracy narratives in Europe?

- How are attitudes towards democracy related with the tendency to believe in conspiracies?

- What is the relationship between conspiracy belief and people’s political efficacy, participatory behavior, and voting intention?

- How is the belief in political conspiracies associated with conventional forms of place-based political identification?

Essay Summary

- Using original survey data from 10 European countries conducted in the fall of 2022 (n = 20,449), I examined the prevalence of two different types of conspiracy beliefs and their implications for individual political preferences, attitudes towards democracy, and political participation.

- I found that low satisfaction with democracy, low trust in its institutions, and strong populist sentiments are associated with an increased likelihood of believing in political conspiracies.

- Believing in a political conspiracy also correlates with the perception that one’s own voice is not heard in politics. Yet this does not imply a more reserved assessment of one’s own political competence.

- Believing in a political conspiracy is related to a reduced willingness to participate in elections and a higher tendency of vote for far-right parties. In addition, those who believe in an immigration-related conspiracy are generally less likely to engage in other conventional forms of participation like signing a petition or participating in a demonstration.

- Believing in a political conspiracy is associated with a stronger tendency to identify with one’s own region and country.

- The study suggests that policymakers, political educators, and journalists should be more specific in their assessments of and approaches to individual groups, rather than lumping them all together under the label of “conspiracy theorists.”

Implications

In recent decades, belief in conspiracy theories has increased significantly in Western democracies. Polls show that, in many places today, a stable majority of the population sympathizes with at least one conspiracy narrative (Butter & Knight, 2020; Oliver & Wood, 2014; Walter & Drochon, 2022). In many cases, they take as their starting point events and developments that are described as “crises” in the public debate. The ultimate causes and circumstances of these crises are explained by alleging a sinister plot by a small group of powerful actors pursuing their secret agendas for their own benefit and against the common good (Douglas et al., 2019; Uscinski et al., 2016; van Prooijen & Douglas, 2017).

Against this backdrop, it is reasonable to assume that the spread of such conspiracy myths has a lasting impact on a country’s political culture,1Following Almond and Verba (1963), I use the term “political culture” here to refer to citizens’ values, beliefs, and attitudes toward their political system and the resulting participation behavior. its citizens’ engagement, and their attitudes toward democracy. This is strengthened by the fact that the recent proliferation of conspiracy theories appears to be closely linked to a rise in street protests, populist parties, and political violence. Right-wing extremist terrorists—such as those in Utøya, Norway in 2011; Christchurch, New Zealand in 2019; and El Paso, Texas in the United States in 2019—have referred to conspiracy myths in their confessions (Vanderwee & Droogan, 2023). Populist radical right (PRR) parties use the idea of an elitist conspiracy to mobilize their supporters (Bergmann, 2018; Pirro & Taggart, 2023). Accordingly, a large number of studies from various disciplines have addressed the recent spread of conspiracy narratives in Western democracies (Bordeleau, 2023; Douglas & Sutton, 2023), and many have investigated the individual correlates and psychological roots of believing in such plots (see Stasielowicz, 2022).

When it comes to examining the political implications of conspiracy belief, however, the literature is much more limited. In particular, apart from a few exceptions (Miller et al., 2016; Sutton & Douglas, 2020), little attention has been paid to the impact of conspiracy belief on individual preferences and civic attitudes. Moreover, while much of the existing literature focuses primarily on the United States, empirical studies that draw broader conclusions beyond the specific context of particular countries are rare (exceptions are Drochon, 2019; Walter & Drochon, 2022). This is especially true for Europe. Due to the paucity of cross-national data on conspiracy belief, many questions about its impact on political culture remain unanswered.

This paper addresses this gap. Using original survey data from 10 European countries collected in 2022 (n = 20,449), I examined the relationship between the propensity to believe in conspiracy myths and individual political attitudes. I adopted a comparative perspective that revealed differences between individual conspiracy theories by taking two narratives about immigration and COVID-19 as examples. The first referred to the “great replacement” myth which interprets mass immigration as part of a secret plan by sinister elites to destroy Western culture by replacing the original population with people of non-European origin (Camus, 2011; Ekman, 2022; Feola, 2021). Accordingly, the item I used in my study reads: “There is a group of people in this country who are trying to replace native-born population with immigrants.” The second narrative I addressed in my study took up the issues of economic profit and power interests (“Big Pharma”) as well as vaccination skepticism (“anti-vax”) and combined them into a conspiracy claim that is set in the context of the coronavirus pandemic. In doing so, the item not only addressed an influential variant but also established an interpretive link to the whole field of COVID-related conspiracy myths and is considered to be a good indicator of the general tendency to believe in these types of narratives (Pertwee et al., 2022; Pummerer et al., 2022; van Mulukom et al., 2022). The item reads: “Out of consideration for the pharmaceutical lobby, the government is concealing the potential side effects and long-term damage caused by the COVID-19 vaccines.”

Through this approach, the study contributes in several ways to a better understanding of the impact of conspiracy theories on European democracies and their political culture. First, it provides a more nuanced picture of how widespread these theories are in Europe. By taking two narratives about immigration and the COVID-19 pandemic as examples, I show that the belief in conspiracies meets different levels of acceptance in different countries and different social groups.

Second, I found that in all studied European countries, indicators of democratic backsliding, such as low satisfaction with democracy, little trust in its institutions, and strong populist sentiments are associated with an increased openness to conspiracy narratives. This complements and confirms existing research, particularly on the United States, which suggests a strong relationship between conspiracy belief and democratic disaffection (Eberl et al., 2021; Enders et al., 2023; Guinjoan & Galais, 2023; Imhoff & Bruder, 2014; Thielmann & Hilbig, 2023).

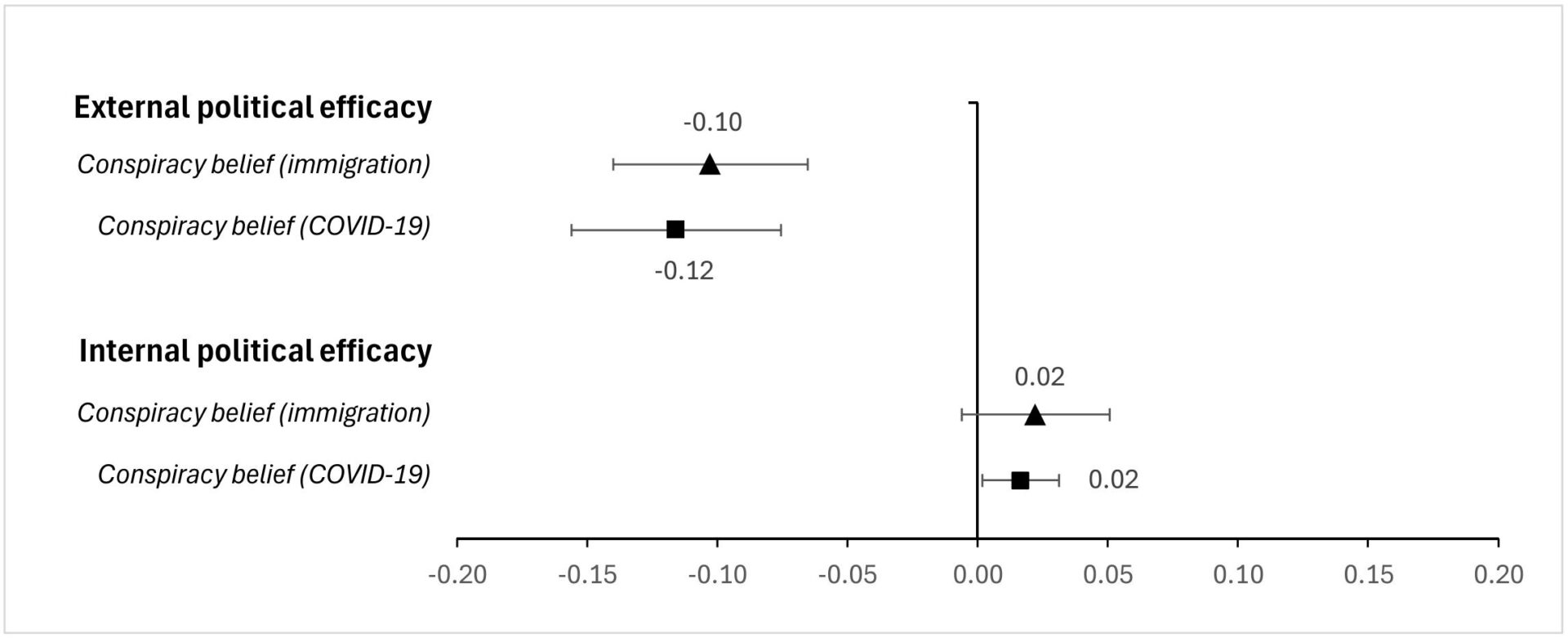

Third, I present evidence that people who subscribe to conspiracy theories are more likely to believe that their voices are not heard and that they have no real influence, confirming that belief in conspiracy narratives runs counter to the idea of an empowered and engaged citizenry associated with a vibrant democracy by increasing perceptions of individual political powerlessness and low political efficacy (Jolley & Douglas, 2013; Rullo & Telesca, 2023). On the other hand, however, I found no significant correlation with people’s assessment of their own competence to participate in politics. This contradicts studies suggesting that conspiracy belief also has a negative effect on internal political efficacy (Ardèvol-Abreu et al., 2020). It also contradicts the reverse argument, according to which conspiracy theories may increase individuals’ self-evaluation of their competence by promoting the feeling that they are better able than anyone else to understand political issues and participate in political processes with the help of their secret insights (Lantian et al., 2017; Rullo & Telesca, 2023).

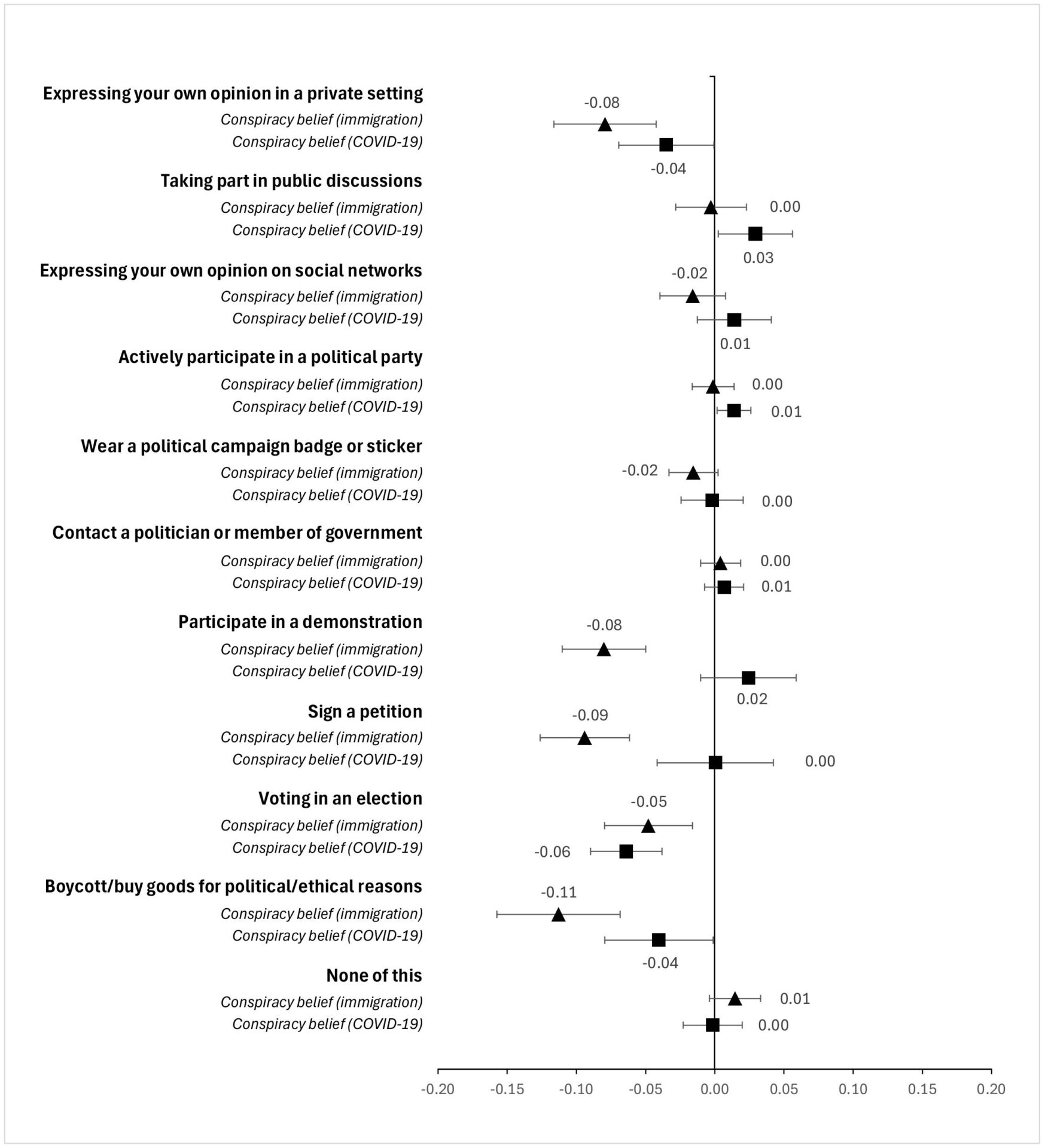

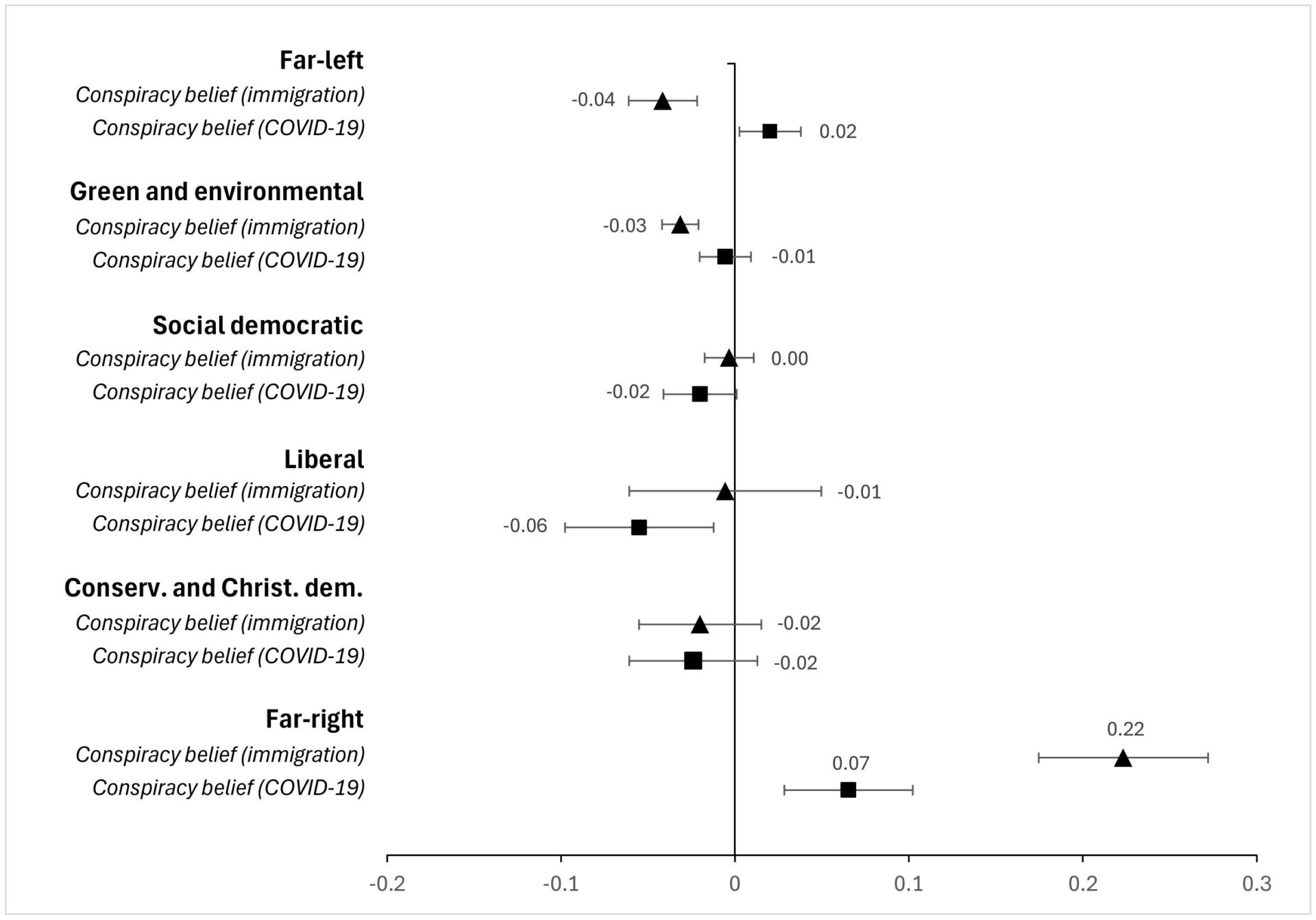

Fourth, with regard to the concrete practice of political engagement, my analysis revealed that, on average, believing in conspiracies is associated with a below-average willingness to participate in politics. Those who believe that political events and developments are secretly controlled by small circles of powerful and corrupt elites seem to have little desire to get involved in solving these problems (Ardèvol-Abreu et al., 2020; Enders, 2019). Particularly supporters of the immigration-related great replacement myth show low levels of trust in the effectiveness of democratic processes and are more reluctant to participate than those who believe in a COVID-19 conspiracy. However, I also found that the supporters of conspiracy narratives generally show an increased likelihood of voting for far-right parties. This is not surprising, as, traditionally, ideological orientation, including partisan and ideological self-identification, as well as affinity towards political extremism, appeared to be a significant factor in determining susceptibility to ideologically motivated conspiracy endorsements (Appelrouth, 2017; Enders et al., 2020; Hofstadter, 1965; Miller et al., 2016; Walter & Drochon, 2022).

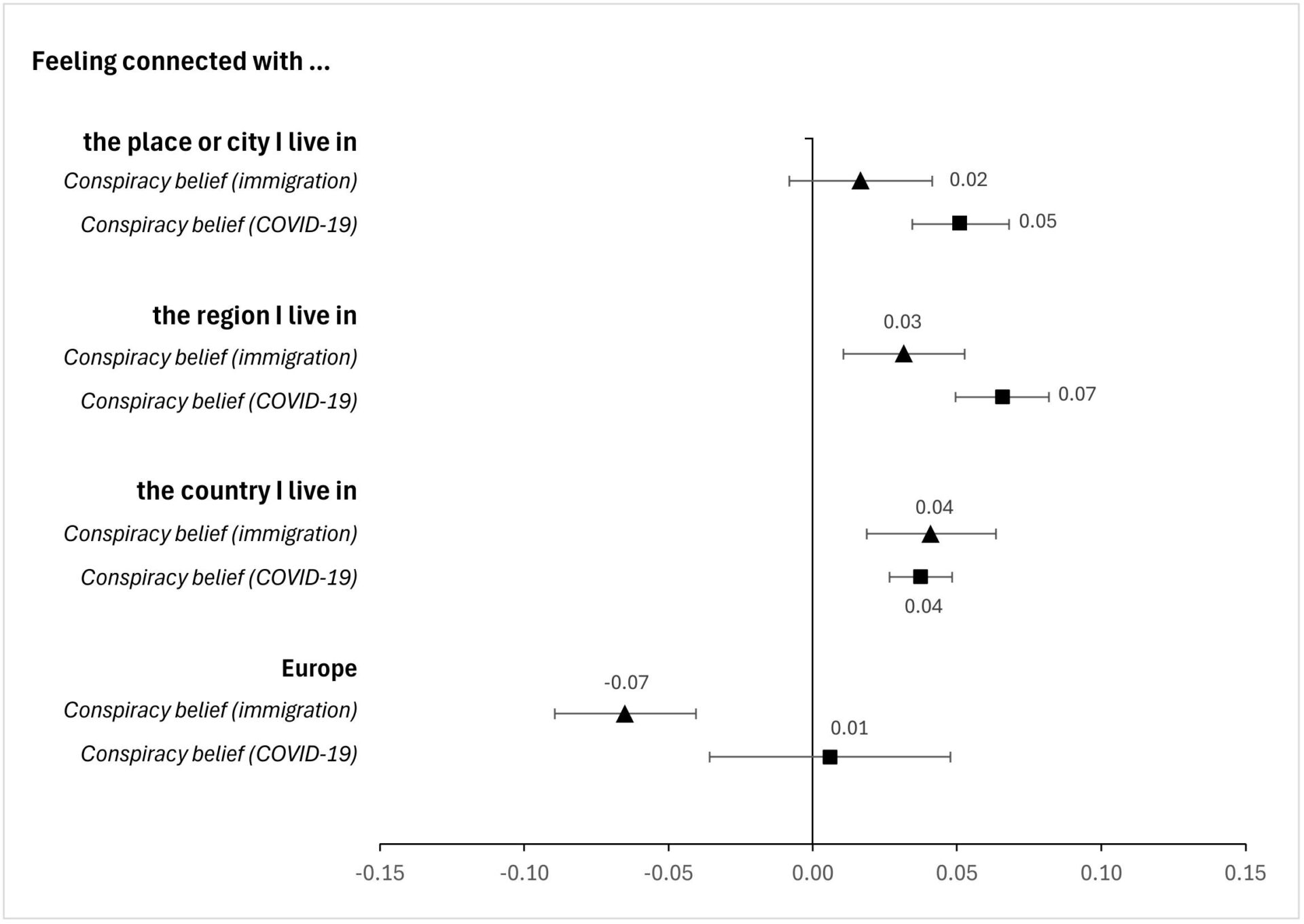

Finally, my analysis revealed that those who believe in political conspiracies are, on average, more inclined to place-based forms of identification with the region and country in which they live, and may therefore be more susceptible to local and national patriotic narratives (Fitzgerald, 2018; Hegewald, 2024). This supports the idea that one of the underlying factors contributing to the acceptance of conspiracy theories is the desire for social belonging, as affiliation with a socially respected group provides an opportunity to increase one’s own self-esteem (Douglas et al., 2017).

These findings suggest that the impact of the recent spread of conspiracy theories on individual political attitudes is not fully generalizable. While belief in political conspiracies generally correlates with indicators of democratic disaffection, most adherents of a COVID-19 conspiracy narrative, unlike those of the great replacement myth, do not consider a democratic form of government less important than others and do not differ much from the average population in their participatory behavior. Moreover, large parts of those who find conspiracy theories plausible in the context of the COVID-19 vaccination are hardly conspicuous in their political participation behavior, nor are they supporters of right-wing extremist parties.

Policymakers, political educators, and journalists should therefore be more specific in their assessments of and approaches to individual groups, rather than lumping them all together under the label of “conspiracy theorists.” Countermeasures, on the other hand, should address specific narratives and issues, rather than the general psychological background of conspiracy thinking. They should focus on the needs and living conditions of those social groups (such as low-income earners and people with low levels of education) in which the particular conspiracy narrative is most prevalent. They should concentrate their efforts on the media that are most commonly used by the respective age group. Finally, they should include in their strategies those stakeholders—associations, clubs, and churches—that are most relevant for organizing solidarity and local cohesion in a given socio-spatial context (such as rural and peripheral areas).

Similar conclusions could be drawn with respect to individuals and organizations, such as political parties, that intend to spread misinformation and to manipulate public opinion. Here, my findings suggest that in the European democracies I studied, certain political attitudes provide a common ground for political conspiracy belief: For example, individual experiences of disenchantment and distrust with politics, feelings of lack of self-efficacy, and an associated stronger attachment to traditional forms of collective identification. Those who spread misinformation and conspiracy narratives ultimately seek to profit from these feelings by offering the prospect of exclusive insights and advances in knowledge, which in turn promise to be a new source of social status, respect, or even political influence. In light of my findings, I would conclude that different segments of society are more or less receptive to such efforts, depending on the context, the issue, and people’s affective investment in the political problems involved.

Findings

Finding 1: Belief in political conspiracies is not evenly spread across Europe. There are significant differences both between countries and between social groups.

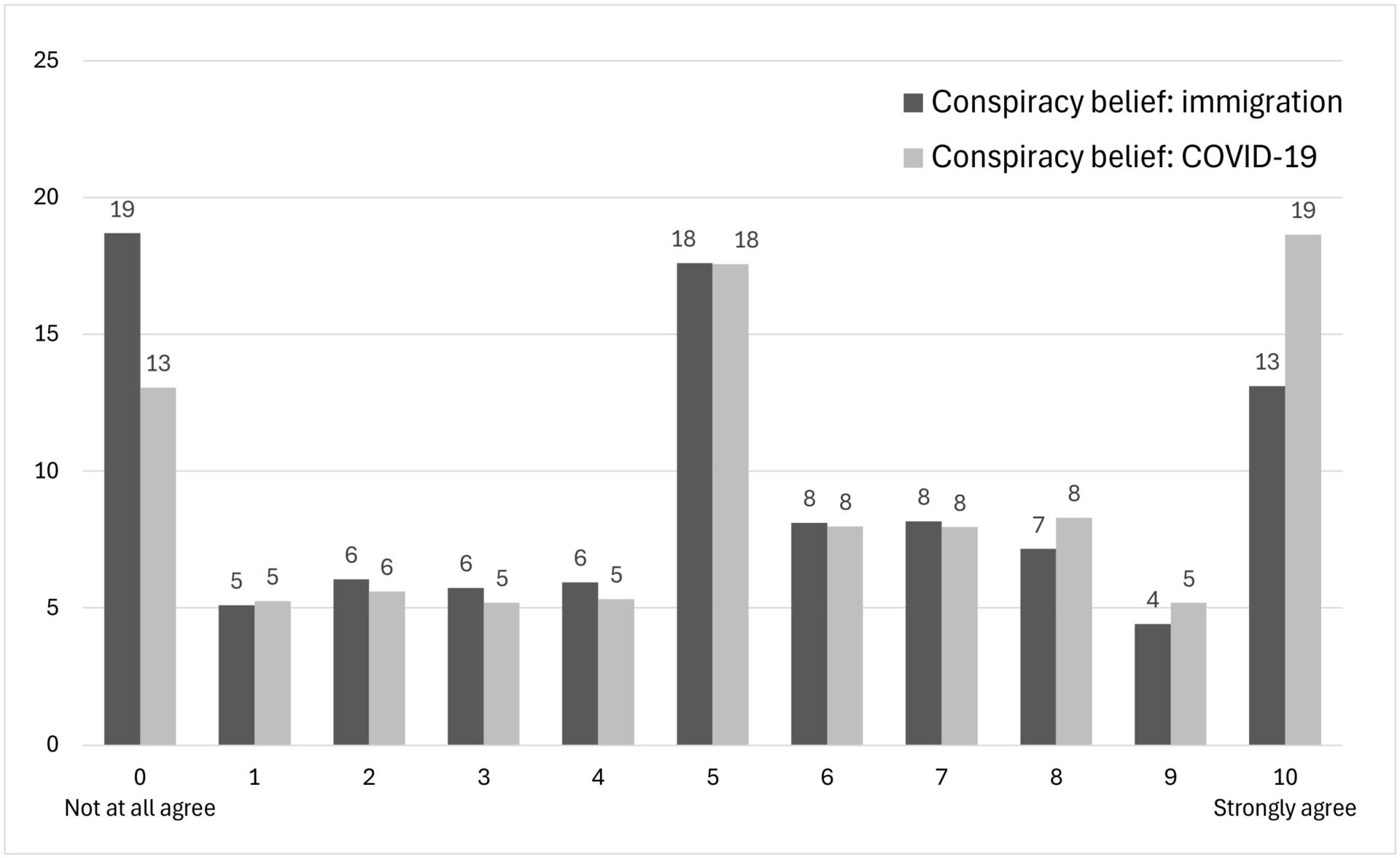

Support for conspiracy theories is not confined to small splinter groups within society. In fact, 31.7% of respondents strongly agreed with at least one of the two statements used to measure conspiracy belief, choosing responses between 9 and 10 on a scale from 0 (do not agree at all) to 10 (completely agree). 9.7% strongly agreed with both statements.

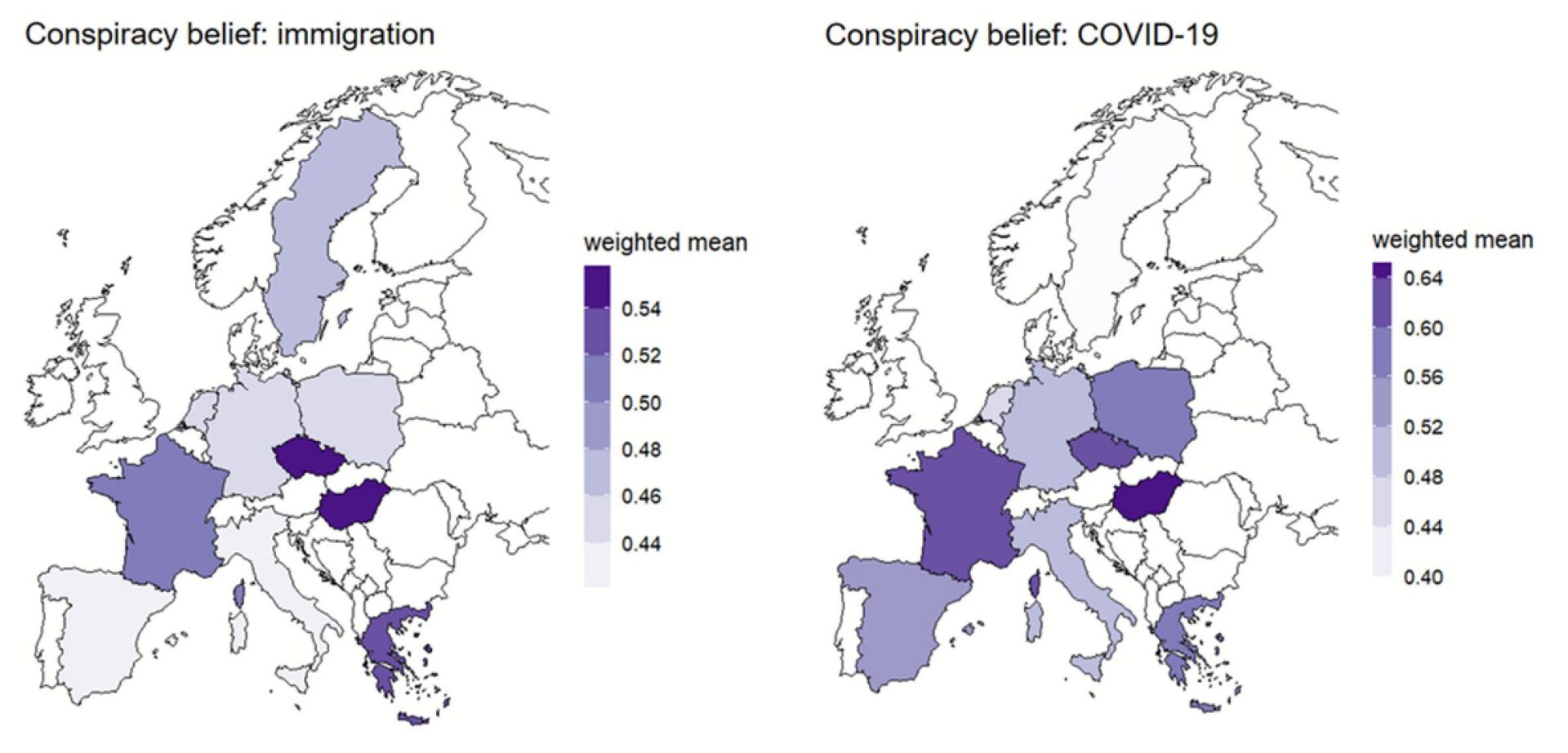

Moreover, a total of 61.7% of Europeans are generally open to at least one of the two conspiracy narratives by choosing responses between 6 and 10 on an 11-point scale. 27.3% tend to agree with both statements. Further descriptive analyses revealed clear differences between countries. Conspiracy belief about immigration is particularly widespread in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Greece, and France (Figure 1). The same countries, as well as Poland, also have above-average proportions of people who believe that a small group of powerful actors are engaged in sinister machinations in connection with COVID-19 vaccinations. In contrast, the lowest levels of support for these conspiracy theories are found in Spain and Italy for immigration and in Sweden and the Netherlands for COVID-19.

Explanations for these differences between countries are rare, so only some speculative considerations can be made here. For example, the data suggest that conspiracy thinking is generally more prevalent in former Eastern bloc countries. Poland’s lower susceptibility to the great replacement myth may be related to the mass influx of refugees from Ukraine in recent years. Political attitudes in Greece, in contrast, may be influenced by the country’s special role as a major arrival and transit country for refugees. Finally, France is the home of Renaud Camus, whose influential book— first in France and then across Europe—has contributed significantly to the recent spread of the thesis of “le grand replacement” (Camus, 2011).

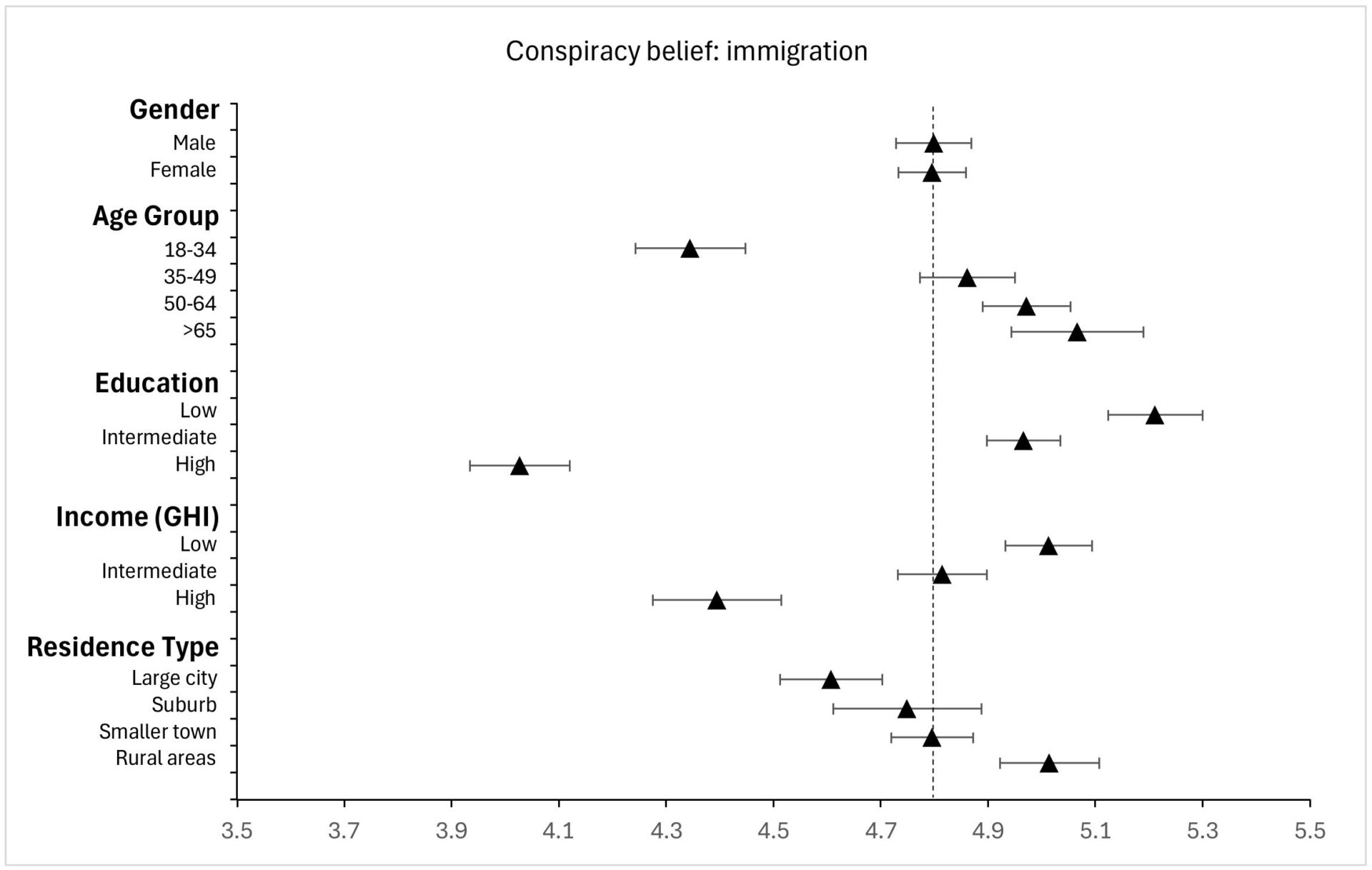

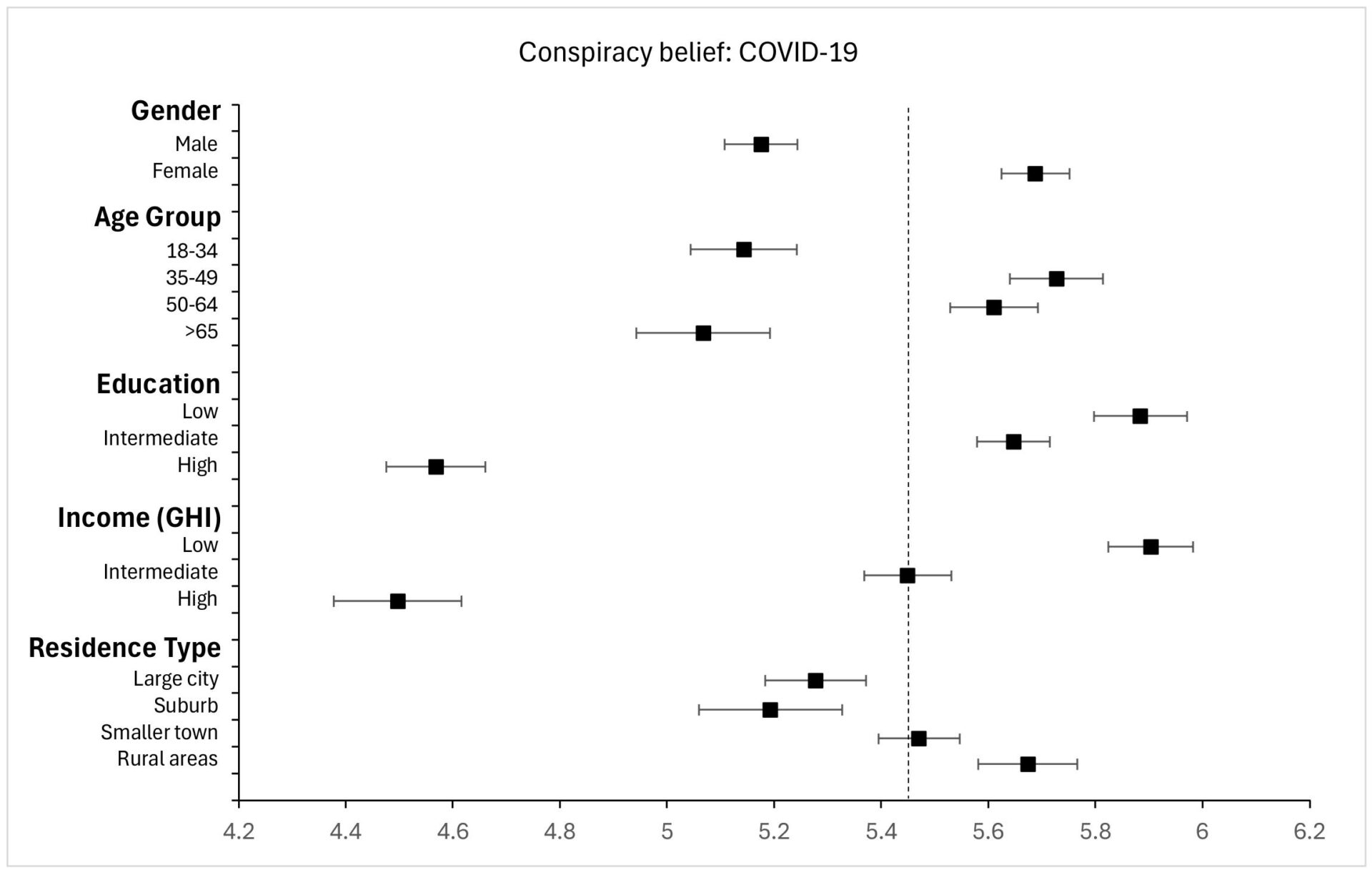

The attractiveness of conspiracy narratives also varies among different social subgroups (Figure 2). Young people, for example, are on average less likely to believe in conspiracies than middle-aged adults. People over the age of 65 are significantly more inclined to see secret machinations at work when it comes to immigration. This is consistent with prior research (Walter & Drochon, 2022). At the same time, people aged 65+ are the least susceptible group to conspiracies about the COVID-19 pandemic. This may be related to the fact that these individuals face significantly higher health risks and may therefore be more likely to follow the advice of medical professionals about the pandemic and possible vaccinations than others (De Coninck et al., 2021; Uscinski et al., 2020).

Further correlations can be found between the belief in conspiracies and education, income, and people’s place of residence. The deeper roots of these frequently observed correlations have also been debated in the literature (Douglas et al., 2019; Freeman & Bentall, 2017; van Mulukom et al., 2022). Possible explanations suggest that education, in particular, conveys a greater sense of social control and provides people with a set of cognitive attributes and competencies that enable them to resist conspiracy claims (Craft et al., 2017; Douglas et al., 2016; van Prooijen, 2017).

Finally, according to my data, women on average showed a significantly higher propensity to agree with the COVID-19-related conspiracy item than men, while there is no such gender difference when it comes to immigration. This result has also been found in several other studies (van Mulukom et al., 2022). These findings also complement the results of psychological studies that have found that in the context of the pandemic and related countermeasures such as lockdowns, women are at a higher risk of developing depression and are also more prone to conspiracy beliefs than men (Patsali et al., 2020).

Finding 2: Low satisfaction with one’s own country’s democracy, low trust in its institutions, and strong populist sentiments are associated with an increased likelihood of believing in conspiracy narratives. A general preference for democracy as an idea and as a form of government does not necessarily influence this susceptibility.

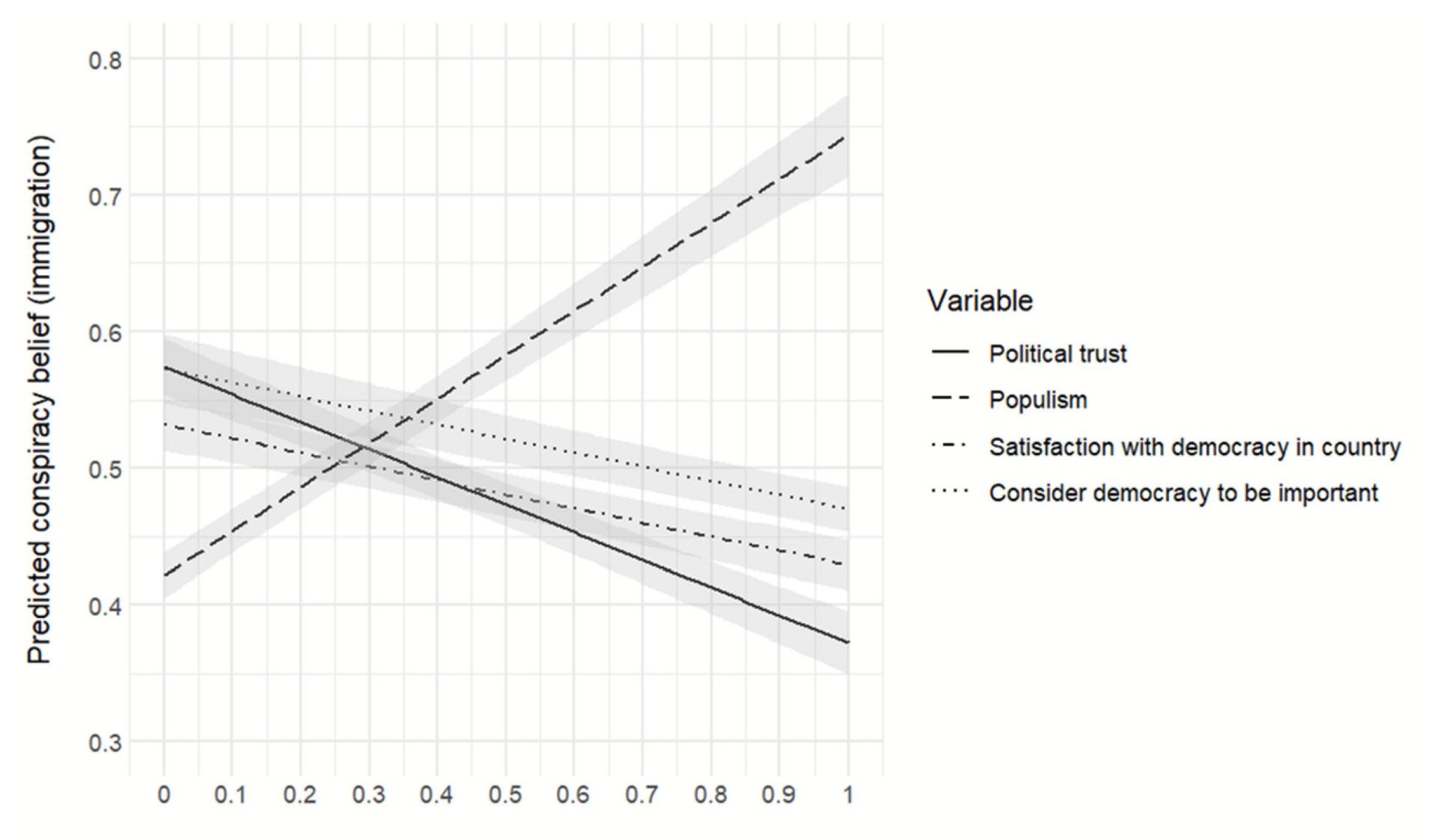

Are negative attitudes towards democracy associated with a higher tendency to believe in conspiracies? To answer this question, I employed robust linear probability models in which higher values of the dependent variable indicate a stronger attachment to conspiracy statements. I added independent variables that represent indicators of democratic trust or disaffection to assess whether they condition the propensity of conspiracy belief. For this, I used established measures of the perceived importance of democracy, satisfaction with democracy in one’s own country, an index measuring trust in political institutions, and an index of populist attitudes (see Table A1). I expected that people with low trust in democracy, its institutions, and its elites are more susceptible to this type of ideology. This was confirmed for both issues, as the estimates in my regression models show a significant negative and, in the case of an index measuring populist attitudes, a strong positive relationship between attitudes toward democracy and conspiracy thought. This correlation holds even when I include other variables in the model that are likely to affect a person’s propensity to believe in political conspiracy theories (including country-fixed effects).

Figure 3 displays the resulting graphs that fit the respective relationships based on the predicted values for immigration-related and COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs. The findings align with my expectations, suggesting that for each of the two issues, higher satisfaction with democracy, greater trust in democratic institutions, lower populism, and stronger views that living in a democratic country is important are related to a lower propensity to believe in conspiracy myths. However, which side influences the other (i.e., what is cause and what is effect) remains undetermined here. It could be that attitudes toward democracy worsen after people begin to believe in conspiracies. Conversely, an increased tendency to believe in conspiracies could also be a direct result of declining trust in the democratic system, its institutions, and its elites.

The only exception to this is conspiracy belief related to the coronavirus pandemic. Here, the view that democracy is important turns out to have no significant effect (see Figure C2 in Appendix C). This suggests that those who believe that pandemic policy was influenced by secret plots still support democracy as a general idea and as a form of government, even if they are dissatisfied with the current form it takes in their country.

Finding 3: People who believe in conspiracy narratives have, on average, lower external political efficacy. They are more likely to believe that their voices are not heard in politics and that they have no real political influence. However, they do not feel less informed about politics or less able to actively participate in political debates.

Examining the relationship between conspiracy thinking and perceptions of political self-efficacy and empowerment, i.e. the extent to which people feel that their individual actions actually influence the political process, I distinguished between external and internal political efficacy. While the former refers to the feeling that the government will respond to one’s demands, the latter relates to people’s self-perception of their ability to understand politics and to participate in political processes (Lane, 1959). I used both measures as dependent variables in robust linear regression models (see Figure 4). They demonstrate that both forms of conspiracy belief are negatively correlated with external political efficacy. The more strongly people in the studied European countries lean towards one of the two conspiracy theories, the less they believe that their voice is heard in politics and that they have a say in what the government does. However, the same relationship cannot be observed for internal political efficacy. People who agree with a conspiracy about immigration feel equally capable, and people who believe in a conspiracy about the COVID-19 vaccination feel slightly more capable than average of actively participating in a conversation about political issues (see Figure 6).

Finding 4: Believing in conspiracies is associated with a reduced overall willingness to participate in politics and an increased likelihood of voting for far-right parties. This finding is stronger for the immigration-related conspiracy narrative, while the belief in the COVID-19-related conspiracy shows less consistent correlations.

Overall, the relationship between conspiracy belief and people’s preferred forms of political participation is rather weak, in many cases even insignificant (see Figure 5). Nevertheless, some tendencies can be identified. The supporters of both conspiracy narratives appear to be more reluctant to express their political opinions in a private setting. Both groups are also less willing to change their consumer behavior for political or moral reasons and are less likely to vote in an election. Among those who believe in an immigration conspiracy, the willingness to attend a demonstration and to sign a petition is also below average, which is not the case for those who believe in a conspiracy regarding the COVID-19 vaccination (see Figure 5).

Focusing more closely on political participation through voting, I also estimated the extent to which conspiracy belief can be considered as a predictor of voting for a particular party family. For this analysis, I employed the categorization of parties commonly used in the literature (Langsæther, 2023; see Table A2 in Appendix A for the allocation of parties to party families in the various countries). Using estimations based on robust logistic regression models, where the dependent variable indicates whether the respondent intends to vote for a particular party or not, I found a significant correlation of moderate strength only in the case of far-right parties (see Figure 6).

This finding confirms the results of Walter and Drochon (2022), who also suggested that conspiracy belief is particularly prevalent among supporters of the far-right. However, my analysis reveals that this relationship between conspiracy belief and far-right voting is also dependent on the particular content of the conspiracy theory. In the case of a COVID-19-related narrative, for example, the results are much less clear than in the case of the immigration-related great replacement myth.

Finding 5: Believing in conspiracies is associated with a stronger tendency toward place-based forms of identification related to one’s own hometown, region, or country, but not related to Europe.

Consistent with the literature, I assumed that the belief in conspiracies is related to the desire for social affiliation and is therefore associated with place-based patterns of ingroup and outgroup formation (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Using robust linear modeling, I confirmed this assumption. As Figure 7 shows, people in the 10 studied European countries who agree with a conspiracy narrative are slightly more inclined to place-based forms of identification. However, this applies only to identification with the city, region, and country in which they live, not to a (supranational) identification with Europe.

Methods

To address my main research question about the interplay between the recent spread of conspiracy theories and Europe’s democratic political cultures, I examined how believing in a conspiracy is related to individual attitudes towards democracy, political efficacy, participatory behavior, voting intentions, and place-based forms of political identification. My analysis was based on a survey conducted in partnership with YouGov in 10 European Union countries (Herold et al., 2023). A total of 20,449 people aged 18 and over were interviewed in the fall of 2022. Data was collected in the Czech Republic (n = 2,101), France (n = 2,117), Germany (n = 2,091), Greece (n = 1,587), Hungary (n = 2,069), Italy (n = 2,123), the Netherlands (n = 2,095), Poland (n = 2,055), Spain (n = 2,105) and Sweden (n = 2,106). The countries were selected with the aim of obtaining a total group of respondents that reflects the socio-spatial and political-cultural diversity of the European Union, while at the same time representing a significant majority (around 80%) of its population. Sampling was based on (regional) online access panels. To reflect the distribution of population characteristics in each country, quotas were set based on age, gender, region, and education level. A subsequent weighting process was used to adjust for additional distributional differences between the sample and the populations in each country.

To measure conspiracy belief, I used responses to two questions asking people to place themselves on an 11-point social ladder. The questions focused on issues that have been at the center of controversial public discussions in recent years, and have also been the subject of election campaigns, protests and political initiatives across Europe: immigration and the COVID-19 pandemic. The items read as follows: 1) on the issue of immigration: “There is a group of people in this country who are trying to replace native-born population with immigrants” and 2) on COVID-19: “Out of consideration for the pharmaceutical lobby, the government conceals potential side effects and long-term damage caused by the COVID-19 vaccines.” Figure 8 shows the distribution of these two items across all 10 countries.

I employed robust linear and logistic regression analyses that incorporated multiple explanatory measures. The wording and coding of these measures are listed in Tables A1 and B1 in Appendices A and B. They include:

- satisfaction with democracy (in general and with respect to the specific democratic system in people’s home country)

- political trust (an index calculated from seven survey items)

- populism (an index calculated from nine survey items according to Castanho Silva et al., 2019)

- internal and external political efficacy

- political participation (according to ten different forms)

- voting intentions (determined according to the parties of each country and then assigned to party families)

- and place-based identification (according to the city, region, and country where respondents live, as well as Europe)

Within the limits of the dataset, I also included a set of individual-level control variables, such as gender, age (in years), education (with the levels low, medium, and high), income2To make it comparable across all countries, I used a factor variable indicating whether its value belongs to the upper (“high income”), the middle (“middle income”), or the lower level of a country’s income structure. Similar categories are used for education where “high” refers to high secondary or academic degrees (see Table A1). and other measures that I assumed to influence an individual’s tendency to believe in conspiracies including political interest and left-right self-positioning. To adjust for any time-invariant differences across countries that might explain possible regional affinities to certain forms of conspiracy belief, I added country-fixed effects and calculated robust standard errors clustered by country.

Topics

Bibliography

Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton University Press.

Appelrouth, S. (2017). The paranoid style revisited: Pseudo-conservatism in the 21st century. Journal of Historical Sociology, 30(2), 342–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/johs.12095

Ardèvol-Abreu, A., Gil de Zúñiga, H., & Gámez, E. (2020). The influence of conspiracy beliefs on conventional and unconventional forms of political participation: The mediating role of political efficacy. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(2), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12366

Bergmann, E. (2018). Conspiracy & populism: The politics of misinformation. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90359-0

Bordeleau, J.-N. (2023). I trends: A review of conspiracy theory research: Definitions, trends, and directions for future research. International Political Science Abstracts, 73(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/00208345231157664

Butter, M., & Knight, P. (2020). General introduction. In M. Butter & P. Knight (Eds.), Routledge handbook of conspiracy theories (pp. 1–8). Routledge.

Camus, R. (2011). Le grand remplacement: Introduction au remplacisme global [The great replacement: Introduction to global remplacism]. Reinharc.

Castanho Silva, B., Andreadis, I., Anduiza, E., Blanuša, N., Morlet Corti, Y., Delfino, G., Rico, G., Ruth, S. P., Spruyt, B., Steenbergen, M., & Littvay, L. (2019). Public opinion surveys: A new scale. In K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay, & C. Rovira Kaltwasser (Eds.), Routledge studies in extremism and democracy. The ideational approach to populism: concept, theory, and analysis (pp. 150–177). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315196923

Craft, S., Ashley, S., & Maksl, A. (2017). News media literacy and conspiracy theory endorsement. Communication and the Public, 2(4), 388–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047317725539

De Coninck, D., Frissen, T., Matthijs, K., d’Haenens, L., Lits, G., Champagne-Poirier, O., Carignan, M.-E., David, M. D., Pignard-Cheynel, N., Salerno, S., & Généreux, M. (2021). Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: Comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 646394. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646394

Douglas, K. M., & Sutton, R. M. (2023). What are conspiracy theories? A definitional approach to their correlates, consequences, and communication. Annual Review of Psychology, 74, 271–298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031329

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., & Cichocka, A. (2017). The psychology of conspiracy theories. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 538–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417718261

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., Callan, M. J., Dawtry, R. J., & Harvey, A. J. (2016). Someone is pulling the strings: Hypersensitive agency detection and belief in conspiracy theories. Thinking & Reasoning, 22(1), 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2015.1051586

Douglas, K. M., Uscinski, J. E., Sutton, R. M., Cichocka, A., Nefes, T., Ang, C. S., & Deravi, F. (2019). Understanding conspiracy theories. Political Psychology, 40(S1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12568

Drochon, H. (2019). Who believes in conspiracy theories in Great Britain and Europe? In J. E. Uscinski (Ed.), Conspiracy theories and the people who believe them (pp. 337–346). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190844073.001.0001

Eberl, J.-M., Huber, R. A., & Greussing, E. (2021). From populism to the “plandemic”: why populists believe in COVID-19 conspiracies. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31(1), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924730

Ekman, M. (2022). The great replacement: Strategic mainstreaming of far-right conspiracy claims. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 28(4), 1127–1143. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565221091983

Enders, A., Klofstad, C., Stoler, J., & Uscinski, J. E. (2023). How anti-social personality traits and anti-establishment views promote beliefs in election fraud, QAnon, and COVID-19 conspiracy theories and misinformation. American Politics Research, 51(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X221139434

Enders, A. M. (2019). Conspiratorial thinking and political constraint. Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(3), 510–533. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz032

Enders, A. M., Smallpage, S. M., & Lupton, R. N. (2020). Are all ‘birthers’ conspiracy theorists? On the relationship between conspiratorial thinking and political orientations. British Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 849–866. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000837

Feola, M. (2021). “You will not replace us”: The melancholic nationalism of whiteness. Political Theory, 49(4), 528–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591720972745

Fitzgerald, J. (2018). Close to home: Local ties and voting radical right in Europe. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108377218

Freeman, D., & Bentall, R. P. (2017). The concomitants of conspiracy concerns. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(5), 595–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1354-4

Guinjoan, M., & Galais, C. (2023). I want to believe: The relationship between conspiratorial beliefs and populist attitudes in Spain. Electoral Studies, 81, 102574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102574

Hegewald, S. (2024). Locality as a safe haven: Place-based resentment and political trust in local and national institutions. Journal of European Public Policy, 31(6), 1749–1774. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2291132

Herold, M., Joachim, J., Otteni, C., & Vorländer, H. (2023). Polarization in Europe: An Analysis of Ten European Countries. Mercator Forum Migration and Democracy. https://forum-midem.de/2023/08/24/polarization-in-europe-a-comparative-analysis-of-ten-european-countries

Hofstadter, R. (1965). The paranoid style in American politics and other essays. Knopf.

Imhoff, R., & Bruder, M. (2014). Speaking (un-)truth to power: Conspiracy mentality as a generalised political attitude. European Journal of Personality, 28(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1930

Jolley, D., & Douglas, K. M. (2013). The social consequences of conspiracism: Exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon footprint. British Journal of Psychology, 105(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12018

Lane, R. E. (1959). Political life: Why people get involved in politics. The Free Press.

Langsæther, P. E. (2023). Party families in Western Europe. Routledge studies on political parties and party systems. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429442728

Lantian, A., Muller, D., Nurra, C., & Douglas, K. M. (2017). “I know things they don’t know!”: The role of need for uniqueness in belief in conspiracy theories. Social Psychology, 48(3), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000306

Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L., & Farhart, C. E. (2016). Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning: The moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 824–844. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12234

Oliver, J. E., & Wood, T. J. (2014). Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 952–966. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12084

Patsali, M. E., Mousa, D.-P. V., Papadopoulou, E. V. K., Papadopoulou, K. K. K., Kaparounaki, C. K., Diakogiannis, I., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2020). University students’ changes in mental health status and determinants of behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113298

Pertwee, E., Simas, C., & Larson, H. J. (2022). An epidemic of uncertainty: Rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nature Medicine, 28(3), 456–459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01728-z

Pirro, A. L. P., & Taggart, P. (2023). Populists in power and conspiracy theories. Party Politics, 29(3), 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688221077071

Pummerer, L., Böhm, R., Lilleholt, L., Winter, K., Zettler, I., & Sassenberg, K. (2022). Conspiracy theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211000217

Rullo, M., & Telesca, G. (2023). Consequences of conspiracy theories on political efficacy and political participation. In L. Fabbri & C. Melacarne (Eds.), Understanding radicalization in everyday life (pp. 260–276). McGraw-Hill.

Stasielowicz, L. (2022). Who believes in conspiracy theories? A meta-analysis on personality correlates. Journal of Research in Personality, 98, 104229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2022.104229

Sutton, R. M., & Douglas, K. M. (2020). Conspiracy theories and the conspiracy mindset: Implications for political ideology. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.02.015

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 56–65). Brooks/Cole.

Thielmann, I., & Hilbig, B. E. (2023). Generalized dispositional distrust as the common core of populism and conspiracy mentality. Political Psychology, 44(4), 789–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12886

Uscinski, J. E., Klofstad, C., & Atkinson, M. D. (2016). What drives conspiratorial beliefs? The role of informational cues and predispositions. Political Research Quarterly, 69(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912915621621

Uscinski, J. E., Enders, A. M., Klofstad, C., Seelig, M., Funchion, J., Everett, C., Wuchty, S., Premaratne, K., & Murthi, M. (2020). Why do people believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories? Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-015

van Mulukom, V., Pummerer, L. J., Alper, S., Bai, H., Čavojová, V., Farias, J., Kay, C. S., Lazarevic, L. B., Lobato, E. J. C., Marinthe, G., Pavela Banai, I., Šrol, J., & Žeželj, I. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 301, 114912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114912

van Prooijen, J.-W. (2017). Why education predicts decreased belief in conspiracy theories. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 31(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3301

van Prooijen, J.-W., & Douglas, K. M. (2017). Conspiracy theories as part of history: The role of societal crisis situations. Memory Studies, 10(3), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698017701615

Vanderwee, J., & Droogan, J. (2023). Testing the link between conspiracy theories and violent extremism: A linguistic coding approach to far-right shooter manifestos. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2023.2258952

Walter, A. S., & Drochon, H. (2022). Conspiracy thinking in Europe and America: A comparative study. Political Studies, 70(2), 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720972616

Funding

This study was supported by Mercator Forum Migration and Democracy (MIDEM), a research center at TUD Dresden University of Technology funded by Stiftung Mercator.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethics

The study is based on a survey conducted through regional online access panels. Participation in the survey was voluntary and participants could opt out at any time. Gender information about participants was collected using standard questions.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BJOCX5