Peer Reviewed

Examining accuracy-prompt efficacy in combination with using colored borders to differentiate news and social content online

Article Metrics

7

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Recent evidence suggests that prompting users to consider the accuracy of online posts increases the quality of news they share on social media. Here we examine how accuracy prompts affect user behavior in a more realistic context, and whether their effect can be enhanced by using colored borders to differentiate news from social content. Our results show that accuracy prompts increase news-sharing quality without affecting sharing of social (non-news) posts or “liking” behavior. We also find that adding colored borders around news posts increased overall engagement with news regardless of veracity, and decreased engagement with social posts.

Research Questions

- How do accuracy prompts affect different types of social media posts (news, social) and different forms of engagement (sharing, liking) in a simulated newsfeed setting?

- What is the effect of using colored borders to distinguish news from social posts on social media?

- Does adding colored borders around news posts increase the impact of accuracy prompts?

Essay Summary

- We conducted a large online survey experiment in which 1,524 American social media users were randomly assigned to receive either an accuracy prompt, an accuracy prompt plus purple-colored borders around news posts, or a control condition with no intervention. Participants were then given a simulated social media newsfeed containing a mix of true news posts, false news posts, and social (non-news) posts. For each post, participants could click share and/or like, or simply scroll past it if they did not wish to engage.

- Accuracy prompts increased the sharing of true relative to false news (as in past work) but did not affect “liking” of true versus false posts. Accuracy prompts also did not affect engagement with social posts.

- Adding colored borders to news posts increased engagement with news posts regardless of veracity while decreasing engagement with social posts.

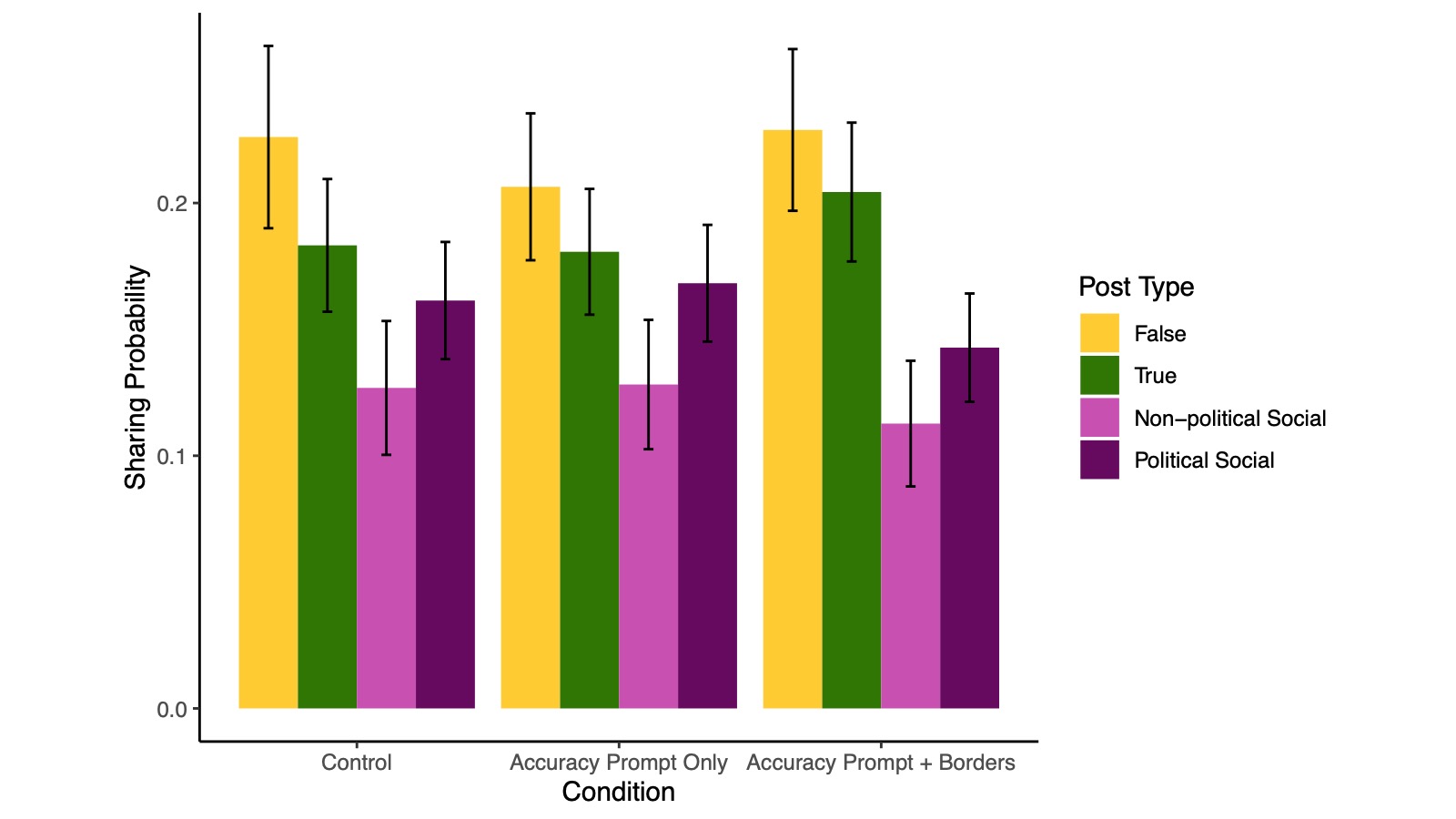

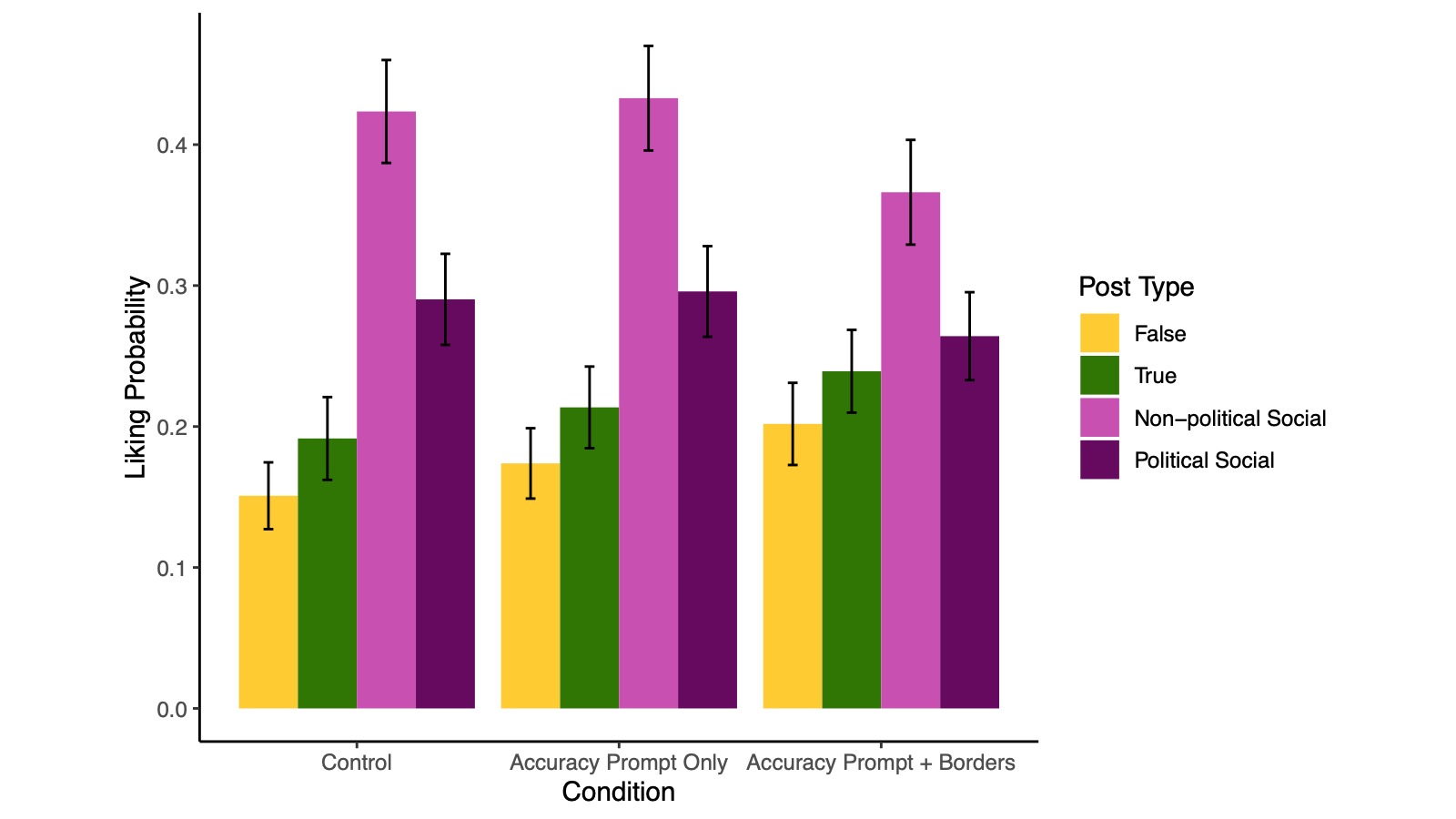

- We observed opposite patterns of engagement by type of social media post. False news headlines were shared the most, followed by true news headlines, then political social posts, and finally, non-political social posts. The opposite ordering was observed for liking posts, with non-political social posts being liked the most and false news posts liked the least.

- Our results suggest that accuracy prompts may improve sharing quality for accuracy-relevant news posts without impacting other forms of engagement (e.g., liking) or other types of online posts (e.g., social posts). Our findings also emphasize the importance of examining misinformation interventions in contexts containing different types of relevant social media content and allowing for different forms of user engagement.

Implications

The spread of misinformation on social media is a major contemporary academic and societal concern. For instance, false beliefs about voter fraud were rampant amongst Trump supporters following the 2020 U.S. presidential election (Pennycook & Rand, 2021), exposure to online misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines has decreased vaccination intent (Loomba et al., 2021), and misinformation on social media has been linked to increasing political cynicism (Lee & Jones-Jang, 2022). As a result, researchers and practitioners are interested in identifying and understanding interventions that social media platforms may employ to decrease belief and sharing of misinformation. One popular category of such interventions is pre-emptive strategies, such as general warnings or promoting media literacy (see Ecker et al., 2022 for review). Such pre-emptive strategies may be employed as lightweight user experience interventions. Further, technology companies may be more likely to adopt pre-emptive content-neutral strategies, in contrast with content-specific interventions (e.g., labels, removal, or downranking; see Saltz et al., 2021), as more general approaches may quell concerns over distrust or bias in selective fact-checking (e.g., Flamini, 2019).

A promising pre-emptive approach for increasing the quality of shared news content is providing users with prompts that shift attention to the level of accuracy of the content (Pennycook & Rand., 2022a, Pennycook & Rand, 2022b). Recent research suggests that individuals may sometimes share misinformation not purposefully but simply because they fail to consider the accuracy of the content before sharing (e.g., Pennycook et al., 2020; Pennycook et al., 2021b). Therefore, shifting the attention of individuals towards accuracy allows social media users to avoid sharing false content by prompting them to examine the veracity of the content before spreading it. Indeed, accuracy prompts and pausing to think about content before sharing it have been shown to increase news sharing quality both for political content (Fazio, 2020; Pennycook et al., 2021b) and COVID-19 information (Pennycook et al., 2020; for a meta-analysis, see Pennycook & Rand, 2022b). Accuracy prompt interventions have the additional benefits of being relatively quick and easy to implement—for instance, just asking individuals to evaluate the accuracy of one or several headlines has notable beneficial effects on improving sharing discernment (Epstein et al., 2021). Thus, accuracy prompts have the capacity to be more scalable than slower or more intensive approaches such as professional fact-checking (e.g., Stencel et al., 2021). Accuracy prompts may also be widely applicable across a variety of different social media platforms. For instance, similar types of prompts and reminders have been used on Facebook (encouraging users to read articles before sharing them; Ghaffary, 2021), Twitter (reminding users in the United States that election results may be delayed; Sherr, 2020), and Instagram (providing resources to information about the COVID-19 vaccine; Instagram, 2021). Interventions promoting consideration of accuracy may be deployed in similar ways on such platforms.

However, prior research on accuracy prompts leaves open several important unanswered questions. First, survey research assessing accuracy-prompt efficacy typically involves showing participants a series of only news headlines, shown one at a time (e.g., Epstein et al., 2021; Pennycook et al., 2021b). As a result, one open question is whether intermixing news with other types of non-news social media posts may impact the effect of accuracy prompts on news items, as well as whether accuracy prompts themselves may also impact the sharing of non-news posts (which would create a major disincentive for platforms to employ the prompts). Similarly, newsfeeds are typically scrollable and do not show posts one at a time—a more realistic survey experimental test of accuracy prompts should include this scrollable design in its setup (for side-by-side of typical single-item survey format versus a scrollable feed, see Appendix J, Figure S4; though note that we do not directly compare accuracy-prompt efficacy between single-item and scrollable presentations and just use the more realistic scrollable design in the current work). Another question is whether accuracy prompts may impact other forms of engagement on social media beyond sharing—for instance, “liking” of posts (as users may do on platforms such as Facebook or Twitter). As in Capraro and Celadin (2022), we utilize these latter two best-practice design choices of a scrollable newsfeed and multiple engagement options (sharing, liking) to examine these questions. Crucially, we then further build upon this design by incorporating non-news items into the simulated newsfeed.

We also examine whether a novel user experience intervention may further increase the efficacy of accuracy prompts—adding colored borders around news posts. One feature of accuracy prompts as an intervention is that they rely on people having some preexisting ability to recognize when accuracy is relevant to a post—for instance, accuracy is relevant when deciding whether to share a news post but is perhaps less relevant to consider when deciding whether to share a non-news post from a friend. Since individuals’ information diets consist of more non-news than news content in general (Allen et al., 2020), it may be advantageous to visually indicate when online content is accuracy-relevant, particularly since categorizing news from non-news content can be difficult (see Vraga et al., 2016). Such visual explicit categorization may be specifically helpful in conjunction with the use of accuracy prompts.

One simple way to employ visual distinction between news and non-news content is by applying colored borders around news content—indeed, research suggests that the majority of individuals’ assessments of people or products may be based on colors alone (Singh, 2006)—indicating that color differentiation may be a fast and effective way to distinguish news from non-news content in a social media setting. Colors are often used to communicate abstract information or concepts, and people have been shown to make inferences from color coding systems when making judgments and decisions offline (e.g., deciding which unlabeled but colored bin to recycle in; Schloss et al., 2018). Color coding and border systems have also been incorporated in online spaces: for example, different types of labels and borders have been used to distinguish ads and paid content from other posts on newsfeeds and in search engine results (Johnson et al., 2018); green circles around Instagram stories denote stories from close friends relative to standard reddish-orange circles (Johnson, 2022); and Reddit posts and comments that have received awards are highlighted with a colored background and orange border (Reddit, 2021). Prior research also suggests color differences may have meaningful impacts on outcomes such as click rates (Jalali & Papatla, 2016) and sharing (Can et al., 2013). Altogether, we aim to further existing research and application of color-concept borders by examining the effects of news borders and whether they may affect the efficacy of interventions relying on recognizing the relevance of accuracy.

Here, we advance research on accuracy prompt interventions by assessing how well accuracy prompts work in a more realistic survey environment—namely, one that (a) simulates a scrollable newsfeed, (b) allows for both sharing and liking of content, and (c) includes social, non-news posts. We also test whether accuracy prompts may be even more effective when combined with adding colored borders around news posts to distinguish them from social posts.

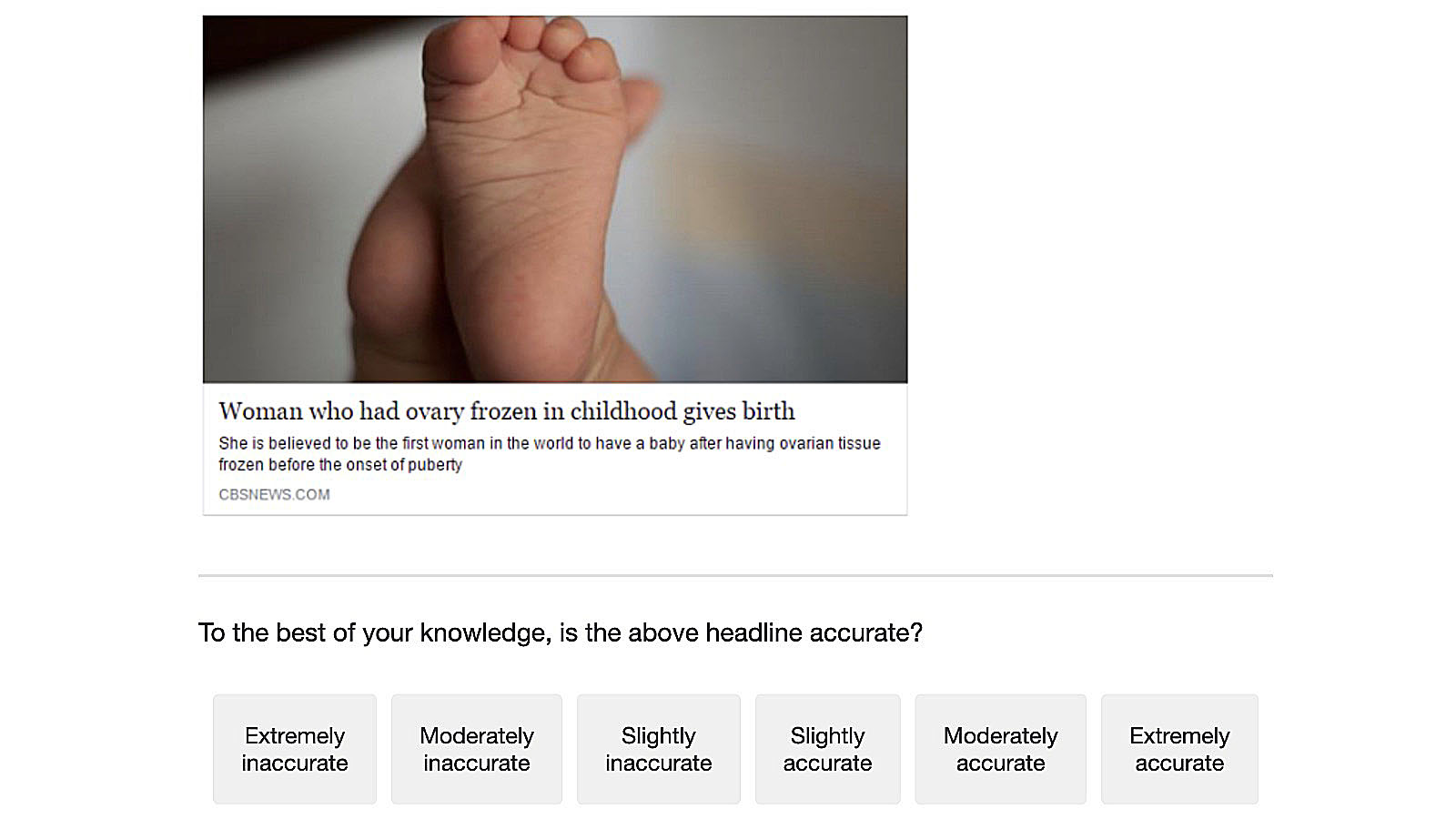

In particular, we examined the effectiveness of an accuracy prompt where prior to being shown a newsfeed, participants were asked to evaluate the accuracy of a single news headline randomly chosen from one of four possible non-political news headlines on a scale of 1 to 6 (1 = “Extremely inaccurate,” 6 = “Extremely accurate;” see Figure 6). This design has been utilized in previous work on accuracy prompts (e.g., Epstein et al., 2021; Pennycook et al., 2021b) to help shift attention to the concept of accuracy before participants continue to a news-sharing or engagement task. This style of accuracy prompt has also been implemented and tested in actual social media environments—prior work directly messaged users on Twitter asking about the accuracy of single non-political news headlines and found that these messages increased the quality of subsequent news sharing on the platform (see Pennycook et al., 2021b, Study 7). In broader practice, platforms could periodically ask users to rate content while online: for example, when users first sign in, they could be asked to rate the accuracy of a piece of content before scrolling on their feed. Alternatively, users could be provided with an in-feed accuracy evaluation task if they are about to view lower-quality content.

In the current work, we compared three different conditions—a control condition with no interventions, an accuracy-prompt-only condition with just an accuracy prompt, and an accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition with an accuracy prompt and purple borders around news posts. We then assessed the effectiveness of the treatments (relative to the control) on participants’ propensity to share and like different types of online content. Consistent with prior research, we found that providing participants with an accuracy prompt increased the quality of news content participants shared. Encouragingly, we did not find an effect of accuracy prompts on sharing of social (non-news) posts. We also did not find an effect of accuracy prompts on liking news (consistent with Capraro & Celadin, 2022) or non-news posts. These findings suggest that accuracy prompts may help increase the amount of true relative to false news shared by shifting users’ attention to accuracy when making decisions about spreading news content online. Further, our results provide evidence that accuracy prompts may not affect decisions to share posts for which accuracy is less important or irrelevant (e.g., social posts). We also find that accuracy prompts may particularly impact sharing decisions, rather than engagement decisions that may be more about expressing affect or agreement (e.g., liking) than further disseminating news content via sharing.

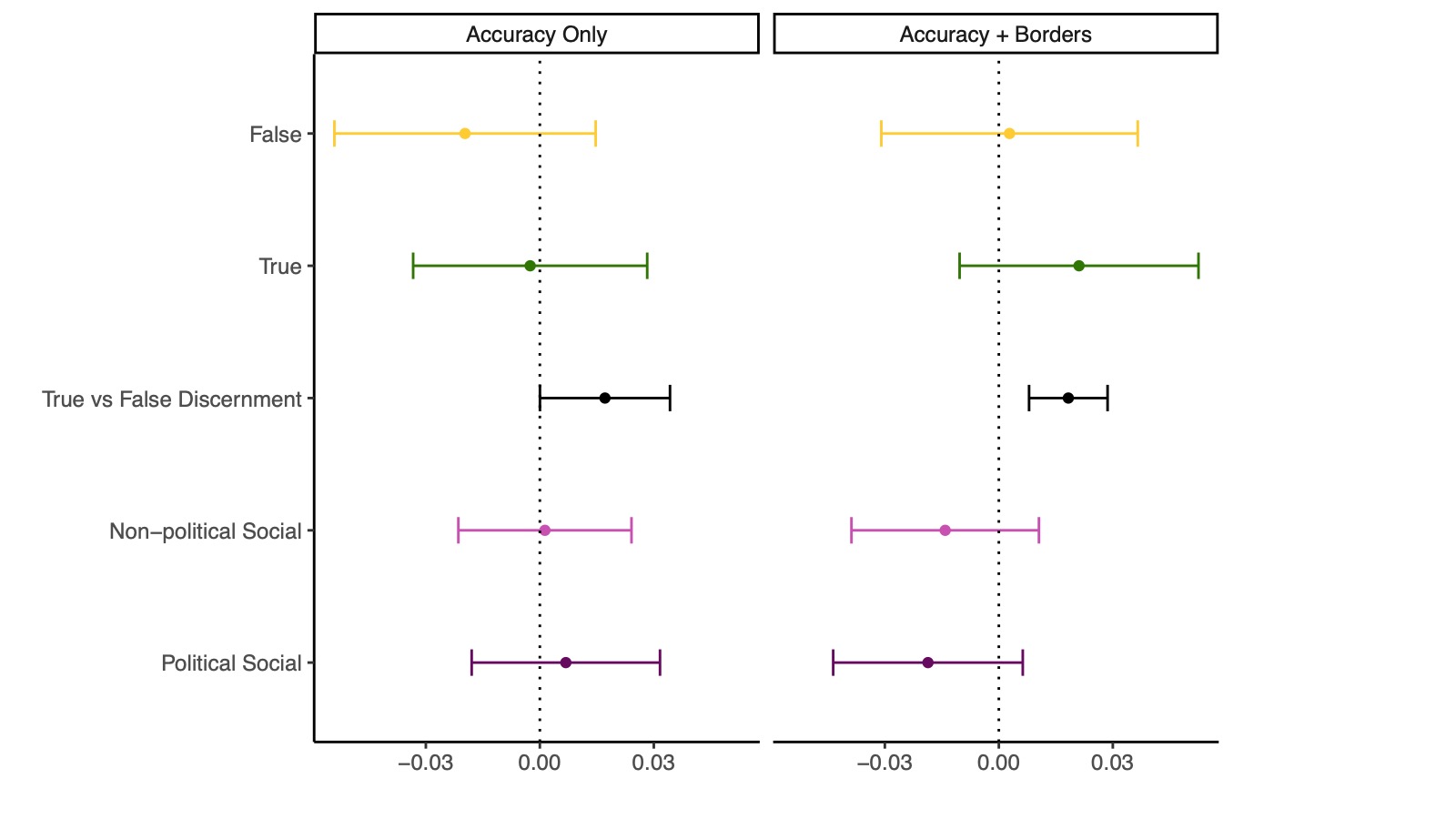

Next, our findings did not provide evidence that adding colored borders around news posts improved the ability of accuracy prompts to increase the quality of news shared—both interventions increased the amount of true news relative to false news shared. Interestingly, however, our interventions may have improved sharing discernment (i.e., sharing of true versus false news) via different mechanisms—the accuracy-prompt-only condition primarily decreased false sharing relative to control, whereas the accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition increased true sharing relative to control.

More broadly, we found that the addition of colored borders around news posts increased sharing and liking of both true and false news posts and decreased engagement with social, non-news posts. This may be due to the colored borders increasing attention to both true and false news posts (relative to non-news posts), without further reinforcing accuracy considerations. Although not a primary focus of our study, we also found strikingly distinct patterns of engagement across the different types of posts in our study. False news posts were shared the most, followed by true news posts, then political social posts, and finally, non-political social posts. In stark contrast, we found the opposite engagement pattern for liking, such that non-political social posts were liked the most and false news posts were liked the least. Such patterns could reflect distinct engagement norms by content type on social media.

Our findings have several important practical implications for practitioners and researchers examining misinformation interventions. First, in concert with prior research, we demonstrate that accuracy prompts can increase the quality of news sharing in a simulated social media setting. Of note, our findings also suggest that accuracy prompts are still effective in a scrollable newsfeed setting; and are also effective even when the majority of participants’ newsfeeds are non-news posts. These results should help ease concerns over whether accuracy prompts may be severely limited in contexts where news posts are less frequent or viewed with lower attentiveness.

Second, our findings suggest that accuracy prompts do not appear to generally affect engagement with social, non-news posts, which may be beneficial to social media platforms that likely would hesitate to deploy interventions that only decrease misinformation sharing at the expense of also decreasing non-news or social post engagement.

Third, we found that applying colored borders to news posts increased engagement with these posts regardless of whether the news was true or false and decreased engagement with non-bordered social posts. It may be the case that the colored borders increased attention and dwell time to news posts, which in turn increased the probability of engagement regardless of veracity. Such would be consistent with a “Try + Buy” model of newsfeed engagement, such that engagements with posts are conditional on exposure, and attention-grabbing borders may uniformly increase exposure in the initial “try” phase (see Lin et al., 2022). Future work may examine whether adding colored borders does indeed increase dwell time on such posts. Alternatively, it could be that purple borders, in particular, increased engagement. In a pretest pilot study, we did not find any significant differences in sharing, liking, or engagement of news posts with purple versus green colored borders. Nonetheless, subsequent studies may still further examine whether different colors around news or non-news posts may result in different engagement patterns. Practically, our findings overall suggest that simply drawing attention to news posts, even in combination with an accuracy prompt, does not help improve the quality of news content engaged with and has the additional consequence of drawing attention away from posts without a colored border.

Finally, our descriptive findings that different types of posts were engaged with in distinctly different ways demonstrate the importance of considering multiple relevant dimensions of a social media feed when testing design interventions—for instance, examining different types of engagement (liking, sharing) and different categories of online posts (true news, false news, political social, non-political social).

Altogether, our results help to inform social media platforms, policymakers, and misinformation researchers about the efficacy of accuracy prompts in more realistic simulated newsfeed environments. Our findings also provide meaningful insight into the effects of visual differentiation interventions and underscore the importance of examining the interplay between complementary online platform features.

Findings

Finding 1: Accuracy prompts increased sharing discernment but did not affect liking discernment or engagement with non-political social posts.

We predict whether participants share a given post by post type (false news, true news, non-political social, political social), condition (control, accuracy-only, accuracy-plus-borders), and their interaction—with robust standard errors clustered by participant and post. In this section, we will first discuss our results for the accuracy-prompt-only condition.

We predict whether participants share a given post by post type (false news, true news, non-political social, political social), condition (control, accuracy-only, accuracy-plus-borders), and their interaction—with robust standard errors clustered by participant and post. In this section, we will first discuss our results for the accuracy-prompt-only condition.

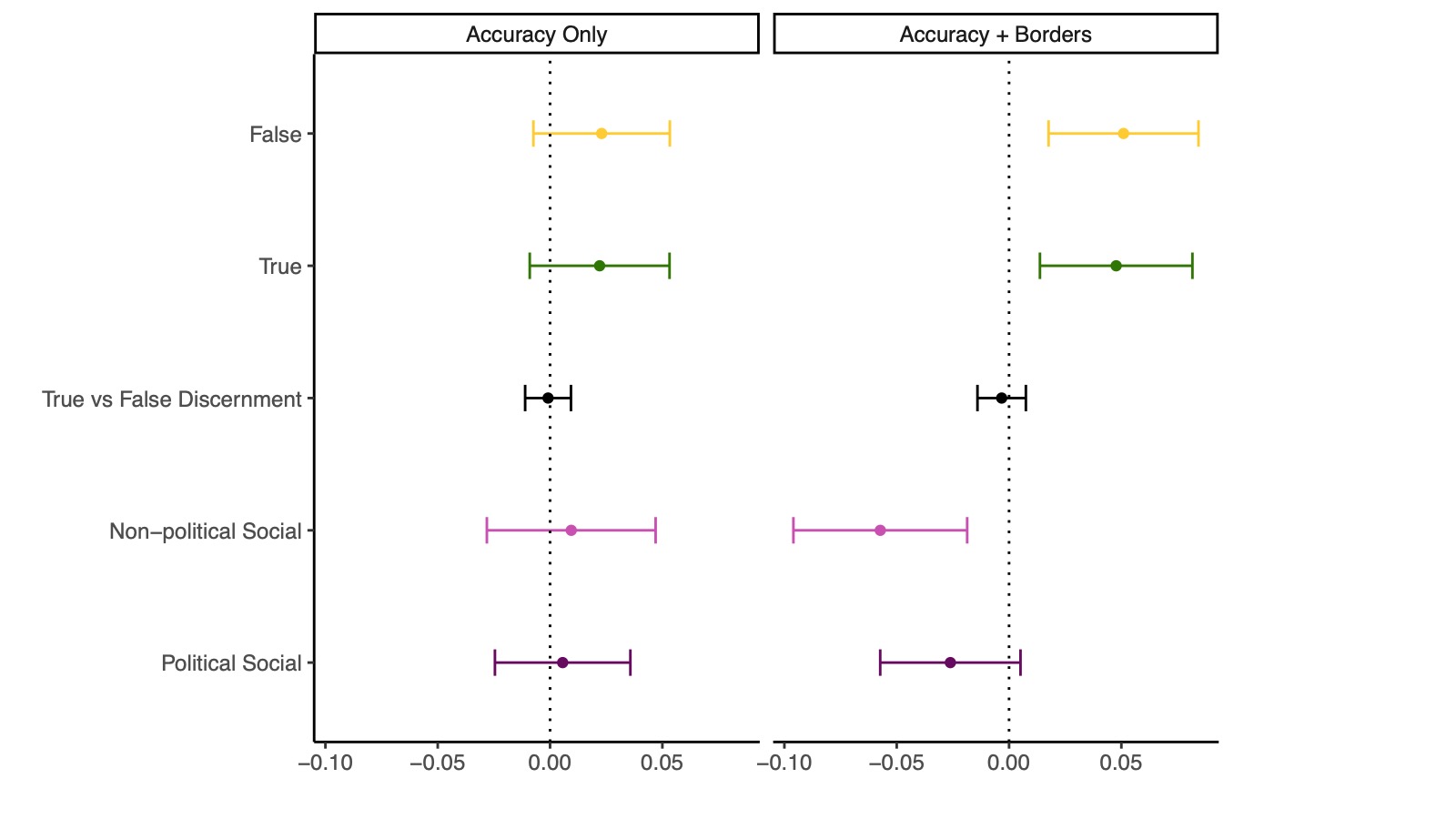

Consistent with previous research, we found that the accuracy-prompt-only condition increased sharing of true relative to false news (b = .017, SE = 0.009, p = .05; see Figure 1, Figure 2; Appendix C, Table S3). Throughout this section, sharing, liking, and engaging are always 0 (did not engage) to 1 (engaged); therefore, b estimates may be interpreted as the effect size in terms of percentage points. For example, the accuracy-prompt-only condition effect size on increasing true relative to false news sharing of b = .017 may be interpreted as accuracy prompts increasing true sharing (relative to false sharing) an additional 1.7 percentage points. Investigating this effect further, our results show that the accuracy-prompt-only condition decreased false news sharing 8.8% relative to the control condition. Such reductions in false news sharing also may have considerable downstream network effects in preventing the beginning and continuation of rumor cascades, whereby false stories are continually reshared on social networks (Friggeri et al., 2014). That being said, accuracy prompts should be considered one of many tools best used in conjunction with one another for mitigating the spread of online misinformation (see Bode & Vraga, 2021).

We next performed a similar analysis, except predicting liking rather than sharing of posts. Here, we did not find evidence that the accuracy-prompt-only condition increased liking of true relative to false news (b = -.001, SE = 0.005, p =.865; see Figure 3, Figure 4; Appendix C, Table S7).

When predicting overall engagement (i.e., whether participants shared or liked a post), we found that the accuracy-prompt-only condition did increase overall engagement with true versus false news (b = .017, SE = 0.008, p = .037; Appendix C, Table S11).

We also examined potential moderation of our treatment condition effects by participant partisanship (1 = “Strongly Democratic,” 6 = “Strongly Republican”) and political concordance between participant and post (for news posts pre-tested as pro-Democrat or pro-Republican, and for political social posts designed as pro-Democrat or pro-Republican), although we are likely underpowered to detect these 3-way and 4-way interactions. Thus, while we did not find clear evidence that partisanship, political concordance, nor the interaction of the two moderated the accuracy-prompt-only effect on sharing, liking, or engagement discernment between true and false news posts (ps > .051; Appendix F, Tables S24–S26), future work should investigate these issues in more detail.

As pre-registered, we also examined the effect of accuracy prompts after collapsing across our two treatment conditions. Here we find even clearer evidence of accuracy prompt treatments increasing sharing of true relative to false news (b = .018, SE = 0.007, p = .009; Appendix E, Table S21). Relative to baseline, we find that our combined treatment decreases false news sharing by 3.5% and increases true news sharing by 5.5%. We again do not find evidence that accuracy prompts affect liking of true versus false news (b = -.002, SE = 0.005, p = .661; Appendix E, Table S22).

We also assessed the effect of accuracy prompts on social (non-news) posts. For both non-political and political social posts, we did not find evidence that the accuracy-prompt-only condition affected sharing, liking, or overall engagement (ps > .429 and .459, respectively; also see Figure 2, Figure 4).

Finding 2: Adding colored borders around news content does not increase the efficacy of accuracy prompts—but does increase engagement with news posts and decrease engagement with social posts.

We will now discuss our results for the accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition. Like in the above analyses, we found that the accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition increases the sharing of true versus false news (b = .018, SE = 0.005, p = .001; Appendix C, Table S3). We did not find evidence that this treatment increased the liking of, or overall engagement with, true versus false news (ps > .111; Appendix C, Tables S7 and S11). We also examined whether participant partisanship, post-political concordance, or the interaction of the two moderated our accuracy-prompt-plus-borders effects on engagement discernment between true and false news. We did not observe any statistically significant moderation of sharing, liking, or engagement discernment, with one exception: we found some evidence that the accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition increased engagement with true posts (relative to false posts) on politically concordant posts for more Republican participants (p = .035; for full analyses, see Appendix F, Tables S24–26). However, due to lack of statistical power for detecting these high-order interactions, all of these results should be interpreted with caution.

Next, we compared effects between the accuracy-prompt-only condition and the accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition. We examined whether the addition of colored news borders increased the efficacy of accuracy prompts—that is, we test whether adding colored borders increases sharing or engagement discernment above and beyond the increase from just providing accuracy prompts without news borders. We conducted Wald tests comparing the effects of the accuracy-prompt-only condition and accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition on increasing sharing of true relative to false news. For sharing, liking, and overall engagement, we did not find a significant difference between these two conditions on increasing true versus false news sharing (ps > .578; see Appendix C, Tables S4, S8, and S12), suggesting that colored borders around news posts did not improve accuracy-prompt effectiveness. However, we did nominally find that the accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition appeared to improve sharing discernment by increasing the amount of true news shared relative to control, whereas the accuracy-prompt-only condition improves sharing discernment by primarily decreasing the amount of false news shared relative to control (see Figure 2).

We then assessed the effects of colored news borders on sharing, liking, and overall engagement with news and social posts. Combining news posts across veracity (true and false news, together), we found that colored news borders increased sharing, liking, and overall engagement with news posts, regardless of veracity (p < .011; Appendix C, Tables S5, S9, and S13). Similarly, we also examined whether colored news borders impacted engagement with social posts (collapsing across political and non-political social posts). We found that news borders reduced liking of and overall engagement with social posts (ps < .001; Appendix C, Tables S10 and S14). We also find that news borders nominally, though non-significantly, reduce sharing of social posts as well (p = .212; Appendix C, Table S6). Figures 1 and 3 both show that relative to the accuracy-prompt-only condition, news posts were shared and liked more in the accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition; and that social posts were shared and liked less in the border condition.

Finding 3: Participants exhibit opposite patterns of sharing and liking by category of social media post.

Across our main analyses, we observed distinct patterns of engagement by sharing or liking, and by the category of social media post. In this final section, we will discuss sharing and liking rates focusing only on our control condition. As an exploratory analysis, we assessed relative levels of sharing and liking by post category in our control condition. We used a linear model to predict sharing by post type, with cluster-robust standard errors by participant and post. We found that false news posts were shared the most (b = .226, p < .001). True news posts were shared second most, but significantly less than false news posts (b = -.043, p = .009). Political social posts were shared third most, nominally (but not significantly) less than true news posts (b = -.022, p = .085). Non-political social posts were shared the least, significantly less than political social posts (b = -.035, p = .016; also see Figure 1; Appendix D, Tables S15–S17).

Compared to prior survey experimental research on true versus false news sharing intentions, it is atypical that we find false news shared at higher rates than true news (typically, true news is shared more than false news; though this difference is not as great as when assessing accuracy judgments between true and false news, see Figure 1 in Pennycook et al., 2021b). One possible reason for this is that participants differentially substituted “liking” for “sharing” on true news posts—that is, given the opportunity to share and/or like a post, participants who typically may have shared true posts if only given the opportunity to share may have opted to “like” these headlines, while participants who typically share false headlines continued to select the share option. Another potential explanation is that several false news posts, in particular, were responsible for inflating the sharing rate of false news overall. This is plausible given only a moderately sized news headline set (24 items). We investigated exploratorily whether this was the case—descriptively, we found in our control condition that only two news posts had share probabilities over 30%—and both were false headlines (one COVID-related, one pro-Republican). Notably, the next two most shared posts (27.5% and 27.2%, respectively) were also false headlines (COVID-related). Other than those four posts, no other headline (true or false) was shared over 25% of the time (see Appendix J, Figure S3). If we were to remove the two news posts shared over 30% of the time from our previous analysis, the difference between false and true news sharing in the control condition is no longer significant (b = -.027, p = .059). Thus, although we do find that false news headlines were shared more than true news headlines in the current work, it seems tentatively plausible that this is due to a small number of highly shared false headlines—and that after removing these headlines, differences between false and true news sharing in our data are largely in line with previous work.

We also performed similar analyses predicting liking by post type. Interestingly, we found an opposite pattern of liking versus sharing by post category. False news posts were liked the least (b = .151, p < .001). True news posts were liked the second least, and significantly more than false news posts (b = .041, p < .001). Political social posts were liked significantly more than true news posts (b = .099, p < .001), and non-political social posts were liked the most of any post category, significantly more so than political social posts (b = .133, p < .001; also see Figure 3; Appendix D, Tables S18–S20).

Methods

From August 1 to August 7, 2022, a total of 2,103 participants began our study, passed a trivial attention check (e.g., captcha item), and provided informed consent. Of these individuals, 1,524 participants at least began the main newsfeed task of the survey (Mage = 46.6, 50.5% female, 72% White-only; see Appendix A). We performed a chi-square test to determine whether there was differential attrition between the control and treatment conditions for individuals reaching the newsfeed part of the survey. We did not find evidence for differential attrition (p = .133; Appendix B).

Participants were recruited via Lucid, a survey platform aggregator that uses quota sampling in an effort to match the U.S. distribution on age, gender, race, and geographic region. We pre-registered our experiment here. Pre-registered analyses not reported in this main text are available in the Appendix.

Participants were only invited to begin the survey if they reported having either a Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram account. Participants were then given a single captcha item; those who failed this captcha were told they were ineligible for the current study and were not allowed to continue the survey. Participants first completed basic demographics questions (e.g., age, gender, race). Throughout the survey, participants were also given three attention check items (two pre-treatment, one post-treatment; items from Berinsky et al., 2021). Participants who answered these items incorrectly were still included in the survey (see Appendix H for pre-registered secondary analyses omitting participants who failed both pre-treatment attention items). Next, participants were instructed that their main task would be to imagine they were scrolling through social media and to share, like, or scroll past headlines in a newsfeed.

Prior to the main task, participants were then instructed to complete a practice headline set in order to get used to the survey structure, which included a scrollable newsfeed and clickable share and like buttons (styled after Facebook’s engagement options). In the practice, participants were given three practice headlines and were asked to like the first post, skip the second post, and share the third post. If participants incorrectly engaged with any of these headlines, they were given the practice prompt a second time. Overall, 83% of participants passed the practice by their second attempt. Participants who failed both attempts were still included in the survey (see Appendix G for pre-registered secondary analyses omitting participants who never correctly answered these practice items).

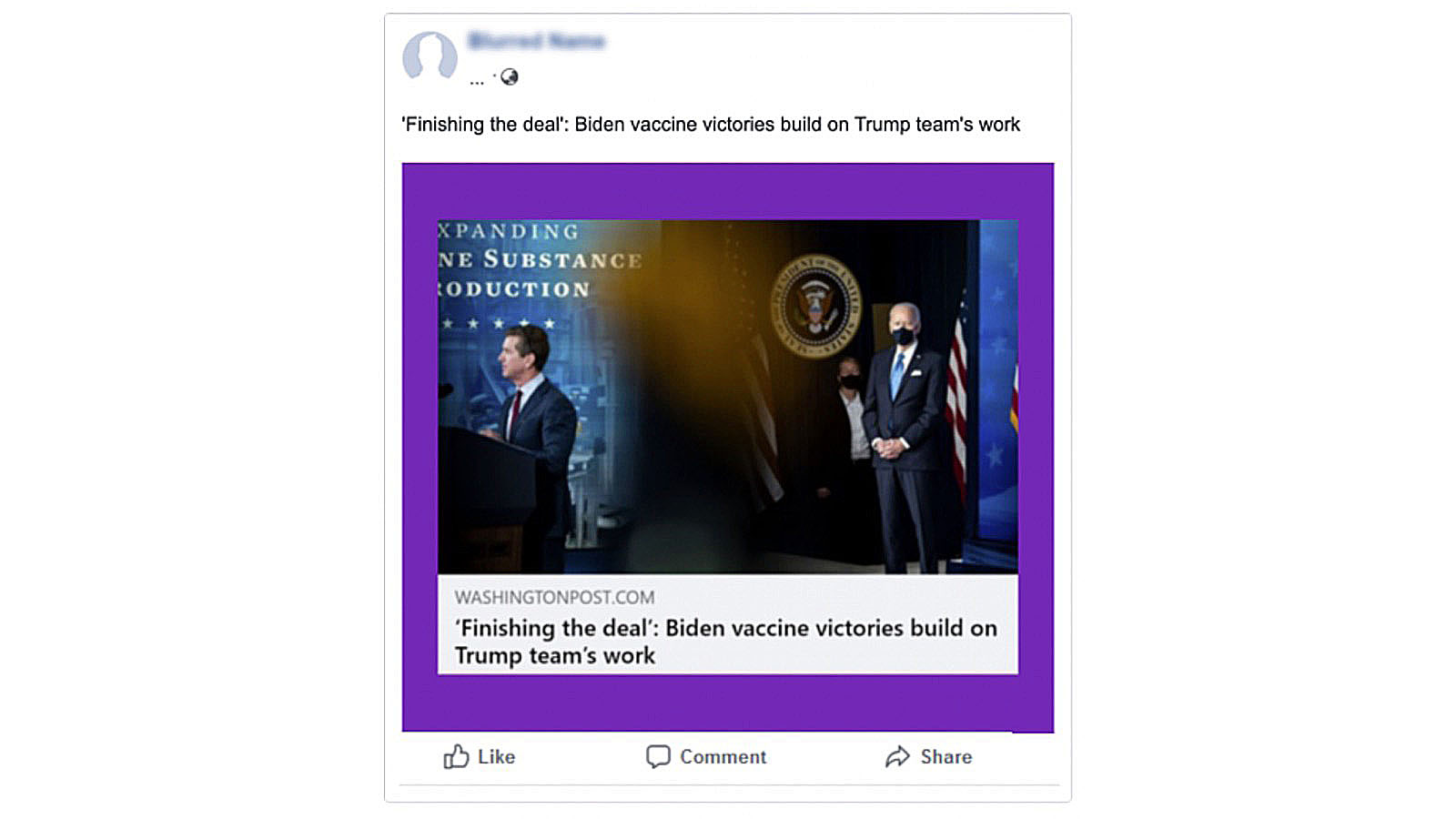

Participants were then randomly assigned to one of three conditions: accuracy-prompt-only (accuracy prompt), accuracy-prompt-plus-borders (accuracy prompt plus purple borders around news posts, no borders around social posts; see Figure 5 for an example of purple-colored border), or control (no accuracy prompt or colored news borders). Purple-colored borders were chosen after we did not find any reliable differences during initial pretesting between purple and green borders on news content (N = 209; sharing: b = -.085, p = .085; liking: b = -.020, p = .683; engagement: b = -.063, p = .295). We also chose purple because it does not have a pre-existing color-concept affiliation with a particular U.S. political party (whereas blue is associated with Democrats and red with Republicans). Future work may examine whether our findings generalize to other content border colors. Another potential limitation of our border design is its size and obtrusiveness. We aimed to make the borders clearly distinguishable and able to attract the attention of participants, perhaps sacrificing a degree of ecological validity regarding its overall aesthetics. That being said, comparable colored borders have been used on prominent social media platforms—for instance, colored circles around Instagram stories (Johnson, 2022) and colored squares and highlights for awarded Reddit comments and posts (Reddit, 2021).

Participants were next given instructions indicating that the newsfeed they were going to be shown had two types of content: informational/news articles and social/personal posts. If they were in the accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition, these instructions also established that as a new platform feature to help differentiate content, informational/news articles would have a purple border around them.

Then, participants in the treatment conditions were given an accuracy prompt. Participants were asked to evaluate the accuracy of a single news headline randomly chosen from one of four possible headlines on a scale from 1 = “Extremely inaccurate” to 6 = “Extremely accurate” (see Figure 6). Headlines in the accuracy-prompt-plus-borders condition additionally had a purple border around them.

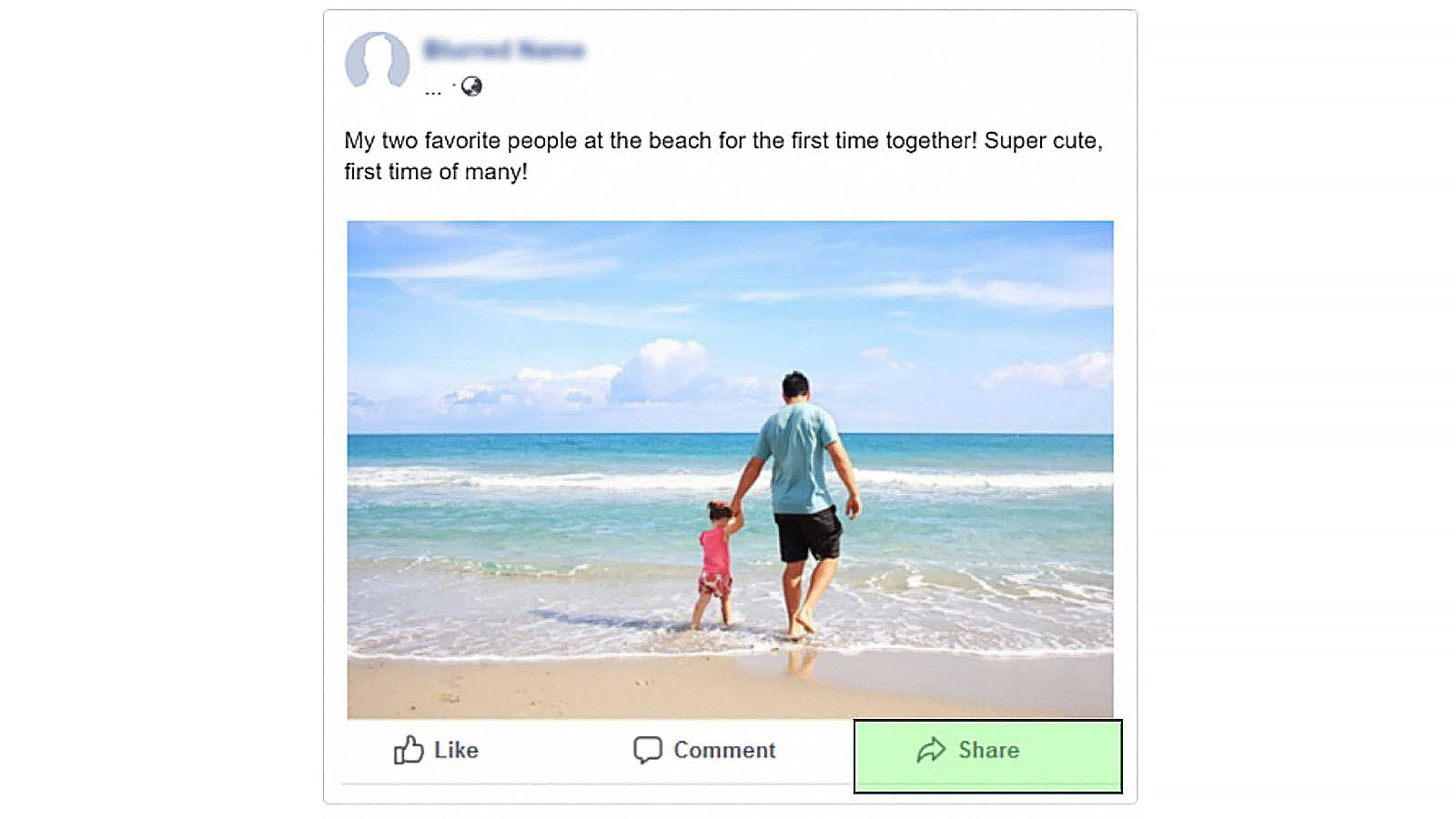

Participants were finally given the main newsfeed task of the survey. Participants were shown 72 posts on the same scrollable page, presented in random order. Twenty-four posts were news article headlines, and 48 posts were social posts. Of the 24 news posts, half were true and half were false; additionally, a quarter were pro-Democratic party, a quarter were pro-Republican party, a quarter were COVID-related, and a quarter were COVID-vaccine-related. Of the 48 social posts, half were apolitical social posts. The other half were political social posts—half pro-Democratic party and half pro-Republican party. News article posts were selected from actual news headlines—real headlines were selected from reliable mainstream news organizations, and false headlines were selected from articles evaluated as false by third-party professional fact checkers (see Pennycook et al., 2021a for an overview of the selection process). Pro-Democratic party and Pro-Republican party news headlines were pre-tested prior to this study, and the set we use in our current work was built to closely match on relevant features such as likelihood, importance, and anticipated sharing (pre-test data available here). Non-news posts were artificially developed for the purposes of the current work, as we did not want to use actual personal non-news posts for privacy reasons. Non-news articles were constructed by finding royalty-free images via online databases (e.g., https://unsplash.com/). Political social posts were not pre-tested – however, we do verify that in the current work, politically concordant social posts were shared (b = .041, p < .001), liked (b = .081, p < .001), and overall engaged with (b = .101, p < .001) more than politically discordant social posts. Participants were not explicitly instructed as to whether the news and non-news posts they would see actually came from social media; participants were just instructed to act as though they were actually on their own social media feed. See Figure 5 for a news post example, Figure 7 for a social post example, and Appendix J, Table S42 for examples of each category of post.

For each post, participants could “share” and/or “like” the item by clicking the appropriate button (see Figure 7). Participants could also scroll past a post if they did not want to engage with it. Participants were not allowed to advance from the main newsfeed page for at least two minutes.

At the end of the survey, participants were asked their political preferences (1 = “Strongly Democratic,” 6 = “Strongly Republican;” see Appendix F for pre-registered secondary analyses including partisanship and post-political concordance as potential moderators) and completed an affective polarization feeling thermometer about attitudes towards Republican and Democratic party voters. All study materials, data, and analysis code are available here and here.

Topics

Bibliography

Allen, J., Howland, B., Mobius, M., Rothschild, D., & Watts, D. J. (2020). Evaluating the fake news problem at the scale of the information ecosystem. Science Advances, 6(14), eaay3539. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay3539

Aronow, P. M., Kalla, J., Orr, L., & Ternovski, J. (2020). Evidence of rising rates of inattentiveness on Lucid in 2020. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/8sbe4

Berinsky, A. J., Margolis, M. F., Sances, M. W., & Warshaw, C. (2021). Using screeners to measure respondent attention on self-administered surveys: Which items and how many? Political Science Research and Methods, 9(2), 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.53

Bode, L. & Vraga, E. (2021). The Swiss cheese model for mitigating online misinformation. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 77(3), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2021.1912170

Can, E. F., Oktay, H., & Manmatha, R. (2013, October). Predicting retweet count using visual cues. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM international conference on information & knowledge management (pp. 1481–1484). Association for Computing Machinery. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2505515.2507824

Capraro, V., & Celadin, T. (2022). “I think this news is accurate”: Endorsing accuracy decreases the sharing of fake news and increases the sharing of real news. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672221117691

Coppock, A., & McClellan, O. A. (2019). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research & Politics, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018822174

Ecker, U. K., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., Kendeou, P., Vraga, E. K., & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

Epstein, Z., Berinsky, A. J., Cole, R., Gully, A., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Developing an accuracy-prompt toolkit to reduce COVID-19 misinformation online. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-71

Fazio, L. (2020). Pausing to consider why a headline is true or false can help reduce the sharing of false news. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-009

Flamini, D. (2019, July 3). Most Republicans don’t trust fact-checkers, and most Americans don’t trust the media. Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/ifcn/2019/most-republicans-dont-trust-fact-checkers-and-most-americans-dont-trust-the-media/

Friggeri, A., Adamic, L., Eckles, D., & Cheng, J. (2014, May). Rumor cascades. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 8(1), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v8i1.14559

Ghaffary, S. (2021, May 10). Facebook will push you to read articles before you share them. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2021/5/10/22429240/facebook-prompt-users-read-articles-before-sharing

Instagram. (2021, March 16). Helping people stay safe and informed about COVID-19 vaccines. https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/continuing-to-keep-people-safe-and-informed-about-covid-19

Jalali, N. Y., & Papatla, P. (2016). The palette that stands out: Color compositions of online curated visual UGC that attracts higher consumer interaction. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 14(4), 353–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-016-9178-1

Johnson, D. (2022, July 9). What does a green outlined ring mean for Instagram stories? Alphr. https://www.alphr.com/instagram-stories-green-circle/

Johnson, J., Hastak, M., Jansen, B. J., & Raval, D. (2018, April). Analyzing advertising labels: Testing consumers’ recognition of paid content online. In CHI EA ’18: Extended abstracts of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–6). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3170427.3188533

Lee, S., & Jones-Jang, S. M. (2022). Cynical nonpartisans: The role of misinformation in political cynicism during the 2020 U.S. presidential election. New Media & Society, 14614448221116036. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221116036

Lin, H., Epstein, Z., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. (2022). Quantifying attention via dwell time and engagement in a social media browsing environment. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2209.104

Loomba, S., de Figueiredo, A., Piatek, S. J., de Graaf, K., & Larson, H. J. (2021). Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(3), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1

Pennycook, G., Binnendyk, J., Newton, C., & Rand, D. G. (2021a). A practical guide to doing behavioral research on fake news and misinformation. Collabra: Psychology, 7(1), 25293. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.25293

Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A. A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021b). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature, 592(7855), 590–595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03344-2

Pennycook, G., McPhetres, J., Zhang, Y., Lu, J. G., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychological Science, 31(7), 770–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620939054

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Examining false beliefs about voter fraud in the wake of the 2020 Presidential Election. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-51

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2022a). Nudging social media toward accuracy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 700(1), 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162221092342

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2022b). Accuracy prompts are a replicable and generalizable approach for reducing the spread of misinformation. Nature Communications, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30073-5

Reddit. (2021). What are awards and how do I give them? https://reddit.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/360043034132-What-are-awards-and-how-do-I-give-them-

Saltz, E., Barari, S., Leibowicz, C., & Wardle, C. (2021). Misinformation interventions are common, divisive, and poorly understood. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(5). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-81

Schloss, K. B., Lessard, L., Walmsley, C. S., & Foley, K. (2018). Color inference in visual communication: the meaning of colors in recycling. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-018-0090-y

Sherr, I. (2020, October 26). Twitter adds prompts to remind you presidential election results may be delayed. CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/politics/twitter-adds-prompts-to-remind-people-presidential-election-results-may-be-delayed/

Singh, S. (2006). Impact of color on marketing. Management Decision, 44(6), 783–789. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740610673332

Stencel, M., Luther, J., & Ryan, E. (2021, June 3). Fact-checking census shows slower growth. Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2021/fact-checking-census-shows-slower-growth/

Vraga, E. K., Bode, L., Smithson, A. B., & Troller-Renfree, S. (2016). Blurred lines: Defining social, news, and political posts on Facebook. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(3), 272–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2016.1160265

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Reset Initiative of Luminate, the John Templeton Foundation, and the TDF Foundation. C.M. is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (Grant No. 174530).

Competing Interests

Other research by D.G.R. is funded by gifts from Google and Meta.

Ethics

Our study was approved with a waiver of informed consent by the MIT Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects Protocol E-2443. We report race and gender categories, with options defined by the investigator (for full options, see full survey materials here: https://osf.io/vp6m7/?view_only=60c943a8959240cf8d509d39baeba568). These categories were included in the study in order to investigate heterogeneity in misinformation intervention efficacy in future research.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BQUFBR and OSF: https://osf.io/vp6m7/?view_only=60c943a8959240cf8d509d39baeba568

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Antonio Arechar for assistance with data collection.

Authorship

Venya Bhardwaj and Cameron Martel contributed equally to this work.