Peer Reviewed

Does incentivization promote sharing “true” content online?

Article Metrics

4

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

In an online experiment in India, incentives for sharing factual posts increased sharing compared to no incentivization. However, the type of incentive (monetary or social) did not influence sharing behavior in a custom social media simulation. Curbing misinformation may not require substantial monetary resources; in fact, social media platforms can devise ways to socially incentivize their users for being responsible netizens who share true information. Results of the study point to the need for further analysis through real-world experiments on how effective social incentivization systems can be put in place.

Research Questions

- Do social or financial incentives affect the likelihood of sharing content?

- Does additional information beyond a headline affect the decision to share a post?

- Do different types of post content elicit different socio-emotional reactions (measured through emojis)?

Essay Summary

- In this experiment, a mock social media platform was created to understand if incentivizing participants to share factual content and disincentivizing the sharing of misinformation influenced their sharing behavior on the platform.

- Participants (N = 908) were shown posts that they could share, react to (using emojis), or choose ‘read more’ to get more information. Participants were divided into two groups where they received either micropayments (financial incentive group) or followers (social incentive group) incentives for each true message they shared; similarly, they were disincentivized (lost money/followers) for sharing false information.

- Results showed that incentivization, regardless of the type, encouraged people to share more true information; however, the two incentivized groups did not differ in their sharing behavior, for all types of posts.

- Older individuals, those with more education, and those with a right-leaning political ideology were more likely to share posts, with the latter being more likely to react to posts as well.

- No gender differences were seen in sharing behavior.

Implications

The online information ecosystem is influenced by what news gets shared, which has significant implications for people’s behavior and can manipulate their implicit emotions and attitudes (Hudson et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2021). Sharing information gives people confidence and makes them feel more informed and knowledgeable (Bastick, 2021). However, freedom to create and share information can lead to proliferation of misinformation (Safieddine et al., 2017) and distortion of reality (Flaxman et al., 2016). False news is seen to spread much faster and farther, and is found to be more novel than true news (Vosoughi et al., 2018), suggesting that people are more likely to share novel information. Friggeri et al. (2014) found that rumor cascades (content shared by multiple users independently) run deeper in social networks than reshare cascades in general. These findings suggest that online spaces are fraught with false information that is likely to spread at a faster rate than factual information.

Against this background, any attempt to reconceptualize the Internet requires reviewing incentives, not only for content creation but also for content discovery and amplification. Such incentives can be financial (real money or tokens) and social (engagement via likes, followers, shares, etc.). In countries like India, content is amplified in closed messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp), even in the absence of platform-enabled amplification (Mitra, 2020), and the lack of centralized moderation makes information consumers the primary line of defense against low-quality information. With WhatsApp’s ability to sow misinformation easily in this manner, it has attracted attention from researchers focusing on the Global South (Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania) where this app is popularly used. In Brazil, where WhatsApp is a popular mode of communication, Resende et al. (2019) studied the content of political WhatsApp group texts during the 2018 presidential campaign. They found that messages containing false information were more likely to spread quickly within groups, but they took longer to go beyond group boundaries. A content analysis of information shared on online platforms in India leading up to the 2019 election found that more than 25 percent of the Facebook content shared by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and a fifth of the Indian National Congress’s content was classified as misinformation (Narayanan et al., 2019). This cross-platform comparison showed that misinformation on WhatsApp is generally visual, while on Facebook, it was generally in the form of links to news sites with conspiratorial or extremist content (Narayanan et al., 2019).

Information-sharing as an economic game

Considering social networks as public goods allowed us to create an experimental paradigm. If misinformation sharing is viewed from an economic game perspective, then it could be argued that a reward mechanism that incentivizes the sharing of true content and punishes the sharing of bad content can be formulated using the volunteer’s dilemma1A game that models a situation wherein a player can either “volunteer” to make a small sacrifice for the greater benefit of the group or wait in hope of benefiting from another player’s sacrifice (Diekmann, 1985). (see e.g., Ehsanfar & Mansouri, 2018). Within this paradigm, the sharing of true information can be considered a cooperative act and can be rewarded, whereas the sharing of false information can be considered as defection and can be punished.

The present study

We investigated whether and how financial or social incentivization curbed the spread of misinformation online. Specifically, we sought to understand whether using web monetization technologies (with real money) incentivized people to share accurate information. Did (micro) financial incentives countervail other incentives and nudge individuals to be more critical media consumers and amplify high-quality content? We also investigated whether incentivizing people to share true content and disincentivizing the sharing of misinformation, either through micropayments or through social feedback, reduced the sharing of misinformation. For this purpose, we created a social media platform. Meshi, where participants were shown a total of twenty-five posts over three days that they could share, react to, or choose “read more” to get further information. Results showed that incentivization encouraged people to share more true information. However, the two incentivized groups (financial and social) did not differ in the mean number of factual posts (true and plausible) shared.

Role of incentives in sharing posts

Sharing posts when there are incentives involved can be explained by rational choice theory, which posits that choices are made through a cost-benefit analysis intended to maximize personal utility, with any form of incentive increasing the likelihood of participation (Becker, 1976; Logan et al., 2018; Zou, 2016). However, the lack of significant differences between social and financial incentives for sharing true information suggests that no particular incentive took precedence over the other. It is likely that participants were motivated solely by the presence of an incentive and a desire to earn more money or create greater social engagement.

Individuals were also equally likely to share false information regardless of the nature of the incentive. This suggests that the sharing of (mis)information is not governed only by social or monetary incentives or, conversely, that the sharing of (mis)information may be equally likely to be governed by both. It is also plausible that the kind of social incentives matter. In the current study, users gained or lost followers, whereas, in the real world, social engagement is often compounded and can take many forms (likes, reactions, shares, etc.). Similarly, the amount of money to be gained or lost can influence sharing behavior. A positive implication of this null result may be that curbing misinformation may not require substantial monetary resources. Individuals who choose to flag false content (active) or not to engage with false content (passive) can be socially incentivized for being responsible netizens.

As the social incentives in the present study were purely simulated, it is likely that participants were less concerned with whether they gained or lost “imaginary” followers. The effectiveness of social incentives can be assessed through a real-world experiment where users of a social media platform, like Facebook, can receive a visible marker, such as a star next to their profile, if they consistently share true information/factual posts. In this hypothetical experiment, with say 100 users, fact checkers can be recruited for every ten participants who would verify shared posts. Based on a predetermined threshold, users can be awarded a star denoting that they are credible sources of information on the platform. To ensure that individuals posting true information are prompted to engage with it, there can be an additional requirement of lateral reading—reading more about the information on the open internet (Wineburg et al., 2022). Further, they can supplement their post with additional sources of the information to enhance its credibility to other readers (see also McGlynn et al., 2020). This profile “star” can act as a social incentive for users to engage with and share more true information online. Additionally, a leaderboard system can be put in place that displays top users of the month who consistently share true information. Applying social incentives and criteria for sharing information online may be seen by some as curbing freedom of speech. However, individuals who share misinformation will not actively be penalized for sharing false news, nor will they be socially incentivized for sharing the same. Algorithmically, information from individuals with more “social stars” can be made more prominent in social media feeds, driving engagement with more true news than false.

As Ha et al. (2022) suggest, redesigning the online space to provide users with necessary tools to self-moderate can also be attempted. For platforms like WhatsApp and YouTube, group admins or users can be responsible for moderating content shared within groups and comment sections. With respect to handing out social incentives (like stars) to users who share true content, a trustworthy entity, such as a fact checker, can first evaluate content shared by group admins and then entrust them to provide the incentives. Indeed, with any form of incentivization involved, the question of whether social media platforms should be transparent with their users arises. In case that they employ social incentives surreptitiously, it’s likely to be business as usual, with users unaware of the underlying algorithms of the platform. On the other hand, being transparent about incentivization can lead to both beneficial outcomes (such as a better and more truthful information landscape) and unintended consequences (such as users gaming the incentives for personal gain over the common good). In our opinion, incentive mechanisms should be transparently applied to inform and engage users but could also lead to a positive ripple effect among social media platforms.

Based on the results of our study, behavior-based interventions may work just as well as financial incentives to promote the sharing of true information online. Although a recent study identified a significant effect of financial incentives on truth discernment and the subsequent sharing of factual information (Rathje et al., 2023), non-financial (and more scalable) interventions also played a role in truth discernment, albeit a smaller one. Taken together, perhaps a combined intervention may be more practical and effective (see Bak-Coleman et al., 2022), where a social incentive structure is employed as a behavior-based intervention along with other psychological interventions that have successfully demonstrated impact in curbing misinformation (see Gwiaździński et al., 2023).

Political ideology and engagement with posts

Right-leaning individuals in our study were less likely to click “read more” and more likely to share posts. The nuances in sharing behaviors among the subcategories of right-leaning individuals offer more insights into the complexities of political ideology in India. Only obedience towards hierarchical authority, and not upholding purity-based cultural norms, predicted sharing of false posts. Specific beliefs of discrimination, traditionalism, and compliance with authority are likely to be strong drivers of disseminating misinformation. Our findings are only partially consistent with past research, which suggests that conservatives are more susceptible to sharing misinformation online. However, this may be explained by samples from the United States being overrepresented in past studies, with investigations of sharing behaviors and political ideology related to political misinformation and fake news in the COVID-19 context (Calvillo et al., 2020; Garrett & Bond, 2021; Guess et al., 2019; Havey, 2020; Pennycook & Rand, 2019). Our unique findings also highlight the pitfalls of generalizing findings in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) societies to non-WEIRD ones and underscore the need to account for varying cultural influences.

Studies of misinformation sharing are scant in the Global South (countries of Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania), with this being one of the first to study web monetization in this context. The results of our study point to the eminent need for further analysis and research in the area of information-sharing on social media, especially in the Global South. As our sample was not fully representative of the Indian adult population, future work can recruit a more diverse sample, including individuals from rural and semi-urban areas, to facilitate more generalizable results. Our findings have provided multiple potential directions for future work, with one such area being understanding the influences of linguistic features of a post on decisions of sharing. Additionally, future work could also highlight the interaction between emotions and sharing behavior online. Our study also did not explore how the different themes of messages (see Table C1 in Appendix C) were shared. For example, future research could focus on whether certain socio-demographics are associated with sharing a certain type (theme) of message. Our study did not take into account the reaction time of participants (i.e., how long each participant spent evaluating the messages before engaging with them), which could potentially contribute to our understanding of sharing behavior. Additionally, given the literature on how political misinformation is widespread on social media platforms, especially in the Global South (Narayanan et al., 2019; Resende et al., 2019), researchers could look into how spreading misinformation can be a way of partisan cheerleading, if incentivization can further help our understanding of this phenomenon (e.g., Peterson & Iyengar, 2021), and how it can be curbed.

The present study can also be replicated in countries of the Global North (Adetula et al., 2022) to understand how individuals from more digitally sophisticated and literate countries respond to incentives and how that influences their sharing behavior. The start of healthier online information ecosystems may rely on exploring ways to encourage users to be more critical of the information they see, and inevitably, share.

Findings

Finding 1: Incentivization encourages people to share more true information.

The number of true posts shared in any incentivized condition was significantly higher than that of the baseline (H1),t(907) = -47.78, p < .001, d = 1.59. Significantly more true posts were shared in both incentivized conditions compared to baseline (H1a and H1b): financial, t(440) = -33.56, p < .001, d = 1.6, and social, t(466) = -33.99, p < .001, d = 1.57.

Finding 2: The type of incentive did not influence the sharing of true information.

The two incentivized groups did not differ significantly in the mean number of true (H2a), t(900.5) = 0.06, p = .95, d = 0.01, and plausible posts shared (H2b), t(903.11) = 1.34, p = .18, d = 0.09. The sharing of all factual (true and plausible) messages also did not differ across the two incentivized conditions (H2), t(902.93) = 0.79, p = .43, d = 0.05.

Finding 3: Sharing of false information was not influenced by incentives.

The type of incentive also did not influence the number of false posts shared (H3a), t(905.78) = -1.56, p = .12, d = 0.1, or the number of implausible posts shared (H3b) in the two incentivized conditions, t(905.26) = -1.75, p = .08, d = 0.11. Similarly, the sharing of all false messages (false and implausible) did not differ significantly across the two incentivized conditions (H3), t(905.51) = -1.75, p = .08, d = 0.12. This indicated that individuals were equally likely to share false information regardless of the nature of the incentive.2Based on one reviewer’s comments, we also ran exploratory analyses using proportions of true/false/plausible/implausible posts shared compared to all posts shared. Results were identical, except (a) significantly more plausible posts and significantly fewer implausible posts were shared in financial incentive condition (two-tailed); and (b) significantly more factual (true + plausible) and significantly fewer false (false + implausible) posts were shared in the financial incentive condition (one-tailed). These were exploratory analyses and not pre-registered.

Finding 4: Demographic factors and post content influence engagement with posts.

Sample descriptives and correlations for demographics, Political Ideology scales, Moral Emotions scales, posts shared and read more, and post reactions are displayed in Tables B2 and B3 in Appendix B. A few exploratory analyses were conducted to further understand how certain demographic factors and type of posts influenced engagement (see Tables D6–D9 in Appendix D). A factorial ANOVA was conducted to examine the effect of participants’ demographics (age, gender, religion, education, political ideology), reading additional information (clicking “read more”), the type of incentives (financial/social), and the type of message (true, false, plausible, implausible, wholesome) on the decision to share/not share a post (RQ2). Results indicated that this decision differed significantly based on these variables. Generally, false and implausible messages were significantly less likely to be shared as compared to true, plausible, and wholesome messages. Those who clicked on “read more” were more likely to share messages, regardless of type. The type of incentive did not influence sharing behavior.

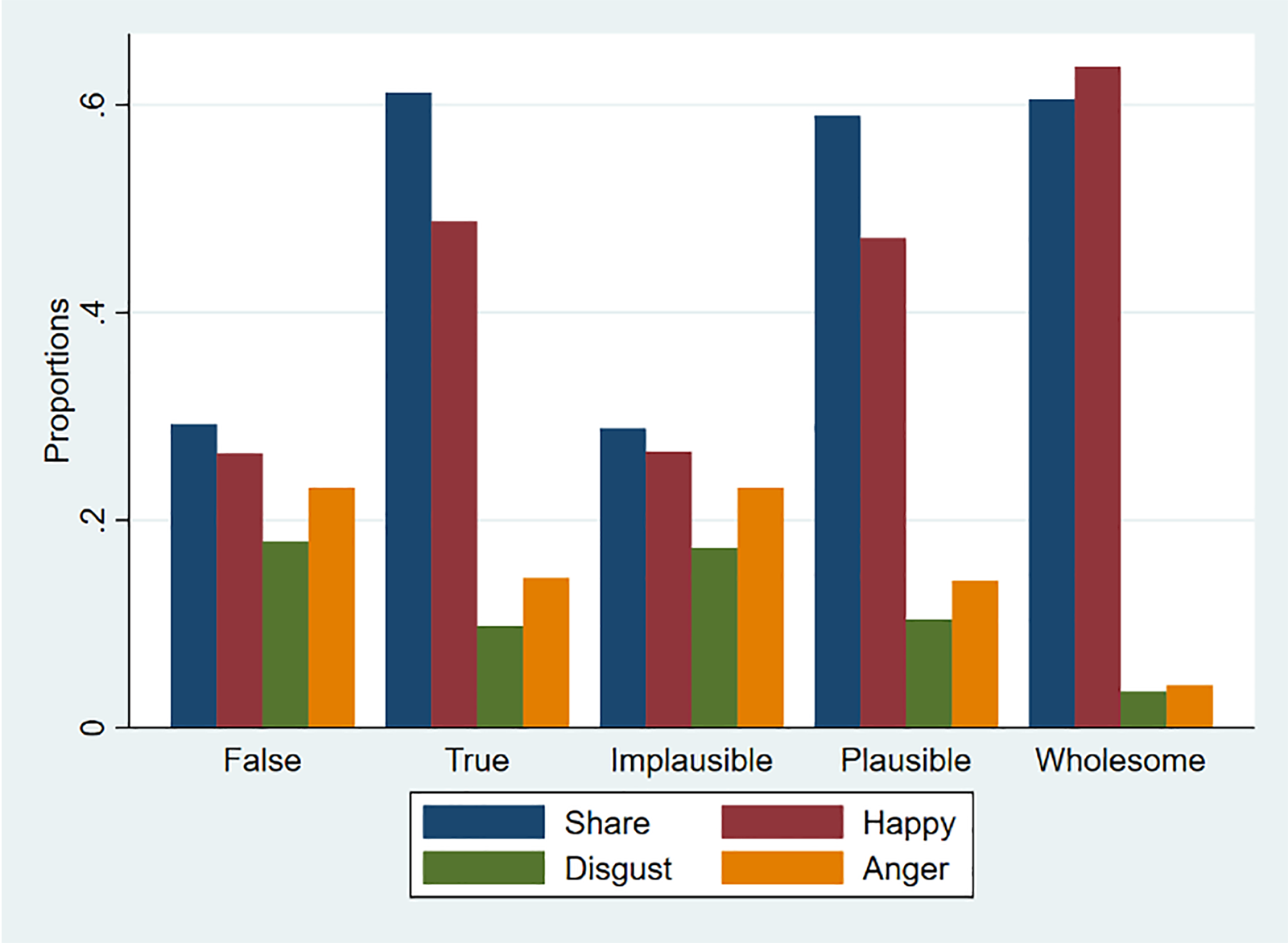

ANOVAs were also run to assess the effects of demographics and post-related behavior on happy, disgusted, and angry reactions to the messages (RQ3, Figure 1). Happy reactions were predicted by a combination of both participant demographics and post-related behavior. Factual posts—true and plausible—were more likely to elicit happy reactions than false and implausible posts; wholesome posts were more likely to elicit happy reactions than any other type of post. Those who clicked on “read more” were also more likely to give a happy reaction across conditions. Among the covariates, there was no difference between men and women when giving happy reactions to posts, and age did not influence happy reactions to posts.

Similar results were found for the social/moral emotions of disgust and anger reactions, where both demographics and post-related behavior were seen to influence such reactions to posts. Neither age nor gender influenced these reactions to posts; however, those with more right-leaning political beliefs gave more disgusted reactions. Contrary to happy reactions, disgust reactions were more likely to be elicited by false and implausible posts than true posts. However, true and plausible posts were more likely to elicit disgust reactions than wholesome posts. Reading more about the post elicited more disgust reactions; participants in the social condition gave significantly more disgust reactions than those in the financial condition. News is known to elicit emotional reactions in people (Gross & D’Ambrosio, 2004), with earlier studies indicating how such news can elicit a myriad of emotional responses (Grabe et al., 2001; Ryu, 1982). Results from the present study indicated that false and implausible posts were more likely to elicit negative reactions of anger and disgust than any other type of message.

Wholesome posts elicited more happy reactions than any other type of message. These posts included information that would generally bring joy to people, including acts of kindness, contributions made to society and the environment, and the like. Varied emotional reactions to false, true, and wholesome messages also provide content validation for the nature of posts used in the current study.

Our results also show that reading more about the post elicited more anger reactions. Participants in the financial condition gave significantly more anger reactions than those in the social condition. Older participants gave more angry reactions.

Methods

All data are openly available online, along with a pre-registration of the study. We pre-registered3See https://osf.io/k6mvu the following hypotheses:

- H1. There is a significant difference in terms of sharing true content between the baseline and the incentivized condition for all participants.

- H1a. There is a significant difference in the amount of true content shared between the baseline and the financial incentive condition.

- H1b. There is a significant difference in the amount of true content shared between the baseline and the social incentive condition.

- H2. There is a significant difference in terms of sharing true and plausible content between the incentivized conditions.

- H2a. There is a significant difference in terms of sharing true content between participants who earn social incentives versus those who earn financial incentives.

- H2b. There is a significant difference in terms of sharing plausible content between participants who earn social incentives versus those who earn financial incentives.

- H3. There is a significant difference in terms of sharing false and implausible content between the incentivized conditions.

- H3a. There is a significant difference in terms of sharing false content between participants who earn social incentives versus those who earn financial incentives.

- H3b. There is a significant difference in terms of sharing implausible content between participants who earn social incentives versus those who earn financial incentives.

- H4. Those in the social incentive condition are more likely to share wholesome content compared to those in the financial incentive condition.

The study link for the screening survey was posted on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram. The link directed the participants to a Qualtrics form where they had to respond to a few demographic questions, a short questionnaire assessing their political ideology, and a bot test. Those who fulfilled the inclusion criteria (being at least 18 years of age, an Indian citizen, passing the attention checks, and completing all three days of the experiment) and consented to participate were invited via email to participate in the experiment.

Participants

A total of 2,464 participants filled out a screening survey (described subsequently), out of which the data of 908 participants (women = 336, men = 552, other = 20; Mage = 28.8, SD = 65.61, age range:18–69 years, Hindus = 712, Muslims = 54, Christians = 28, Atheists = 51, Other religions = 63) were retained.4Of the 2,464 that filled out the survey, 1,557 individuals fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were invited to participate in the study. Of the 1,557 individuals, there were participants who dropped out at different stages of the experiment, and only 940 individuals completed all three days of the experiment. Data from these participants were further cleaned based on other inclusion criteria (passing the attention checks), and finally, valid data from 908 participants were retained. Invalid responses were discarded based on nationality (not Indian), age (below 18 years), self-reported honesty (< 7 on a 10-point scale), not passing at least one of the two attention checks, not completing all three days of the study, and if they had duplicate responses. About 50% of the sample were employed, 26% were students, 11% were self-employed, and less than 5% were either unemployed or retired. Of the 908 participants, 441 were part of the financial condition, and 467 were part of the social condition (Table B1 in Appendix B).

Procedure

The experimental task involved a social media platform, Meshi, created for the study where participants were given unique login IDs to sign in, as in any social media platform (Appendix A). The experiment was done over three days for each participant to reduce fatigue. Participants were shown a total of twenty-five posts: five posts on the first day (baseline) and ten each on the following two days. Each message shown belonged to one of the five types: true, false, plausible, implausible, and wholesome.

The posts under the “plausible” category were phrased to indicate the probability or likelihood of a certain piece of factual information being true (e.g., “There is a 90% chance that India will not experience a fourth wave of the coronavirus”). The “implausible” category posts were also created with the probability/likelihood phrasing (e.g., “There is a high chance that India’s third COVID-19 wave was not the last one”); however, the posts here were not factual. The posts under the true (e.g., “Scientists believe that new COVID-19 infections are not a major concern anymore”) and false categories (e.g., “There will not be any new variants of the coronavirus after omicron”) contained the same information as those in the plausible and implausible categories but without the probability or likelihood phrasing. Wholesome posts were those that were likely to elicit joy; for example, “Dog that knows 40 commands gets a job at a children’s hospital in the US.” Details about content creation and the conditions are included in Appendix B.

Participants could choose to (a) share the post, and/or (b) react to it using one of the three emojis displayed depicting the emotions of anger, happiness, and disgust, and/or (c) press “read more” to get further information on the message displayed. The participants were not shown engagement metrics against the messages displayed (i.e., the amount of engagement each message received from other Meshi users) as this was not an interactive social media platform. Further, participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions—financial or social incentives.

In the financial incentive condition, participants were informed that they have to read the message thoroughly and use their judgment to determine which content is true or false, and which would spread joy (wholesome). Further, on the second and third days of the study, participants were informed that they will be rewarded for sharing true/plausible content by receiving ₹10 in their Meshi wallet and penalized for sharing false/implausible content by deduction of ₹4 from their wallet. The instructions for the social incentive condition were the same; however, with respect to rewards, on the second and third days of the study, participants were informed that they will be rewarded for sharing true content by getting 100 followers for each true content shared and will be penalized for sharing false content by deduction of 40 followers. Sharing wholesome posts did not entail receiving any incentives or disincentives in both conditions. All participants received initial endowments of ₹ 40 and 400 followers at the start of the experiment.

At the end of Day 3, participants responded to a Qualtrics form with a few post-task questions measuring moral emotions associated with the experimental task, their engagement (emotional and attention) with that task, understanding of the incentives associated with sharing, and open-ended questions about motivations for sharing/not sharing the posts (Appendix C).

Topics

- Asia

- / Emotion

- / Psychology

- / Social Media

Bibliography

Adetula, A., Forscher, P. S., Basnight-Brown, D., Azouaghe, S., & IJzerman, H. (2022). Psychology should generalize from — not just to — Africa. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(7), 370–371. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00070-y

Bak-Coleman, J. B., Kennedy, I. M., Wack, M., Beers, A., Schafer, J. A., Spiro, E. S., Starbird, K., & West, J. D. (2022). Combining interventions to reduce the spread of viral misinformation. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(10), 1372–1380. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01388-6

Bastick, Z. (2021). Would you notice if fake news changed your behavior? An experiment on the unconscious effects of disinformation. Computers in Human Behavior, 116, 106633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106633

Becker, G. S. (1976). The economic approach to human behavior. University of Chicago Press.

Calvillo, D. P., Ross, B. J., Garcia, R. J. B., Smelter, T. J., & Rutchick, A. M. (2020). Political ideology predicts perceptions of the threat of COVID-19 (and susceptibility to fake news about it). Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(8), 1119–1128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620940539

Diekmann, A. (1985). Volunteer’s dilemma. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 29(4), 605–610. https://www.jstor.org/stable/174243

Ehsanfar, A., & Mansouri, M. (2017). Incentivizing the dissemination of truth versus fake news in social networks. In12th System of Systems Engineering Conference (SoSE), (pp. 1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/SYSOSE.2017.7994981

Flaxman, S., Goel, S., & Rao, J. M. (2016). Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 298–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw006

Friggeri, A., Adamic, L. A., Eckles, D., & Cheng, J. (2014). Rumor cascades. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 8(1), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v8i1.14559

Garrett, R. K., & Bond, R. M. (2021). Conservatives’ susceptibility to political misperceptions. Science Advances, 7(23), eabf1234. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abf1234

Grabe, M. E., Zhou, S., & Barnett, B. (2001). Explicating sensationalism in television news: Content and the bells and whistles of form. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 45(4), 635–655. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4504_6

Gross, K., & D’ambrosio, L. (2004). Framing emotional response. Political Psychology, 25(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00354.x

Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances, 5(1), eaau4586. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4586

Gwiaździński, P., Gundersen, A. S., Piksa, M., Krysińska, I., Kunst, J. R., Noworyta, K., Olejniuk, A., Morzy, M., Rygula, R., Wójtowicz, T., & Piasecki, J. (2023). Psychological interventions countering misinformation in social media: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.974782

Ha, L., Graham, T., & Gray, J. E. (2022). Where conspiracy theories flourish: A study of YouTube comments and Bill Gates conspiracy theories. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 3(5). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-107

Havey, N. F. (2020). Partisan public health: how does political ideology influence support for COVID-19 related misinformation? Journal of Computational Social Science, 3(2), 319–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-020-00089-2

Hudson, S., Roth, M. S., Madden, T. J., & Hudson, R. (2015). The effects of social media on emotions, brand relationship quality, and word of mouth: An empirical study of music festival attendees. Tourism Management, 47, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.001

Logan, K., Bright, L. F., Grau, S. L., 2018. “Unfriend me, please!”: Social media fatigue and the theory of rational choice. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 26(4), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2018.1488219

Lin, X., & Wang, X. (2020). Examining gender differences in people’s information-sharing decisions on social networking sites. International Journal of Information Management, 50, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.05.004

McGlynn, J., Baryshevtsev, M., & Dayton, Z. A. (2020). Misinformation more likely to use non-specific authority references: Twitter analysis of two COVID-19 myths. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-37

Mitra, A. (2020, June). Why do WhatsApp users end up spreading misinformation in India? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/anandamitra/2020/06/29/why-do-whatsapp-users-end-up-spreading-misinformation-in-india/

Narayanan, V., Kollanyi, B., Hajela, R., Barthwal, A., Marchal, N., & Howard, P. N. (2019, May 13). News and information over Facebook and WhatsApp during the Indian election campaign. Programme on Democracy and Technology. https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/research/posts/news-and-information-over-facebook-and-whatsapp-during-the-indian-election-campaign/

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2019). Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition, 188, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.011

Pennycook, G., Cannon, T. D., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(12), 1865–1880. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000465

Peterson, E. J., & Iyengar, S. (2021). Partisan gaps in political information and information‐seeking behavior: Motivated reasoning or cheerleading? American Journal of Political Science, 65(1), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12535

Rathje, S., Roozenbeek, J., Pretus, C., & Van Der Linden, S. (2023). Accuracy and social motivations shape judgements of (mis)information. Nature Human Behaviour, 7, 892–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01540-w

Resende, G. G., Melo, P., Sousa, H., Messias, J., Vasconcelos, M., Almeida, J. M., & Benevenuto, F. (2019). (Mis)information dissemination in WhatsApp: Gathering, analyzing and countermeasures. In L. Liu & R. White (Eds.), Proceedings of WWW ’19: The Web Conference (pp. 818–828). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3308558.3313688

Ryu, J.S. (1982). Public affairs and sensationalism in local TV news programs. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 59, 137–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769908205900111

Safieddine, F., Dordevic, M., & Pourghomi, P. (2017). Spread of misinformation online: Simulation impact of social media newsgroups. In Proceedings of 2017 Computing Conference (pp. 899–906). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/SAI.2017.8252201

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Wang, Y., Dai, Y., Li, H., & Song, L. (2021). Social media and attitude change: Information booming promote or resist persuasion? Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.596071

Wineburg, S., Breakstone, J., McGrew, S., Smith, M. A., & Ortega, T. (2022). Lateral reading on the open Internet: A district-wide field study in high school government classes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(5), 893–909. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000740

Zou, Y. (2016). Buying love through social media: How different types of incentives impact consumers’ online sharing behavior [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Old Dominion University. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=marketing_etds

Funding

This project was funded by the Grant for the Web.

Competing Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics committee at Monk Prayogshala in March 2022 (#086-022). Gender differences were investigated in the present study as these differences were noted in a prior study (Lin & Wang, 2020) in terms of information sharing on social media. Gender categories were determined based on inclusive guidelines (Cameron & Stinson, 2019).

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VPDRF3