Peer Reviewed

Seeing lies and laying blame: Partisanship and U.S. public perceptions about disinformation

Article Metrics

1

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Using data from a nationally representative survey of 2,036 U.S. adults, we analyze partisan perceptions of the risk disinformation poses to the U.S. government and society, as well as the actors viewed as responsible for and harmed by disinformation. Our findings indicate relatively high concern about disinformation across a variety of societal issues, with broad bipartisan agreement that disinformation poses significant risks and causes harms to several groups. However, agreement ends there. Republicans and Democrats fundamentally disagree on who is responsible. We discuss the implications of this disagreement for understanding disinformation as a policy problem and the implications for policy solutions.

Research Questions

- RQ1: How do members of the U.S. public perceive the various risks of disinformation to society? Do these perceptions cut across partisan divides?

- RQ2: Who do members of the public believe is responsible for and is harmed by disinformation? Do these beliefs cut across partisan divides?

Essay Summary

- We use data from a nationally representative survey of 2,036 respondents to measure public perceptions and beliefs about disinformation.

- Most respondents, including both Democrats and Republicans, agree that disinformation poses substantial risks to national security, public health, the economy, international relations, and governmental stability.

- There was much less agreement on who is responsible for and who is harmed by disinformation.

- These findings indicate that despite strong agreement about the problem, it will prove challenging to create broadly acceptable policy solutions because divergent beliefs about the sources and consequences of disinformation imply very different policy directions.

Implications

While there is a broad literature on the threat disinformation poses to individuals, governance, and society, little has been written about what the public believes to be the nature of the harm resulting from disinformation (Knuutila et al., 2022; Rich, 2022; Rodríguez-Virgili et al., 2020). For example, though Knuutila et al. (2022) have provided a very useful model of misinformation risk perceptions across 142 countries, their work chiefly addresses broad concerns about misinformation and the socioeconomic variables that shape those concerns. There has been little systematic analysis of the specific institutions, groups, or norms that are perceived to be at risk and whom the public blames for the disinformation problem. Using survey results from a 2021 survey, we explore public perceptions of the risk disinformation poses, who is harmed, and who is responsible. Our results indicate that despite agreement that disinformation poses a risk, there are fundamental disagreements about who is to blame and who is harmed. We argue that these perceptions directly impact policymaking by shaping policy problem definition, policy scope, and the ability to develop and implement policies.

According to the Global Disinformation Lab (GDL), policymakers face five challenges in developing policies to mitigate disinformation. These challenges are definitions, scope, evaluation, free expression, and political will (Hernandez & Poursoltan, 2023). In order to address several of these challenges, policymakers must first understand how disinformation is perceived as a problem and who is perceived as responsible for and harmed by disinformation. Problem definition and actor attribution are key to all challenges; however, these aspects are crucial to definitions, scope, and political will.

First, the way problems are defined, and actors are perceived as blamed or harmed by that problem lay the foundation for policymaking through the development of a policy narrative (Jones & McBeth, 2010; Stone, 1989; Stone, 2002). These narratives impact the types of policies that can be developed and implemented. In extreme cases, such as areas subject to polarization, competing policy narratives can inhibit any policymaking whatsoever. There is evidence that one of the significant roadblocks to crafting counter-disinformation policy is the lack of an agreed-upon legal definition of disinformation (Ó Fathaigh et al., 2021). While there can be negative implications to legally defining disinformation, even an informal agreement on the problem, such as an agreement that disinformation is harmful, is crucial to policy development. This agreement becomes increasingly unlikely as polarization impacts what people believe is disinformation and who they believe is responsible. Definitions directly relate to the challenge of policy scope. Scope relates to the types of disinformation, actors responsible and harmed, and where the disinformation is spread (e.g., social media). For example, our research indicates bipartisan agreement on foreign actor responsibility and disagreement on domestic actors, indicating that potential policies may be limited to foreign disinformation. Last, regarding political will, the GDL report states that “polarization and gridlock are uniquely problematic for addressing disinformation, because disinformation itself is believed to feed into political dysfunction” (Global Disinformation Lab, 2023, p. 5). Polarization in the policymaking process can manifest in different ways, from diverging policy definitions to efforts by policymakers of one party to develop counter-disinformation policies, which policymakers of the opposite party accuse of unfairly targeting or censoring that party. For example, the Biden Administration’s recent attempt to develop the Department of Homeland Security’s Disinformation Governance Board disbanded after Republican accusations that it would act as a censor and unfairly target conservatives (Merchant & Seitz, 2022). This example underscores the importance of finding bipartisan agreement in counter-disinformation policy development.

While the GDL report indicates that counter-disinformation policy faces unique challenges with polarization, it is important to put our results on polarization and bipartisan agreement in context. COVID-19, like disinformation, has been an area where there has been little bipartisan agreement. However, in a 2021 poll, when asked if COVID-19 posed a threat to the economy, Democrats and Republicans agreed (Schaeffer, 2021). This example is similar to our risk perception results in that respondents were asked about a broad threat. Thus, we can expect close bipartisan agreement when issues are framed as a broad threat to society rather than a specific threat, with some exceptions. We see more polarization related to specific issues and actors, particularly those highly salient to a respondent’s party. For example, perceptions of the risks of election fraud and the perceived winner of a specific election are highly partisan. For example, regarding the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Trump voters view fraud as more likely than Democrats and are less likely to view Joe Biden as legitimately elected (Pennycook & Rand, 2021).

Our research seeks to understand the extent to which people view disinformation as a risk to society and government and to probe views of who the villains and victims are of the disinformation problem. While our data is from 2021, we argue that this data is still relevant for understanding problem definition because perceived villains and victims are likely the same today and because partisan divide on problem definition has continued to inhibit policymakers’ ability to address disinformation. Furthermore, even as the types of issues impacted by disinformation change, perceptions are likely to look similar today as we still live in a highly partisan environment. It is important to understand where there is agreement and where there is not to determine how to formulate policies to address disinformation. Where disagreement looms large, policy formulation and implementation may prove to be difficult. Our findings demonstrate that U.S. residents generally agree that disinformation is a significant problem, which is consistent with extant literature (Rich, 2022), and, for the most part, that foreign governments and actors are seen as responsible for spreading disinformation. This agreement matters because it indicates that policy addressing foreign disinformation could see bipartisan agreement. Although, as the Homeland Security Governance Board example demonstrates, addressing foreign disinformation can still be highly polarizing. However, our results also demonstrate that the narratives surrounding disinformation are complex and entangled with partisan polarization, particularly regarding the attribution of blame and harm to different types of domestic actors. So, while overall agreement on disinformation as a problem provides modest grounds for optimism, the more detailed and divided narratives surrounding disinformation highlight the substantial challenges that public opinion poses for policymakers tasked with creating and implementing policy measures. Solutions should, therefore, focus on disinformation’s overall harm and risks rather than on specific actors.

Findings

Finding 1: The U.S. public agrees that disinformation poses a risk.

Broad agreement on the definition of a policy problem is an important first step toward developing solutions. We, therefore, examine the extent to which the public believes disinformation is a problem and whether there is bipartisan agreement on disinformation as a risk. Our analysis provides evidence for the extent to which disinformation is broadly recognized as a significant problem among the U.S. public and the degree to which disinformation beliefs are driven by partisan alignment.

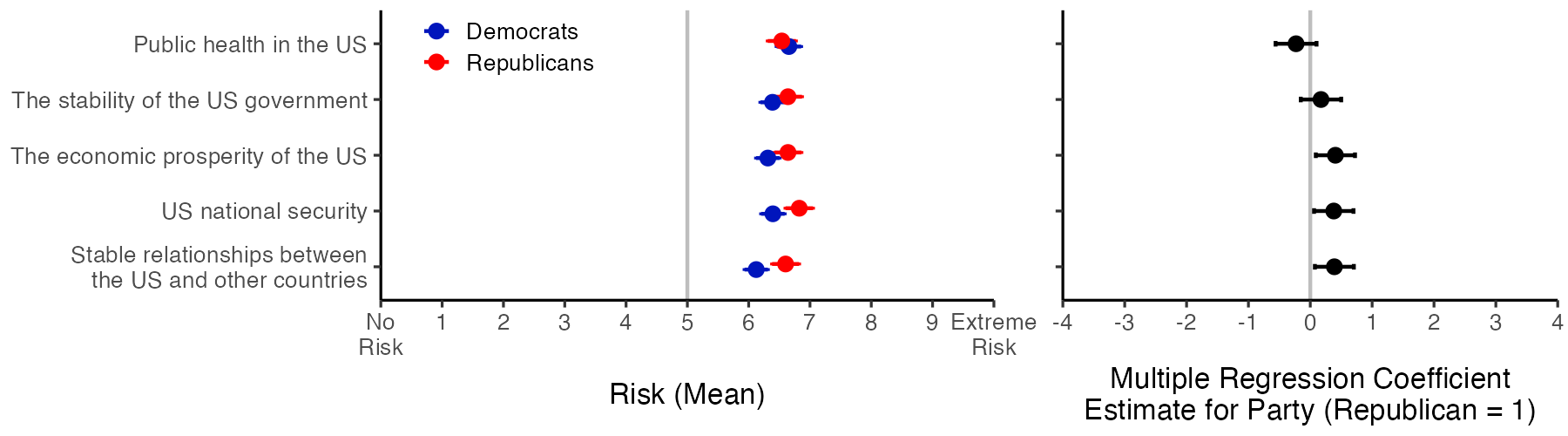

We first asked respondents to rate the risk posed by disinformation on a scale that ranged from 0 (no risk) to 10 (extreme risk) in several areas: public health, national security, economic prosperity, relations between the United States and other countries, and U.S. government stability. Across all categories, respondents rate the risk of disinformation above midscale, indicating that disinformation is widely seen to pose a substantial risk. When controlling for demographics, such as race, education, income, age, and gender, there is little statistical or substantive difference between Republicans and Democrats. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to report higher risk to national security, international relations, and economic prosperity. However, the difference is substantively small, thus indicating bipartisan agreement that disinformation poses a risk.

Finding 2: Democrats and Republicans agree that different actors are harmed but are polarized on the topic of responsibility for disinformation production.

While our survey presents evidence of bipartisan agreement on disinformation as a problem, to what extent is there agreement on who the villains and victims are? Agreement on who is responsible for the production and spread of disinformation and who is harmed by disinformation is crucial for developing solutions. However, as is the case for many salient and divisive policy problems, party alignment, policy core beliefs, information sources, emotions, and elite cues cause a divergence in beliefs about who is responsible and who is harmed by disinformation campaigns. Groups (such as political parties) are likely to portray themselves as a hero or a victim while villainizing an opposing group (Jones & McBeth, 2020). Thus, our results that indicate polarization in these areas, particularly relating to blame, are consistent with expectations. Our results indicate some bipartisan agreement on who is harmed by disinformation. However, that bipartisan agreement breaks down on attributions of responsibility, with the notable exception of foreign governments.

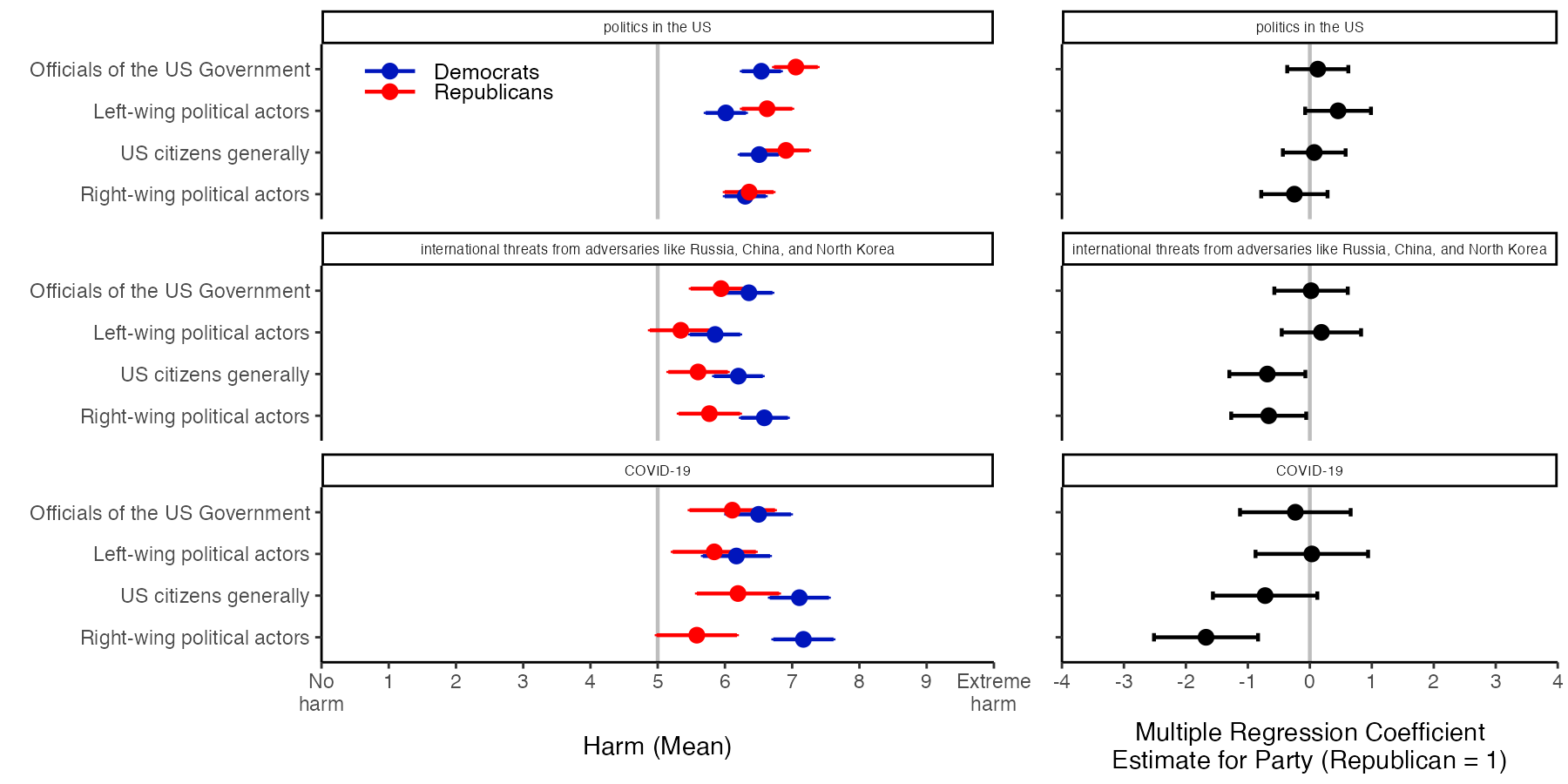

There is slightly more polarization regarding who respondents believe is harmed by disinformation than overall risk perceptions. However, as demonstrated in Figure 2, Democrats and Republicans do tend to agree that disinformation harms all groups. On a scale ranging from 0 (no harm) to 10 (extreme harm), the average harm to all groups ranges between 5.3 and 7.2. Democrats and Republicans most agree on the harm caused to right-wing political actors by disinformation on U.S. politics. Figure 2 presents the means and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression results for the differences between Republicans and Democrats when controlling for demographic variables. The results indicate the greatest area of polarization is on the harm that COVID-19 causes to right-wing political actors, with Democrats rating the amount of harm higher than Republicans. Democrats and Republicans are in closer agreement that disinformation about international threats and U.S. politics causes harm to all actors. We found it surprising that Democrats rate the risk of COVID-19 disinformation to right-wing actors higher than Republicans, as groups are more likely to perceive themselves as victims. It could be, as Figure 3 demonstrates, that they perceive Republicans to be responsible for spreading disinformation and that, because of this, they believe that Republican actors may be more likely to believe it and act upon it, or because Democrats perceive that right-wing political actors’ reputations are harmed (e.g., people lose trust in these actors and subsequently decide not to vote for them).

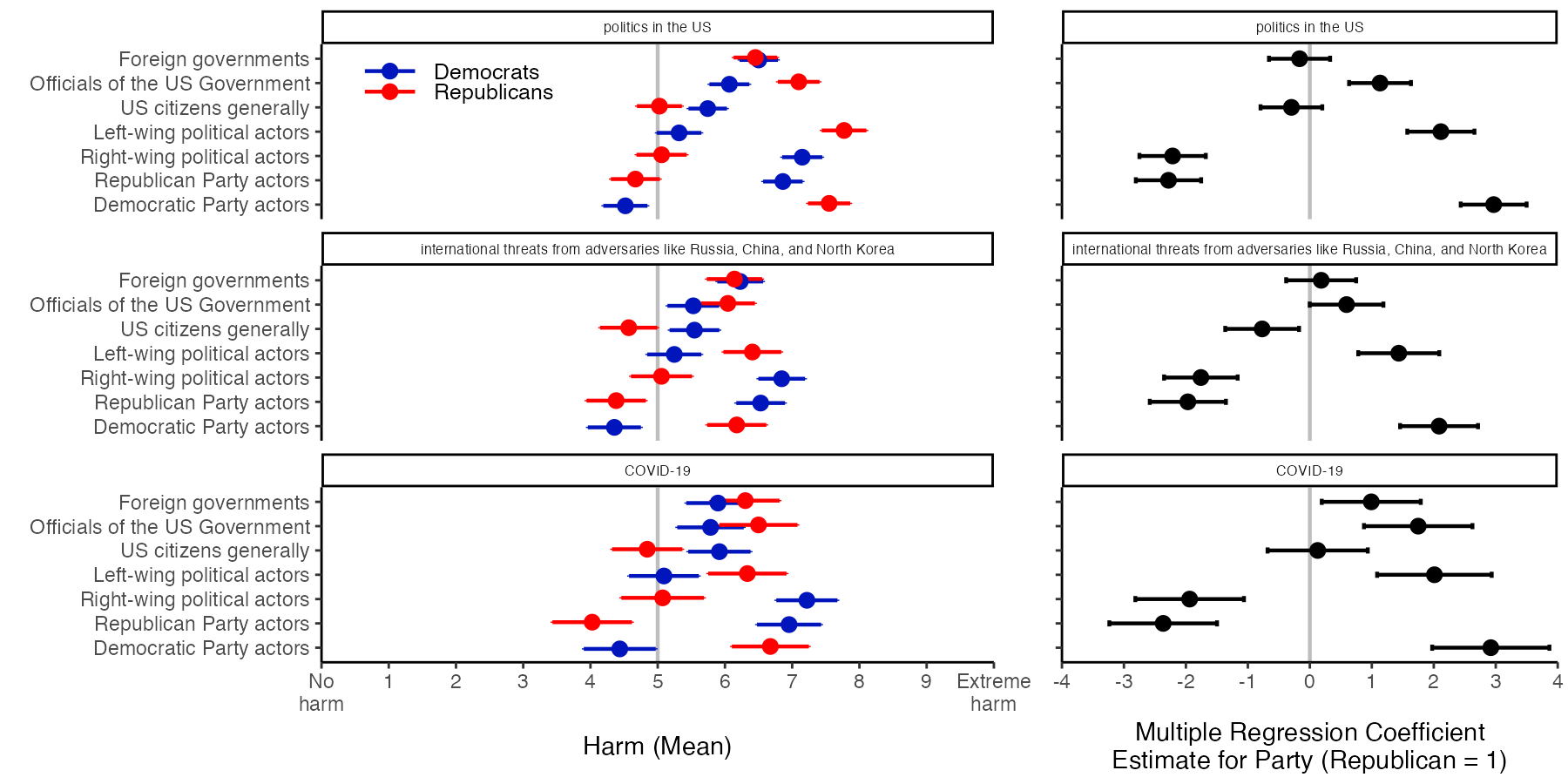

Bipartisan agreement breaks down when respondents are asked to rate actors’ responsibility for the production of disinformation, with the exception of foreign governments. Respondents were asked to rate actors’ responsibility on ascale from 0 (not at all responsible) to 10 (fully responsible). Mean responsibility ratings ranged from 4 to 7.6. The regression coefficients in Figure 3 indicate that, when controlling for demographic characteristics and regardless of information type, Democrats tend to place responsibility on right-wing and Republican actors, whereas Republicans place responsibility on left-wing and Democratic actors. This is consistent with the policy literature that indicates coalitions may villainize an opposing group or actor (Jones & McBeth, 2020). Thus, solutions that focus on the responsibility of domestic actors could prove to be problematic and viewed as a particular party trying to limit free speech of the other party. It would be challenging for policymakers from both parties to agree upon these solutions, much less implement them.

Despite these highly partisan results, there is one actor that Republicans and Democrats tend to agree is responsible for the spread of disinformation—foreign governments. This agreement indicates the potential for forming policy solutions targeting foreign disinformation. However, it is important to keep in mind that this agreement could disappear when talking about specific foreign actors, such as Vladimir Putin, because perceptions of foreign actors, in general, are polarized. Therefore, we might expect Republicans to place less blame on Putin than Democrats.

By examining who the public believes are the villains and victims of the disinformation problem, we can begin to better understand the policy narratives that might contribute to effective solutions. Solutions focusing on domestic actors as the perpetrators are much less likely to gain traction among policymakers and the public than solutions focusing on the harm disinformation causes to everyone, disinformation as a broad problem, and the role foreign actors play in spreading disinformation. This is not to say these types of solutions would not encounter partisan pushback. Focusing on harm and the challenges caused by disinformation emphasizes that we are all susceptible to believing and being harmed by disinformation rather than pointing fingers and assigning blame, which is likely to exacerbate polarization and stall policy progress.

Methods

The data for this study consists of 2,036 responses to a nationally representative online survey of U.S. adults fielded by the University of Oklahoma Institute for Public Policy Research & Analysis in December 2021. This survey is one in a series conducted annually. However, the 2021 implementation is the first year in which the disinformation question set was included. Therefore, this dataset provides a snapshot of risk perceptions in 2021. The public’s concerns about certain types of disinformation and the actors they believe are harmed by or responsible for disinformation are likely to change over time. However, the 2021 data are still relevant to policy topics and policymaking related to disinformation today, as these perceptions have impacted policymaking in the last few years and are likely similar today.

The questions asked participants to rate the risk that disinformation campaigns pose to five areas of government and society: U.S. national security, public health in the United States, the stability of the U.S. government, economic prosperity of the United States, and stable relationships between the United States and other countries. Then,participants were asked to rate actor responsibility, harm, and benefit. When rating actors, respondents were randomly assigned into three disinformation categories: U.S. politics, international threats from adversaries like Russia, China, and North Korea, and COVID-19. These disinformation categories were selected to represent the broad array of disinformation and the salient issues impacted by disinformation at the time of the survey. We selected a range of actors, primarily describing groups in broad terms, as this was an initial exploration of risk perceptions and actor attribution. In open-ended responses, we saw, for example, participants identifying a range of foreign actors. Future research will focus on more specific actors. We chose to use QAnon and Antifa as examples of right- and left-wing groups because they are prominently cited on social media and sometimes by policymakers and media, as spreaders of disinformation. In other words, despite the fact that they lack formal organization, there are perceptions that these actors are responsible for disseminating disinformation and acting along ideological and party lines. Respondents were allowed to skip questions but were not given a “don’t know” option.

For this article, we examined the following questions: What are the public’s perceptions of the risks of disinformation to government and society? And, who does the public believe is responsible for, benefits from, and is harmed by disinformation? We then looked at the patterns of partisan differences in risk perceptions and the degree to which responsibility, benefit, and harm are assigned to evaluate the degree to which partisanship and partisan signaling play a role in belief and sharing behaviors (Osmundsen et al., 2021; Pretus, 2023; Sinderman et al., 2020). While our survey question on party affiliation included response options for Independents and Others, we excluded these groups from our analysis to demonstrate differences between the two major parties. Our results indicate that party affiliation drives perceptions of disinformation, posing a challenge for finding agreement on solutions to the disinformation problem. Given our focus, a descriptive approach was selected to provide a basis for understanding patterns of risk perceptions.

Topics

Bibliography

Gawronski, B. (2021). Partisan bias in the identification of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(9), 723–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.05.001

Hernandez, A., & Pursoltan, C. (Eds.) (2023). US disinformation policy in perspective: Comparative global disinformation challenges. Global Disinformation Lab. https://gdil.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/gdpd_whitepaper_v2.pdf

Jones, M. D., & McBeth, M. K. (2010). A narrative policy framework: Clear enough to be wrong? Policy Studies Journal, 38(2), 329–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00364.x

Jones, M. D., & McBeth, M. K. (2020). Narrative in the time of trump: Is the narrative policy framework good enough to be relevant? Administrative Theory & Praxis, 42(2), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2020.1750211

Knuutila, A., Neudert, L.-M., & Howard, P. N. (2022). Who is afraid of fake news? Modeling risk perceptions of misinformation in 142 countries. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-97

Merchant, N., & Seitz, A. (2022, May 18). New “disinformation” board paused amid free speech questions. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/government-and-politics-national-security-83c67505703c02b0de154b21abd5c569

Myers, S. L., & Frenkel, S. (2023, June 19). G.O.P. targets researchers who study disinformation ahead of 2024 election. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/19/technology/gop-disinformation-researchers-2024-election.html

Ó Fathaigh, R., Helberger, N., & Appelman, N. (2021). The perils of legally defining disinformation. Internet Policy Review, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2021.4.1584

Osmundsen, M., Bor, A., Vahlstrup, P. B., Bechmann, A., & Petersen, M. B. (2021). Partisan polarization is the primary psychological motivation behind political fake news sharing on Twitter. American Political Science Review, 115(3), 999–1015. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000290

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Examining false beliefs about voter fraud in the wake of the 2020 Presidential Election. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-51

Pretus, C., Servin-Barthet, C., Harris, E. A., Brady, W. J., Vilarroya, O., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2023). The role of political devotion in sharing partisan misinformation and resistance to fact-checking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152(11), 3116–3134. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001436

Rich, T. S. (2022). South Korean perceptions of misinformation on social media: The limits of a consensus? Journal of Asian and African Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096221137662

Rodríguez-Virgili, J., Serrano-Puche, J., & Fernández, C. B. (2021). Digital disinformation and preventive actions: Perceptions of users from Argentina, Chile, and Spain. Media and Communication, 9(1), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3521

Schaffer, K. (2021, March 24). Despite wide partisan gaps in views of many aspects of the pandemic, some common ground exists. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/03/24/despite-wide-partisan-gaps-in-views-of-many-aspects-of-the-pandemic-some-common-ground-exists/

Sindermann, C., Cooper, A., & Montag, C. (2020). A short review on susceptibility to falling for fake political news. Current Opinion in Psychology, 36, 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.03.014

Stone, D. A. (1989). Causal stories and the formation of policy agendas. Political Science Quarterly, 104(2), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/2151585

Stone, D. (2002). Policy paradox: The art of political decision making. W. W. Norton & Company.

Funding

Funding for data collection was provided by the Office of the Vice President for Research and Partnerships at the University of Oklahoma.

Competing Interests

None.

Ethics

This research involved huma subjects that provided informed consent. The research protocol was approved by the University of Oklahoma Norman Campus Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 6168; IRB approval data: 12/18/2023).

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PRP4WX