Peer Reviewed

Legislator criticism of a candidate’s conspiracy beliefs reduces support for the conspiracy but not the candidate: Evidence from Marjorie Taylor Greene and QAnon

Article Metrics

3

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

In November 2020, Georgia Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene became the first open supporter of QAnon to be elected to the United States Congress. Despite criticism from Democrats, Republicans, and the media for her belief in this dangerous conspiracy theory, Greene remains a prominent national figure and a member of Congress. In a large survey experiment examining the effects of criticisms of Greene by different sources, we found that criticism of Greene from a Republican or a Democratic official reduced positive feelings toward QAnon but not Greene herself. However, unsourced criticisms and criticisms from media figures failed to measurably affect feelings toward either Greene or QAnon. Our results suggest that public officials have a unique responsibility to criticize misinformation, but they also highlight the difficulty in shifting attitudes toward politicians who embrace and spread falsehoods.

Research Questions

- Does exposure to criticism of Marjorie Taylor Greene that discusses her links to QAnon make people feel more negatively toward her and/or QAnon?

- Does exposure to Republican criticism of Marjorie Taylor Greene make Republicans feel more negatively toward her than criticism from other sources?

- Does exposure to criticism of Marjorie Taylor Greene from Democrats or the media make Republicans feel more positively toward her?

Essay Summary

- In an experiment conducted via YouGov (March 9–23, 2021; N = 5,575), we tested the effects of exposure to criticism of Marjorie Taylor Greene’s support for conspiracy theories such as QAnon on people’s feelings toward both her and QAnon.

- We find that criticisms of Greene from both Democrat and Republican officials made people view QAnon more negatively, but unsourced criticisms and those from media figures had no measurable effect. None of the criticisms made respondents feel more negatively toward Greene herself.

- These findings suggest that many current criticisms of figures like Greene may be largely ineffective at reducing her popularity. However, public officials who speak out may still be able to help discredit the conspiracy theories they target.

Implications

The QAnon conspiracy theory holds that Donald Trump is secretly fighting an international cabal of Satan- worshipping pedophiles (Aliapoulios et al., 2021). Surveys suggest that as many as four in five Republicans do not fully reject the QAnon conspiracy theory (Russonello, 2021) (though see Hill and Roberts, n.d., for how standard survey measures may inflate estimates of conspiracy belief). Researchers have documented cases of QAnon motivating people to commit violent criminal acts (Amarasingam & Argentino, 2020). Contrary to many claims from news media and other scholars, however, QAnon is unpopular among most of the American public and has not significantly increased in popularity over time (Enders et al., 2022).1For example, Garry et al. (2021) claim that QAnon has grown at an “unprecedented speed.” Though our survey does not measure the popularity of QAnon over time, our pretreatment measures of feelings toward QAnon confirm that QAnon is indeed generally unpopular: respondents in our sample rated QAnon at 12.1 on a 101-point feeling thermometer (Democrats rated QAnon 6.7, while Republicans rated QAnon 24.3).

In November 2020, Georgia Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene became the first open supporter of QAnon to be elected to the United States Congress (Rosenberg et al., 2020). Greene has also falsely claimed that Barack Obama is secretly Muslim, that a plane did not crash into the Pentagon on 9/11, and that the 2021 California wildfires were caused by lasers from space (Steck & Kaczynski, 2021). However, despite frequent criticism of Greene from Democrats, Republicans, and the media, 27% of GOP voters still view Greene favorably and only 18% view her unfavorably (Yokley, 2021). Republicans who view Greene favorably may not have been exposed to criticisms of Greene or may not care about these criticisms. Alternatively, media or Democratic criticism of Greene might fuel favorable views of Greene among Republicans. Understanding how to criticize conspiracy theorists in a way that diminishes their popularity and the popularity of the conspiracy theories they promote is essential for researchers and policymakers trying to combat misinformation.

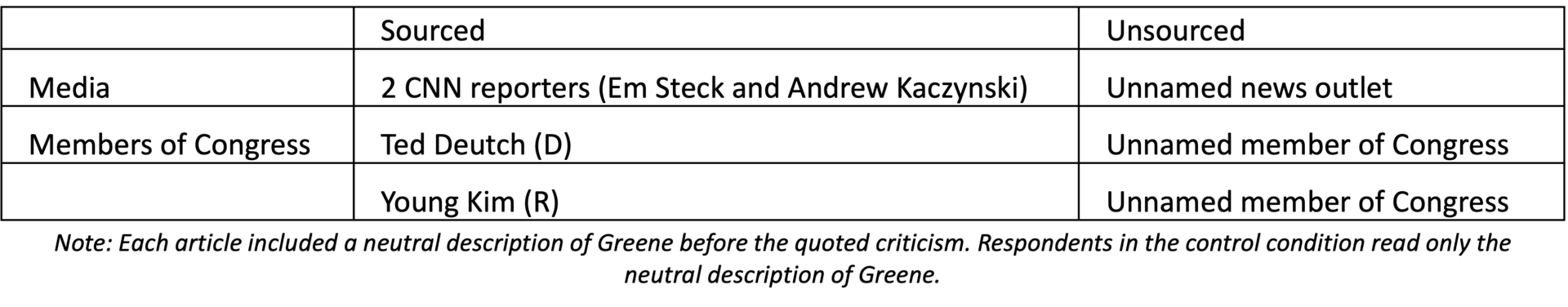

This study explores how criticisms of Greene that discuss her links to QAnon affect respondents’ feelings toward Greene and toward QAnon. Given prior research from Vraga and Bode (2018) suggesting that the source of a correction can influence its efficacy, we compared a baseline condition with no criticism to criticism conditions citing various sources: two CNN reporters (Em Steck and Andrew Kaczynski), an unnamed news outlet, a Democratic member of Congress (Ted Deutch), a Republican member of Congress (Young Kim), or the Deutch or Kim criticisms attributed to an unnamed member of Congress (with no mention of partisanship). The three unsourced criticism conditions mirrored the language of their sourced counterparts exactly; they simply did not attribute the criticism to particular individuals. We refer to criticisms that quote an unnamed news outlet or an unnamed member of Congress as “unsourced criticisms” given that results were the same for all unsourced criticisms.

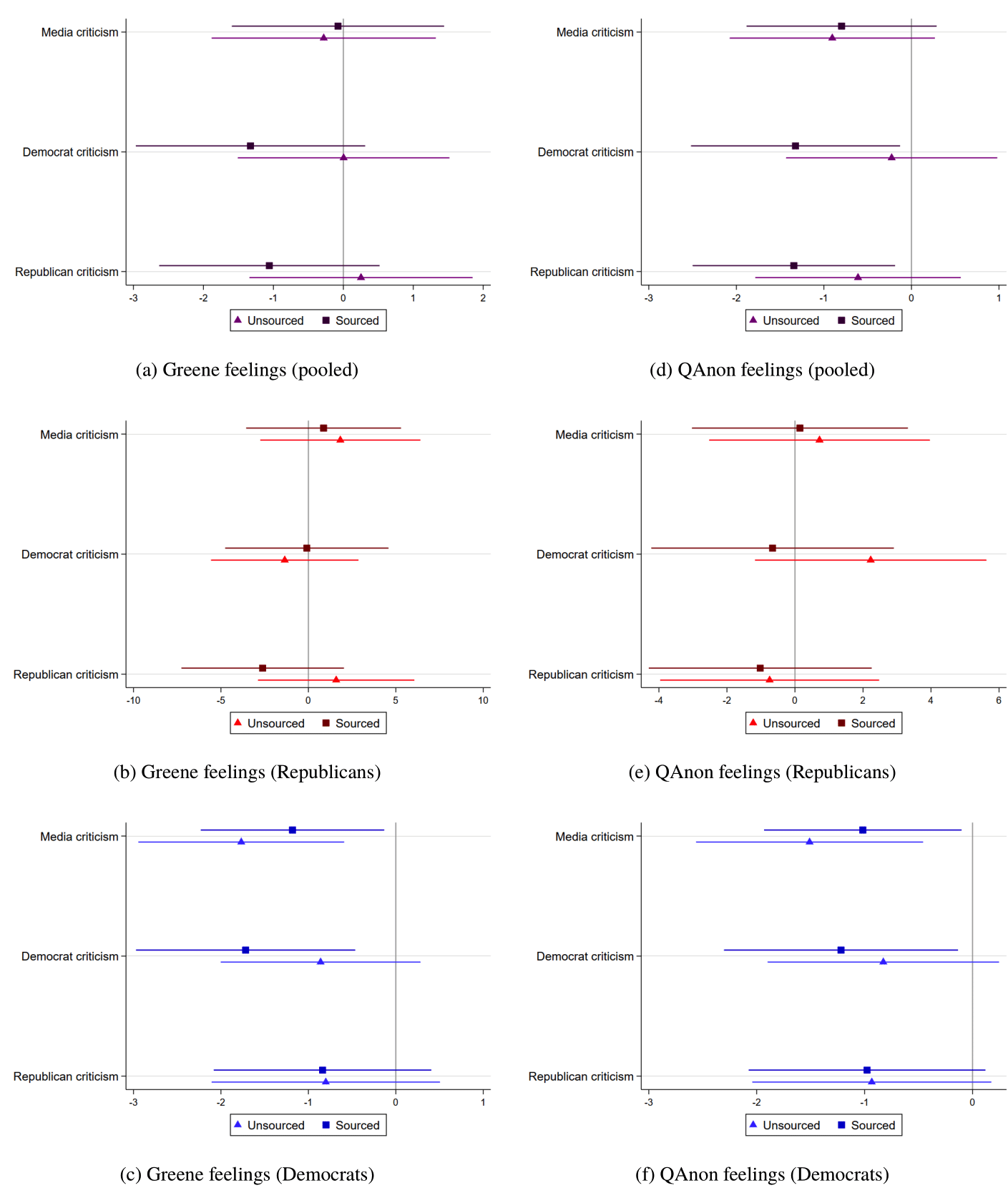

First, across our full sample of respondents, no criticism of Greene from any source affected respondents’ feelings toward Greene herself. Though Noble and Carlson (2022) found that both QAnon endorsements and critical media coverage of QAnon endorsements by hypothetical Congressional candidates diminish their popularity, we tested such coverage on the most high-profile QAnon supporter in real life and found null effects. These results, which we present in Figure 1a and Table B1 and Table B2,2Tables B1–B9 are in Appendix B. are consistent with prior research on how corrective information successfully reduces specific misperceptions but fails to change overall attitudes towards specific individuals (Nyhan et al., 2017; Swire et al., 2017). To determine if our overall null results could be attributed to offsetting effects on polarized Republicans and Democrats, we conducted exploratory analyses to estimate the impact of criticisms separately for respondents from each party. Figure 1b and Table B4 show that no criticism measurably reduced feelings toward Greene among Republicans. However, Figure 1c and Table B3 show that sourced Democrat criticism, sourced media criticism, and unsourced media criticism reduced feelings toward Greene for Democrats.

Second, only sourced criticisms from public officials reduced feelings toward QAnon, suggesting that public officials have a unique responsibility to criticize proponents of the QAnon conspiracy theory. Table B5 and Figure 1d show that unsourced criticisms (whether from a news outlet or a member of Congress) and sourced media criticisms failed to measurably change respondents’ feelings toward QAnon compared to a baseline article without criticism whereas criticism by a Republican or Democrat official reduced positive feelings toward the conspiracy theory compared to the baseline article.3Note, however, that although sourced partisan criticisms had statistically discernible impact relative to the baseline condition while unsourced partisan criticisms did not, sourced partisan criticisms are not statistically discernible from their unsourced partisan counterparts. See Figure 1d. In other words, rebukes of conspiracy theorists that quote specific officials can cause people to view conspiracy theories more negatively. The combination of results we observe suggests that attitudes toward particular conspiracy theories may be more mutable than attitudes toward individual conspiracy theorists.

Figure 1e and Table B8 show that no criticism reduced feelings toward QAnon for Republicans (see Table B6 for a full model with partisan interactions). This finding is noteworthy. Repeated calls for Republican officials to criticize Greene assume that Republican sources will be more persuasive to Greene’s supporters than would Democratic officials or media sources (e.g., Allen, 2021; Cillizza, 2021). Prior research, for example, has found that corrections of climate change misinformation from Republican officials are uniquely effective at convincing Republicans of the scientific consensus on climate change (Benegal & Scruggs, 2018). Criticisms of Greene by Republican officials might also be more effective in reaching QAnon adherents since Republicans are more likely to endorse the conspiracy theory (Russonello, 2021).4We note, however, that such co-partisan criticism is rare in practice, especially among Republican elites, who are seemingly less likely to directly condemn or criticize co-partisans who promote conspiracy theories than are their Democratic counterparts (Drum, 2010). In this context, criticisms from Republican officials might seem likely to fit the two necessary conditions for political persuasion that Lupia (2016) describes: attention capture and source credibility.

Yet, in our experiment, criticism of Greene by a Republican official did not affect Greene’s overall popularity and did not have measurably different effects from criticism from a Democratic official even among Republican respondents (Table B2). Zaller et al.’s (1992) classic “Receive-Accept-Sample” model would suggest that Republican members of the public form and adjust their political beliefs based on the Republican official consensus; as a result, we would expect to see that exposure to criticism of Greene by a Republican official reduces feelings toward Greene. The failure of Republican criticism to affect respondents’ feelings toward Greene suggests, by contrast, that a public figure’s popularity can prove resilient in the face of partisan signaling. Alternatively, the strength of partisanship as an identity may explain why Republicans are not willing to adjust their opinion toward a co-partisan elite (see Huddy et al., 2015; Mason & Wronski, 2018).5Of course, the strength of partisanship as an identity would also suggest that Republican members of the public would be more receptive to criticisms of Greene from Republican officials, which we did not observe.

Figure 1f and Table B7 show that the sourced Democrat criticism, sourced media criticism, and unsourced media criticism reduced feelings toward QAnon for Democrats. Democrats’ greater overall responsiveness to criticisms are noteworthy in that their baseline evaluations of QAnon are far lower than among Republicans to begin with. Here again, we do not find that exposure to sourced criticism is measurably more effective in moving attitudes than unsourced criticism. The source of a message is generally thought to have important effects on message persuasiveness, but many recent studies find limited or minimal effects (Chockalingam et al., 2021; Clayton et al., 2019; Nyhan & Reifler, 2010). Our study contributes to the empirical literature by providing a novel example of how source effects may differ across outcome variables.

Finally, we explored if exposure to criticism by a Democrat official or the media makes Republicans feel more positively toward Greene. Such a seemingly paradoxical phenomenon could occur for a variety of reasons. For instance, exposure to counter-attitudinal information could inspire a backfire or boomerang effect on attitudes (Hart & Nisbet, 2012), although recent research suggests such effects are rare (Guess & Coppock, 2020). Additionally, a portion of right-wing politics today centers around “owning the libs” by “infuriating, flummoxing or otherwise distressing liberals” (Robertson, 2021). This commitment can manifest itself in purposefully disagreeing with Democrats or the media and prompting their opprobrium. Greene herself touts the opposition she faces: “The D.C. swamp is against me. And the lying fake news media hates my guts. It’s a badge of honor. It’s not about me winning” (Rosenberg et al., 2020). Democrat or media criticism of Greene could simply be perceived as evidence of successful “lib-owning” on Greene’s part. All of these factors suggest that Republicans exposed to criticism of Greene from a Democrat official or the media might actually feel more positively toward her. However, we find no evidence of such a backfire effect. Although our tested criticisms of Greene failed to reduce respondents’ feelings toward Greene, there is also no indication that they make respondents feel more positively toward her (Table B1). This result is consistent with the Noble and Carlson (2022) finding that critical media coverage of QAnon endorsement does not provide electoral benefits for QAnon endorsers even among voters with low trust in the media.

Findings

Unless otherwise noted, the results below follow the analysis plan we preregistered prior to fielding the study (https://osf.io/vj6gw/?view_only=91c84e25811c450285015bb1d3d4a96a).

Finding 1: Exposure to criticism of Marjorie Taylor Greene does not make people feel more negatively toward her.

As Table B1 and Table B2 show, none of the respondents assigned to any of the six criticism conditions felt more negatively about Greene compared to respondents assigned to the baseline condition containing only a brief description of Greene without any criticism (p > .05 for all conditions).6As a result, exposure to sourced criticism of Greene did not make people feel more negatively toward her than exposure to unsourced criticism. Also, exposure to criticism of Greene by a Republican official did not make Republicans (or Democrats) feel more negatively toward her than exposure to unsourced criticism or criticism from other sources.

Exploratory analyses show that it is unlikely these results can be explained by either respondents’ lack of attention or by a floor effect in terms of respondents’ feelings toward Greene. First, 85% of respondents correctly responded to an attention check asking them which state Greene ran for office in, and 80% of respondents correctly responded to an attention check question asking if the article they read quoted any criticisms of her.7Substantially fewer respondents (only 41%) passed the third attention check asking which specific source was quoted criticizing Greene in the article they read, but respondents failing to understand the source of criticism would still not explain why some criticisms of Greene reduced the popularity of QAnon, but no criticisms of Greene reduced Greene’s popularity. Second, it is unlikely these results can be explained by a floor effect in terms of respondents’ feelings toward Greene: we ran exploratory analyses of people who rated their prior feelings toward Greene as higher than 10 out of 100, but results remained null.

We also conducted exploratory analyses to estimate the impact of criticisms separately for respondents from each party. To facilitate comparisons across models, in addition to reporting estimated effect sizes (and p-values), we also report estimated effect size in terms of standard deviations of the outcome variable. Figure 1c and Table B3 show that the sourced Democrat criticism, sourced media criticism, and unsourced media criticism reduced feelings toward Greene for Democrats (-1.718, p < .01, 0.110 s.d.; -1.182, p < .05, 0.076 s.d.; and -1.768, p < .01, 0.114 s.d., respectively). Figure 1b and Table B4 show that no criticism reduced feelings toward Greene for Republicans (p > .05 for all conditions).

Finding 2: Exposure to criticism from a Democrat or Republican official makes people feel more negatively toward QAnon, but exposure to unsourced criticism or media criticism of Greene has no effect on feelings toward QAnon.

Table B5 shows that respondents exposed to criticism from a Democrat or Republican official felt more negatively toward QAnon compared to respondents assigned to the baseline condition (-1.301, p < .05, – 0.061 s.d. and -1.242, p< .05, -0.058 s.d., respectively). All effect sizes are quite small, perhaps reflecting respondents’ brief exposure to the treatment. None of the respondents assigned to the other criticism conditions felt more negatively toward QAnon (p > .05 for all other conditions).

Finding 3: Though some criticisms made Democrats feel more negatively toward QAnon, none of the criticisms reduced feelings toward QAnon for Republicans.

We also conducted exploratory analyses to estimate the impact of criticisms separately for respondents from each party. As shown in Figure 1f and Table B7, the sourced Democrat criticism, sourced media criticism, and unsourced media criticism reduced feelings toward QAnon for Democrats (-1.219, p < .05, 0.082 s.d.; -1.017, p < .05, 0.068 s.d.; and -1.510, p < .01, 0.101 s.d., respectively). However, Figure 1e shows that no critical message reduced feelings toward QAnon for Republicans (p > .05 for all conditions).

Finding 4: Exposure to criticism from a Democrat official or the media does not make Republicans feel more positively toward Marjorie Taylor Greene.

Table B1 and Table B2 show that Republican respondents who were shown criticism of Greene by a Democrat official or the media did not feel more positively toward Greene compared to those assigned to the baseline condition (p > .05 for both conditions).

Methods

We collected data from 5,575 respondents surveyed by YouGov from March 9–23, 2021, using an online sample that was matched and weighted to approximate the population of U.S. adults. Table B9 shows a breakdown of the sample by partisanship.

As shown in Table 1, respondents were randomly assigned to one of seven conditions: a baseline article with a neutral description of Greene and six articles that include baseline information but also quote criticism of Greene based on her links to QAnon. All conditions include baseline information about Greene to make sure that respondents who are unfamiliar with her can meaningfully take part in the study.

We chose statements from these individuals for two reasons. First, to maximize external validity and avoid the deception inherent in researcher written statements attributed to real people, we presented real quotes from these current legislators and reporters. We sought statements that were as similar to each other as possible in length and content and selected these legislators and reporters because they made statements that fit our criteria. Second, we preferred legislators and reporters who were not well-known national figures toward whom respondents might have previously developed attitudes.

Each article provided a basic description of Greene and the results of her election. The six criticism treatments then included a quoted criticism of Greene. These criticisms detail her support of conspiracy theories and provide specific examples. To minimize issue-specific confounds, the language and substance of each criticism were matched closely, as were the status of the sources. The neutral baseline treatment briefly mentions QAnon but does not call it a conspiracy theory; the six treatment conditions, on the other hand, all clearly condemn Greene’s support of “the QAnon conspiracy theory.” The survey instrument is available in Appendix A.

To estimate the effect of criticisms from different sources, we needed a pure control condition with no criticism as well as control conditions with criticism but with no named source. (The control conditions are necessary because we would not have been able to isolate the source effect by comparing only against the pure control; see Chockalingam et al., 2021, on the importance of using such a baseline.) To maximize precision in our estimation of source effects, we included a different control condition for each sourced criticism. Using a single control condition for all the sourced criticisms would not have allowed us to isolate the source effects of interest because each sourced criticism contained a unique quote; in this way, we held the criticism constant while changing only its source.

Before reading the articles, respondents answered questions regarding demographics and their feelings and attitudes toward various people, institutions, and issues. They also rated Greene and QAnon using a feeling thermometer. Next, respondents read the article to which they were randomly assigned and answered attention checks about the sources of the criticism. (Individual respondents were not excluded from the analysis for inattention.) Respondents were asked again to fill out a feeling thermometer about Greene and QAnon.

Misinformation belief is difficult to accurately measure; online surveys in particular often overestimate levels of misinformation belief (see Altay et al., 2021; Clifford et al., 2019; and Sutton & Douglas, 2020). As a result, our survey measured feelings toward Marjorie Taylor Greene and toward QAnon using two simple feeling thermometers. Respondents were asked to click on a thermometer to give a rating, with 0 indicating “Very unfavorable” to 100 indicating “Very favorable.” Enders et al. (2022) used the same feeling thermometer to measure overall feelings toward QAnon as a movement.

Topics

Bibliography

Aliapoulios, M., Papasavva, A., Ballard, C., De Cristofaro, E., Stringhini, G., Zannettou, S., & Blackburn, J. (2021). The gospel according to Q: Understanding the QAnon conspiracy from the perspective of canonical information. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.08750

Allen, J. (2021, May 25). Republicans could expel Marjorie Taylor Greene. They won’t. NBC. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/republicans-could-expel-marjorie-taylor-greene-they-won-t-n1268531

Altay, S., Berriche, M., & Acerbi, A. (2021). Misinformation on misinformation: Conceptual and methodological challenges. PsyArXiv. https://psyarxiv.com/edqc8

Amarasingam, A., & Argentino, M.-A. (2020). The QAnon conspiracy theory: A security threat in the making. CTC Sentinel, 13(7), 37–44. https://ctc.westpoint.edu/the-qanon-conspiracy-theory-a-security-threat-in-the-making/

Benegal, S. D., & Scruggs, L. A. (2018). Correcting misinformation about climate change: The impact of partisanship in an experimental setting. Climatic Change, 148(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2192-4

Chockalingam, V., Wu, V., Berlinski, N., Chandra, Z., Hu, A., Jones, E., Kramer, J., Li, X. S., Monfre, T., Ng, Y. S., Sach, M., Smith-Lopez, M., Solomon, S., Sosanya, A., & Nyhan, B. (2021). The limited effects of partisan and consensus messaging in correcting science misperceptions. Research & Politics, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20531680211014980

Cillizza, C. (2021, May 24). What, exactly, would it take for republicans to walk away from Marjorie Taylor Greene? CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/24/politics/marjorie-taylor-greene-holocaust/index.html

Clayton, K., Davis, J., Hinckley, K., & Horiuchi, Y. (2019). Partisan motivated reasoning and misinformation in the media: Is news from ideologically uncongenial sources more suspicious? Japanese Journal of Political Science, 20(3), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109919000082

Clifford, S., Kim, Y., & Sullivan, B. W. (2019). An improved question format for measuring conspiracy beliefs. Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(4), 690–722. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz049

Drum, K. (2010, May 18). Birthers vs. truthers. Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2010/05/birthers-and-truthers/

Enders, A. M., Uscinski, J. E., Klofstad, C. A., Wuchty, S., Seelig, M. I., Funchion, J. R., Murthi, M. N., Premaratne, K., & Stoler, J. (2022). Who supports QAnon? A case study in political extremism. The Journal of Politics, 84(3). https://doi.org/10.1086/717850

Garry, A., Walther, S., Rukaya, R., & Mohammed, A. (2021). QAnon conspiracy theory: Examining its evolution and mechanisms of radicalization. Journal for Deradicalization, 26, 152–216. https://journals.sfu.ca/jd/index.php/jd/article/view/437

Guess, A., & Coppock, A. (2020). Does counter-attitudinal information cause backlash? Results from three large survey experiments. British Journal of Political Science, 50(4), 1497–1515. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000327

Hart, P. S., & Nisbet, E. C. (2012). Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Communication Research, 39(6), 701–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211416646

Hill, S. J., & Roberts, M. E. (2021). Acquiescence bias inflates estimates of conspiratorial beliefs and political misperceptions. http://www.margaretroberts.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/hillroberts_acqbiaspoliticalbeliefs.pdf

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000604

Lupia, A. (2016). Uninformed: Why people know so little about politics and what we can do about it. Oxford University Press.

Mason, L., & Wronski, J. (2018). One tribe to bind them all: How our social group attachments strengthen partisanship. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12485

Noble, B. S., & Carlson, T. N. (2022). Cueanon: The (not so) strategic endorsement of political conspiracy theories. https://benjaminnoble.org/files/papers/cueanon_noble_carlson.pdf

Nyhan, B., Porter, E., Reifler, J., & Wood, T. (2017). Taking fact-checks literally but not seriously? The effects of journalistic fact-checking on factual beliefs and candidate favorability. Political Behavior, 42, 939–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09528-x

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Robertson, D. (2021, March 21). How ‘owning the libs’ became the gop’s core belief. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/03/21/owning-the-libs-history-trump-politics-pop-culture-477203

Rosenberg, M., Herndon, A. W., & Corasaniti, N. (2020, March 11). Marjorie Taylor Greene, a QAnon supporter, wins House primary in Georgia. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/11/us/politics/marjorie-taylor-greene-qanon-georgia-primary.html

Russonello, G. (2021). QAnon now as popular in U.S. as some major religions, poll suggests. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/27/us/politics/qanon-republicans-trump.html

Steck, E., & Kaczynski, A. (2021, February 4). Marjorie Taylor Greene’s history of dangerous conspiracy theories and comments. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/02/04/politics/kfile-marjorie-taylor-greene-history-of-conspiracies/index.html

Sutton, R. M., & Douglas, K. M. (2020). Conspiracy theories and the conspiracy mindset: Implications for political ideology. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.02.015

Swire, B., Berinsky, A. J., Lewandowsky, S., & Ecker, U. K. (2017). Processing political misinformation: Comprehending the trump phenomenon. Royal Society Open Science, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160802

Vraga, E. K., & Bode, L. (2018). I do not believe you: How providing a source corrects health misperceptions across social media platforms. Information, Communication & Society, 21(10), 1337–1353. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1313883

Yokley, E. (2021, May 19). More than half of GOP voters now dislike Cheney after her ouster from leadership. Morning Consult. https://morningconsult.com/2021/05/19/cheney-stefanik-trump-gop-polling/

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge University Press.

Funding

We thank Dartmouth Undergraduate Advising and Research for funding support.

Competing Interests

No author had any potential conflicts of interest.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (STUDY00032068).

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QYAQLU

Acknowledgements

We thank Kayla Hamann and Jennifer J. Lee for assistance with study design.