Peer Reviewed

Framing disinformation through legislation: Evidence from policy proposals in Brazil

Article Metrics

0

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

This article analyzes 62 bills introduced in the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies between 2019–2022 to understand how legislators frame disinformation into different problems and their respective solutions. The timeframe coincides with the administration of right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro. The study shows a tendency from legislators of parties opposed to Bolsonaro to attempt to criminalize the creation and spread of health-related and government-led disinformation. This trend is explained by the Brazilian polarized democracy in a moment of crisis with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research Questions

- What common disinformation problems do legislators try to solve?

- How do legislators try to solve the disinformation problems they identify?

- How do the disinformation problems relate to legislators’ proposed solutions?

- Does party affiliation interfere with the legislators’ preferred solutions to disinformation problems?

RESEARCH NOTE SUMMARY

- This study examined 62 disinformation bills proposed by Brazilian legislators during the administration of right-wing politician Jair Bolsonaro (2019–2022). Bills were coded qualitatively following Entman’s (1993) framing approach according to the legislators’ problem definition and treatment recommendation.

- Results showed that most Brazilian legislators propose disinformation bills without specifying exactly what disinformation-related problem they are trying to tackle.

- Still, during the Bolsonaro administration and the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a proliferation of disinformation bills related to health issues, elections, and government-sponsored misleading information.

- Brazilian legislators also proposed defamation and hate speech bills justifying their importance under the claim of fighting disinformation.

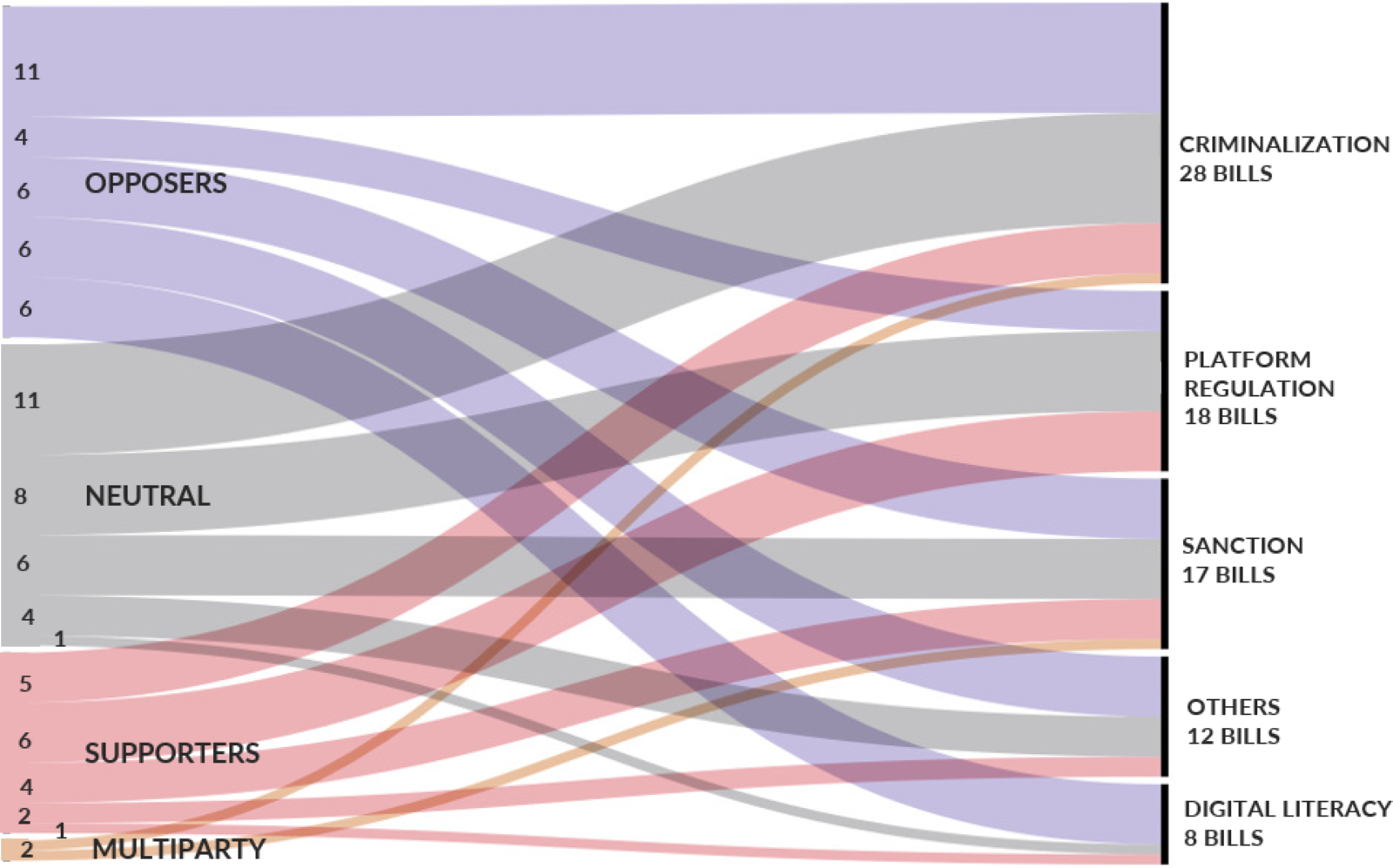

- Criminalization was the most common treatment recommendation proposed by lawmakers for disinformation problems, especially those related to health, defamation and hate speech, and government-led disinformation. Legislators from parties opposing the Bolsonaro administration were responsible for most of the bills proposing criminalizing solutions, especially trying to tackle government-led disinformation and health disinformation.

- The second most common remedy was platform regulation initiatives, a treatment that was usually proposed to tackle the problem of general disinformation. Such a treatment was mostly proposed by lawmakers from parties neutral to or aligned with Bolsonaro.

- Legislators from parties aligned with the Bolsonaro administration did not identify government-led disinformation as a problem.

- How legislators frame disinformation problems and their solutions is tightly connected with their struggle for truth and authority under polarized democracies.

Implications

The way politicians frame disinformation has a real-world impact: It affects the policies they create. Farkas and Schou (2018) demonstrate that fake news is a discursive signifier mobilized as part of political struggles to make certain agendas hegemonic. Under such understanding, different conceptions of fake news articulate political battlegrounds over reality. As Marda and Milan (2018) explain, fake news may be understood as “a battle of and over narratives” (p. 3). When politicians propose regulatory texts about disinformation, they make specific assumptions about what the problem is and how to solve it. How a lawmaker attributes meaning to disinformation follows their own ideology and worldview. Thus, political struggles around disinformation are embedded in seemingly neutral policy documents.

Regulation and policymaking are communicative processes (Popiel, 2020). Policy discourses and texts not only express strategic legislators’ goals. They foster specific ideological projects and are a site of contestation and conflict (Popiel, 2020; Lentz, 2011). The specific terms used in regulatory documents such as bills are employed strategically to define the contours of an issue (Napoli & Caplan, 2017). In the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies, disinformation bills are immersed in contrasting political agendas. As this study shows, legislators are framing disinformation problems and proposing treatments in their bills in ways that further political polarization instead of working to reduce it.

Misinformation is defined as false or inaccurate information shared without the intention to cause harm, while disinformation refers to false or inaccurate information shared with the intent to mislead (Bennett & Livingston, 2020; Epstein, 2020; Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017). In Portuguese, however, there is no widely used word for “misinformation.” In Brazil, the term desinformação refers to both intentional and unintentional inaccuracies and falsehoods.

Most Brazilian lawmakers do not clearly define disinformation in their bills. In their policy documents, disinformation is a signifier, a term that adapts to whatever their interpreters ascribe to it. Thus, the term is used by fundamentally different political projects that promote both antagonism among lawmakers and political conflicts (Farkas & Schou, 2018). The way the legislators frame disinformation in their bills is rooted in a deeper political struggle about truth during the government of right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro.

Brazil has a tradition of internet-related legislation and has been increasingly regulating disinformation (Keller, 2020). The Brazilian Civil Rights Framework for the Internet was approved in 2014 after almost seven years of multistakeholder debates where interested parties participated in public discussions. It was celebrated as one of the most innovative and human rights-oriented internet regulations in the world and represents a milestone of global internet governance (Rossini et al., 2015; Segurado, 2019). Brazilian internet-related regulation tends to impact international debates, and so may be the case of Brazilian disinformation regulation.

Disinformation tactics were deeply embedded in the 2018 election campaign of populist right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro (Baptista et al., 2019; dos Santos et al., 2019; Recuero & Gruzd, 2019). Bolsonaro holds a digital media apparatus that includes WhatsApp/Telegram supporter groups that is employed as a discursive mobilization mechanism. The content and frames that are posted and spread through this apparatus constitute a political tactic intended to influence people and build hegemony around Bolsonaro, thus asserting his political dominance (Cesarino, 2020). His populism spread across his supporters’ practices over digital media, furthering the polarization of social media discourse. Bolsonaro’s success is directly connected to his communication campaign based on the intense use of social media, especially through micro-targeting campaigns under the direct and indirect guidance of Bolsonaro’s administration (Cesarino, 2020; dos Santos et al., 2019; Evangelista & Bruno, 2018).

Disinformation was also a prominent topic during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time in which many online posts spread false and inaccurate information about the disease in the country (de Sousa Júnior et al., 2020). Such information was validated by politicians and governmental authorities attached to the Bolsonaro administration (Recuero & Soares, 2021). During the pandemic, health disinformation circulated more among radical right-wing groups of Bolsonaro’s supporters rather than any other political groups (Recuero et al., 2021; Soares et al., 2020). Far-right discourse around the pandemic framed COVID-19 as a political rather than a public health issue, with Bolsonaro’s supporters spreading disinformation about the disease to support the president’s polarizing health decisions about the pandemic (Soares et al., 2021).

Disinformation is connected to partisanship, as support for a certain political figure may be a strong motivator for spreading disinformation, fostering an “evil” versus “good” environment (Soares et al., 2021). The response to disinformation from lawmakers reflects the interconnectedness between disinformation and partisanship. For instance, many bills about disinformation created by lawmakers opposing Bolsonaro’s administration are aimed at problems connected to Bolsonaro’s use of digital media, with a focus on health and government-led disinformation. Dealing with these specific disinformation problems is important, but the nature of how to do so varies, including regulating social media platforms or fostering digital literacy programs. For example, lawmakers opposing Bolsonaro’s administration proposed the greatest number of penal solutions. Still, initiatives focused on criminalization tend to reinforce a polarizing narrative of “us” versus “them, the criminals.”

Moreover, legislators from parties aligned with Bolsonaro proposed bills tackling general disinformation mainly through remedies that dealt with how internet platforms work. The remedies were framed especially in terms of assuring freedom of expression and/or limiting anonymity online. Such platform regulation initiatives feed from and add to Bolsonaro’s digital populist characteristics (Cesarino, 2020), also fostering polarizing narratives.

Only about 1% of all bills introduced in the Brazilian legislative branch eventually became law (Marcelino & Helfstein, 2019). During the completion of this study, none of the 62 bills were turned into de jure policies. The problems and remedies I uncovered in this study make visible the political disputes around what disinformation is and what should be done about it from within policy documents. Research on disinformation policies might focus on disinformation effects and political disputes throughout the policymaking processes. I focused on mapping the discourses and symbolic dimensions around disinformation in the bills, which helps researchers and policymakers calibrate expectations and guide future policies on the issue.

In this study, I examined the ways that legislators perceived and conceptualized disinformation and tried to remedy it, implicitly or explicitly, according to their alignment with Bolsonaro’s political identity and ideology. I found that if they opposed Bolsonaro, they tended to tailor their strategies under punitive lenses, and if they favored him, they aimed to regulate internet platforms to ensure and protect specific political discourses, potentially those aligned to Bolsonaro’s digital populism strategies. Previous research has shown that support for Bolsonaro was a strong motivator for disinformation circulation in Brazil (Soares et al., 2021). Similarly, partisanship, manifested through alignment to the Bolsonaro administration, also influenced disinformation regulation.

Evidence

Bolsonaro’s opponents were the lawmakers who proposed the highest number of disinformation bills (35 in total), even though opposing parties have not made up the majority of the politicians in the Chamber of Deputies since 2018. Neutral parties have the most representatives, followed by the opposition, and then by Bolsonaro’s supporters. Neutral parties created 29 bills, of which 7 came from a single representative, Alexandre Frota, a polemic politician who publicly accused Bolsonaro’s sons of creating disinformation campaigns for their father (Bomfim, 2020). Supporters created 11 bills. Two bills had more than one author whose parties had contrasting standings about Bolsonaro. They were labeled “multiparty.”

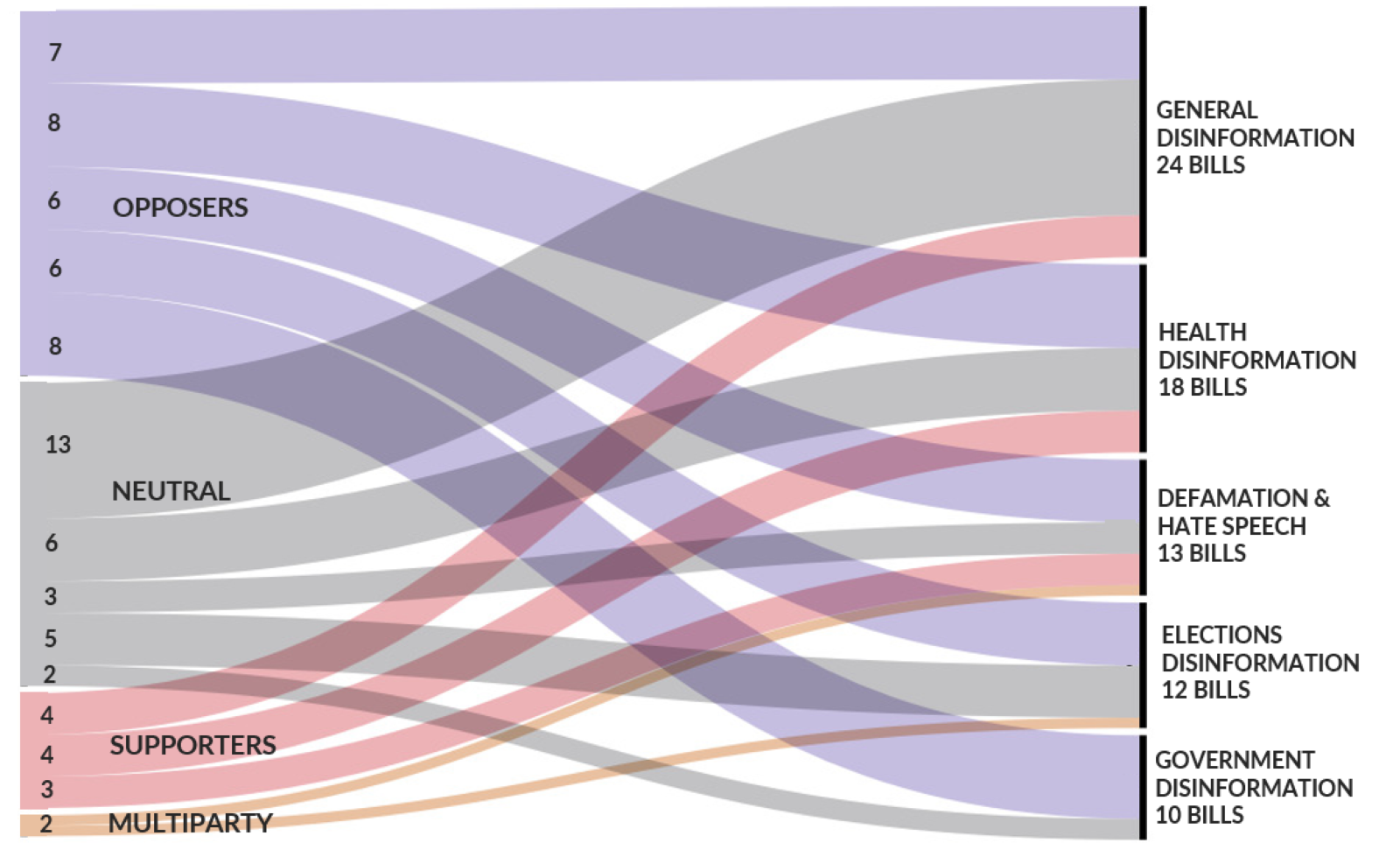

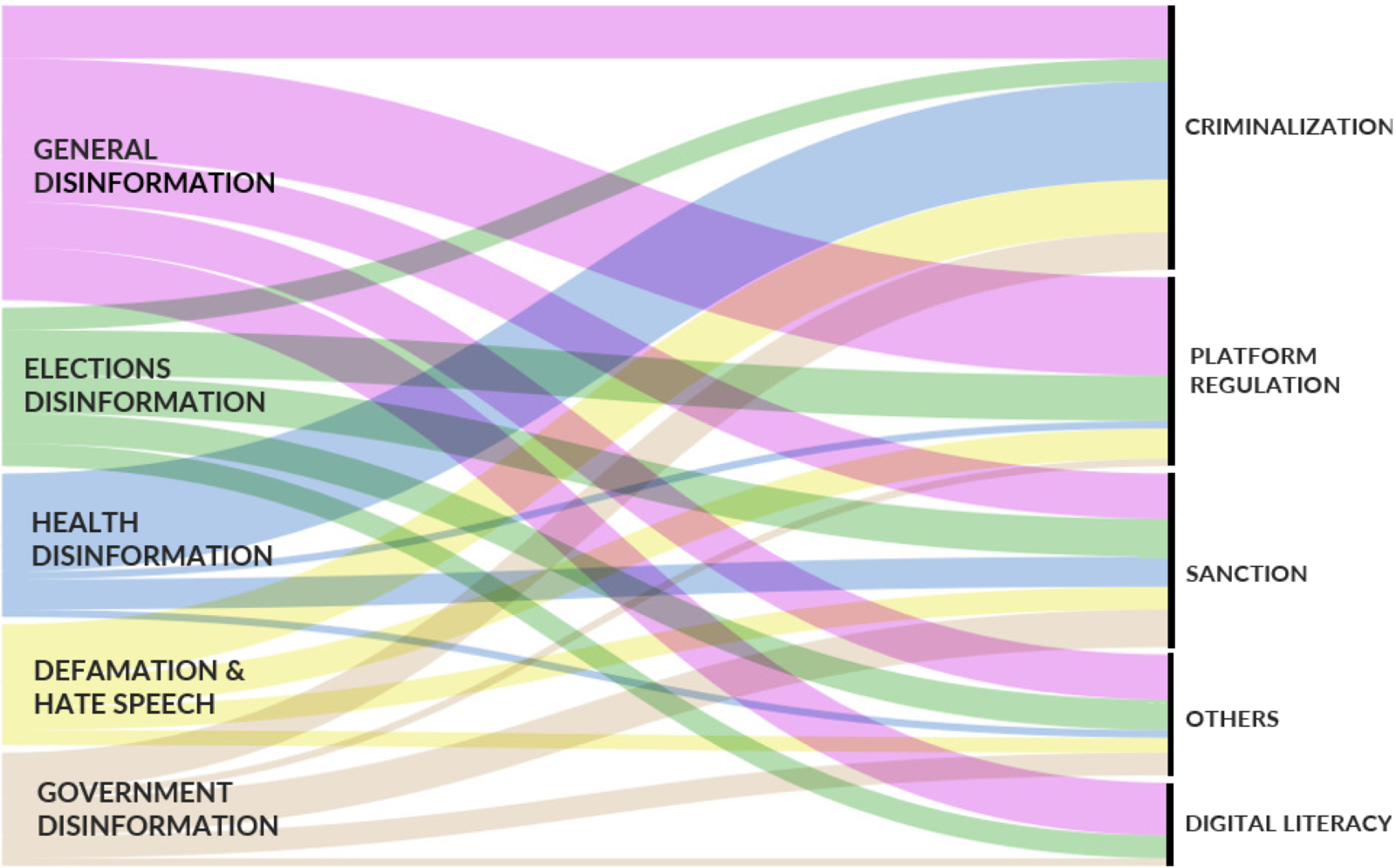

I identified how lawmakers framed disinformation in different problems and remedies. From a public policy perspective, frames are interpretations that tell “what needs fixing, and how it might be fixed” (Rein & Schön, 1996, p. 89). I found that general disinformation was the most cited problem among lawmakers (see Figure 1). In these cases, legislators did not identify a specific problem related to disinformation. They used general terms such as fake news and tried to tackle all problems at once. Health-related disinformation was the second most cited problem. These bills mainly tackled disinformation around the efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines, the proposal of unscientific health treatments, or the dismissal of guidelines from national and international health authorities. Defamation and hate speech was the third most cited problem, followed closely by election- and government-related disinformation, both usually related to misinformative practices seen during the campaign of Jair Bolsonaro for the 2018 election and the administration’s communication efforts about COVID-19.

Although many of the bills focused on specific problems, the majority of these policy documents lack clear definitions of disinformation. Moreover, some lawmakers mixed disinformation problems with other issues such as framing disinformation as defamation and hate speech. For instance, bill 241/2019 from a neutral party states that “the purpose of this proposition is to protect the subjective honor of people who are attacked every day through the internet.” When disinformation becomes a matter of subjective honor, defining the contours of what behavior is being targeted is more difficult. Authoritarian and surveilling measures, for example, may hide under the argument of tackling disinformation and elevating truth (Farkas & Schou, 2019).

The lawmakers’ preferred solution to disinformation was criminalization, turning the act of creating or spreading disinformation into a crime punishable under the country’s federal penal code. Such a preference prevailed especially among parties opposing or neutral to Bolsonaro. Platform regulation came thereafter. Remedies under this category included provisions that relate to how internet platforms work in Brazil. For example, some tried to end intermediary liability, proposed content moderation guidelines, or changed requirements for the creation of social media accounts (e.g., requiring the equivalent of a social security number to avoid anonymity online). Bills labeled under sanction mainly proposed fines for creating and spreading disinformation. Digital literacy bills proposed public awareness campaigns. Other solutions included miscellaneous things such as prohibiting governmental agencies from advertising on media known to spread disinformation or compelling news organizations to always disclose the names of journalists responsible for their publications.

When comparing the legislators’ problem identification and their proposed treatments (Figure 3), we see that penal remedies were especially popular on bills about COVID-19 and vaccine-related disinformation. Crises are fertile ground for disputes between frames and counter-frames (i.e., between interpretations and opposing interpretations of certain realities) concerning the nature and severity of a crisis, its causes, who is responsible for its occurrence or escalation, and what comes next (Boin et al., 2009). The Covid-19 crisis and the communication campaigns about the disease carried out by the Bolsonaro government stimulated the creation of bills tackling both health- and government-related disinformation.

Such measures were embedded in the political dispute against Bolsonaro’s supporters. In bill 1068/2020 from an opposing party, for instance, the legislators are clear in stating their intent to “punish exemplarily” (author’s translation) those who put the health of the entire population at risk by spreading disinformation, especially when misinformative communication comes from public authorities.

Bolsonaro’s opponents were the ones mostly concerned with health and governmental disinformation and who proposed criminalization remedies as solutions. The target of such bills, under the legislators’ understanding, would be malicious actors that were usually seen to be Bolsonaro’s supporters. It is the legislators’ diagnostic that those engaging in disinformation are Bolsonaro’s supporters who take part, voluntarily or involuntarily, in his political tactic of spreading misleading content to strengthen his figure and leadership while advancing his ideology. When the problem was identified as general disinformation, platform regulation was the most common solution.

Methods

To create the dataset, I searched the web archives of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies (Câmara dos Deputados) for the Portuguese word equivalent to disinformation, “desinformação,” considering all bills introduced between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2022. The time frame coincides with the duration of the Bolsonaro administration. This search limits this study to bills that mention the word “desinformação” or that were labeled by the Chamber of Deputies as dealing with disinformation.

I labeled the bills by the lawmaker’s party affiliation. Brazilian democracy is a multiparty system. In the 2018 elections, thirty parties got at least one politician elected to the Chamber of Deputies. I classified parties according to their endorsement in the 2018 presidential race. I labeled parties that openly supported Bolsonaro as “supporters.” Those who opposed him and openly advocated for the candidacy of Fernando Haddad from the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores) were labeled “opposers.” Parties labeled as “neutral” did not manifest their standing, explicitly said, they were neutral, or dismissed their affiliated politicians to endorse whatever candidate they preferred. I turned to news pieces that assembled the parties’ stance on the presidential elections to classify parties on this study’s database (Bertoni, 2018; “Posição dos partidos,” 2018). Throughout Bolsonaro’s administration, parties oscillated in their alignment with the government. Such oscillation is common in multiparty systems, especially in the Brazilian political model that researchers usually refer to as Coalitional Presidentialism (Abranches, 2018; Limongi & Figueiredo, 1998). Neutral parties, for example, sometimes moved closer to or farther from Bolsonaro during his administration. The decision to label parties according to their alignment with Bolsonaro at the moment of his election allowed me to pin down a time when parties were explicit and fixed on their stance.

I removed from the dataset bills that were pulled out from the legislative process by the legislators themselves and those labeled in the web archives as “desinformação,” but did not deal with disinformation as commonly identified in the literature (e.g., bills about ideological falsehood in identification documents). The remaining 62 bills were coded based on Entman’s (1993) definition of framing. In a communicative text, such as a bill of law, one chooses some aspects of reality over others, making them more salient, “in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (Entman, 1993, p. 52).

To identify the frames in the disinformation bills, I followed an elaborative top-down coding approach (Saldaña, 2008). I read through the bills and identified the overall problems legislators were trying to address as well as the treatment recommendations they had for each. After this deductive process of listing and classifying problems and treatments, I searched for patterned codes and found emergent discourses. I then merged similar problems and treatments under codes to offer a concise overview of the bills. The software NVivo was used to facilitate data coding and qualitative analysis. Table 1 in the Appendix is a codebook with examples of bills for each problem and treatment recommendation.

A second researcher, knowledgeable both in political communication and Portuguese, coded a random sample of half of the data set (31 bills) according to the codebook. The researcher was given access to the codebook and a brief explanation of each code. Following best practices on intercoder reliability reporting (Cheung & Tai, 2021; Coleman et al., 2024), I calculated the percentage of agreement by adding the rates that the independent researcher and I agreed upon and dividing it by the total number of ratings. We reached 86% of agreement.2Some studies that rely on qualitative coding report their intercoder reliability by using protocols such as Cohen’s kappa. However, a simple agreement percentage (total of agreements divided by the total of assessments) is appropriate for a small dataset and a study with different numbers of codes for each category (e.g., problem and remedy).

In Brazil, all bills have a legislative intent and share a similar layout. First, lawmakers introduce the provision proposed. This part may eventually become law. Then, they offer a justification for the importance of their bill. To understand the rationale of a legislator in their bill of law, I analyzed and coded both the solution being proposed and the argumentation behind it. In the coding process, a single bill can be categorized as having more than one problem and one treatment recommendation. The frames are not mutually exclusive.

Limitations and future agenda

The Brazilian federal legislative branch, called the National Congress (Congresso Nacional), follows a bicameral model. Bills from the Federal Senate (Senado Federal) database were not considered in this analysis. At the Federal Senate, elections are staggered so that either a third or two-thirds of senators’ seats are up for election every four years. At the Chamber of Deputies, however, all seats are open for election every four years. In this article, I look at a single place in time-the Bolsonaro administration- and focused on the Chamber of Deputies to analyze bills from lawmakers who engaged and got elected in said cycle. Future research could expand the scope of the study to address how other lawmakers, including senators who were not elected in the same cycle as Bolsonaro, framed disinformation. Moreover, this study focuses on frames around disinformation alone. Future studies could map out other terms and expressions lawmakers are employing to deal with disinformation-related problems.

Topics

Bibliography

Abranches, S. (2018). Presidencialismo de coalizão: Raízes e evolução do modelo político brasileiro [Coalitional presidentialism: Roots and evolution of the brazilian political model]. Companhia das Letras.

Baptista, E. A., Rossini, P., de Oliveira, V. V., & Stromer-Galley, J. (2019). A circulação da (des) informação política no WhatsApp e no Facebook [The circulation of political (mis)information on WhatsApp and Facebook]. Lumina, 13(3), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.34019/1981-4070.2019.v13.28667

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., Roberts, H., & Zuckerman, E. (2017). Study: Breitbart-led right-wing media ecosystem altered broader media agenda. Columbia Journalism Review, 3, 2017. https://www.cjr.org/analysis/breitbart-media-trump-harvard-study.php

Bennett, W. L. & Livingston, S. (2020). A brief history of the disinformation age: Information wars and the decline of institutional authority. In W. L. Bennett (Ed.), The disinformation age: Politics, technology, and disruptive communication in the United States (pp.153–168). Cambridge University Press.

Bertoni, E. (2018, October 11). Eleições 2018: Veja como os partidos se posicionaram no segundo turno [Elections 2018: See how parties positioned themselves in the second round]. Revista VEJA. https://veja.abril.com.br/politica/eleicoes-2018-veja-como-os-partidos-se-posicionaram-no-segundo-turno

Boin, A., ’t Hart, P., & McConnell, A. (2009). Crisis exploitation: Political and policy impacts of framing contests. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(1), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802453221

Bomfim, C. (2020, October 6). Frota depõe à PF e aponta relação direta de Eduardo Bolsonaro com difusão de fake news [Frota testifies to the Federal Police and highlights Eduardo Bolsonaro’s direct relationship with the spread of fake news]. TV Globo. G1. https://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/2020/10/06/frota-depoe-a-pf-e-aponta-relacao-direta-de-eduardo-bolsonaro-com-difusao-de-fake-news.ghtml

Cesarino, L. (2020). Como vencer uma eleição sem sair de casa: A ascensão do populismo digital no Brasil [How to win an election without leaving home: The rise of digital populism in Brazil]. Internet & Sociedade, 1(1), 91–120.

Cheung, K. K. C., & Tai, K. W. H. (2023). The use of intercoder reliability in qualitative interview data analysis in science education. Research in Science & Technological Education, 41(3), 1155–1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2021.1993179

Coleman, M. L., Ragan, M., & Dari, T. (2024). Intercoder reliability for use in qualitative research and evaluation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 57(2), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2024.2303715

de Sousa Júnior, J. H., Raasch, M., Soares, J. C., & de Sousa, L. V. H. A. (2020). Da desinformação ao caos: Uma análise das Fake News frente à pandemia do Coronavírus (COVID-19) no Brasil [From disinformation to chaos: An analysis of fake news in the midst of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Brazil]. Cadernos de Prospecção, 13(2), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.9771/cp.v13i2.35978

dos Santos, J. G. B., Freitas, M., Aldé, A., Santos, K., & Cunha, V. C. C. (2019). WhatsApp, política mobile e desinformação: a hidra nas eleições presidenciais de 2018 [WhatsApp, mobile politics and disinformation: the hydra in the 2018 presidential elections]. Comunicação & Sociedade, 41(2), 307–334. https://doi.org/10.15603/2175-7755/cs.v41n2p307-334

Entman, R.M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Epstein, B. (2020). Why it is so difficult to regulate disinformation online. In W. L. Bennett (Ed.), The Disinformation age: Politics, technology, and disruptive communication in the United States (pp.190–210). Cambridge University Press.

Evangelista, R. & Bruno, F. (2019). WhatsApp and political instability in Brazil: Targeted messages and political radicalisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1434

Farkas, J., & Schou, J. (2018). Fake news as a floating signifier: Hegemony, antagonism and the politics of falsehood. Javnost, 25(3), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2018.1463047

Farkas, J., & Schou, J. (2019). Post-truth, fake news and democracy: Mapping the politics of falsehood. Routledge.

Keller, C. I. (2020). Don’t shoot the message: Regulating disinformation beyond content in Brazil. [Online workshop]. Tech Companies and the Public Interest. The Hertie School of Governance. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199576081.003.0007

Limongi, F., & Figueiredo, A. (1998). Bases institucionais do presidencialismo de coalizão [Institutional bases of coalitional presidentialism]. Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política, 44, 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-64451998000200005

Lentz, R. G. (2011). Regulation as linguistic engineering. In R. Mansell & M. Raboy (Eds.), The handbook of global media and communication policy (pp.432–448). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444395433.ch27

Marcelino, D. (2019, September 12). Menos de 1% das propostas apresentadas no Congresso viram lei [Less than 1% of the proposals presented in Congress have become law]. JOTA Notícias. https://www.jota.info/dados/congresso-projetos-leis-12092019

Marda, V., & Milan, S. (2018). Wisdom of the crowd: Multistakeholder perspectives on the fake news debate. Internet Policy Review series. Annenberg School of Communication. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3184458

Napoli, P., & Caplan, R. (2017). Why media companies insist they’re not media companies, why they’re wrong, and why it matters. First Monday, 22(5), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i5.7051

Popiel, P. (2020). Let’s Talk about regulation: The Influence of the revolving door and partisanship on FCC regulatory discourses. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 64(2), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2020.1757367

Recuero, R. D. C., & Soares, F. B. (2021). O discurso desinformativo sobre a cura da COVID-19 no twitter: Estudo de caso [The disinformative discourse about the cure for COVID-19 on Twitter: A case study]. E-Compós: Revista da Associação Nacional dos Programas de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação, 24, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.30962/ec.2127

Recuero, R., & Gruzd, A. (2019). Cascatas de “Fake News” políticas: Um estudo de caso no Twitter [Cascades of political “Fake News”: A case study on Twitter]. Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação e Semiótica, 41. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-25542019239035

Recuero, R., Soares, F. B., & Zago, G. (2021). Polarization, hyperpartisanship, and echo chambers: How the disinformation about COVID-19 circulates on Twitter. Contracampo-Brazilian Journal of Communication, 40(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.22409/contracampo.v40i1.45611

Rein, M., & Schön, D. (1996). Frame-critical policy analysis and frame-reflective policy practice. Knowledge and Policy, 9(1), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02832235

Rossini, C., Cruz, F. B., & Doneda, D. (2015). The strengths and weaknesses of the Brazilian Internet bill of rights: Examining a human rights framework for the internet [Issue Paper Series No 19]. Global Commission on Internet Governance. Centre for International Governance Innovation. Royal Institute of International Affairs. https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/no19_0.pdf

Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Segurado, R. (2019) The Brazilian civil rights framework for the Internet: A pioneering experience in Internet governance. In A. Pereira Neto & M. Flynn (Eds.), The internet and health in Brazil (pp. 27–45). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99289-1_3

Soares, F. B., Viegas, P., Bonoto, C., & Recuero, R. (2021). COVID-19, desinformação e Facebook: circulação de URLs sobre a hidroxicloroquina em páginas e grupos públicos [COVID-19, Disinformation and Facebook: Circulation of URLs about hydroxychloroquine on public pages and groups]. Galáxia, 46. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-2553202151423

Soares, F. B., Recuero, R., Volcan, T., Fagundes, G., & Sodré, G. (2021). Research note: Bolsonaro’s firehose: How Covid-19 disinformation on WhatsApp was used to fight a government political crisis in Brazil. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-54

Posição dos partidos: quem apoia Haddad ou Bolsonaro no 2º turno? [Parties’ positions: who supports Haddad or Bolsonaro in the 2nd round?]. (2018, October 16). Gazeta do Povo. https://especiais.gazetadopovo.com.br/eleicoes/2018/graficos/partidos-quem-apoia-haddad-bolsonaro-2-turno/

Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making [Report DGI(2017)09]. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-researc/168076277c

Funding

No funding has been received to conduct this research.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethics

The data for the project was obtained from publicly available sources at the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies website.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HVVPEA.

Acknowledgements

I thank the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review editors and reviewers for their thoughtful recommendations. I also extend my gratitude to Pedro Abelin, who coded a sample of the dataset, to Dr. Saif Shahin, and those at AU School of Communication, the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC), and the Research Group on Society-State Relationships (Resocie) at the University of Brasília who have read previous iterations of this work.