Peer Reviewed

Retracted: Disinformation creep: ADOS and the strategic weaponization of breaking news

Article Metrics

7

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

In this essay, we conduct a descriptive content analysis from a sample of a dataset made up of 534 thousand scraped tweets, supplemented with access to 1.36 million tweets from the Twitter firehose, from accounts that used the #ADOS hashtag between November 2019 and September 2020. ADOS is an acronym for American Descendants of Slavery, a largely online group that operates within Black online communities. We find that the ADOS network strategically uses breaking news events to discourage Black voters from voting for the Democratic party, a phenomenon we call disinformation creep. Conversely, the ADOS network has remained largely silent about the impact of the novel coronavirus on Black communities, undermining its claims that it works in the interests of Black Americans.

Editorial Staff Note

This article was retracted on December 20th, 2021. Read the retraction note here.

This essay was published as part of a Special Issue on “Disinformation in the 2020 Elections,” guest-edited by Dr. Ann Crigler (Professor of Political Science, USC) and Dr. Marion R. Just (Professor Emerita of Political Science, Wellesley College). You can find the special issue following this link. Please direct any inquiries about this essay to the corresponding author at mnkonde@law.harvard.edu

Research Questions

- How have disinformation tactics sought to suppress Black American voter turnout during the 2020 general election?

- How have references to Black American struggles and enduring stereotypes framed disinformation targeting Black voters on Twitter?

Essay Summary

- We carried out a descriptive content analysis of tweets from Twitter accounts that used the #ADOS hashtag, using a combination of 534 thousand scraped tweets and 1.36 million tweets from the Twitter firehose, between November 2019 and September 2020.

- We document how the ADOS network leverages Black identity and breaking news to implicitly or explicitly support anti-Black political groups and causes, strategically discouraging Black voters from voting for the Democratic party.

- The ADOS network has remained largely silent about the impact of the novel coronavirus on Black communities, undermining its claims to prioritize the interests of Black Americans.

- We give the name disinformation creep to this method of combining legitimate grievances along with slight factual distortions and reinterpretations of breaking news events that culminate in a contradictory worldview, at odds with the interests the worldview purports to support.

- We theorize that disinformation creep is a general phenomenon, wherein marginalized communities whose interests and legitimate grievances are ignored by mainstream narratives are targeted by misinformation narratives.

Implications

An investigation by the Channel Four News Investigations Team (2020) revealed how the 2016 Trump campaign spent about $60 million dollars, targeting 3.5 million Black Americans with six million versions of targeted Facebook ads attempting to dissuade them from voting with messages about how Hillary Clinton would be “bad” for Black people. This campaign may have successfully reduced Black voter turnout, even ultimately swinging the Presidential election to a candidate who has open courted white supremacist groups (Klein, 2018) and whose deliberate and predictable inaction around the crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately harmed the health and prosperity of Black populations.

That is, instead of attempting to win over Black voters, the Trump campaign’s strategy was to use disingenuous rhetoric to discourage civic participation entirely. The strategy’s likely success in 2016 made it certain it would be used in the 2020 election as well, and likely future elections too. Since free speech protections may take precedence (Bazelon, 2020), even if the intent and effect of such rhetoric is voter suppression, it is important to understand these narratives in order to combat them.

The ADOS political movement was founded in 2016 by former Democratic staffer Yvette Carnell and lawyer Antonio “Tone” Moore to represent the interests of what they identify as a distinct group of Black Americans: those descended from Africans enslaved in the U.S. in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, specifically excluding the descendants of those enslaved outside of the U.S., as well as Black Africans. Although not entirely accurate, in this article, the demographic group will be referred to as “native-born Black Americans”1Most precisely, Black American descendants of persons enslaved in the US (Richardson et al., 2020). This is a group that excludes white-identified American descendants of (Black) persons enslaved in the U.S., as well as more recent immigrants who are either descended from persons enslaved elsewhere (such as Jamaica, Haiti, or Brazil) or from Africa. This group of Black Americans has a specific legal claim to reparations from the United States government for slavery and segregation, unlike other groups, whose reparations claims for slavery would be to other bodies, and who largely immigrated after the end of segregation (Darity & Mullen, 2020). and “ADOS” will be used to refer to the organization and online network.

ADOS has self-organized regional chapters across the United States, some of which have in-person meetings, and one national conference was held in October 2019 which boasted then-presidential candidate Marianne Williamson and Harvard professor Cornell West in attendance (Stockman, 2019a). The group is perhaps most notable for its aggressive online trolling (Stockman, 2018b). Their activism for reparations comes long after that of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA), a Washington DC-based think tank who have been advocating for the payment of reparations for Black Americans since 1987. However, ADOS and N’COBRA are at odds (N’COBRA, 2019), in that ADOS rejects calls for reparations not narrowly focused only for native-born Black Americans and the N’COBRA strategy of working with and within the Democratic party.

ADOS has been reported on in mainstream outlets (Lynn, 2020; Stockman, 2019a), and its rhetoric and internal dynamics have been analyzed and critiqued within the larger Black cultural conversation from various pan-Africanist and other perspectives (Adjei-Kontoh, 2019; Aiwuyor, 2020; Crawford, 2019; Martin, 2020). Here, we focus on the implications of ADOS messaging for civic participation and voting in terms of what we call disinformation creep, a phenomenon in which legitimate positions and information are slightly distorted and reinterpreted to leverage a separate position entirely, one that may even be at odds with the interests that it purports to support. We theorize that this is a general phenomenon, but one particularly effective at targeting marginalized groups whose systematic neglect by mainstream media and political parties creates openings for alternative narratives.

Disinformation creep relates to a long history of Russian exploitation of American racial tensions to advance their foreign policy goals (Qui, 2017). From the Scottsboro Boys in 1932 (Iofee, 2017) to Operation Infektion in the 1980s (Rid, 2020) and narratives around COVID-19 (Swan, 2020), Russia has sought to exploit US injustices and Washington’s failures to argue that the United States should lose its position as a world leader. In 2016, Russia used identity-based campaigns and agents posing as Black Americans (Danner, 2018) to try and discourage Black voters from supporting Hillary Clinton (Aceves, 2019; Albright, 2017; Mueller et al., 2019; SOVAW, 2018). Memorably, the Senate Intelligence Committee report stated that “that no single group of Americans was targeted by IRA information operatives more than African-Americans. By far, race and related issues were the preferred target of the information warfare campaign designed to divide the country in 2016” (Select Committee on Intelligence, 2019, p. 6). Russian campaigns are likely indifferent to whether they help or hurt Black Americans, although the involvement likely helped a struggle for justice in the 1930s but hurt Black Americans in 2016.

It is then natural to suspect ADOS of being propped up by Russian activity like similar campaigns in 2016 (Alba, 2020; Ward et al., 2020). But the ADOS network insists all ADOS content is organic, fiercely rejecting even the possibility of Russian origins for any ADOS content (Chavéz, 2019). But rather than center our argument on the question of inauthentic activity, we instead focus on the underlying narrative of ADOS, one of Black voter suppression (SOVAW, 2020), which can be exploited by domestic actors as much as foreign ones seeking to suppress voter turnout (Graham, 2018). We argue that ADOS strategically leveraged breaking news events that highlight the (very real) impacts of structural racism on and failures of the federal government to support native-born Black Americans, and used them as entry points to argue why native-born Black Americans should either not vote for the top of Democratic ticket, or vote Republican, or (in the case of a related group, Foundational Black Americans) not vote at all in the 2020 presidential election. This is disinformation creep.

Furthermore, we believe that the disingenuity of this rhetoric is shown by the lack of concern with the continuing wave of the COVID crisis, which is disproportionately devastating Black communities (Khazanchi et al., 2020). The competing messages—that not voting will build the political power of Black communities versus voting for (among other interests) a platform of effective and equitable management of COVID-19 that will save Black lives and stem the economic hardship (Gould & Wilson, 2020)—are akin to the “information fog,” creating a profusion of conflicting information to undermine the ability of a society to establish a factual reality (Russian Intervention in European Elections, 2017) employed by KGB disinformation agents (Ellik & Westbrook, 2018).

The leading users of the #ADOS hashtag come from Black American communities, and so, unlike foreign actors and out-group members, they are fluent in African American Vernacular English (Luu, 2020) and Black American culture (Freelon et al., 2018), and they personally understand the pain associated with living with structural racism and intergenerational trauma. But it is also a nativist and populist movement, putting a focus on immigrants for supposedly taking away scarce resources, rather than looking at power structures that allocate those resources in the first place.

ADOS leverages legitimate moral and legal arguments for reparations and grievances about the failure of the Democratic party to adequately support one of its most loyal and critical voting blocs but brings in immigration. Including immigration as a distinguishing factor is justified by legitimate statistics around how Black immigrants have much higher levels of wealth and educational achievement, as well as better health outcomes (Brown et al., 2017) versus native-born Black Americans, differences that can indeed be directly attributed to racial stress and intergenerational trauma that started in slavery and persists today (Doamekpor & Dinwiddle, 2015), despite evidence that this divergence is the fault of treatment by the dominant white culture (Iheduru, 2013), and not of the immigrants. Animating ADOS grievances are the negative attitudes that Black immigrants can hold about native-born Black Americans (Nsangou & Dundes, 2018; Telusma, 2019), as well as perceptions of dominant cultural narratives favoring those who are apart from the direct legacy of the trauma of slavery and the indictment that legacy presents for the moral foundations of the United States.

ADOS also resents what it sees as justice claims of other groups being prioritized over those of native-born Black Americans. However, it sees the solution as narrowly advocating for the interests of native-born Black Americans alone, and rejecting any solidarity or larger coalitions (N’COBRA, 2020), including trans-national movements for reparations or coalitions that address how systematic racism also lethally affects Black immigrants and other groups. Significantly, Carnell previously sat on the board of Progressives for Immigration Reform (PFIR), a subsidiary of the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), which has been identified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center (Boehlert, 2019) because of its violent opposition to foreign nationals living in the United States.

The ultimate impact that ADOS may have had on the 2020 election will be hard to ascertain; however, it did have a notable media moment when rapper Ice Cube talked with the Trump campaign about his “Contract With Black America” in October, which was heavily based on ADOS ideas (Watts, 2020). The Trump campaign used this moment to claim approval from Ice Cube, an example of disinformation creep in trying to distract from Trump’s often outright racism and deep hostility and opposition to the far broader Movement for Black Lives coalition.

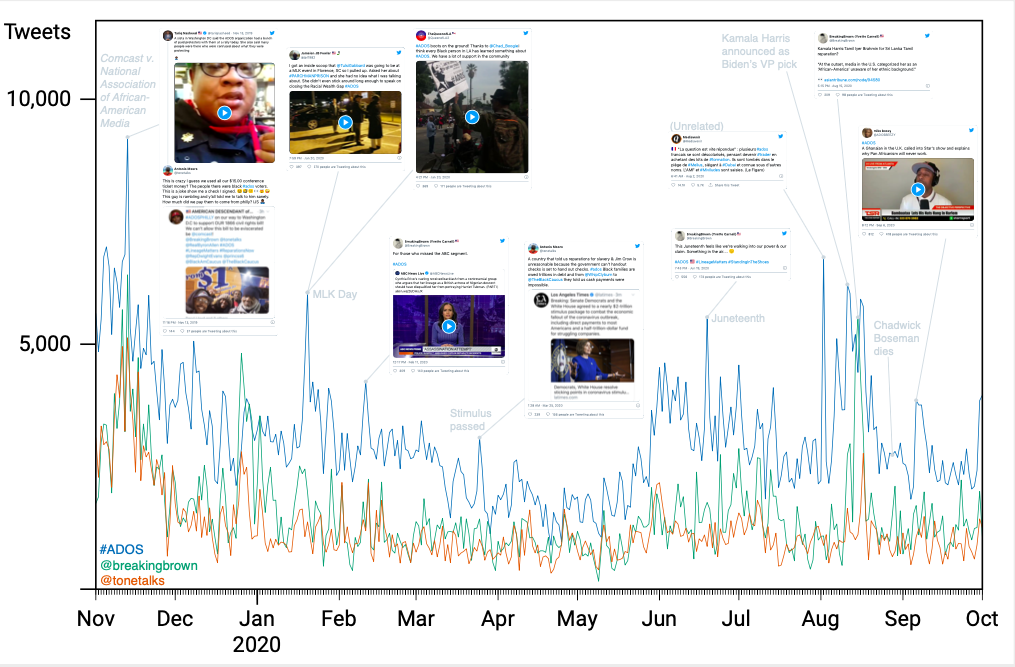

We scraped a set of 534 thousand tweets using “#ADOS” or two related terms (“#LineageMatters,” “AmericanDOS,” which we found were not widely used) and posted between November 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020, running analyses on weekly subsets to first understand the content of the ADOS network and to select tweets on which to carry out descriptive content analysis. The status_ids of the tweets, and scripts for both collection and analysis, are available from the Harvard Dataverse (Nkonde et al., 2021). For having accurate counts of daily frequencies to compare to real-world events, we supplemented this scraped set with access, via a third-party service, to a set of 1.36 million tweets pulled from the Twitter firehose. This includes a total of 1.1 million tweets using the #ADOS hashtag that were publicly visible on Twitter as of the end of 2020. These frequencies are shown in Figure 1.

Findings

Finding 1: Disinformation creep seeks to push followers to the right on immigration.

In a 2020 political landscape complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic and tangible racial animus, disinformation creep tactics include using right-wing talking points and news stories to promote Black voter disenfranchisement.

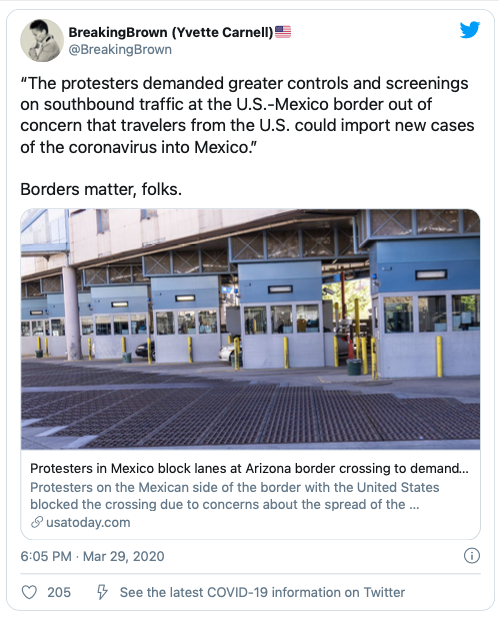

In Figure 2, a tweet from Carnell, she uses the health crisis to double down on ADOS’s anti-immigration stance. In the first case, the changing dynamics at the U.S./Mexico border are used as a framing tool to suggest Black American issues are distinct from issues in other communities of color. In using the phrase “borders matter” phrase as a play on the phrase “Black Lives Matter,” Carnell engages in disinformation creep by using anti-racist messaging to support racist policies. Linking Black Lives Matter with ADOS in the above tweet is notable in its contradiction, given that the Movement for Black Lives is a multiracial, immigrant-affirming coalition that uses on- and offline organizing to advocate for the passage of anti-racist policies around immigration (Parker et al., 2020; Winsor, 2016).

Finding 2: Disinformation creep extends to popular culture.

Not only does ADOS’se disinformation creep use political news events to spread the ADOS network’s message of voter disengagement, but contributors to ADOS content also capitalize on their in-group status by incorporating popular culture into their messaging.

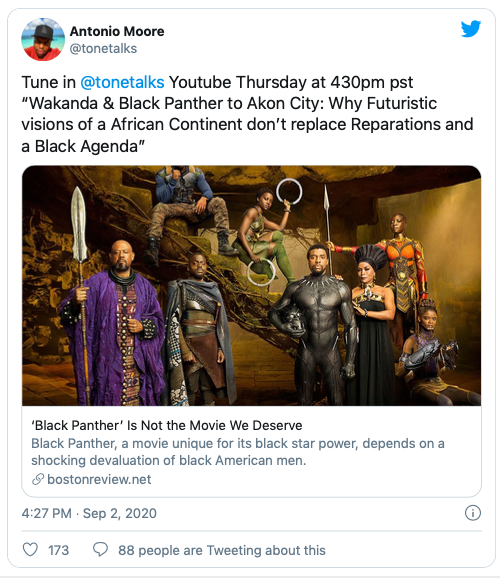

In Figure 3, Moore promotes an episode of his YouTube talk-show that aired shortly after the sudden news of actor Chadwick Boseman’s death after a four-year-long fight with colon cancer (Lewis, 2020). Moore uses Black Panther, an Oscar-nominated film in which took in over $1 billion at the box office with Boseman in the lead role, to double-down on ADOS’s stance on reparations rather than express shock at Boseman’s untimely passing (McClintock, 2018). Given the outpouring of shock and grief at the news of Boseman’s death, ADOS choosing to amplify a critique of the movie is somewhat unexpected. In contrast to the centrality of Boseman’s passing in the larger Black cultural conversation, and despite @chadwickboseman being a native-born Black American, his passing on August 28, 2020, barely registered in the ADOS conversation, with Figure 1 showing the low number of #ADOS tweets on the day he died. The strong pan-Africanist message and imagination of the film instead made it a target.

Finding 3: Disinformation creep focused on the 2020 presidential race.

On August 16, 2020, ADOS founder Yvette Carnell was featured on CNN’s United Shades of America, a weekly television series about racism in America hosted by W. Kamau Bell, where she explained ADOS’s stance on the 2020 election. During her interview with Bell, Carnell says that ADOS does not support Democrats who do not commit to its vision for reparations, stating “we haven’t encouraged anyone to stay home but we have encouraged Democratic down-ballot. Vote for Democrats but top of the ticket, there’s no love unless you come to us and say, ‘We have a reparations plan which includes financial outlays. We have a budget attached to this. That’s what we’re pushing for’” (Brown, 2020).

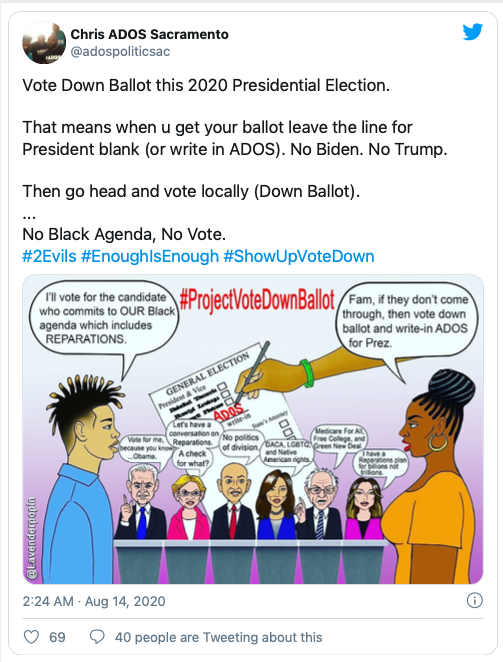

A tweet from @adospoliticsac encourages users in the ADOS network to engage in the #ProjectVoteDownBallot campaign, and describes how to cast a ballot in the 2020 election without participating in the presidential race (see Figure 4). Carnell’s focus on holding politicians to ADOS’s values on reparations and tweets like the one above that encourage down-ballot voting pose a tangible threat to Black voter turnout.

In the 2016 presidential election, two percent of the approximately 129 million ballots cast skipped the presidential race, and specifically, at least 70,000 black voters (Harvey, 2016), showing an increase across states by an average of 2.5 times the number of down-ballot votes from 2012; and in Michigan, a battleground state, the number of down-ballot votes in 2016 was over 75,000, greater than the 10,000-vote margin of victory by which Donald Trump won the state (Bump, 2016).

Finding 4: ADOS’s disinformation creep was focused on suppressing the Black vote for the Democratic Party.

Most Black voters vote Democrat (White & Laird, 2020), but ADOS argues that in order to secure reparations for native-born Black Americans, they must abandon the Democratic party, a call to action shared by Black conservative personality and microcelebrity Candace Owens (Carnell, 2019). Carnell often cites Democrats’ apparent inability to make progress on this issue as a reason for this stance, despite a 2019 panel hearing in a Democrat-led House of Representatives on reparations for slavery (Stolberg, 2019).

Our historical Twitter data shows that mentions of @joebiden and @kamalaharris appear more frequently than @realdonaldtrump in our dataset. This supports the idea that ADOS is focused heavily on the Democratic voters during the lead up to the November election. Amongst the top 20 accounts mentioned by ADOS accounts in our dataset, @kamalaharris was the most mentioned politician.

In Figure 5, Carnell employs disinformation creep by reacting to the announcement of Kamala Harris as Joe Biden’s running mate in the 2020 presidential election. Carnell’s critiques of both Biden and Harris’ records on criminal justice by referring to them as “Jim Crow Joe” and “Top Cop” respectively are in line with ADOS’s distrust of the Democratic Party. Carnell also calls into question Harris’s ethnic heritage by repeating xenophobic attacks on former president Barak Obama’s heritage and applying them to Harris. She disparages the fact that neither politician is an American Descendant of Slavery, suggesting that their ethnic identity is yet another example of native-born Black Americans being sidelined and marginalized by the Democratic party in favor of immigrant groups and taking away resources (in this case, representation on a presidential ticket and subsequently being in a position of power). There is also reference to Harris’s background as a prosecutor, but it is her identity (rather than her policies) that is central to their rejection of the Democratic ticket. Again, this both denies the possibility of solidarity or coalitions across identities, and asymmetrically holds only Democratic powerbrokers to account while not addressing the impacts on the lives of native-born Black Americans.

Methods

The tweets in Figures 2-5 are examples of breaking news stories which led to a spike of activity within the ADOS network (which do not necessarily correspond to the overall spikes shown in Figure 1). We then chose the ones that best illustrated the point we wanted to make.

The findings presented above are based on a combination of methods. First, we used GetOldTweets3 (Mottl, 2019), a Python 3 library and command line tool utility, to retrieve tweets beyond the official Twitter API time constraints.2In September 2020, Twitter removed the /i/search/timeline endpoint (Dinco, 2020), making GetOldTweets3 no longer work. For reproducing our initial analysis, we used snscrape (https://github.com/JustAnotherArchivist/snscrape) in its place. Since this tool is less tested and poorly documented, we extracted status_ids from the scrape it returned, and then got those tweets again via rtweet. These queries were for tweets that mentioned “ADOS,” “LineageMatters,” or “AmericanDOS,” and the total search from which the findings here are drawn spanned from November 1, 2019 to September 30, 2020 (inclusive). We have provided both scripts to reproduce this scrape, as well as the status_ids of the scraped tweets (which, in accordance with the Twitter Developer terms of service, are the only thing that may be shared),3“Academic researchers are permitted to distribute an unlimited number of Tweet IDs and/or User IDs if they are doing so on behalf of an academic institution and for the sole purpose of non-commercial research.” (Twitter, 2020). in a publicly available repository on the Harvard Dataverse (Nkonde et al., 2021).

To analyze these tweets, we used a method called computational grounded theory (Nelson, 2020), a three-step approach to examining large volumes of text data that combines computational methods with in-depth qualitative analysis. We used the rtweet R library (Kearney, 2020) to gather timelines and follower lists, and networks. Following descriptive statistics, we then used structural topic modeling (STM) (Roberts, 2019) to estimate the general thematic content of the tweets. In the second step, we conducted a thorough deep read of all topics to categorize themes of interest, using the output from the STM as a guide (Rodriguez & Storer, 2020) while reading tweets. The qualitative analysis can be understood as an inductive thematic analysis (Clarke et al., 2015). The third step involved using supervised machine learning methods to validate the resultant qualitative themes. In this step, we used a variety of established natural language processing models to examine whether our final themes held across the dataset.

Our descriptive analysis included estimating the percentage of bots active in the tweet sample using Botometer Lite (Yang et al. 2020) and using the scraped hashtags in order to understand the likelihood of a micro-celebrity’s popularity within the community as opposed to being elevated by more obscure methods. Further, we examined patterns between political disinformation hashtags and COVID-19 related disinformation content. The governmental response to the coronavirus has changed American lives in dramatic ways, and thus we expected to see patterns emerge between the use of hashtags like #VoteDownBallot, #ProjectTakeOver, #FBA, #DrUmarJohnson, #blexit/#blaxit, and #covid19; the lack of any such connections was the basis for one part of the content analysis.

However, tweets pulled through either scraping or through the Twitter API are neither exhaustive nor a random sample, meaning that any relative frequencies within tweets pulled from either approach do not generalize to Twitter as a whole (Morstatter et al., 2013). Through a collaboration with MoveOn, we were able to access the Twitter firehose (a pipeline of 100% of all public Tweets; Gaffney & Puschmann, 2014) through a third-party social media intelligence and analysis company. This gives accurate frequency counts, from which we were able to compare frequencies of tweets to real-world events. Unfortunately, neither this set of tweets nor the daily time series generated from them can be shared due to the third-party terms of service, and could only be reproduced via firehose access.

We also note, however, that the firehose only provides tweets that still exist at the time of the query; tweets that have been removed since their posting (either deleted by the user or sent from an account that was suspended) will not appear in the daily counts. In a separate analysis, we estimate that 17% of the volume of #ADOS tweets were removed.4Estimate is based on daily counts from February 2019 to July 2019 queried in October 2020, and regressed via a Poisson model on daily counts for the same period, queried in July 2019. However, we do not know the nature of these removals, nor how this compares to Twitter overall.

This paper focused on analysis but was part of a larger, multi-modal intervention seeking to actively combat disinformation targeting Black voters on Twitter (MoveOn, 2020). While fully describing the design, execution, and outcomes of the counter-messaging is a task for future work, we want to acknowledge that this analysis is not a stand-alone piece of research and connects to practice. The intervention consisted of recruiting Philadelphia-based media makers and activists with significant social media followings, and supporting them in creating and disseminating anti-voter suppression messaging both online and offline. Messaging and content were mobilized under the hashtag #VoteDownCOVID, a campaign that Avila (2020) called an example of a “community-based solution” to fighting online propaganda.

Topics

Bibliography

Aceves, W. (2019). Virtual hatred: How Russia tried to start a race war in the United States. Michigan Journal of Race and Law, 24, 117–250. https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1290&context=mjrl

Adjei-Kontoh, H. (2019, November 21). The tortured logic of #ADOS. The Outline. https://theoutline.com/post/8286/american-descendants-of-slavery-movement

Aiwuyor, J. A. M. (2020, January 2). Understanding ADOS: The movement to hijack Black identity and weaken Black unity in America. IBW21. https://ibw21.org/commentary/understanding-ados-movement-hijack-black-identity-weaken-black-unity/

Alba, D. (2020, March 29). How Russia’s troll farm is changing tactics before the fall election. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/29/technology/russia-troll-farm-election.html

Albright, C. (2017, November 1). A Russian Facebook page organized a protest in Texas. A different Russian page launched the counter protest. The Texas Tribune. https://www.texastribune.org/2017/11/01/russian-facebook-page-organized-protest-texas-different-russian-page-l/

Avila, R. (2020, November 6). Fighting racism and hate speech with community solutions. DW Akademie. https://www.dw.com/en/fighting-racism-and-hate-speech-with-community-solutions/a-55522082

Bail, C. A., Argyle, L. P., Brown, T. W., Bumpus, J. P., Chen, H., Fallin Hunzaker, M. B., Lee, J., Mann, M., Merhout, F., & Volfovsky, A. (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences for America, 115(37), 9216–9221. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804840115

Bazelon, E. (2020, October 13). Free speech will save our democracy: The First Amendment in the age of disinformation. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/13/magazine/free-speech.html

Boehlert, E. (2019, April 17). Anti-immigrant activists are reportedly trying to get liberal radio host Mark Thompson fired. Daily Kos. https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2019/4/17/1850999/-Anti-immigrant-activists-are-reportedly-trying-to-get-liberal-radio-host-Mark-Thompson-fired

Brown, A. (2020, August 17). ADOS reparations movement co-founder Yvette Carnell goes primetime on CNN. The Moguldom Nation. https://moguldom.com/297515/ados-reparations-movement-co-founder-yvette-carnell-goes-primetime-on-cnn/

Brown, A., Houser, R. F., Mattei, J., Mozaffarian, D., Lichtenstein, A. H., & Folta, S. C. (2017). Hypertension among US-born and foreign-born non-Hispanic Blacks: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2014 data. Journal of Hypertension, 35(12), 2380–2387. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001489

Bump, P. (2016, December 14). 1.7 million people in 33 states and D.C. cast a ballot without voting in the presidential race. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/12/14/1-7-million-people-in-33-states-and-dc-cast-a-ballot-without-voting-in-the-presidential-race/

Carnell, Y. (2019, December 18). Democrats giving up on the Black vote? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQzSi06vGdU

Channel Four News Investigations Team. (2020, September 28). Revealed: Trump campaign strategy to deter millions of Black Americans from voting in 2016. Channel 4. https://www.channel4.com/news/revealed-trump-campaign-strategy-to-deter-millions-of-black-americans-from-voting-in-2016

Chavéz, A. (2019, February 13). Black critics of Kamala Harris and Cory Booker push back against claims that they’re Russian “bots.” The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2019/02/13/ados-kamala-harris-cory-booker-russian-bots/

Clarke, V., Braun, V., & Hayfield, N. (2015). Thematic analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed)., Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (3rd ed., pp. 222–248). SAGE Publications.

Crawford, B. (2020, May 27). ADOS: Its origins, troublesome ties and fears it’s dividing Black folk in the fight for reparations. The Final Call. https://www.finalcall.com/artman/publish/National_News_2/ADOS-Its-origins-troublesome-ties-and-fears-it-s-dividing-Black-folk-in-the-fight-for-reparations.shtml

Darity, W. A., Jr., & Mullen, K. A. (2020). From here to equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the twenty-first century. UNC Press.

Dinco, J. (2020, September 28). Downloading historical tweets using tweet_ids via snscrape and tweepy. Medium. https://medium.com/@jcldinco/downloading-historical-tweets-using-tweet-ids-via-snscrape-and-tweepy-5f4ecbf19032

Doamekpor, L. A., & Dinwiddie, G. Y. (2015). Allostatic load in foreign-born and US-born blacks: Evidence from the 2001-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 105(3), 591–597. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302285

Ellik, A. & Westbrook, A. (2018, November 28). Operation Infektion: Russian disinformation from the Cold War to Kanye. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/12/opinion/russia-meddling-disinformation-fake-news-elections.html

Freelon, D., Lopez, L., Clark, M. D., Jackson, S. J. (2018). How Black Twitter and other social media communities interact with mainstream news. Knight Foundation. https://knightfoundation.org/features/twittermedia/

Gaffney, D., & Puschmann, C. (2014). Data collection on Twitter. In K. Weller, A. Bruns, J. Burgess, M. Mahrt, & C. Puschmann, Twitter and Society (pp. 55–68). Peter Lang.

Gould, E. & Wilson, V. (2020, June 1). Black workers face two of the most lethal preexisting conditions for coronavirus—racism and economic inequality. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/black-workers-covid/

Graham, D. (2018, December 17). Russian trolls and the Trump campaign both tried to depress Black turnout. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/12/shared-russia-trump-focus-depressing-black-votes/578302/

Harvey, H. M. (2016, December 19). Skeptical 70,000 black voters abstained from presidential vote. The Hill. https://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/national-party-news/311099-skeptical-70000-black-voters-abstained-from

Hetrick, C. (2020, March 20). The Supreme Court sides with Comcast in Byron Allen’s racial discrimination case. The Philadelphia Inquirer. https://www.inquirer.com/business/comcast/supreme-court-comcast-byron-allen-racial-discrimination-case-20200323.html

Iheduru, A. (2013). Examining the social distance between Africans and African Americans: The role of internalized racism(Publication No. wsupsych1341565205) [Doctoral dissertation, Wright State University]. OhioLINK. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=wsupsych1341565205

Iofee, J. (2017, October 21). The history of Russian involvement in America’s Race Wars: From propaganda posters to Facebook ads, 80-plus years of Russian meddling. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/10/russia-facebook-race/542796/

Kearney, M. W. (2019). rtweet: Collecting and analyzing Twitter data. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(42), 1829. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01829

Khazanchi, R., Evans, C. T., & Marcelin, J. R. (2020, September 25). Racism, not race, drives inequity across the COVID-19 continuum. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2019933. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19933

Klein, R. (2018, August 12). Trump said ‘blame on both sides’ in Charlottesville, now the anniversary puts him on the spot. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/trump-blame-sides-charlottesville-now-anniversary-puts-spot/story?id=57141612

Lewis, S. (2020, August 30). Tributes pour in as celebrities and fans mourn the death of actor Chadwick Boseman. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/chadwick-boseman-dead-black-panther-tributes-celebrities-fans-mourn/

Luu, C. (2020, February 12). Black English matters. Jstor Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/black-english-matters/

Lynn, S. (2020, January 19). Controversial group ADOS divides black Americans in fight for economic equality. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/controversial-group-ados-divides-black-americans-fight-economic/story?id=66832680

Martin, R. S. (2020, October 15). Did Ice Cube really partner with Trump on ‘Platinum Plan’ for Black Americans? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eah23klP9Dg

McClintock P. (2018, March 24). Box office: ‘Black Panther’ becomes top-grossing superhero film of all time in U.S. The Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/heat-vision/box-office-black-panther-becomes-top-grossing-superhero-film-all-time-us-1097101

Mottl, D. (2019). GetOldTweets3. PYPI. https://pypi.org/project/GetOldTweets3/

Morstatter, F., Pfeffer, J. Liu, H., & Carley, K. (2013). Is the sample good enough? Comparing data from Twitter’s Streaming API with Twitter’s Firehose. Proceedings of the Seventh International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM-2013), 400–408. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14401

MoveOn. (2020). MoveOn 2020 election accomplishments. https://campaigns.moveon.org/2020-election-report/protect/

Mueller, R. S., Helderman, R. S., Zapotosky, M., & United States. (2019). Report on the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gov/storage/report.pdf

N’COBRA. (2020, March 14). N’COBRA to #ADOS and to those responding to #ADOS. N’COBRA: National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America. https://www.ncobraonline.org/ncobra-to-ados-and-those-responding-to-ados/

Nelson, L. K. (2020). Computational grounded theory: A methodological framework. Sociological Methods & Research, 49(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124117729703

Owens C. (2020). Blackout: How Black American can make its second escape from the Democratic plantation. Simon & Schuster.

Nkonde, M., Rodriguez, M. Y., Serrato, R., & Malik, M. M. (2021). Replication Data for “Disinformation creep: ADOS and the strategic weaponization of breaking news” [Data set]. Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FFLQUK

Nsangou, A., & Dundes, L. (2018). Parsing the gulf between Africans and African Americans. Social Sciences, 7(2), 24–50. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7020024

Parker, K., Horowitz, J. M., & Anderson, M. (2020, June 12). Amid protests, majorities across racial and ethnic groups express support for the Black Lives Matter Movement. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/06/12/amid-protests-majorities-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-express-support-for-the-black-lives-matter-movement/

Qui, L. (2017, December 12). Fingerprints of Russian disinformation: From AIDS to fake news. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/12/us/politics/russian-disinformation-aids-fake-news.html

Richardson, E. T., Malik, M. M., Darity, W. A., Jr., Mullen, A. K., Malik, M., Benton, A., Bassett, M. T., Farmer, P. E., Worden, L., & Jones, J. H. (2020). Reparations for Black American descendants of persons enslaved in the U.S. and their estimated impact on SARS-CoV-2 transmission. medRxiv 2020.06.04.20112011. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.04.20112011

Rid, T. (2020). Active measures: The secret history of disinformation and political warfare. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Roberts, M.E., Stewart, B.M., & Tingley, D. (2019). stm: An R package for Structural Topic Models. Journal of Statistical Software, 91(2), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v091.i02

Rodriguez, M. Y., & Storer, H. (2020). A computational social science perspective on qualitative data exploration: Using topic models for the descriptive analysis of social media data. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 38(1), 54–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2019.1616350

Russ, V. (2019, October 28). New Jersey NAACP chapter cancels screening of ‘Harriet,’ citing Comcast’s challenge to civil rights act. The Philadelphia Inquirer. https://www.inquirer.com/news/new-jersey/harriet-movie-naacp-comcast-civil-rights-law-1866-cancels-screening-new-jersey-20191028.html

Russian Intervention in European Elections: Hearing before the Select Committee on Intelligence of the United States Senate, 105th Cong. 1 (2017) (statement of Janis Sarts). https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/hearings/S.%20Hrg.%20115-105.pdf

SOVAW. (2018, October 11). Facebook ads that targeted voters centered on Black American culture with voter suppression as the end game. Stop Online Violence Against Women. http://stoponlinevaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Black-ID-Target-by-Russia-Report-SOVAW.pdf

SOVAW. (2020, January 7). A threat to an American democracy: Digital voter suppression, a key influence in the 2020 elections. Stop Online Violence Against Women. http://stoponlinevaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/7.pdf

Stanton, M. (2019). Red Black White: The Alabama Communist Party 1930–1950. University of Georgia Press.

Stockman, F. (2019a, November 8). ‘We’re self-interested’: The growing identity debate in Black America. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/08/us/slavery-black-immigrants-ados.html

Stockman, F. (2019b, November 13). Deciphering ADOS: A new social movement or online trolls? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/13/reader-center/slavery-descendants-ados.html

Stolberg, S. G. (2019, June 19). At historic hearing, House panel explores reparations. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/19/us/politics/slavery-reparations-hearing.html

Swan, B. W. (2020, April 21). State report: Russian, Chinese and Iranian disinformation narratives echo one another. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/04/21/russia-china-iran-disinformation-coronavirus-state-department-193107

Telusma, B. (2019, July 25). British actress Cynthia Erivo faces ‘Harriet’ backlash due to past tweets mocking Black Americans. The Grio. https://thegrio.com/2019/07/25/british-actress-cynthia-erivo-faces-harriet-backlash-due-to-past-tweets-mocking-black-americans/

Twitter. (2020, March 10). Developer agreement and policy. https://developer.twitter.com/en/developer-terms/agreement-and-policy

U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. (2019). Report of the Select Committee on Intelligence. Russian active measures campaigns and interference in the 2016 U.S. election, Volume 2: Russia’s use of social media with additional views(Report 116-XX). United States Senate. https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report_Volume2.pdf

Ward, C., Polglase, K., Shukla, S., Mezzofiore, G. & Lister, T. (2020, March 13). Russian meddling is back – via Ghana. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/12/world/russia-ghana-troll-farms-2020-ward/index.html

Watts, M. (2020, October 19). DL Hughley shares articles critical of Ice Cube and starts a Twitter beef. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/dl-hughley-shares-articles-critical-ice-cube-starts-twitter-beef-1540292

White, I. K. & Laird, C. N. (2020, February 25). Why are Blacks Democrats? Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/ideas/why-are-blacks-democrats

Winsor, M. (2016, June 13). Black Lives Matter protests go global, from Ireland to South Africa. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/International/black-lives-matter-protests-global-ireland-south-africa/story?id=40546549

Yang, K.-C., Varol, O., Hui, P.-M., & Menczer, F. (2020). Scalable and generalizable social bot detection through data selection. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 34(01), 1096–1103. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v34i01.5460

Funding

This research was not specifically commissioned or funded. MN, SK, and JKM would like to acknowledge the Philadelphia COVID-19 Community Information Fund, from the Lenfest Institute for Journalism, for a general operating grant which provided for salaries at the time of writing. MYR and the caretLAB at the School of Social Work, University at Buffalo also recognize support from this fund in supporting her contributions to this paper. LC did this work while receiving a graduate stipend from the Tisch School of the Arts, New York University, and again was not funded specifically for this work.

RS, NM, MD, AL, and MMM received salaries from MoveOn, a nonprofit and political action committee. While none of the funding that contributed to these salaries allocated specifically for this research or project, MoveOn voluntarily discloses every contributor to MoveOn.org Civic Action who gives gifts totaling $5,000 or more in any year. They would like to thank the numerous contributors to MoveOn who made this work possible, as well as thank MoveOn for its flexibility in allowing staff to contribute to an academic project in support of on-the-ground practitioners. MoveOn also provided a re-grant to MN, SK, and JKM, although this was for the intervention described at the end of the paper and not for the research described here, which happened prior to the intervention. Additional work was done by MMM in an independent capacity, without funding, after leaving MoveOn.

Competing Interests

MoveOn, a progressive public policy advocacy group and political action committee that supported the 2020 Democratic presidential campaign and engaged in Get-Out-the-Vote messaging for Black and other minority populations, assisted with data collection and management. Relevant MoveOn staff members share co-authorship credit. There are no other competing interests.

Ethics

The data for the project were obtained from publicly available online sources and thus were exempt from IRB review. Beyond what is governed by the IRB, we considered the ethics of including attributed tweets; in all cases, as the tweets we include are of public figures and/or are attempting to engage in a mass conversation. Especially as these relate to threats to the civic participation of Black populations, we believed it appropriate to include the tweets.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

Per the third-party terms of service, data accessed through the Twitter firehose may not be shared. However, we have provided scripts for redoing the scrape whose results were the basis of all but the frequency analysis in this paper, a list of the status_ids of those tweets (as knowing a status_id makes a tweet easier to recover than with scraping), as well code for analysis, via the Harvard Dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/FFLQUK