Peer Reviewed

Digital literacy is associated with more discerning accuracy judgments but not sharing intentions

Article Metrics

39

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

It has been widely argued that social media users with low digital literacy—who lack fluency with basic technological concepts related to the internet—are more likely to fall for online misinformation, but surprisingly little research has examined this association empirically. In a large survey experiment involving true and false news posts about politics and COVID-19, we found that digital literacy is indeed an important predictor of the ability to tell truth from falsehood when judging headline accuracy. However, digital literacy is not a robust predictor of users’ intentions to share true versus false headlines. This observation resonates with recent observations of a substantial disconnect between accuracy judgments and sharing intentions. Furthermore, our results suggest that lack of digital literacy may be useful for identifying people with inaccurate beliefs, but not for identifying those who are more likely to spread misinformation online.

Research Questions

- How do social media users’ level of digital literacy relate to their ability to discern truth versus falsehood when assessing the accuracy of news posts, and when deciding what news to share?

- How does the strength of these associations with digital literacy compare to other constructs that have been previously associated with truth discernment, particularly analytic thinking and general procedural news knowledge?

- Do these relationships differ based on users’ political partisanship, or the topic (politics versus COVID-19) of the news headlines?

Essay Summary

- In surveys conducted in late 2020, American social media users (N = 1,341) were presented with a set of true and false news posts about politics or COVID-19 taken from social media. Participants were randomly assigned to either assess the accuracy of each headline or indicate their likelihood of sharing each headline in social media, as well as completing two measures of digital literacy along with analytic thinking (the tendency to stop and think versus going with one’s gut), procedural news knowledge, partisanship, and basic demographics.

- Both digital literacy measures were positively associated with the ability to tell true from false headlines when assessing accuracy (accuracy discernment), regardless of the user’s partisanship or whether the headlines were about politics or COVID-19. General news knowledge was a stronger predictor of accuracy discernment than digital literacy, and analytic thinking was similar in strength to digital literacy.

- Conversely, neither digital literacy measure was consistently associated with sharing discernment (difference in sharing intentions for true relative to false headlines, or fraction of shared headlines that are true).

- These results emphasize the previously documented disconnect between accuracy judgments and sharing intentions and suggest that while digital literacy is a useful predictor of people’s ability to tell truth from falsehood, this may not translate to predicting the quality of information people share online.

Implications

In recent years, there has been a great deal of concern about misinformation and “fake news,” with a particular focus on the role played by social media. One popular explanation of why some people fall for online misinformation is lack of digital literacy: If people cannot competently navigate through digital spaces, then they may be more likely to believe and share false content that they encounter online. Thus, people who are less digitally literate may play a particularly large role in the spread of misinformation on social media.

Despite the intuitive appeal of this argument, however, there is little evidence to date in support of it. For example, Jones-Jang et al. (2019) found in a representative sample of US adults that digital literacy—defined as self-reported recognition of internet-related terms, which has been shown to predict the ability to effectively find information online (Guess & Munger, 2020; Hargittai 2005)—did not, in fact, predict the ability to identify fake news stories. Neither did scales measuring the distinct attributes of news literacy or media literacy; while information literacy—the ability to identify verified and reliable information, search databases, and identify opinion statements—did predict greater ability to identify fake news stories. Guess et al. (2020) found that a brief intervention aimed at teaching people how to spot fake news significantly improved the ability to tell truth from falsehood, but not sharing intentions, in both American and Indian samples, and Epstein et al. (2021) found that an even briefer version of the same intervention improved the quality of COVID-19 news Americans indicated they would share online (although this improvement was no greater than the improvement from simply priming the concept of accuracy). Relatedly, McGrew et al. (2019), Breakstone et al. (2021), and Brodsky et al. (2021) found that much more extensive fact-checking training modules focused on lateral reading improved students’ assessments of source and information credibility. These interventions were focused more on media literacy than on digital skills per se; and similarly, Hameleers (2020) found that a media literacy intervention with no digital literacy component increased American and Dutch subjects’ ability to identify misinformation. Conversely, Badrinathan (2021) found no effect of an hour-long media literacy training of Indian subjects’ ability to tell truth from falsehood.

In this paper, we aim to shed further light on the relationship between digital literacy and susceptibility to misinformation using a survey of 1,341 Americans, quota-sampled to match the national distribution on age, gender, ethnicity, and geographic region. We examine the association between two different measures of digital literacy and two outcome measures, belief and sharing, for true versus false news about politics and COVID-19.

We examine belief and sharing separately, as recent work has documented a substantial disconnect between these outcomes: Accuracy judgments tend to be much more discerning than sharing intentions (Epstein et al. 2021; Pennycook et al., 2020; Pennycook et al., 2021). Evidence suggests that this disconnect is largely driven by people failing to attend to accuracy when thinking about what to share (for a review, see Pennycook & Rand, in press). As a result, even if people who are more digitally literate are better able to tell truth from falsehood, this may not translate into improved sharing discernment. If they fail to even consider whether a piece of news is accurate before deciding to share it, their higher ability to identify which news is accurate will be of little assistance.

With respect to digital literacy, the first measure we use follows the tradition of conceptualizing digital literacy as the possession of basic digital skills required to effectively find information online (e.g., Hargittai, 2005). To measure this form of digital literacy, we use a set of self-report questions about familiarity with internet-related terms and attitudes towards technology that Guess & Munger (2020) found to be most predictive of actual performance on online information retrieval tasks. The second digital literacy measure we use, adapted from Newman et al. (2018), focuses specifically on literacy about social media and asks subjects how social media platforms decide which news stories to show them. This measure seems particularly well-suited to the challenges of identifying susceptibility to fake news on social media: If people do not understand that there are no editorial standards for content shared on social media, or that journalists do not get news before it is posted, it seems likely that they would be less skeptical of low-quality social media news content when they encounter it.

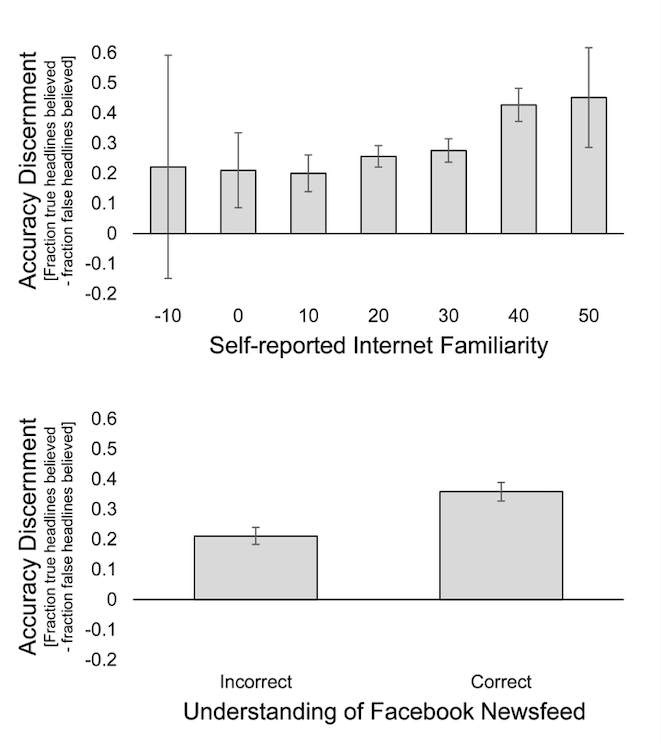

We find that both digital literacy measures are independently predictive of the tendency to rate true news as more accurate than false news—that is, of being able to successfully discern the truth of news (we define truth discernment as the average accuracy rating of true news minus the average accuracy ratings of false news). This positive association is similar in size to the association between truth discernment and both the tendency to engage in analytic thinking and performance on a procedural news knowledge quiz—measures which have been previously demonstrated to predict truth discernment (Amazeen & Bucy, 2019; Pennycook & Rand, 2019; Pennycook & Rand, 2021). The positive association between truth discernment and both digital literacy measures is equivalent for news about politics and COVID-19 and does not vary based on subjects’ partisanship. Thus, we find robust evidence that lack of digital literacy is indeed associated with less ability to tell truth from falsehood.

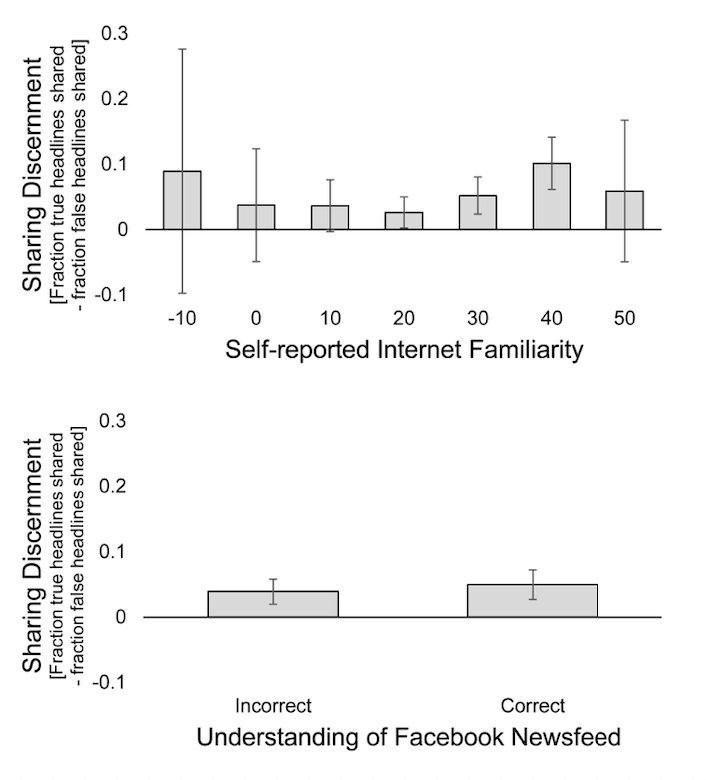

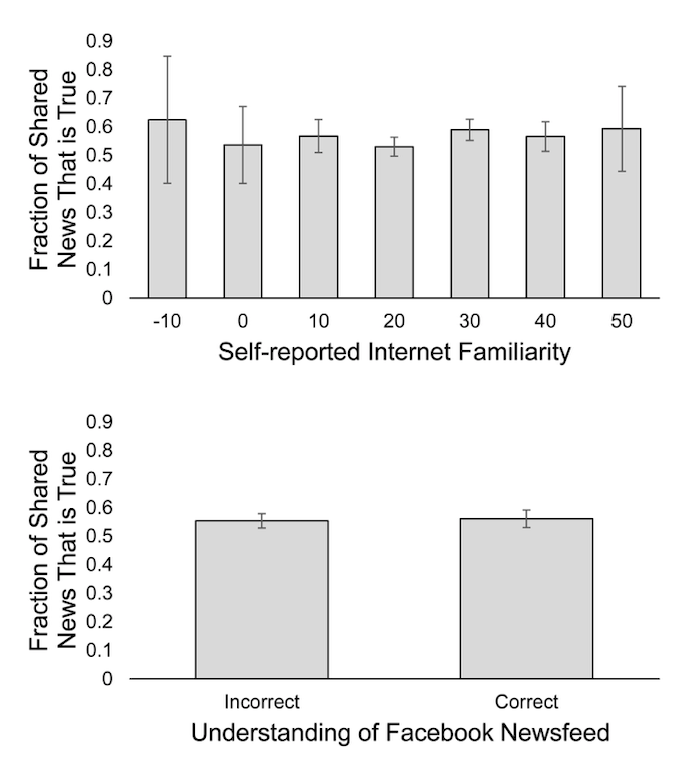

The pattern is strikingly different, however, when considering sharing intentions. Neither digital literacy measure is consistently associated with sharing discernment—the tendency to share true news more than false news—nor are they significantly associated with the fraction of headlines the subject shared that are true (an alternative metric of information sharing quality). Again, the results do not significantly differ for news about politics versus covid or based on participants’ partisanship. Analytic thinking is also not significantly associated with either sharing quality measure. It is only procedural news knowledge that is positively associated with having a higher fraction of shared content that is true (regardless of news type or partisanship) and positively associated with sharing discernment for Republicans.

These results add to the mixed pattern regarding digital literacy and misinformation on social media. While digital literacy was associated with a better ability to identify true versus false information, this did not appear to translate into sharing better quality information. Conversely, procedural news knowledge was positively predictive of both the ability to identify true versus false information and the tendency to share higher quality information. This is surprising, as one might intuitively have assumed that digital literacy was particularly relevant for social media sharing decisions. Yet, these findings resonate with experiments in which digital media literacy interventions increased belief accuracy but did not increase sharing discernment beyond simply priming the concept of accuracy (Epstein et al. 2021; Guess et al., 2020). And more generally, our digital literacy findings add to the growing body of evidence for a sizable disconnect between accuracy judgments and sharing intentions (e.g., Epstein et al. 2021; Pennycook et al., 2020; Pennycook et al., 2021). More digitally literate subjects’ higher accuracy discernment did not translate into higher sharing discernment, likely (at least in part) due to people’s tendency to fail to consider accuracy when considering what to share (Pennycook & Rand, in press).

An important implication of our findings is that digital literacy may be useful (e.g., for policymakers or social media platforms) when trying to identify users who are vulnerable to believing misinformation, but it does not seem particularly promising for identifying users who are likely to spread misinformation. Our findings also have implications regarding the potential impact of interventions that shift attention to accuracy to reduce the sharing of misinformation (for a review of the accuracy prompt approach, see Pennycook & Rand, in press). Although digital literacy did not significantly predict baseline sharing discernment, it seems likely that higher digital literacy users’ sharing decisions will be more responsive to accuracy prompts because their underlying accuracy judgments are better calibrated: Once their attention is shifted to accuracy, their improved accuracy discernment should then translate into improved sharing discernment. Testing this empirically is a promising direction for future study. Finally, if future work shows that the correlational relationships observed here reflect underlying causal effects, that could suggest that education interventions aimed at improving the quality of content shared online would do better to focus on procedural news knowledge more generally, rather than digital literacy per se.

On all these counts, it is essential for future work to explore cross-cultural generalizability. This is particularly true given that in many parts of the world, widespread access to digital technologies is an extremely recent development, and thus digital literacy levels are likely to be quite low. It is also of great importance to keep in mind that a major limitation of our study is that our sharing intention judgments are hypothetical. Although the hypothetical sharing intentions measure employed here has been widely used in the literature (e.g., Epstein et al. 2021; Guess et al., 2020; Pennycook & Rand, 2019; Pennycook et al., 2020; Pennycook et al., 2021; Roozenbeek et al., 2021; Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2020; Rosenzweig et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2021), it is of paramount importance for future work to examine the relationship between digital literacy and actual on-platform sharing.

Finally, our findings are also important for the ongoing discussion about what, exactly, digital literacy is (e.g., Guess & Munger, 2020). We examined measures capturing two distinct notions of digital literacy and found that each measure was similarly predictive of truth discernment, even when both were included in the same model, along with procedural news knowledge and general analytic thinking. This emphasizes the multifaceted nature of digital literacy and the importance of future scholarship further elucidating the many dimensions of digital literacy, as well as the relationship between digital literacy, media literacy, and digital media literacy.

Findings

Finding 1: More digitally literate social media users show better truth discernment.

We predict participants’ ability to tell true headlines from false headlines (truth discernment, defined as average accuracy ratings for true headlines minus average accurate ratings for false headlines) including controls for age, gender, race (white versus non-white), education (less than college degree versus college degree or more), political partisanship, and headline content (political versus COVID-19). We find a significant positive relationship for self-reported familiarity/comfort with the internet (β = .224, 95% CI = [0.154, 0.295], p < .001) and for correct understanding of the Facebook newsfeed algorithm (β = .231, 95% CI = [0.164, 0.297], p < .001); see Figure 1. The size of these relationships is similar to what we find for procedural news knowledge (β = .290, 95% CI = [0.221, 0.359], p < .001) and analytic thinking (β = .210, 95% CI = [0.142, 0.278], p < .001), replicating previous findings (e.g., Amazeen & Bucy, 2019; Pennycook & Rand, 2019; Pennycook & Rand, 2021).

Finding 2: More digitally literate social media users are no more discerning in their sharing.

We predict participants’ tendency to share true headlines more than false headlines (sharing discernment, defined as average sharing probability for true headlines minus average sharing probability for false headlines) including controls for age, gender, race, education, political partisanship, and headline content. We find no significant relationship for self-reported familiarity/comfort with the internet (β = .068, 95% CI = [-0.010, 0.146], p = .088) or for correct understanding of the Facebook newsfeed algorithm (β = .027, 95% CI = [-0.048, 0.101], p = .483); see Figure 2. We also find no significant relationship for procedural news knowledge (β = .051, 95% CI = [-0.027, 0.130], p = .199) or analytic thinking (β = -.019, 95% CI = [-0.094, 0.057], p = .628). The lack of association with analytic thinking is interesting as it stands in contrast to previous working findings that analytic thinking is positively associated with sharing discernment for political news (Ross et al., 2021) and COVID-19 news (Pennycook et al., 2020), and the quality of news sites shared on Twitter (Mosleh et al., 2021) (although, see Osmundsen et al., 2021 who do not find a significant relationship between analytic thinking and the sharing of fake news on Twitter).

This measure of sharing discernment, however, can be potentially misleading when comparing groups where the overall sharing rate differs substantially. Thus, as a robustness check, we also consider a different measure of sharing quality: out of all of the news that the user said they would share, what fraction is true? (That is, we divide the number of true headlines selected for sharing by the total number of headlines selected for sharing). We predict this fraction of the subject’s shared headlines that are true—again including controls for age, gender, race, education, political partisanship, and headline content—and continue to find no significant relationship for self-reported familiarity/comfort with the internet (β = .013, 95% CI = [-0.080, 0.106], p = .784) or for correct understanding of the Facebook newsfeed algorithm (β = .015, 95% CI = [-0.072, 0.102], p = .348); see Figure 3. We also find no significant relationship for analytic thinking (β = .002, 95% CI = [-0.093, 0.097], p = .961), but we do find a highly significant positive relationship for procedural news knowledge (β = 0.153, 95% CI = [0.057, 0.248], p = 0.002).

We note that these null results for digital literacy are not easily attributable to floor effects. First, the average sharing probabilities are far from the floor of 0: 36.4% of false headlines and 40.3% of true headlines were shared (yielding an average discernment of 0.403-0.364 = 0.039). Second, we find that other factors were significantly related to sharing discernment, indicating that there is enough signal to observe relationships that do exist. Furthermore, our results are broadly consistent when excluding users who, at the outset of the study, indicated that they would never share anything on social media, or who indicated that they did not share political news on social media. The only exception is that self-reported internet familiarity was significantly positively related with the first sharing discernment measure (β = .18, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.30], p = 0.002) when excluding users who stated that they never share political news. Given that this was the only significant result out of the numerous combinations of digital literacy measure, sharing outcome measure, and exclusion criteria, we conclude that there is no robust evidence that digital literacy is associated with the quality of sharing intentions.

Finding 3: Relationships between digital literacy and discernment are similar for Democrats and Republicans, and for news about politics and COVID-19.

Finally, we ask whether there is evidence that the results discussed above differ significantly based on the subject’s partisanship or the focus of the headlines being judged. To do so, we use a model including both digital literacy measures, procedural news knowledge, analytic thinking, and all controls, and interact each of these variables with partisanship (6-point scale of preference for Democrat versus Republican party) and headline content (political versus COVID-19), as well as including the relevant three-way interactions. We find no significant two-way or three-way interactions for either digital literacy measure when predicting truth discernment or either sharing discernment measure (p > .05 for all). Thus, we do not find evidence that the relationship (or lack thereof) between digital literacy and discernment varies based on user partisanship or political versus COVID-19 news.

Conversely, we do find some significant interactions for analytic thinking and procedural news knowledge (although these interactions should be interpreted with caution given the lack of ex ante predictions and the large number of tests performed). When predicting truth discernment we find a significant three-way interaction between analytic thinking, partisanship, and news type (β = .095, 95% CI = [0.030, 0.161], p = .005), such that when judging political news analytic thinking positively predicts truth discernment regardless of user partisanship, but when judging COVID-19 news analytic thinking only predicts greater truth discernment for Democrats but not Republicans. This pattern differs from what has been observed previously, where participants higher on analytic thinking were more discerning regardless of partisanship for both political news (e.g., Pennycook & Rand, 2019) and COVID-19 news (e.g., re-analysis of data from Pennycook et al., 2020). When predicting sharing discernment, we find a significant two-way interaction between procedural news knowledge and partisanship (β = .133, 95% CI = [0.043, 0.223], p = .004), such that procedural news knowledge is associated with significantly greater sharing discernment for Republicans but not for Democrats. We also find a significant three-way interaction between analytic thinking, partisanship, and news type (β = .095, 95% CI = [0.030, 0.161], p = .005), but the association between analytic thinking and sharing discernment is not significantly different from zero for any subgroup. Finally, when predicting the fraction of shared headlines that are true, we find a significant two-way interaction between analytic thinking and politics (β = .111, 95% CI = [0.009, 0.213], p = .033), such that analytic thinking is associated with a significantly lower fraction of true headlines shared for COVID-19 news but not political news.

Methods

We conducted two waves of data collection with two similarly structured surveys on Qualtrics. Our final dataset included a total of 1,341 individuals: mean age = 44.7, 59.3% female, 72.4% White. These users were recruited on Lucid, which uses quota-sampling in an effort to match the national distribution of age, gender, ethnicity, and geographic region. Participants were first asked “What type of social media accounts do you use (if any)?” and only participants who had selected Facebook and/or Twitter were allowed to participate. The studies were exempted by MIT COUHES (protocol 1806400195).

In both surveys, participants were shown a series of news items, some of which were true and others which were false. The first wave had 25 headlines (just text) pertaining to COVID-19, 15 false and 10 true, and participants saw all 25. This study (N = 349) was conducted from July 29, 2020 to August 8, 2020. The second wave (N = 992) had 60 online news cards about politics (including headline, image, and source), half were true and half false, and subjects were shown a random subset of 24 of these headlines. This study was conducted from October 3, 2020 to October 11, 2020. Full experimental materials are available at https://osf.io/kyx9z/?view_only=762302214a8248789bc6aeaa1c209029.

Each subject was randomly assigned to one of two conditions for all headlines: accuracy and sharing. In the accuracy condition, participants were asked for each headline “To the best of your knowledge, is the claim in the above headline accurate?” In the sharing condition, they were instead asked “Would you consider sharing this story online (for example, through Facebook or Twitter)?” Both questions had binary no/yes response options. In the political item wave, participants in the sharing condition were also asked if they would like or comment on each headline, but we do not analyze those responses here because they were not included in the COVID-19 wave. Both experiments also included two additional treatment conditions (in which both accuracy and sharing were asked together) that we do not analyze here, as prior work has shown that asking the accuracy and sharing together dramatically changes responses (e.g., Pennycook et al., 2021), and thus these data do not provide clean measures of accuracy discernment and sharing discernment.

Given the survey nature of our experiment, we were limited to measuring people’s intentions to share social media posts, rather than actual sharing on platforms. This is an important limitation, although some reason to expect the relationships observed here to extend to actual sharing comes from the observation that self-reported willingness to share a given article is meaningfully correlated with the number of shares of that article actually received on Twitter (Mosleh et al., 2020; although this study examined item-level, rather than subject-level, correlations), and from the observation that an intervention (accuracy prompts) that was developed using sharing intentions as the outcome was successful when deployed on actual sharing in a field experiment on Twitter (Pennycook et al., 2021); this suggests that the sharing intentions were not just noise but contained meaningful signal as to what people would actually share (and how that sharing would respond to the intervention).

Following the main task, participants completed a question about their knowledge of the Facebook algorithm (Newman et al., 2018) that asked, “How are the decisions about what stories to show people on Facebook made?” The answer choices were At Random; By editors and journalists that work for news outlets; By editors and journalists that work for Facebook; By computer analysis of what stories might interest you; and I don’t know. If the participant selected I don’t know, they were asked to give their best guess out of the remaining choices in a follow-up question. Participants who chose By computer analysis of what stories might interest you in either stage were scored as responding correctly. Next, they completed a short form of the digital literacy battery from Guess & Munger (2020), responding to “How familiar are you with the following computer and Internet-related items?” using a slider scale from 1 (no understanding) to 5 (full understanding) for phishing, hashtags, JPEG, malware, cache, and RSS; and indicated their agreement with four statements about attitudes towards digital technology using a scale of -4 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree): I prefer to ask friends how to use any new technological gadget instead of trying to figure it out myself; I feel like information technology is a part of my daily life; Using information technology makes it easier to do my work; and I often have trouble finding things that I’ve saved on my computer. Finally, participants completed a three-item cognitive reflection test that measures analytic thinking using math problems that have intuitively compelling but incorrect answers (Frederick, 2005), a ten-item procedural news knowledge quiz adapted from Amazeen & Busy (2019), and demographics. Table 1 shows the pairwise correlations between the various individual difference measures.

| Self-report Internet Familiarity | Understanding of FB Newsfeed | Procedural News Knowledge | Cognitive Reflection Test | Age | Education | Gender | Race | Preference for Republican Party | |

| Self-report Internet Familiarity | 1 | ||||||||

| Understanding of FB Newsfeed | 0.206* | 1 | |||||||

| Procedural News Knowledge | 0.095* | 0.262* | 1 | ||||||

| Cognitive Reflection Test | 0.115* | 0.184* | 0.262* | 1 | |||||

| Age | -0.162* | -0.026 | 0.327* | 0.063 | 1 | ||||

| Education (1 = college degree) | 0.192* | 0.136* | 0.056 | 0.163* | 0.016 | 1 | |||

| Gender (1 = female) | -0.198* | 0.022 | 0.055 | -0.135* | 0.137* | -0.204* | 1 | ||

| Race (1 = White) | 0.019 | 0.072 | 0.150* | 0.042 | 0.255* | 0.093* | -0.036 | 1 | |

| Preference for Republican Party | -0.015 | -0.028 | -0.069 | 0.037 | 0.128* | 0.000 | -0.044 | 0.215* | 1 |

Topics

Bibliography

Amazeen, M. A., & Bucy, E. P. (2019). Conferring resistance to digital disinformation: The inoculating influence of procedural news knowledge. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 63(3), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2019.1653101

Badrinathan, S. (2021). Educative interventions to combat misinformation: Evidence from a field experiment in India. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1325–1341. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000459

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Connors, P., Ortega, T., Kerr, D., & Wineburg, S. (2021). Lateral reading: College students learn to critically evaluate internet sources in an online course. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-56

Brodsky, J. E., Brooks, P. J., Scimeca, D., Todorova, R., Galati, P., Batson, M., Grosso, R., Matthews, M., Miller, V., & Caulfield, M. (2021). Improving college students’ fact-checking strategies through lateral reading instruction in a general education civics course. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6(23). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00291-4

Epstein, Z., Berinsky, A. J., Cole, R., Gully, A., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Developing an accuracy-prompt toolkit to reduce Covid-19 misinformation online. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-71

Frederick, S., (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 25–42. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/089533005775196732

Guess, A. M., Lerner, M., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., & Sircar, N. (2020). A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and false news in the United States and India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(27), 15536–15545. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920498117

Guess, A., & Munger, K. (2020). Digital literacy and online political behavior. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3ncmk

Hameleers, M. (2020). Separating truth from lies: Comparing the effects of news media literacy interventions and fact-checkers in response to political misinformation in the US and Netherlands. Information, Communication & Society. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1764603

Hargittai, E. (2005). Survey measures of web-oriented digital literacy. Social Science Computer Review, 23(3), 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439305275911

McGrew, S., Smith, M., Breakstone, J., Ortega, T., & Wineburg, S. (2019). Improving university students’ web savvy: An intervention study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12279

Mosleh, M., Pennycook, G., Arechar, A. A., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Cognitive reflection correlates with behavior on Twitter. Nature Communications, 12(921). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20043-0

Mosleh, M., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Self-reported willingness to share political news articles in online surveys correlates with actual sharing on Twitter. PLOS One, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228882

Mortensen, T., Jones-Jang, S. M., & Liu, J. (2019). Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869406

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. A. L., & Nielsen, R. K. (2018). Reuters Institute digital news report 2018. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/media.digitalnewsreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/digital-news-report-2018.pdf

Osmundsen, M., Bor, A., Vahlstrup, P., Bechmann, A., & Petersen, M. (2021). Partisan polarization is the primary psychological motivation behind political fake news sharing on Twitter. American Political Science Review, 115(3), 999–1015. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000290

Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar A. A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature, 592, 590–595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03344-2

Pennycook, G., McPhetres, J., Zhang, Y., Jackson, L. G., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychological Science, 31(7), 770–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620939054

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition, 188, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.011

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 25(5), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (in press). Nudging social media sharing towards accuracy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/tp6vy

Roozenbeek, J., Freeman, A. L. J., & van der Linden, S. (2021). How accurate are accuracy-nudge interventions? A preregistered direct replication of Pennycook et al. (2020). Psychological Science, 32(7), 1169 –1178. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211024535

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2020). Breaking Harmony Square: A game that “inoculates” against political misinformation. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(8). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-47

Rosenzweig, L. R., Bago, B., Berinsky A. J., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Happiness and surprise are associated with worse truth discernment of COVID-19 headlines among social media users in Nigeria. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-75

Ross, R. M., Rand, D. G., & Pennycook, G. (2021). Beyond “fake news”: Analytic thinking and the detection of false and hyperpartisan news headlines. Judgment and Decision Making, 16(2), 484–504. http://journal.sjdm.org/20/200616b/jdm200616b.pdf

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Initiative of the Miami Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Reset Initiative of Luminate (part of the Omidyar Network), the John Templeton Foundation, the TDF Foundation, and Google.

Competing Interests

DR received research support through gifts to MIT from Google and Facebook.

Ethics

This research was deemed exempt by the MIT Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects, # E-2443.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available at https://osf.io/kyx9z/?view_only=762302214a8248789bc6aeaa1c209029 and via the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/N0ITTI (data & code) and at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WG3P0Y (materials).