Peer Reviewed

Chinese state media Facebook ads are linked to changes in news coverage of China worldwide

Article Metrics

2

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

We studied the relationship between Facebook advertisements from Chinese state media on the global media environment by examining the link between advertisements and online news coverage of China by other countries. We found that countries that see a large increase in views of Facebook advertisement from Chinese state media also see news coverage of China become more positive. News coverage also becomes more likely to use keywords that suggest a point of view favorable to China. One possible explanation is that by drawing greater attention to the issues emphasized by Chinese state media, the advertisements help Chinese state media set the news agenda covered by other media sources.

Research Questions

- Is increased exposure to Chinese state media Facebook ads within a country associated with changes in the tone of news coverage of China?

- Is increased exposure to Chinese state media Facebook ads within a country associated with changes in the content of news coverage of China?

- Do the changes linked to exposure to Chinese state media ads decrease after Facebook’s adoption of labels indicating that an advertisement is from state-controlled media?

Essay Summary

- We analyzed the relationship between Chinese state media Facebook advertisements and coverage of China in news articles from around the world published between 2018 and 2020.

- We measured the number of times all Facebook advertisements from Chinese state media Facebook pages were shown on screens in over 100 countries from 2018 to 2020.

- We collected news articles about China published online in each country from 2018 to 2020, and found the average tone of the news articles became more favorable, and the number of articles containing keywords that suggested a stance favorable to China increased.

- We found that after countries were exposed to Chinese state media advertisements, news articles on China had a more positive tone, and were more likely to contain keywords suggesting a stance favorable to China.

- The link between impressions and the tone of coverage of China weakened after Facebook’s adoption of state-funding labels in June 2020.

- The findings suggest that social media platforms should take steps to limit the dissemination of state propaganda via paid advertisements, such as applying state-funding labels more consistently and prominently.

Implications

Much research has examined states’ use of social media to spread propaganda. Propaganda disseminated to foreign audiences via social media can shape public opinion (Carter & Carter, 2021; Nassetta & Gross, 2020) and spread misinformation on critical issues like COVID-19 (Molter & DiResta, 2020). The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), in particular, maintains an extensive outward-facing propaganda apparatus, centering around state media outlets that use social media, TV, radio, print, and online formats (Cook, 2020). Chinese state media uses tweets (Huang & Wang, 2020; Jia & Li, 2020) and Facebook posts and advertisements (Huang & Wang, 2020; Insikt Group, 2020; Molter & DiResta, 2020; Xiao, 2021) to promote official government positions to foreign audiences. This propaganda apparatus has a significant social media following, with the China Global Television Network (CGTN), People’s Daily, and China Daily numbering among the most-liked pages on Facebook (Mantesso & Zhou, 2019).

Prior research has suggested that this propaganda apparatus may influence the global media environment, suppressing criticism of China and promoting CCP views on contentious issues (Cook, 2013; Cook, 2021; Custer et al., 2019). Surveys have demonstrated subjective assessments among journalists of growing Chinese influence in local media environments (Lim & Bergin, 2020), while others have identified examples of independent news outlets re-printing articles originally published by Chinese state media in Taiwan, Iran, Thailand, Italy, and the Philippines (Carrer, 2020; Chia, 2020; Cook, 2013; DiResta et al., 2020; Kurlantzick, 2020; Lim & Bergin, 2020). Chinese state media coverage was shown to drive changes in news coverage in the United States (Fu, 2013) and Kenya (Gooch et al., 2020). These analyses, however, focus on individual topics in just a handful of countries. It has also been shown that reporting from East Asian countries has become less critical of China (Custer et al., 2019), but no link has been established between this change and the activities of Chinese state media.

Our findings highlight the potential for Chinese government propaganda disseminated via social media to shape other countries’ media environments. We found that Facebook advertisements from Chinese state media are linked to changes in the tone and content of news reporting on China. We examined countries that saw a sharp increase in the number of times these Facebook advertisements were shown on screens. In the week following the increase in advertisements, the tone of news coverage of China became more positive, and the number of articles containing keywords that suggest a stance favorable to China also increased.

China’s outward-facing propaganda is coordinated under the State Council Information Office (Brady, 2015). As is common for advertisers, their Facebook advertisements are coordinated with media content on other platforms. Advertisements often promote news articles from Chinese state media, typically one day after the article’s publication, or feature content identical to tweets or YouTube videos from Chinese state media. Due to this coordination, our data may describe the collective reach of China’s cross-platform media activities, rather than the reach of Facebook advertising alone.

The intermedia agenda-setting literature suggests a possible causal interpretation of our findings: Chinese state media activity can play an agenda-setting role, increasing audience attention to particular issues, driving local news outlets to cover those issues (Protess & McCombs, 1991; Sweetser et al., 2008). Social media (Ferrucci, 2018; Su & Lee, 2020; Valenzuela et al., 2017; Vargo & Guo, 2016), and Facebook in particular (Feezell, 2017), has been shown to play an outsized agenda-setting role. Agenda-setting effects have also been demonstrated for news sources, including Chinese state media, that reach across national boundaries (Cheng et al., 2015; Golan, 2007; Lim, 2006;). Further research is required to identify the particular means by which agenda-setting occurs in our context (Vliegenthart & Walgrave, 2008). For example, do Facebook advertisements send a signal of newsworthiness to media organizations via audience engagement (Moy et al., 2016) or the news articles they promote (Dearing & Rogers, 1996; Weaver et al., 2005), or do Facebook advertisements build audience demand for particular news stories (Mathes & Pfetsch, 1991; Lee et al., 2014)? The answers to these types of questions can inform which interventions may best counteract state propaganda.

Our work extends the intermedia agenda-setting literature in two ways. First, we are among the first to incorporate data on the viewership of media content, especially in a large-scale, cross-national context—an important dimension of agenda-setting effects. Second, the literature rarely studies the intersection of outward-facing propaganda and intermedia agenda-setting. Our findings suggest more attention is needed to how states may leverage agenda-setting effects to advance their goals.

In June 2020, Facebook began attaching state-funding labels to advertisements from state media, as shown in Figure 1 (Gleicher, 2020). Previous work has demonstrated that these labels reduce the effect of propaganda YouTube videos on viewers’ political opinions (Nassetta & Gross, 2020), while distinct misinformation labels on Facebook reduce the rate at which misleading posts are shared (Musil, 2020). Facebook’s state-funding labels have not yet been studied. We examine the change in coverage before and after Facebook’s labeling policy went into effect. After the adoption of labels, the link between Chinese state media advertisements and changes in news coverage becomes smaller.

Social media advertisements allow state propaganda to gain influence in foreign countries. Policymakers and platforms should limit this influence. First, several state media Facebook pages are missing state-funding labels, which represents a lingering problem for state-funding labels (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2020). Facebook also often allows Chinese state media advertisements to run for days without disclaimers before they are removed (Purnell, 2021). Facebook should ensure labels are applied to all state-funded pages, and advertisements violating the labeling policy must be removed more promptly. Policymakers should also enforce labeling requirements directly or adopt other means of curtailing the influence of state media advertisements, as others have suggested (Nott, 2020; Vandewalker, 2017). Alternatively, given that these ads, as Facebook itself has acknowledged, “combine the influence of a media organization with the backing of a state” (Gleicher, 2020) and distort the free flow of information (Bjola, 2017), platforms and policymakers should also consider prohibiting ad purchases from state media entirely, following Twitter (Twitter, Inc., 2019).

Findings

Finding 1: Chinese state media Facebook advertisements appear alongside content on other platforms and are shown on screens 655 million times.

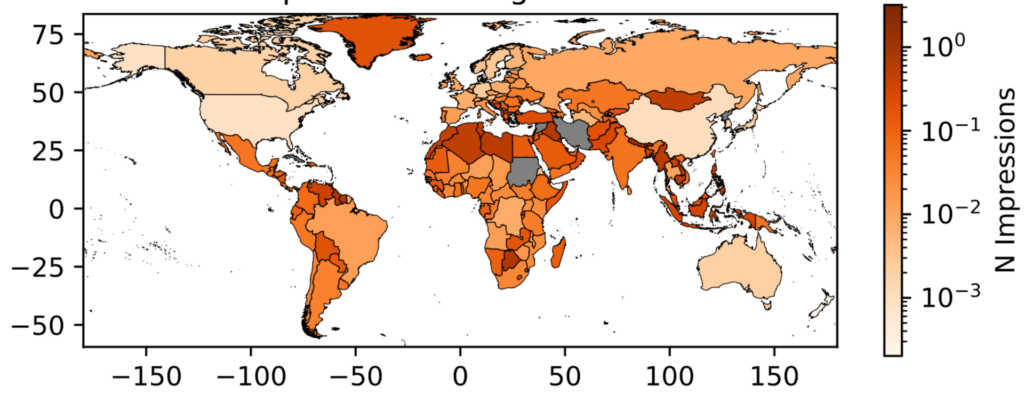

We collected the number of impressions, or the number of times Facebook advertisements posted by Chinese state media pages were shown on screens, in each country between 2018 and 2020. Collectively, the advertisements garnered 655 million impressions, with some countries targeted more heavily than others. Figure 2 shows the number of impressions in each country, divided by the country’s population to avoid overemphasizing populous countries.

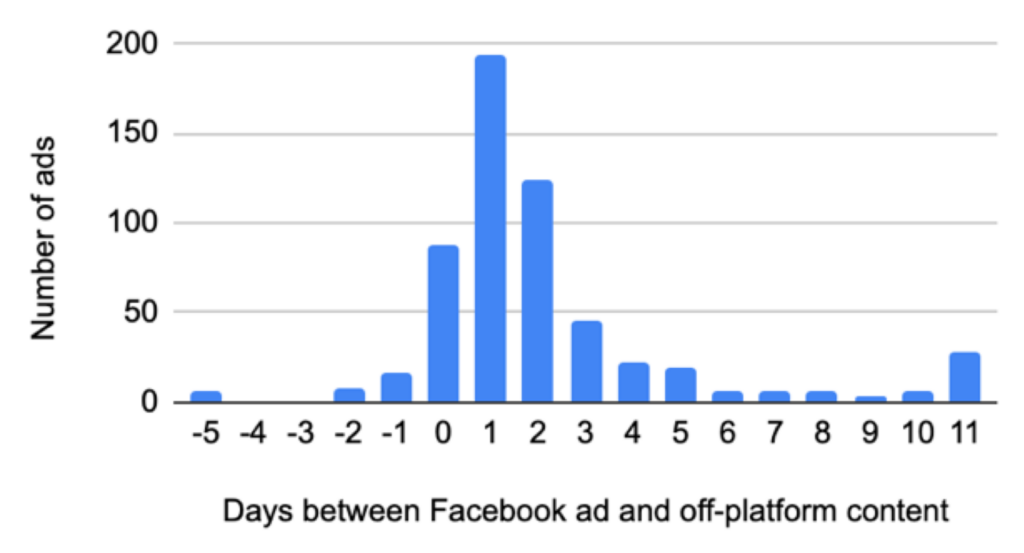

Facebook ads often appear in tandem with identical state media content on other platforms. 49% of advertisements appear alongside state media articles, and an additional 12% appear alongside state media content on YouTube, Twitter, or other platforms. Figure 3 shows when ads are posted relative to the corresponding cross-platform content. A value of 1 on the x-axis means the Facebook advertisement is posted one day after the cross-platform content. The y-axis shows the number of ads. 74% of the advertisements tied to cross-platform content were published within two days of (+/-) the content posting on other platforms.

Finding 2: Increased appearances of Chinese state media Facebook advertisements are associated with more positive reporting on China.

We collected news articles about China published online in each country from 2018 to 2020. We identified countries in which the number of impressions sharply rose over a ten-day period and evaluated how the tone of those news articles changed over the seven days after the rise in impressions.

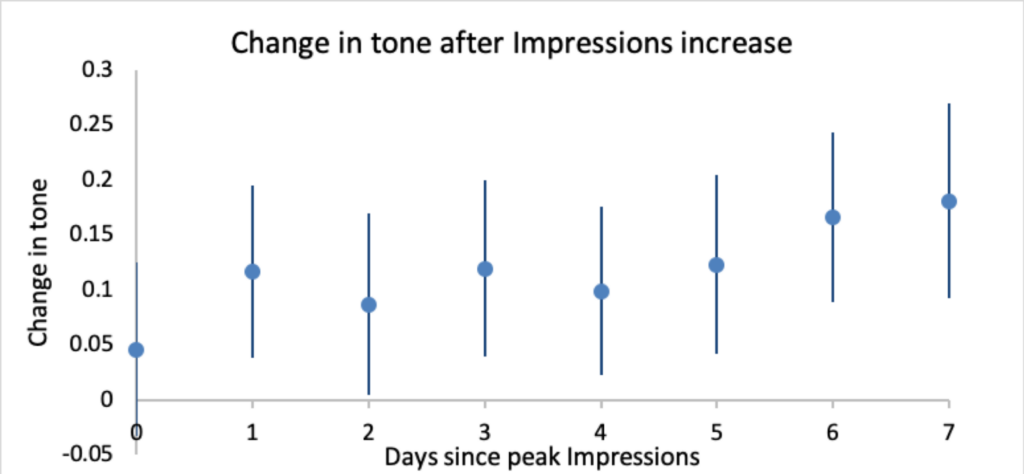

After users in a country were exposed to an increase in Chinese state media impressions, the average tone of news articles became substantially more positive. Figure 2 shows the average change in article tone after exposure to impressions, from zero to seven days after the increase in impressions. The size of the change ranges from roughly 0.08 to 0.18. The bars show 95% confidence intervals around each point, and indicate that all effects except for the effect on the day of the increase are statistically significant.

To contextualize the magnitude of the change, an article’s tone can range between 10 (extremely positive) and -10 (extremely negative), with 70% of articles ranging between -3 and +3. Figure 5 gives examples of articles with tone scores of -2, -1, and 0, from left to right. A change in tone of 0.1 would imply that 10% of articles would resemble the rightmost article instead of the middle one.

For further context, the average tone of articles about China saw a 1-point drop at the start of 2020, likely linked to the COVID-19 pandemic (Jacob, 2020; Reuters Staff, 2020). The standard deviation, representing the cumulative effect of various causes of fluctuation in coverage of China, is about 1.4. The effect of impressions exposure shown in Figure 4 is roughly one-twentieth to one-tenth of these sizes.

Finding 3: Increased appearance of Chinese state media Facebook advertisements is associated with an increase in the number of articles mentioning keywords suggestive of a pro-China point of view.

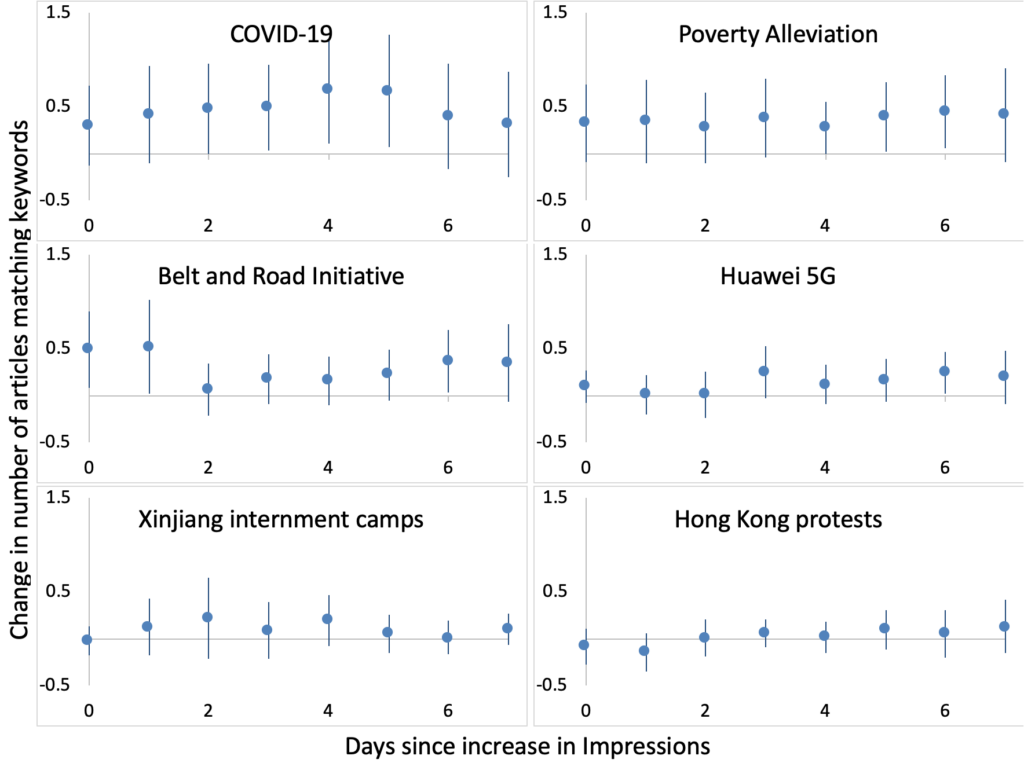

Given the change in the overall tone of coverage of China, we then assessed how coverage of China on particular issues may have changed. We selected six topics mentioned heavily in the Facebook advertisements and identified keywords that suggested a stance favorable to China for each topic. For instance, articles covering the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong using the term “riot” as opposed to the word “protest” are more likely to align with China’s point of view.

We found that an increase in Chinese state media impressions is associated with an increase in the number of articles containing keywords that suggest favorability to China. Figure 6 shows the change in the number of articles published that matches each set of keywords following the increase in impressions. After exposure to impressions, there is an increase in favorable coverage of COVID-19, China’s domestic poverty alleviation, the Belt and Road Initiative, and Huawei’s 5G network. Results for coverage of internment camps in Xinjiang and protests in Hong Kong did not reach statistical significance.

In these graphs, the y-axis denotes the number of news articles published in the days following exposure to impressions. An effect size of 0.5 would thus imply that one additional article matching the keywords was published in half of the instances in which a country is exposed to impressions. The results suggest that for some topic areas, the presence of Facebook advertisements is linked to an increase in the volume of news coverage on various issues that may be partial to the Chinese government’s official position.

Finding 4: When advertisements have state-funding labels, the change in article tone associated with the advertisements is smaller.

Facebook adopted state-funding labels on June 4, 2020. To assess the efficacy of the labels, we considered how the effect of exposure to impressions changes before and after this policy change. We collected the changes in tone associated with exposure to impressions (i.e., the results from our first experiment) over time. However, the direct comparison between the changes in tone before versus after the adoption of state-funding labels suffers from confounding: any change occurring around June 4 that affects the influence of Chinese state media Facebook advertisements—for instance, a change in Facebook’s news feed algorithm—could be responsible for this change instead of the labels.

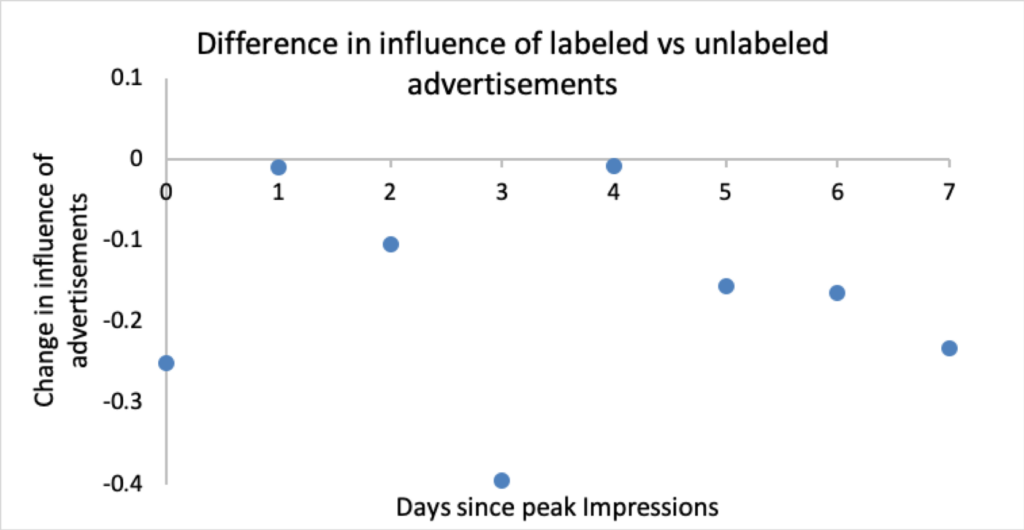

Conveniently for the purposes of this study, some state-produced advertisements never had state-funding labels at any time (before or after June 4) due to erroneous labeling practices by Facebook. We used this group of unlabeled advertisements as a control to correct for confounding from underlying trends in the changes in tone. Figure 7 reports the difference between the average change in tone before versus after adoption of state-funding labels.

Each point indicates the difference in the size of the changes linked to state-funded advertisements with labels and without labels for zero through seven days after exposure to the advertisements. Negative values indicate that the changes linked to advertisements that have state-funding labels are smaller than the changes linked to advertisements without the labels. Figure 7 shows that with one exception, changes in tone are lower after the adoption of state-funding labels.

Methods

Datasets

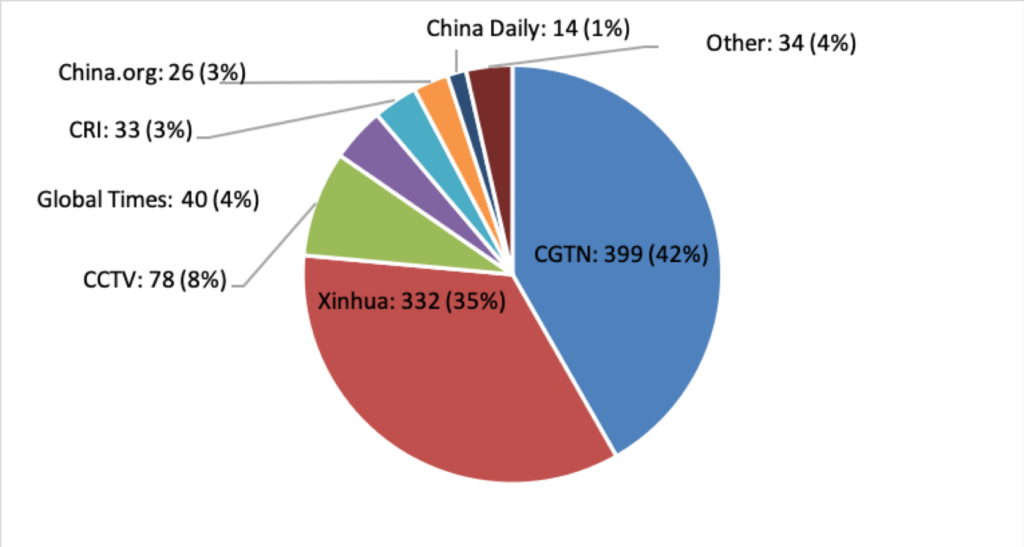

We use the Facebook Ads Library API to collect all advertisements posted by Chinese state media pages from 2018 to 2020 (Facebook, 2021). Most Chinese state media pages are already labeled by Facebook (Facebook, 2020), but some affiliated pages are not labeled, which we include in our dataset. There are 956 ads posted by 33 pages, many representing localized versions of other pages. A handful of major pages post the majority of advertisements, as shown in Figure 8.

For each advertisement, we determine the number of impressions in each country on each day the advertisement was shown. We also manually identify, for each advertisement, whether near-identical content, such as news articles, YouTube videos, or tweets, appears on other Chinese state media platforms. More details are available in Appendix A.

We are interested in assessing changes in news coverage about China. Therefore, we collect the average tone of articles published about China in each country on each day from 2018 to 2020, using the GDELT API (GDELT Project, 2017). GDELT labels the tone of each article using the valence (positive or negative) of words used in the article (Leetaru & Schrodt, 2013; Shook et al., 2012), a technique that achieves near-human accuracy (Hu & Liu, 2004; Kundi et al., 2014) across many different lexicons (Khoo & Johnkhan, 2017) and languages (Ihnaini & Mahmuddin, 2018; Pamungkas & Putri, 2016). The GDELT tool has been used in contexts similar to ours (Custer et al., 2019; Muller et al., 2021; Stern et al., 2020; Vargo et al., 2017). More details, including validation of this data, are available in Appendix B.

We also identified a set of topics mentioned heavily in the content of the Facebook advertisements. For each topic, we collected the number of articles containing a set of topic-related keywords published in each country on each day from 2018 to 2020. The keywords were used to narrow the set to coverage favorable towards China. Similar techniques have previously been used to quantify media “slant” (Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2010) and agenda-setting effects (Vargo et al., 2017). Table 1 shows the search terms used to find articles on each topic. Validations of these keywords as well as our tone measure are available in Appendix B.

| Topic area | Topic keywords |

| COVID-19 | (covid, coronavirus, OR “covid-19”) AND (recovery, recovered, treatment, treated, cured, OR discharged) |

| China’s poverty alleviation | poverty AND victory |

| Belt and Road Initiative | (“Belt and road” OR “one belt one road”) AND (connectivity, interconnected, cooperation, benefits, development, achievements, OR peace) |

| Huawei 5G | Huawei AND (trust OR safe) |

| Xinjiang internment camps | Xinjiang AND (terrorism, terrorist, OR terror) |

| Hong Kong protests | “Hong Kong” AND (riot OR rioter) |

Analysis

Chinese state media’s Facebook advertising increased sharply in many countries at the start of 2020. To evaluate the effect of a steep change in impressions, we use the PanelMatch framework (Imai, et al., 2018). This is a difference-in-differences estimator in which each treated observation is compared to a matched set of untreated observations in the same time period, offering an intuitive estimate of counterfactual outcomes.

To transform the impressions variable into a discrete treatment status, we used “low” and “high” thresholds set at 10 and 90% (commonly used in the study of signals [Levine, 1996]) of the maximum daily number of impressions, excluding outliers in the top decile. If a country’s number of impressions increased from below the “low” threshold to above the “high” threshold within a ten-day period, the country was considered treated on the day that the number of impressions exceeded the “high” threshold. The pre-treatment outcome was measured at the start of the ten-day period. Only countries with impressions below the “low” threshold for the full ten-day period could serve as untreated “control” observations.

We used a lag of ten days based on findings that the persuasive effects of political advertising decay rapidly, within several days (Gerber et al., 2011; Hill et al., 2013). The day treatment status changes was also included. We used a lead of seven days based on findings that news agendas, once set, tend to persist for seven days (Owen, 2019). We reported the average treatment effect among the treated with 95% Bayesian confidence intervals (Oliphant, 2006).

Matching between treated and untreated observations used five covariates: year-level arm sales from China (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2021), day-level diplomatic activity with China (ChinaPower, 2020), month-level foreign direct investment from China (American Enterprise Institute, 2020), month-level trade with China1Data for June 2018, October 2018, January 2020, and February 2020 are missing from this data source. (General Administration of Customs China, 2021; World Bank, 2021), and the day-level intensity score of bilateral events (Boschee et al., 2018), which has been used in similar contexts (Tellez & Roberts, 2019; Senekal & Kotzé, 2019). We used Mahalanobis distance matching with up to five matched units. There were 1,321 instances of countries switching from untreated to treated. More details are available in Appendix C.

Labels

We identified several Chinese state media pages not listed as state-controlled media in the Facebook Ads Library (see Appendix A). Because these pages were missing state-funding labels, we used them as a control group in a secondary difference-in-differences estimator. The outcome variable was the treatment effect of exposure to impressions on tone, the result from the previous experiment. The outcome was considered separately for the set of advertisements with labels after June 4, 2020, and those with no labels at any time. We took the mean outcomes for each group before and after June 4 and reported the standard difference-in-differences estimate of the effect of the state-funding policy change.

Limitations

Our study suffers from two central limitations. First, we suggest possible means by which intermedia agenda-setting may occur, but do not identify which, if any, accounts for our findings. This limits our ability to link Facebook advertisements directly to changes in media coverage. Additional research using data from Chinese state media website traffic and other social media platforms can disambiguate between the influence of Facebook advertisements and activity on other platforms, and can clarify the pathway by which Facebook advertisements may influence the media.

Second, our investigation of Facebook’s state-funding labels is highly limited. The post-label period in our data spans only June 4, 2020 to December 31, 2020, and there were few unlabeled advertisements in the control group. Moreover, because there was a single, platform-wide policy change, we were limited to a single treated and untreated unit, which leaves open the possibility of confounding.

Topics

- Asia

- / Propaganda

- / Social Media

Bibliography

American Enterprise Institute. (2020). China global investment tracker. https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/

Bjola, C. (2017, February 23). Propaganda in the digital age. Global Affairs, 3(3), 189–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2017.1427694

Boschee, E., Lautenschlager, J., O‘Brien, S., Shellman, S., Starz, J., & Ward, M. (2021, June 14). ICEWS weekly event data [Data set]. Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QI2T9A

Brady, A.-M. (2015, October). Authoritarianism goes global (II): China’s foreign propaganda machine. Journal of Democracy, 26(4), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0056

Carrer, G. (2020, August 4). Beijing speaking: How the Italian public broadcasting TV fell in love with China. Formiche. https://formiche.net/2020/04/beijing-speaking-how-italian-public-broadcasting-tv-fell-in-love-with-china/

Carter, E. B., & Carter, B. L. (2021, February 24). Questioning more: RT, outward-facing propaganda, and the post-west world order. Security Studies, 30(1), 49–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2021.1885730

Cheng, Z., Golan, G., & Kiousis, S. (2015, July 17). The second-level agenda-building function of the Xinhua News Agency. Journalism Practice, 10(6), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1063079

Chia, J. (2020, January 31). Thai media is outsourcing much of its coronavirus coverage to Beijing and that’s just the start. Thai Enquirer. https://www.thaienquirer.com/7301/thai-media-is-outsourcing-much-of-its-coronavirus-coverage-to-beijing-and-thats-just-the-start/

ChinaPower. (2020). Chinese high-level diplomatic activity, 2014-2020. https://chinapower.csis.org/data/chinese-high-level-diplomatic-activity-2014-2020/

Committee to Protect Journalists. (2020, August 12). Tech platforms struggle to label state-controlled media. https://cpj.org/2020/08/tech-platforms-struggle-to-label-state-controlled-media/

Cook, S. (2013, October 22). The long shadow of Chinese censorship: How the Communist Party’s media restrictions affect news outlets around the world. Center for International Media Assistance. https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CIMA-China_Sarah%20Cook.pdf

Cook, S. (2020). Beijing’s global megaphone: The expansion of Chinese Communist Party media influence since 2017. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/beijings-global-megaphone

Cook, S. (2021, February). China’s global media footprint: Democratic responses to expanding authoritarian influence. National Endowment for Democracy. https://www.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Chinas-Global-Media-Footprint-Democratic-Responses-to-Expanding-Authoritarian-Influence-Cook-Feb-2021.pdf

Custer, S., Prakash, M., Solis, J. A., Knight, R., & Lin, J. J. (2019, December 9). Influencing the narrative: How the Chinese government mobilizes students and media to burnish its image. AidData. https://www.aiddata.org/publications/influencing-the-narrative

Dearing, J., & Rogers, E. (1996). 6: Agenda-setting. In S. Chaffee (Ed.), Communication concepts (p. 33). Sage.

DiResta, R., Miller, C., Molter, V., Pomfret, J., & Tiffert, G. (2020). Telling China’s story: The Chinese Communist Party’s campaign to shape global narratives. Hoover Institution. https://cyber.fsi.stanford.edu/publication/telling-chinas-story

Facebook. (2021). Ad library. www.facebook.com/ads/library

Feezell, J. T. (2017, December 26). Agenda setting through social media: The importance of incidental news exposure and social filtering in the digital era. Political Research Quarterly, 71(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917744895

Ferrucci, P. (2018, March 26). Networked: Social media’s impact on news production in digital newsrooms. Newspaper Research Journal, 39(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532918761069

Fu, X. (2013). Inter-media agenda setting and social media: Understanding the interplay among Chinese social media, Chinese state-owned media and US news organizations on reporting the two sessions. (Master’s thesis, University of Florida). University of Florida Digital Collections. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UFE0046400/00001

GDELT Project. (2017, June 20). GDELT DOC 2.0 API debuts! https://blog.gdeltproject.org/gdelt-doc-2-0-api-debuts/

GDELT Project. (2018, May 14). Mapping the media: A geographic lookup of GDELT’s sources. https://blog.gdeltproject.org/mapping-the-media-a-geographic-lookup-of-gdelts-sources/

General Administration of Customs China. (2021). Preliminary release. http://english.customs.gov.cn/Statistics/Statistics?ColumnId=1

Gentzkow, M., & Shapiro, J. M. (2010, February 8). What drives media slant? Evidence from U.S. daily newspapers. Econometrica, 78(1), 35–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.3982/ECTA7195

Gerber, A. S., Gimpel, J. G., Green, D. P., & Shaw, D. R. (2011, February). How large and long-lasting are the persuasive effects of televised campaign ads? Results from a randomized field experiment. The American Political Science Review, 105(1), 135–150. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41480831

Gleicher, N. (2020, June 4). Labeling state-controlled media on Facebook. https://about.fb.com/news/2020/06/labeling-state-controlled-media/

Golan, G. (2007, February 17). Inter-media agenda setting and global news coverage: Assessing the influence of the New York Times on three network television evening news programs. Journalism Studies, 7(2), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700500533643

Gooch, E., Eckstrand, E., Mayers, C., & Ruiz, S. (2020, March 2). Using global media big data to understand China’s soft power efforts. RealClear Defense. https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2020/03/02/using_global_media_big_data_to_understand_chinas_soft_power_efforts_115083.html

Hill, S. J., Lo, J., Vavreck, L., & Zaller, J. (2013, October 18). How quickly we forget: The duration of persuasion effects from mass communication. Political Communication, 30(4), 521–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2013.828143

Hu, M., & Liu, B. (2004, August 22). Mining and summarizing customer reviews. Proceedings of the 10th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ‘04), Seattle, WA, United States, 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1145/1014052.1014073

Huang, Z. A., & Wang, R. (2020, February 7). ‘Panda engagement’ in China’s digitial public diplomacy. Asian Journal of Communication, 30(2), 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2020.1725075

Ihnaini, B., & Mahmuddin, M. (2018). Lexicon-based sentiment analysis of Arabic tweets: A survey. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 13(17), 7313–7322. http://dx.doi.org/10.36478/jeasci.2018.7313.7322

Imai, K., Kim, I. S., & Wang, E. (2018). Matching methods for causal inference with time-series cross-sectional data [Working paper]. https://imai.fas.harvard.edu/research/files/tscs.pdf

Insikt Group. (2020). Chinese state media seeks to influence international perceptions of COVID-19 pandemic. Recorded Future. https://www.recordedfuture.com/covid-19-chinese-media-influence

Jacob, J. (2020, July 14). ‘To tell China’s story well’: China’s international messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Report, 56(3), 374–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009445520930395

Jia, R., & Li, W. (2020, March). Public diplomacy networks: China’s public diplomacy communication practices in Twitter during two sessions. Public Relations, 46(1), 101818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.101818

Khoo, C. S., & Johnkhan, S.B. (2017, April 19). Lexicon-based sentiment analysis: Comparative evaluation of six sentiment lexicons. Journal of Information Science, 44(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0165551517703514

King, G., & Zeng, L. (2017, January 4). The dangers of extreme counterfactuals. Political Analysis, 14, 131–159. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpj004

Kundi, F. M., Khan, A., Ahmad, S., & Asghar, M. Z. (2014). Lexicon-based sentiment analysis in the social web. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 4(6), 238–248. http://www.textroad.com/pdf/JBASR/J.%20Basic.%20Appl.%20Sci.%20Res.,%204(6)238-248,%202014.pdf

Kurlantzick, J. (2020, January 8). Thailand’s press warms to Chinese state media. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/thailands-press-warms-chinese-state-media

Lee, A. M., Lewis, S. C., & Powers, M. (2012, November 20). Audience clicks and news placement: A study of time-lagged influence in online journalism. Communication Research, 41(4), 505–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212467031

Leetaru, K., & Schrodt, P. A. (2013. March 29). Global data on events, location and tone, 1979-2012 [presentation]. International Studies Association Annual Convention, San Francisco, CA, USA. International Studies Association. http://data.gdeltproject.org/documentation/ISA.2013.GDELT.pdf

Levine, W. (1996). The control handbook. CRC Press.

Lim, J. (2006, June 1). A cross-lagged analysis of agenda-setting among online news media. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(2), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900608300205

Lim, L., & Bergin, J. (2020). The China story: Reshaping the world’s media. International Federation of Journalists. https://www.ifj.org/fileadmin/user_upload/IFJ_ChinaReport_2020.pdf

Lunt, M. (2014, January 15). Selecting an appropriate caliper can be essential for achieving good balance with propensity score matching. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt212

Mantesso, S., & Zhou, C. (2019, February 7). China’s multi-billion dollar media campaign ‘a major threat for democracies’ around the world. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-02-08/chinas-foreign-media-push-a-major-threat-to-democracies/10733068

Mathes, R., & Pfetsch, B. (1991, March 1). The role of the alternative press in the agenda-building process: Spill-over effects and media opinion leadership. European Journal of Communication, 6(1), 33–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323191006001003

Molter, V., & DiResta, R. (2020, June 8). Pandemics & propaganda: How Chinese state media creates and propagates CCP coronavirus narratives. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-025

Moy, P., Tewksbury, D., & Rinke, E. M. (2016). Agenda-setting, priming, and framing. In K. B. Jensen, R. T. Craig, J. Pooley, & E. Rothenbuhler (Eds.), International encyclopedia of communication theory and philosophy. John Wiley & Sons.

Muller, S., Brazys, S., & Dukalskis, A. (2021, June 8). Discourse wars and ‘mask diplomacy’: China’s global image management in times of crisis. AidData. https://www.aiddata.org/publications/discourse-wars-and-mask-diplomacy-chinas-global-image-management-in-times-of-crisis

Musil, S. (2020, November 16). Facebook labels are reportedly ineffective at confining Trump’s false election claims. CNET. https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/facebook-labels-reportedly-ineffective-at-confining-trumps-false-election-claims/

Nassetta, J., & Gross, K. (2020, October 30). State media warning labels can counteract the effects of foreign misinformation. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(7). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-45

Nott, L. (2020, June 25). Political advertising on social media platforms. Human Rights Magazine, 45(3). https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/voting-in-2020/political-advertising-on-social-media-platforms/

Oliphant, T. E. (2006, December 5). A Bayesian perspective on estimating mean, variance, and standard-deviation from data. BYU Faculty Publications, 278. http://hdl.lib.byu.edu/1877/438

Owen, L. H. (2019, January 25). A typical big news story in 2018 lasted about 7 days (until we moved on to the next crisis). Nieman Lab. https://www.niemanlab.org/2019/01/a-typical-big-news-story-in-2018-lasted-about-7-days-until-we-moved-on-to-the-next-crisis/

Pamungkas, E. W., & Putri, D. G. P. (2016, August 1–3). An experimental study of lexicon-based sentiment analysis on Bahasa Indonesia. Proceedings of the 6th International Annual Engineering Seminar (InAES), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 28–31. https://doi.org/10.1109/INAES.2016.7821901

Protess, D., & McCombs, M. (1991). Agenda-setting: Readings on media, public opinion, and policymaking. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315538389

Purnell, N. (2021, April 2). Facebook staff fret over China’s ads portraying happy Muslims in Xinjiang. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-staff-fret-over-chinas-ads-portraying-happy-muslims-in-xinjiang-11617366096

Reuters Staff. (2020, May 4). Exclusive: Internal Chinese report warns Beijing faces Tiananmen-like global backlash over virus. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-china-sentiment-ex-idUSKBN22G19C

Schrodt, P. (2015, April 22–24). Event data in forecasting models: Where does it come from, what can it do? [Paper presentation]. Early Warning and Conflict, Oslo, Norway. https://parusanalytics.com/eventdata/presentations.dir/Schrodt.PRIO15.eventdata.slides.pdf

Senekal, B., & Kotzé, E. (2019, August 12). Open source intelligence (OSINT) for conflict monitoring in contemporary South Africa: Challenges and opportunities in a big data context. African Security Review, 28(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2019.1644357

Shook, E., Leetaru, K., Cao, G., Padmanabhan, A., & Wang, S. (2012, October 8–12). Happy or not: Generating topic-based emotional heatmaps for Culturomics using CyberGIS. Proceedings of the IEEE 8th International Conference on E-Science (e-Science). Chicago, IL, USA, 1–6. https://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/eScience.2012.6404440

Stern, S., Livan, G., & Smith, R. E. (2020, June 19). A network perspective on intermedia agenda-setting. Applied Network Science, 5(31). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41109-020-00272-4

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. (2021). SIPRI Arms Transfers Database. https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers

Stuart, E. (2010, February). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Stat Sci, 25(1), 1–21. https://www.doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313

Su, Y., & Lee, D. K. L. (2020, August 28). Delineating the transnational network agenda-setting model of mainstream newspaper and Twitter: A machine-learning approach. Journalism Studies, 21(15), 2113–2134. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1812421

Sweetser, K. D., Golan, G. J., & Wanta, W. (2008, April 23). Intermedia agenda-setting in television, advertising, and blogs during the 2004 election. Mass Communication and Society, 11(2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430701590267

Tellez, J., & Roberts, J. (2019, April 23). The rise of the Islamic State and changing patterns of cooperation in the Middle East. International Interactions, 45(3), 560–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2019.1604520

Twitter, Inc. (2019, August 19). Updating our advertising policies on state media. https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2019/advertising_policies_on_state_media

Valenzuela, S., Puente, S., & Flores, P. M. (2017, November 20). Comparing disaster news on Twitter and television: An intermedia agenda setting perspective. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 61(4), 615–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2017.1344673

Vandewalker, I. (2017, October 24). Oversight of federal political advertisement laws and regulations. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/oversight-federal-political-advertisement-laws-and-regulations

Vargo, C. J., & Guo, L. (2016, December 1). Networks, big data, and intermedia agenda setting: An analysis of traditional, partisan, and emerging online U.S. news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(4), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016679976

Vargo, C. J., Guo, L., & Amazeen, M. A. (2017, June 15). The agenda-setting power of fake news: A big data analysis of the online media landscape from 2014 to 2016. New Media & Society, 20(5), 2028–2049. http://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817712086

Vliegenthart, R., & Walgrave, S. (2008, December 1). The contingency of intermedia agenda setting: A longitudinal study in Belgium. Climactic Change, 85(4), 860–877. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900808500409

Weaver, D., McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. (2004). Agenda-setting research: Issues, attributes, and influences. In L. Kaid (Ed.), Handbook of political communication research (p. 269). Routledge.

World Bank. (2021). WITS Database. World Integrated Trade Solution. https://wits.worldbank.org

Xiao, E. (2021, March 30). China used Twitter, Facebook more than ever last year for Xinjiang propaganda. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-used-twitter-facebook-more-than-ever-last-year-for-xinjiang-propaganda-11617101007

Funding

No additional funding was provided.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

Institutional review was unnecessary because all data used in this project are publicly available.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KQ39K6

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to H.R. McMaster, Marc Grinberg, Erin Baggott Carter, Shelby Grossman, Milind Tambe, and Chelsea Burkey for guidance essential to the development of this research; and two anonymous reviewers, Renee DiResta, Fernando Cutz, Vanessa Molter, Hang Jiang, Sarah Cowan, Anshu Roy, and Jennifer Pan for their insightful comments.