Peer Reviewed

The relationship between conspiracy theory beliefs and political violence

Article Metrics

8

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Recent instances of political violence have prompted concerns over the relationship between conspiracy theory beliefs and violence. Here, we examine the relationships between beliefs in various conspiracy theories and three operationalizations of violence—support for political violence, self-reported engagement in political violence, and engagement in non-political conflict. While we did observe significant correlations between most conspiracy theory beliefs and (support for) violence, we also observed considerable variability in the correlations. We found that this variability is related to the popularity of the conspiracy theories. Specifically, conspiracy theory beliefs that are more “fringe,” held by smaller groups of homogenous people, are likely to be more strongly correlated with (support for) violence than beliefs in more popular theories. Our findings have implications for those seeking to curtail conspiracy theory-related violence.

Research Questions

- What is the relationship between political violence and conspiracy theory beliefs?

- Are beliefs in some conspiracy theories more likely to correlate with support for political violence or actual violent behavior than beliefs in other conspiracy theories?

- How has the correlation between support for political violence and generalized conspiracy thinking changed over the last decade?

Essay Summary

- The strength of the relationship between conspiracy theory beliefs and support for political violence varies across specific conspiracy theories, although the correlation is positive and statistically significant for 42 of 44 conspiracy theories examined. In other words, the stronger one’s beliefs in most conspiracy theories, the more likely they are to support political violence.

- The relationship between conspiracy theory beliefs and violence does not depend on the measure of violence, of which we employed three: 1) attitudinal support for political violence, 2) the self-reported commission of actual political violence, or 3) engagement in non-political violent interpersonal conflict.

- The strength of the connection between conspiracy theory beliefs and each measure of violence we employed tends to correspond to the popularity of the conspiracy theory, such that beliefs in less popular conspiracy theories are more strongly correlated with attitudinal and behavioral measures of violence. Across all conspiracy theory beliefs and measures of (support for) violence, the correlation between the popularity of a conspiracy theory and the connection between belief in that theory and violence is moderately strong at r(74) = -0.42 (p < .001).

- The correlation between attitudinal support for political violence and the general tendency to interpret events and circumstances as the product of conspiracies tripled in magnitude between 2012 and 2022.

- As human behavior—particularly behavior involving rare events, like political violence—is hard to predict, numerous questions remain about the causal connection between conspiracy theories and political violence. As such, researchers, journalists, and policymakers should carefully consider how, where, and when to intervene on conspiracy theory beliefs, perhaps focusing on those beliefs that exhibit the strongest connections to violence.

Implications

Recent events, like the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, have spurred a renewed scholarly interest in the causes of political violence (Armaly & Enders, 2022; Landry et al., 2024; Munis et al., 2023; Piazza, 2023; Zeitzoff, 2023). Notably, numerous studies have hypothesized a connection between support for, or the commission of, violence and beliefs in conspiracy theories (Baum et al., 2023; Bond & Neville-Shepard, 2023; Davis, 2024; Vanderwee & Droogan, 2023). For example, Jolley and Paterson (2020) showed that beliefs in conspiracy theories alleging that 5G cellular technology spread the COVID-19 virus are correlated with justifications for, and a general willingness to engage in, violence. Similarly, Armaly et al. (2022) found that support for the QAnon movement, a group based on conspiracy theories about the supposed “deep state” (Enders, Uscinski, Klofstad, & Stoller, 2022), is related to support for both political violence in the abstract and the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6.

While scholars are finding connections between conspiracy theory beliefs and violence, the ability to make generalizable claims about this relationship is hindered by the fact that most studies 1) consider only a small number of conspiracy theories and 2) employ limited measures of violence-related beliefs, intentions, and behaviors. As it stands, extant studies can only reveal that some forms of political violence, or support thereof, are related to some conspiracy theory beliefs. We attempt to advance our understanding of these relationships by considering the relationships between numerous forms of conspiracism and different measures of violence. Our goal is to understand whether there are generalizable conclusions that can be drawn about these relationships.

Employing 44 conspiracy theories that differ in their popularity, the topics they address, and other characteristics, as well as three different manifestations of violence (attitudinal support for political violence, the self-reported commission of political violence, and the self-reported commission of interpersonal conflict), we found that the strength of the relationship between conspiracy theory beliefs and (support for) violence varies depending on which conspiracy theory belief we examine, although most conspiracy theory beliefs are significantly, positively correlated. Additionally, the strength of these relationships is correlated with the conspiracy theories’ popularity such that, on average, popular conspiracy theories have weaker connections to our measures of violence. We also found that the relationship between violence and conspiracism can vary over time. Indeed, the correlation between attitudinal support for political violence and the general tendency toward conspiracy theorizing tripled in strength between 2012 and 2022. Finally, we did not find obvious differences across operationalizations of (political) violence: For the most part, conspiracy theory beliefs that were correlated with one operationalization of violence were similarly correlated with other operationalizations of violence. These findings have several implications for how government officials, scholars, journalists, and other practitioners address the pernicious effects of conspiracy theories.

What is the link between conspiracy theories and violence?

Conspiracy theories provide explanations of events and circumstances that point to the secret actions of powerful malevolent actors (Uscinski & Enders, 2023). Conspiracy theories are considered “theories” in the colloquial sense that their claims have yet to be deemed (likely to be) true by appropriate experts using data and methods that can be openly evaluated and challenged by others (Levy, 2007). While any given conspiracy theory could potentially be true (Dentith, 2022), many conspiracy theories are likely to be false (Harris, 2022). Given their dubious epistemic features, beliefs in conspiracy theories may create an alternative social reality for believers in which “non-normative behavior is a natural consequence” (Pummerer, 2022). For example, if someone believed that a shadowy group of powerful people was intent on causing them harm, they may be more likely to act against that group.

This leads to the first potential connection between beliefs in conspiracy theories and violence: People might want to “fight fire with fire” by using violence in order to thwart a perceived conspiracy or punish a perceived conspirator. There are numerous anecdotal accounts of conspiracy theory believers acting violently in hopes of foiling a supposed conspiracy (e.g., Obaidi et al., 2022). Examples include the individuals who believe in election fraud who stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021 (United States Attorney’s Office, 2024), the believers in a widespread child “grooming” scheme who committed various acts of violence against drag shows and the LGBTQ+ community (Padgett, 2023), and the believers in the “white replacement” conspiracy theory who have engaged in mass shootings of Jews, African-Americans, and other minority groups (Klofstad et al., 2024).

However, if conspiracy theories reliably caused believers to take violent actions, the vast majority of Americans would be perpetrating violence, given the sheer prevalence of conspiracy theory beliefs (Uscinski & Enders, 2023). Fortunately, conspiracy theory-induced violence is relatively rare, despite the popularity of many conspiracy theories (Enders & Uscinski, 2022). For example, while about a third of Americans believe that the 2020 election was rigged (Fortinsky, 2024), only a tiny fraction of those believers attended President Trump’s “stop the steal” rally on January 6, 2021, and only a fraction of those attendees engaged in violence at the Capitol (United States Attorney’s Office, 2024). It seems unlikely that conspiracy theory beliefs single-handedly cause believers to commit violence or, for that matter, actions of any kind. If conspiracy theory beliefs only rarely, on their own, motivate believers to engage in violent actions, then researchers should be cautious in ascribing violent intentions to believers.

A second potential connection linking beliefs in conspiracy theories and violence focuses on the believers and their preexisting attitudes, personality traits, and behavioral inclinations (Uscinski, Enders, Klofstad, & Stoler, 2022): People who harbor nonnormative personality traits and intentions may be the most likely to 1) engage in nonnormative behaviors and, concurrently, 2) adopt conspiracy theory beliefs(Enders, Uscinski, Klofstad, & Stoller, 2022). It may even be the case that individuals adopt conspiracy theories as rationalizations for actions they would have taken anyway (Williams, 2022), meaning that conspiracy theory beliefs may actually be the causal product of behavioral intentions in some cases (van Prooijen & Böhm, 2023). A significant body of research provides suggestive evidence for these alternative possibilities: Many of the longstanding antisocial attitudes and personality traits linked to violent behavior—e.g., dark tetrad traits like psychopathy (Pavlović & Franc, 2023; Yendell et al., 2022), Manichean worldviews (Rathje, 2022), and a willingness to engage in Machiavellian tactics and criminal behavior (Pavlović & Wertag, 2021)—also predict conspiracy theory beliefs (Douglas & Sutton, 2011; Enders et al., 2023; Jolley et al., 2019; Klofstad et al., 2024; Uscinski, Enders, Diekman, et al., 2022).

Importantly, the individuals who possess the types of antisocial traits that predict violent attitudes, intentions, and behaviors are more likely to adopt beliefs in conspiracy theories that are socially verboten. By this, we mean that the ideas are not just seen as epistemically suspect (Thalmann, 2019), but as especially taboo given what they claim and who they accuse. This may be because antisocial traits make individuals less likely to engage in prosocial behaviors, care about the welfare of others, and adhere to social norms, instead fostering a willingness to espouse ideas that others would not (Spain et al., 2014). For example, it is considered especially taboo in the West to espouse conspiracy theories holding that the Holocaust did not happen (Smallpage et al., 2022), that mass shootings are “false flag” events (Lantian et al., 2018), and that white people are victims of a replacement scheme (Wintemute et al., 2024). It is precisely beliefs such as these that are most strongly linked to antisocial personality traits and attitudes (Charny, 2017; Klofstad et al., 2024; Uscinski, Enders, Diekman, et al., 2022; Yelland & Stone, 1996). Moreover, individuals exhibiting antisocial traits may be more likely to not only adopt conspiracy theories that most other individuals would reject, but also believe more conspiracy theories in total (Enders, Klofstad, et al., 2023).

A third potential connection linking beliefs in conspiracy theories and violence focuses on the mental states and psychopathologies of the believers (Jolley & Paterson, 2020): People who adopt conspiracy theories may be willing to act on their conspiracy theory beliefs only after a shift in mental state (e.g., the onset of anger, anxiety, paranoia, or depression). For example, Baum et al. (2023) found that “among those who hold conspiracy beliefs and/or have participatory inclinations, depression is positively associated with support for election violence and the January 6 Capitol riots” (p. 575).

Finally, the prejudiced nature, salience, and sources of the conspiracy theories might also foster a link between violence and beliefs in conspiracy theories. More specifically, when a conspiracy theory scapegoats an outgroup (providing a target for violence), suggests that there is an imminent threat, or is endorsed by cues from trusted sources of information (Armaly et al., 2022; Klofstad et al., 2024; Ntontis et al., 2024; Riley, 2022), the connection between beliefs and violence may become stronger (Bracke & Aguilar, 2024; Jolley et al., 2022; Prooijen, 2020).

Having laid out some possibilities, we reiterate that the causes behind human behavior are difficult to determine (Bailey et al., 2024), especially with rare events like acts of political violence. By providing a broader window into the connection between violence and a wide range of conspiracy theory beliefs, we hope to provide some clues as to which beliefs might require more attention from practitioners seeking to quell the potential pernicious effects of conspiracy theories.

Conspiracy theories are not created equal

Conspiracy theories, while sharing certain elements and general narrative structure (Douglas & Sutton, 2023), should not be treated as if they are interchangeable. Different conspiracy theories attract different believers with different constellations of personality traits, political ideologies, worldviews, life experiences, and other characteristics (e.g., Enders et al., 2022), including past engagement in or support for violence (Hebel-Sela et al., 2022; Uscinski, Enders, Diekman, et al., 2022).

While most of the conspiracy theory beliefs we examine are significantly correlated with (support for) violence, some are not correlated, and others are weakly correlated. Whereas the connection between believing that 5G spreads COVID-19 and support for the destruction of 5G cellular towers during the pandemic may seem straightforward (Jolley & Paterson, 2020), perhaps it is equally straightforward to expect that a widely believed conspiracy theory about the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963 has, at best, a weak connection to violence. This is to say that, regardless of the causal process by which violence and conspiracy theory beliefs become linked, one should not assume that the patterns involving one conspiracy theory generalize to other conspiracy theories.

Popular conspiracy theories have weaker associations with violence

We found that the relationship between violence and conspiracy theory beliefs varies depending on the popularity of conspiracy theories. In particular, highly popular conspiracy theories tend to be more weakly associated with (support for) violence than less popular conspiracy theories. Across all conspiracy theory beliefs and measures of (support for) violence, the correlation between the popularity of a conspiracy theory and the connection between belief in that theory and violence is moderately strong at r(74) = -0.42 (p < .001).

This connection may have something to do with the fact that support for and engagement with political violence is rare: popular conspiracy theories, as a function of their popularity, attract a wider group of believers with more variability in their individual-level characteristics. As such, the correlation between (support for) violence and belief is relatively weaker. In some sense, this may merely amount to a “numbers game.” Consider, for example, that for more than 60 years, a majority of Americans have believed that JFK’s assassination was the work of a broad conspiracy that expanded well beyond Lee Harvey Oswald (Swift, 2013). However, far fewer than 50% of Americans have either engaged in politically violent behavior or are supportive of political violence (Jacob, 2024). Thus, it stands to reason that, even if a large proportion of individuals who are more psychologically and attitudinally disposed toward potentially engaging in violent acts are attracted to this conspiracy theory, the correlation between this belief and violence is still likely to be (relatively) weak. In practical terms, trying to identify the perpetrators of future violence from this belief would be, at best, inefficient and unreliable.

We found that conspiracy theory beliefs that are more “fringe”—held by smaller groups of presumably more homogenous people—have a better chance than more popular theories of being strongly correlated with (support for) violence. This is, again, partially a numbers game in that only a minority of individuals support or take part in political violence in the United States. This finding also suggests that individuals who attitudinally support political violence or possess psychological traits conducive to the commission of violence are more attracted to low-popularity, or fringe, conspiracy theories, thereby resulting in a stronger correlation between beliefs in low-popularity conspiracy theories and violence. Consider, for example, the conspiracy theory belief we find to be most strongly correlated with support for violence—that the number of Jews killed by the Nazis during World War II has been exaggerated on purpose. Given the well-known penchant for violent rhetoric and behaviors among Neo Nazis, white supremacists, and other antisemitic groups for which this belief is highly animating (Davis, 2024; Klofstad et al., 2024; Vanderwee & Droogan, 2023), it stands to reason that the connection between violence and belief is more intimate than it is for the JFK conspiracy theory. The two aforementioned possibilities—perhaps even a combination of the two—seem most likely to account for the correlation between violence and beliefs across the greatest number of theories: 1) individuals with nonnormative tendencies may espouse those beliefs due to their personalities which allow them to engage with stigmatized conspiracy theories that most people would reject, and 2) the stigmatized conspiracy theories themselves may be more likely to promote violent attitudes and violence to a greater degree than more popular theories (hence, why they are stigmatized in the first place). Importantly, we note that the popularity, social acceptability/stigmatization, and salience of conspiracy theories can vary across political contexts and over time.

The relationship between generalized conspiracy thinking and violence has strengthened

Conspiracy thinking is the predisposition to interpret events and circumstances as the product of conspiracies, regardless of subject matter. Rather than speaking to specific beliefs in specific conspiracy theories, it is a more generalized worldview (Enders et al., 2023) that is highly predictive of beliefs in specific conspiracy theories (Uscinski, Enders, Diekman, et al., 2022). Contrary to much popular speculation (Guilhot & Moyn, 2020; Stanton, 2020; Willingham, 2020), the average level of conspiracy thinking and general shape of its distribution is quite stable over time (Uscinski, Enders, Klofstad, et al., 2022). However, we found that the correlation between conspiracy thinking and support for political violence has tripled in magnitude between 2012 and 2022.

With the available data, which is unfortunately sparse prior to 2016, we can only speculate about the reasons for the increasing strength of this relationship, which does not appear to be the product of an increase in conspiracy-minded individuals. Instead, it could perhaps be due to a steady rise in polarization or a decline in institutional trust and support for democracy. It could also be due to Donald Trump’s conspiratorial and violent rhetoric, which may have tied conspiratorial worldviews with beliefs to thoughts of violence for some supporters or strengthened existing ties. It could also be the case that previously conspiracy-minded individuals have become more supportive of violence over time, or that people who are supportive of violence have become more conspiracy-minded over time. Given the lack of individual-level longitudinal/panel data, especially in the pre-Trump years, we are left to speculate about the process by which the strength of the relationship has increased. Nevertheless, the trend is troubling, and more data collection efforts are needed to better track this relationship into the future.

Journalists and policymakers should proceed with caution

Both our empirical findings and the questions they raise have implications for journalistic coverage of conspiracy theories and potential solutions to the societal problems oftentimes associated with conspiracy theories. First, journalists and policymakers must recognize that specific conspiracy theories are not interchangeable; rather, they are differentially correlated with a variety of political and psychological characteristics (Uscinski, Enders, Diekman, et al., 2022). Even though conspiracy theories about Taylor Swift and Kate Middleton generate consumer interest (e.g., Newitz, 2024), they might not be associated with violence or other troubling outcomes. We recommend focusing attention on the conspiracy theories that are more likely to be believed by individuals who are supportive of the use of political violence, who report actually engaging in violent behavior, or who exhibit other correlates of violence. To aid in this effort, researchers and governmental entities should more carefully track conspiracy theory-linked violence in hopes of 1) learning what conspiracy theories are most intertwined with violence at any given time and 2) developing models of how conspiracy theory beliefs cause or otherwise promote and relate to violence.

Second, it is critical that journalists, policymakers, and researchers alike understand that studies of conspiracy theory beliefs tell us about people, not ideas. Most individuals who believe in conspiracy theories will likely never act on them in a nonnormative way. If a conspiracy theory is linked to a behavior or attitude, it is potentially because individuals who believe in the conspiracy theory tend also to exhibit that behavior or attitude, not necessarily because exposure to a particular conspiracy theory caused a change in individuals. The people who believe in conspiracy theories are complicated—what they believe and how they act are the product of a complex interplay of pre-existing beliefs, worldviews, ideologies, identities, experiences, and contextual factors. The situational and environmental factors in which conspiracy theories are shared and acted upon deserve further investigation as well: It may very well be the case that media and political actors serve as critical triggers for believers to act out in violent ways (Nacos et al., 2020). Recent research shows that the perceived strength of prosocial norms is greater when norm-breaking is explicitly identified (Tirion et al., 2024). Perhaps, then, one of the most efficacious interventions policymakers, journalists, and pundits can engage in is calling out norm violations when they occur. For example, violent rhetoric by conspiratorial groups and leaders should be immediately treated as a norm violation and forcefully condemned.

Finally, coverage of conspiracy theories and their believers and interventions designed to address beliefs and believers should take seriously the fact that conspiracy theory believers are not only complicated in their own right but also that the conspiracy theories differ in who they attract. In short, we need more research on how conspiracy theories relate to troublesome social outcomes such as violence and other anti-democratic tendencies. We also urge greater nuance in the way conspiracy theories are discussed in news media and by societal leaders and encourage more research into the complicated causal interplay between conspiracy theory beliefs, behaviors, pre-existing dispositions, and environmental factors.

Findings

Finding 1: Support for political violence is differentially correlated with beliefs in specific conspiracy theories.

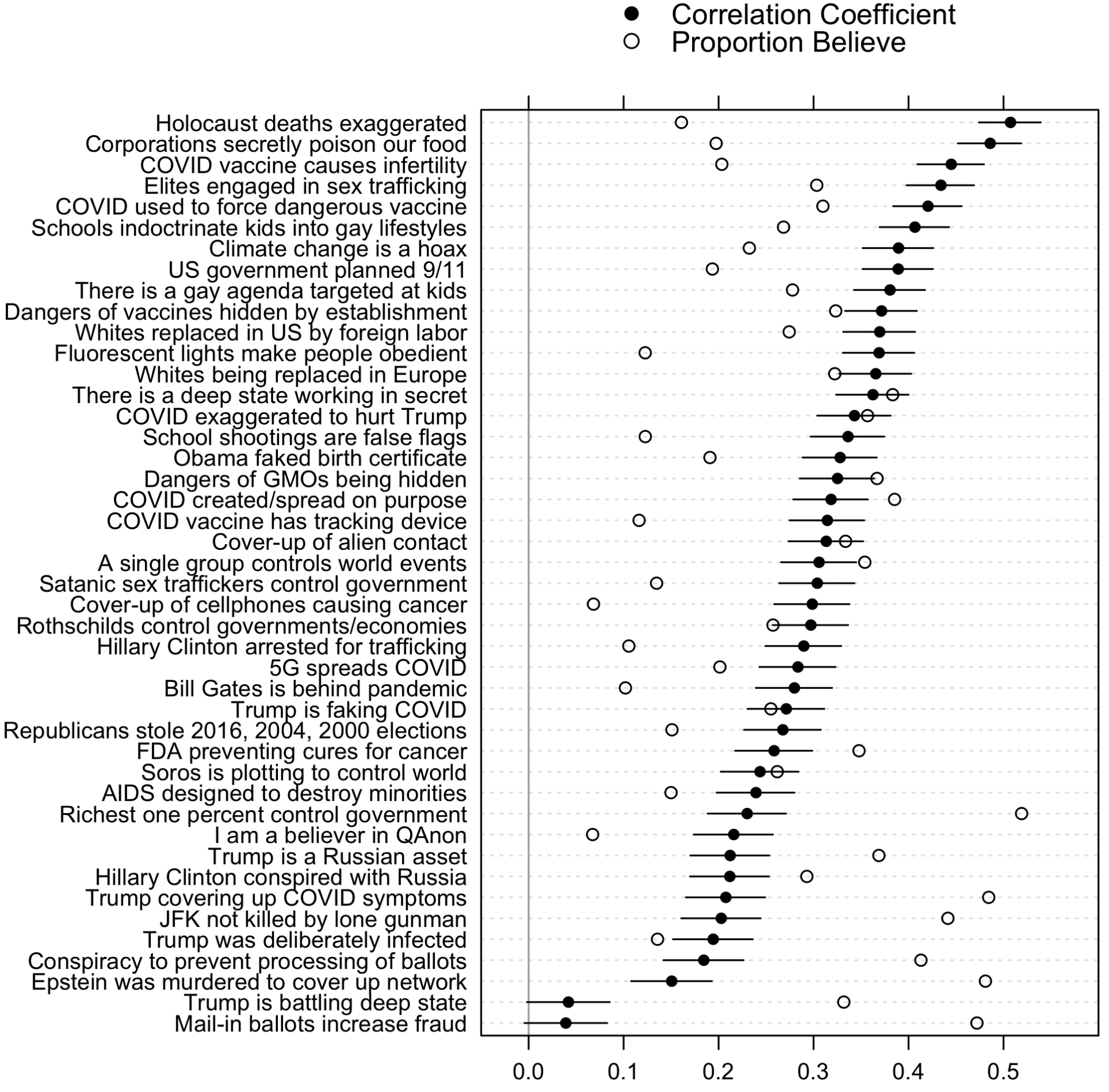

In Figure 1, we plot two quantities. The closed circles represent the correlation between belief in each conspiracy theory (summarized along the vertical axis) and support for political violence, which is measured vis-à-vis reactions to the statement, “violence is sometimes an acceptable way for Americans to express their disagreement with the government” using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree). We employed this general measure of support for political violence to broadly capture support for any form of political violence that believers in any conspiracy theory may want to commit. The open circles represent the proportion of respondents who chose either “agree” or “strongly agree” in reaction to each conspiracy theory (see the Appendix for full question wording for each conspiracy theory question).

First, we observed that most of the conspiracy theory beliefs we investigated (42 out of 44) are significantly and positively related to support for political violence (correlations range from r = .04 to r = .51). The average correlation between the 44 conspiracy theory beliefs depicted in Figure 1 and support for political violence is r = .30. We observed the strongest correlations with conspiracy theories alleging that Holocaust casualties have been exaggerated (r = .51) and that corporations are poisoning our food (r = .49).

Second, we observed a roughly X-shaped pattern between 1) the proportion of individuals expressing belief in each conspiracy theory and 2) the correlation between the percentage of our samples believing in that conspiracy theory and support for violence such that more popular conspiracy theories are less strongly correlated with support for political violence. Indeed, the correlation between the two quantities (i.e., those represented by the open and closed circles) is r(42) = -.34, p < .05. In other words, as the proportion of individuals believing a given conspiracy theory increases, the weaker the connection between belief in that theory and support for violence. Interestingly, QAnon, a conspiracy theory that often makes headlines due to the actions of some believers (e.g., Li, 2022), is not among the conspiracy theories most strongly positively correlated with support for violence, though some of the other conspiracy theories oftentimes associated with QAnon believers (e.g., those regarding the deep state or Satanic sex traffickers) are relatively strongly positively correlated.

Finding 2: Past violent and conflictual behavior is also differentially correlated with conspiracy theory beliefs.

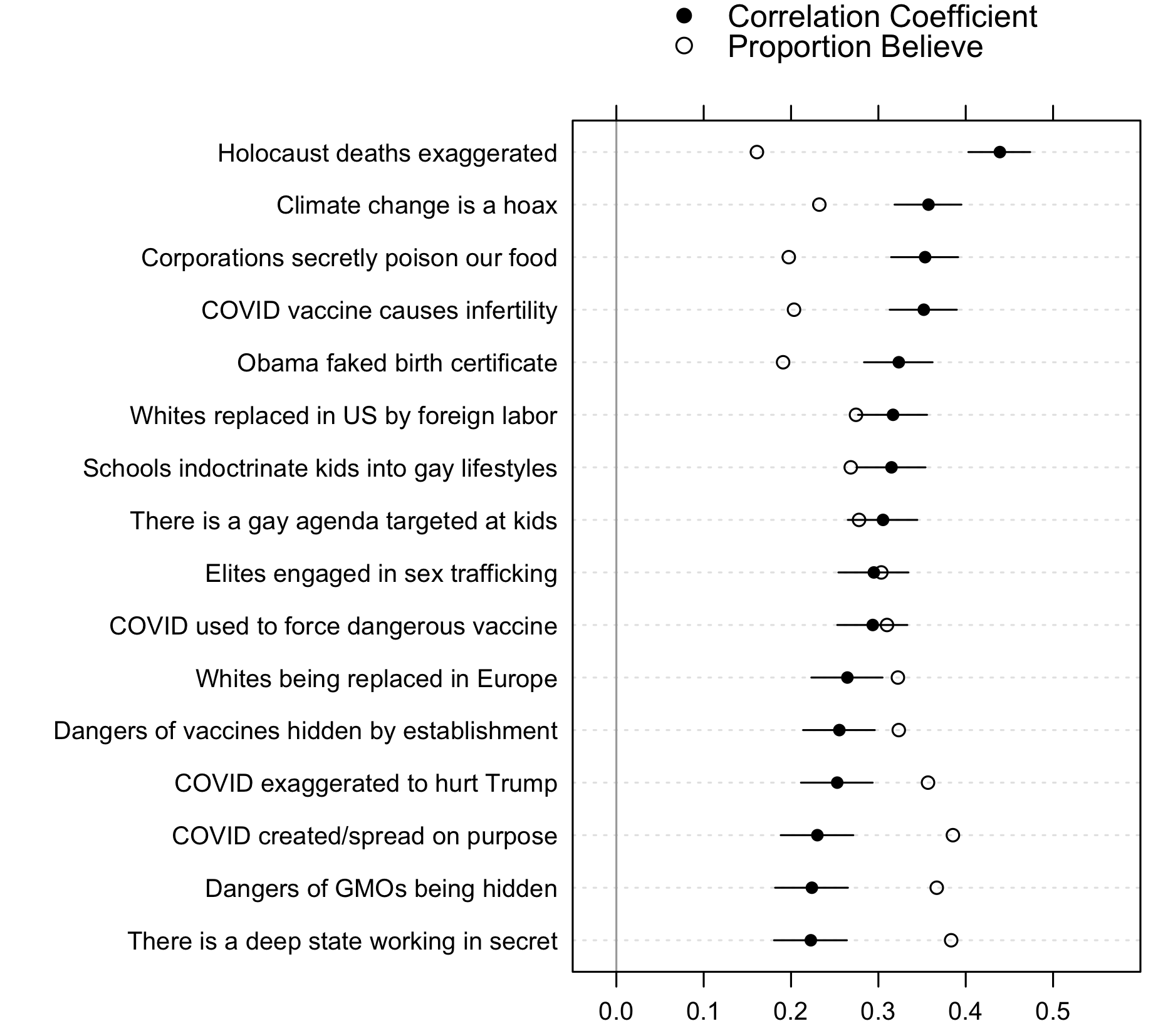

To both buttress the findings presented above and expand our analysis beyond attitudinal support for political violence, we asked respondents whether and how frequently they actually “committed violence for a political cause,” with the response options including 1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = 3-5 times, and 4 = more than 5 times. While we do not offer specific predictions about how patterns may differ from other measures of (support for) violence, we do believe it is important to provide a comprehensive approach to assessing the differential relationship between conspiracism and violence, especially in light of the fact that the literature remains divided on how to best capture (support for) violence (e.g., Westwood et al., 2022). Just as we employed many different conspiracy theory beliefs, we utilized different measures of (support for) violence. Figure 2 depicts the same quantities as Figure 1, substituting this behavioral measure of past engagement in political violence for the attitudinal measure of support for political violence.

As in Figure 1, we observed variability in the correlation between engaging in political violence and conspiracy theory beliefs, with correlation coefficients (all statistically significant at p < .05) ranging from r(1997)= .44 to r(1997) = .22. The average correlation is .30. We also observed an even clearer X-shaped pattern between the proportion of believers and the aforementioned correlation; indeed, these two quantities are strongly negatively correlated, r(14) = -.94 (p < .001).

To test the boundaries of the relationship between violence and conspiracy theory beliefs, we also utilized a battery of questions about non-political interpersonal conflict. We asked respondents, “During the past 12 months, have you done the following things when having a disagreement with another person?” Respondents were able to select “yes” or “no” to the following sub-questions:

- Insulted or swore at someone?

- Pushed, grabbed, or shoved someone?

- Threatened to hit another person?

- Hit, kicked, bit, or slapped someone?

- Beat someone up?

- Threatened to use, or actually used, a knife or gun on someone?

We simply counted the number of “yes” responses across questions to generate a measure of conflictual behavior and replicated previous analyses in structure. The results are presented in Figure 3.

Very similar to Figures 1 and 2, we observed variability in the correlation between conflictual behavior and conspiracy theory beliefs, ranging from r(1999) = .39 to r(1999) = .24 (all of which are statistically significant at p < .05) with an average correlation of .30. Again, we also observed a fairly clear, albeit less pronounced, X-shaped pattern between the proportion of believers and the correlation between conflictual behavior and belief; the negative correlation between the two quantities is still quite strong, r(14) = -.67, p < .01.

Finding 3: The correlation between support for political violence and the conspiracy thinking predisposition increased from 2012-2022.

Finally, we replicated the analyses above, substituting measures of beliefs in specific conspiracy theories with a measure of the general predisposition to interpret events and circumstances through a conspiratorial lens. The conspiracy thinking predisposition was measured using the American Conspiracy Thinking Scale (ACTS), which is an index of answers—using five-category “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” response options—to the following four statements:

- Much of our lives are being controlled by plots hatched in secret places.

- Even though we live in a democracy, a few people will always run things anyway.

- The people who really ‘run’ the country, are not known to the voters.

- Big events like wars, recessions, and the outcomes of elections are controlled by small groups of people who are working in secret against the rest of us.

As this measure, along with the attitudinal violence support question about whether “violence is sometimes an acceptable way for Americans to express their disagreement with the government,” was fielded on multiple surveys between 2012 and 2022, we can examine the correlation between the two over time in a way that we cannot with most specific conspiracy theory belief questions.

Figure 4 depicts the correlation for every year in which it is available (note that there are two surveys in 2020, in March and October). In every year, the correlation between the ACTS and support for political violence is statistically significant (p < .05). Rather than proving static, the positive correlation grew stronger, from r(1196)= .14 in 2012 to r(1996)= .43 in 2022. This tripling of magnitude over a decade underscores that not only is there variability in the way violence relates to different conspiracy theories, but there is also the potential that the relationship between violence varies for a given conspiracy theory over time, just as we observed in Figure 4 with a generalized worldview.

Methods

Figure 1 includes data from four surveys, each fielded by Qualtrics, in May 2022, May 2021, October 2020, and March 2020. Figures 2 and 3 depict data from May 2022 only. In each case, Qualtrics and partner organizations utilized a quota sampling methodology to create a sample that matched 2019 U.S. Census American Community Survey records on sex, age, race, education, and income. In line with best practices for self-administered online questionnaires, multiple attention check questions were included in each questionnaire. Participants who failed to correctly complete all attention checks were excluded from the dataset. Participants who completed the questionnaire in less than one-half the median time calculated from a soft launch of the surveys were also not included in the dataset. Qualtrics complies fully with European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR) standards for protecting research subjects’ privacy and information.

Figure 4 includes data from all the surveys detailed above, as well as a July 2019 survey we commissioned to be fielded by Qualtrics in the fashion described above, and surveys we commissioned in October 2018, 2016, and 2012 as part of the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES). Differences in which datasets were employed across analyses correspond to data availability. For example, the ACTS is available on many surveys dating back to 2012, though not all of those surveys include questions about belief in specific conspiracy theories or support for violence. Only the May 2022 survey included measures of behavioral violence and conflictual tendencies. Across the eight surveys utilized to produce Figure 4, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability estimate for the ACTS ranges from 0.76–0.87 across the various surveys/years.

The sociodemographic composition and size of each sample we employed can be found in Appendix A. Question wording for all the conspiracy theory questions utilized in producing Figure 1 can be found in Appendix B. Question wording for all the conspiracy theory questions utilized in producing Figures 2 and 3 appears in Appendix C.

Topics

Bibliography

Armaly, M. T., Buckley, D. T., & Enders, A. M. (2022). Christian nationalism and political violence: Victimhood, racial identity, conspiracy, and support for the capitol attacks. Political Behavior, 44(2), 937–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09758-y

Armaly, M. T., & Enders, A. M. (2022). Who supports political violence? Perspectives on Politics, 22(2), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722001086

Bailey, D. H., Jung, A. J., Beltz, A. M., Eronen, M. I., Gische, C., Hamaker, E. L., Kording, K. P., Lebel, C., Lindquist, M. A., Moeller, J., Razi, A., Rohrer, J. M., Zhang, B., & Murayama, K. (2024). Causal inference on human behaviour. Nature Human Behaviour, 8(8), 1448–1459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01939-z

Baum, M. A., Druckman, J. N., Simonson, M. D., Lin, J., & Perlis, R. H. (2023). The political consequences of depression: How conspiracy beliefs, participatory inclinations, and depression affect support for political violence. American Journal of Political Science, 68, 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12827

Bond, B. E., & Neville-Shepard, R. (2023). The rise of presidential eschatology: Conspiracy theories, religion, and the January 6th insurrection. American Behavioral Scientist, 67(5), 681–696. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642211046557

Bracke, S., & Hernandez Aguilar, L. M. (2024). The politics of replacement: From “race suicide” to the “great replacement.” In L. M. Hernandez Aguilar & S. Bracke (Eds.), The politics of replacement (pp. 1–19). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003305927

Charny, I. W. (2017). A classification of denials of the holocaust and other genocides. In M. Lattimer (Ed.), Genocide and human rights (pp. 517–540). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351157568

Davis, M. (2024). Violence as method: The “white replacement,” “white genocide,” and “Eurabia” conspiracy theories and the biopolitics of networked violence. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2024.2304640

Dentith, M. R. X. (2022). Suspicious conspiracy theories. Synthese, 200(3), 243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03602-4

Douglas, K. M., & Sutton, R. M. (2011). Does it take one to know one? Endorsement of conspiracy theories is influenced by personal willingness to conspire. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50(3), 544–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02018.x

Douglas, K. M., & Sutton, R. M. (2023). What are conspiracy theories? A definitional approach to their correlates, consequences, and communication. Annual Review of Psychology, 74(1), 271–298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031329

Enders, A. M., Diekman, A., Klofstad, C., Murthi, M., Verdear, D., Wuchty, S., & Uscinski, J. (2023). On modeling the correlates of conspiracy thinking. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 8325. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34391-6

Enders, A. M., Farhart, C., Miller, J., Uscinski, J., Saunders, K., & Drochon, H. (2022). Are Republicans and conservatives more likely to believe conspiracy theories? Political Behavior, 45, 2001–2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09812-3

Enders, A. M., Klofstad, C., Stoler, J., & Uscinski, J. E. (2023). How anti-social personality traits and anti-establishment views promote beliefs in election fraud, QAnon, and COVID-19 conspiracy theories and misinformation. American Politics Research, 51(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673×221139434

Enders, A. M., & Uscinski, J. (2022). What’s the harm? Journal of Free Speech Law, 4(2), 415–444. https://www.journaloffreespeechlaw.org/endersuscinski.pdf

Enders, A. M., Uscinski, J., Klofstad, C., & Stoler, J. (2022). On the relationship between conspiracy theory beliefs, misinformation, and vaccine hesitancy. PLOS ONE, 17(10), e0276082. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276082

Enders, A. M., Uscinski, J., Klofstad, C., Wuchty, S., Seelig, M., Funchion, J., Murthi, M., Premaratne, K., & Stoler, J. (2022). Who supports QAanon? A case study in political extremism. Journal of Politics, 84(3), 1844–1849. https://doi.org/10.1086/717850

Fortinsky, S. (2024, January 2). One-third of adults in new poll say Biden’s election was illegitimate. The Hill. https://thehill.com/homenews/campaign/4384619-one-third-of-americans-say-biden-election-illegitimate

Guilhot, N., & Moyn, S. (2020, February 13). The Trump era is a golden age of conspiracy theories—on the right and left. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/13/trump-era-conspiracy-theories-left-right

Harris, K. R. (2022). Some problems with particularism. Synthese, 200(6), 447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03948-9

Hebel-Sela, S., Hameiri, B., & Halperin, E. (2022). The vicious cycle of violent intergroup conflicts and conspiracy theories. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101422

Jacob, M. (2024). Cross-national support for political violence. Polarization Research Lab. https://prlpublic.s3.amazonaws.com/reports/political_violence_comparative_public.html

Jolley, D., Douglas, K. M., Leite, A. C., & Schrader, T. (2019). Belief in conspiracy theories and intentions to engage in everyday crime. British Journal of Social Psychology, 58(3), 534–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12311

Jolley, D., Marques, M. D., & Cookson, D. (2022). Shining a spotlight on the dangerous consequences of conspiracy theories. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101363

Jolley, D., & Paterson, J. L. (2020). Pylons ablaze: Examining the role of 5G COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(3), 628–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12394

Klofstad, C., Christley, O., Diekman, A., Kübler, S., Enders, A. M., Funchion, J., Littrell, S., Murthi, M., Premaratne, K., Seelig, M., Verdear, D., Wuchty, S., Drochon, H., & Uscinski, J. (2024). Belief in White Replacement. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2024.2342834

Landry, A. P., Druckman, J. N., & Willer, R. (2024). Need for chaos and dehumanization are robustly associated with support for partisan violence, while political measures are not. Political Behavior, 46, 2631–2655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09934-w

Lantian, A., Muller, D., Nurra, C., Klein, O., Berjot, S., & Pantazi, M. (2018). Stigmatized beliefs: Conspiracy theories, anticipated negative evaluation of the self, and fear of social exclusion. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(7), 939–954. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2498

Levy, N. (2007). Radically socialized knowledge and conspiracy theories. Episteme, 4(2), 181–192 https://doi.org/10.3366/epi.2007.4.2.181

Li, D. K. (2022, September 14). Michigan man who killed his wife went down a ‘rabbit hole’ of conspiracy theories after Trump’s 2020 loss, daughter says. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/michigan-man-killed-wife-went-rabbit-hole-conspiracy-theories-trumps-2-rcna47701

Munis, B. K., Memovic, A., & Christley, O. R. (2023). Of rural resentment and storming capitols: An investigation of the geographic contours of support for political violence in the United States. Political Behavior, 46, 1791–1812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09895-6

Nacos, B. L., Shapiro, R. Y., & Bloch-Elkon, Y. (2020). Donald Trump: Aggressive rhetoric and political violence. Perspectives on Terrorism, 14(5), 2–25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26940036

Newitz, A. (2024, February 21). The Taylor Swift ‘psy op’ conspiracy theory offers a troubling lesson. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg26134793-500-the-taylor-swift-psy-op-conspiracy-theory-offers-a-troubling-lesson/

Ntontis, E., Jurstakova, K., Neville, F., Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. (2024). A warrant for violence? An analysis of Donald Trump’s speech before the U.S. Capitol attack. British Journal of Social Psychology, 63(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12679

Obaidi, M., Kunst, J., Ozer, S., & Kimel, S. Y. (2022). The “Great Replacement” conspiracy: How the perceived ousting of Whites can evoke violent extremism and Islamophobia. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(7), 1675–1695. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211028293

Padgett, D. (2023, October 25). Ohio man pleads guilty to firebombing church over drag queen events. The Advocate. https://www.advocate.com/law/firebombing-drag-queen-church

Pavlović, T., & Franc, R. (2023). Antiheroes fueled by injustice: Dark personality traits and perceived group relative deprivation in the prediction of violent extremism. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 15(3), 277–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2021.1930100

Pavlović, T., & Wertag, A. (2021). Proviolence as a mediator in the relationship between the dark personality traits and support for extremism. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110374

Piazza, J. A. (2023). Political polarization and political violence. Security Studies, 32(3), 476–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2023.2225780

Prooijen, J.-W. v. (2020). An existential threat model of conspiracy theories. European Psychologist, 25(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000381

Pummerer, L. (2022). Belief in conspiracy theories and non-normative behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101394

Rathje, J. (2022). Driven by conspiracies: The justification of violence among “Reichsbürger” and other conspiracy-ideological sovereignists in contemporary Germany. Perspectives on Terrorism, 16(6), 49–61. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27185091

Riley, J. K. (2022). Angry enough to riot: An analysis of in-group membership, misinformation, and violent rhetoric on TheDonald.win between election day and inauguration. Social Media + Society, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221109189

Smallpage, S. M., Enders, A. M., Drochon, H., & Uscinski, J. E. (2022). The impact of social desirability bias on conspiracy belief measurement across cultures. Political Science Research and Methods, 11(3), 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.1

Spain, S. M., Harms, P., & LeBreton, J. M. (2014). The dark side of personality at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(S1), S41–S60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1894

Stanton, Z. (2020, June 17). You’re living in the golden age of conspiracy theories. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/06/17/conspiracy-theories-pandemic-trump-2020-election-coronavirus-326530

Swift, A. (2013, November 15). Decades later, most Americans doubt lone gunman killed JFK. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/514310/decades-later-americans-doubt-lone-gunman-killed-jfk.aspx

Thalmann, K. (2019). The stigmatization of conspiracy theory since the 1950s: “A plot to make us look foolish.” Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429020353

Tirion, A. S. C., Mulder, L. B., Kurz, T., Koudenburg, N., Prosser, A. M. B., Bain, P., & Bolderdijk, J. W. (2024). The sound of silence: The importance of bystander support for confronters in the prevention of norm erosion. British Journal of Social Psychology, 63(2), 909–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12709

United States Attorney’s Office, District of Columbia. (2024). Three years since the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. https://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/36-months-jan-6-attack-capitol-0

Uscinski, J., & Enders, A. (2023). Conspiracy theories: A primer (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Uscinski, J., Enders, A., Diekman, A., Funchion, J., Klofstad, C., Kuebler, S., Murthi, M., Premaratne, K., Seelig, M., Verdear, D., & Wuchty, S. (2022). The psychological and political correlates of conspiracy theory beliefs. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 21672. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25617-0

Uscinski, J., Enders, A., Klofstad, C., Seelig, M., Drochon, H., Premaratne, K., & Murthi, M. (2022). Have beliefs in conspiracy theories increased over time? PLOS ONE, 17(7), e0270429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270429

Uscinski, J., Enders, A. M., Klofstad, C., & Stoler, J. (2022). Cause and effect: On the antecedents and consequences of conspiracy theory beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101364

van Prooijen, J.-W., & Böhm, N. (2023). Do conspiracy theories shape or rationalize vaccination hesitancy over time? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 15(4), 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506231181659

Vanderwee, J., & Droogan, J. (2023). Testing the link between conspiracy theories and violent extremism: A linguistic coding approach to far-right shooter manifestos. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2023.2258952

Westwood, S. J., Grimmer, J., Tyler, M., & Nall, C. (2022). Current research overstates American support for political violence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(12), e2116870119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116870119

Williams, D. (2022). The marketplace of rationalizations. Economics and Philosophy, 39(1), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266267121000389

Willingham, A. (2020, October 3). How the pandemic and politics gave us a golden age of conspiracy theories. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/03/us/conspiracy-theories-why-origins-pandemic-politics-trnd/index.html

Wintemute, G. J., Robinson, S. L., Tomsich, E. A., & Tancredi, D. J. (2024). Maga Republicans’ views of American democracy and society and support for political violence in the United States: Findings from a nationwide population-representative survey. PLOS ONE, 19(1), e0295747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295747

Yelland, L. M., & Stone, W. F. (1996). Belief in the Holocaust: Effects of personality and propaganda. Political Psychology, 17(3), 551–562. https://doi.org/10.2307/3791968

Yendell, A., Clemens, V., Schuler, J., & Decker, O. (2022). What makes a violent mind? The interplay of parental rearing, dark triad personality traits and propensity for violence in a sample of German adolescents. PLOS ONE, 17(6), e0268992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268992

Zeitzoff, T. (2023). Nasty politics: The logic of insults, threats, and incitement. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197679487.001.0001

Funding

The efforts of Uscinski and Klofstad are funded by NSF grant #2123635.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The survey protocols employed were approved by the University of Miami institutional review board. Human subjects provided informed consent.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VMEVYC