Peer Reviewed

The presumed influence of election misinformation on others reduces our own satisfaction with democracy

Article Metrics

12

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Pervasive political misinformation threatens the integrity of American electoral democracy but not in the manner most commonly examined. We argue the presumed influence of misinformation (PIM) may be just as pernicious, and widespread, as any direct influence that political misinformation may have on voters. Our online survey of 2,474 respondents in the United States shows that greater attention to political news heightens PIM on others as opposed to oneself, especially among Democrats and Independents. In turn, PIM on others reduces satisfaction with American electoral democracy, eroding the “virtuous circle” between news and democracy, and possibly commitment to democracy in the long-term.

Research Questions

- How is attention to political news and information associated with the presumed influence of misinformation on other voters?

- How is the presumed influence of misinformation on others, relative to oneself, associated with satisfaction with American electoral democracy?

- Do these relationships vary by partisan identification?

Essay Summary

- We conducted an online survey in March 2020 during the Democratic primaries with 2,474 respondents recruited to match the American population based on age, gender, race, and education.

- Respondents reported how much attention they paid to the 2020 election and politics in general, their political self-identification, presumed influence of misinformation (PIM) on themselves and others, and their satisfaction with American electoral democracy. Respondents, regardless of political identification, were significantly less satisfied with American democracy the more they believed misinformation influenced others relative to themselves. Moreover, PIM on others increased significantly among Democrats and Independents, though not Republicans, the more they paid attention to electoral and political news.

- Our findings highlight how the indirect effect of political misinformation through PIM on others goes beyond direct impacts of misinformation on attitudes and behaviors. Additionally, the increased amount of interest garnered by misinformation in political and media discourse may indirectly erode satisfaction in democracy among Democrats and Independents who pay a great deal of attention to political news by increasing their PIM on others.

- As democratic satisfaction is key to sustaining citizen participation, perceived legitimacy of electoral outcomes, and democratic commitment, high levels of PIM on others threaten the fundamentals of American democratic governance.

Implications

The news media have long been recognized as playing essential roles in reinforcing citizens’ participation and satisfaction with processes of participatory democracy within the context of a “virtuous circle” (Norris, 2000). Unfortunately, this virtuous circle has been polluted by an increase in false or misleading information in media and political discourse (i.e., misinformation) (Kelly et al., 2017). Contrary to the popular consensus that misinformation has major impacts on political attitudes and behavior, the scholarship on its direct effects has been mixed. Some studies show limited or no direct impact from misinformation, whilst others indicate significant impacts on political behavior (e.g., Bail et al., 2020; Gunther et al., 2019; Zimmerman & Kohring, 2020).

We propose to close this gap between public concern about misinformation and the evidence for its direct effects by asserting that the proliferation of misinformation in American discourse may have a subtle, pernicious, indirect effect through the concept of influence of presumed influence (IPI) (Gunther & Storey, 2003; Tal-Or et al., 2020). IPI refers to how much people perceive media as influencing others’ attitudes or actions, and how their reaction to this perceived influence affects their own attitudes or behaviors. A related concept is the “third-person effect” that refers to the tendency of individuals to overestimate the presumed influence of harmful media on others as compared with themselves (McLeod et al., 2001).

The concepts of presumed influence, and possible third-person effects of misinformation, are highly relevant to misinformation research, because they explain why the threat of misinformation is so salient for Americans. A 2019 Pew Research survey, for instance, found that half of Americans believe misinformation is a “very big problem” (Mitchell et al., 2019, p. 3). On the same survey, more than two-thirds of respondents (67%) reported that misinformation “creates a great deal of confusion” about the basic facts of current issues and events.

This concern about the presumed influence of misinformation (PIM) on others is driven by the ballooning salience of misinformation in everyday political discourse and news since the 2016 election. For example, between 2015 and 2019, the number of American TV news stories mentioning “misinformation” increased 323%, from 1,875 in 2015 to 6,071 in 2019, based on search results from the Internet TV news archive (www.archive.org). As a consequence, our study shows that greater attention to political news and information increases PIM on others, primarily among Democrats and Independents, most likely as it increases exposure to news and information about misinformation’s spread and potential impacts.

The PIM on others has been shown to increase public support for its censorship and regulation, consistent with previous research on the presumed influence of misinformation (e.g., Baek et al., 2019; Cheng & Chen, 2020; Ho et al., 2020). However, we posit that the human tendency to overestimate PIM on others has consequences that go beyond influencing attitudes about its regulation or censorship. We assert that regardless of whether or not people believe political misinformation they actually encounter or hear about, PIM on other voters erodes satisfaction with electoral democracy generally.

The reason why PIM on others erodes satisfaction with electoral democracy is based on the concept of procedural justice (Lind & Tyler, 1988). People are more satisfied with, and committed to, the “rules of the game” and decision outcomes, even when they are counter to their interests or desires, when they perceive that these decision processes are free, fair, just, and in which they feel they have a voice (Lind & Tyler, 1988; Lind et al., 1990). In turn, when people feel that the procedures used to make decisions are not fair or just and/or they do not have a sufficient voice in the outcome, then they are dissatisfied and lose commitment to the rules as a whole.

Electoral democracy is fundamentally a set of rules and procedures by which political leaders are selected and political decisions are made. When people’s preferred candidate or party may lose an election, they accept the loss and remain satisfied and committed to electoral democracy as long as they view that the procedures that determined the outcome were free and fair. On the other hand, when citizens feel that democracy’s procedures have been manipulated or tainted in some way, for example, due to the influence of misinformation, they are in turn less satisfied with it (Erlingsson et al., 2014; Magalhães, 2016; Norris, 2019; Tyler et al., 1985).

In this sense, PIM reduces satisfaction with electoral democracy when people believe that others have been unduly influenced or manipulated by misinformation, and thus they are less likely to view electoral processes and outcomes as fair and just (Cho & Kim, 2016). Our findings support this hypothesis, as PIM on others, controlling for PIM on self and other factors, significantly decreased satisfaction with electoral democracy in our analysis.

Returning to the “virtuous circle” between media and electoral democracy, we argue that this increased salience of misinformation and its presumed influence on others in everyday political discourse creates an indirect pathway, harming the virtuous circle. Though our findings show that attention to political news and information increases satisfaction with electoral democracy, consistent with the virtuous circle, at the same time attention to political news indirectly reduces satisfaction with electoral democracy by heightening the presumed influence of misinformation on others among Democrats and Independents.

This erosion of satisfaction with democratic processes due to PIM may have long-term effects on people’s commitment to those processes and to democratic politics as a whole (Erlingsson et al., 2014; Magalhães, 2016; Norris, 2019). Erosion of democratic satisfaction and commitment may lead to (1) decreased voter engagement, (2) placing greater impact on electoral outcomes rather than democratic processes, (3) winning candidates enjoying less legitimacy, and (4) increased political polarization. In these ways, we assert that misinformation substantially harms democracy regardless of how many people actually believe or endorse it.

Addressing the problem of PIM eroding satisfaction with electoral democracy is challenging. Similar to foreign terrorism (Mueller, 2006), its prevalence is not only a problem, but it is also an issue that creates an exaggerated fear amongst the public, sometimes driven by sensationalist reporting without sufficient context. Media organizations and reporters need to take the lead in reporting on, and fact-checking, misinformation in more nuanced and measured ways that do not overly exaggerate its impact on others. Journalism education could also contribute by providing journalists a deeper scientific understanding of the nature and extent of its influence on people. Media literacy campaigns and education, one of the most commonly cited solutions for decreasing vulnerability to misinformation (e.g., Guess et al., 2020; Vraga & Tully, 2019), could also help address this problem by including in their curriculum information that allows people to better assess the magnitude of threat from misinformation and to manage fears.

Findings

Our findings detail the mechanism, and the indirect effect, by which misinformation negatively impacts satisfaction with electoral democracy through its presumed influence on other voters, especially among Democrats and Independents.

Finding 1: For Democrats and Independents, the more attention they pay to news and information about the 2020 election and politics, the higher they rate the influence of misinformation on other voters. The pattern is unobservable for Republicans.

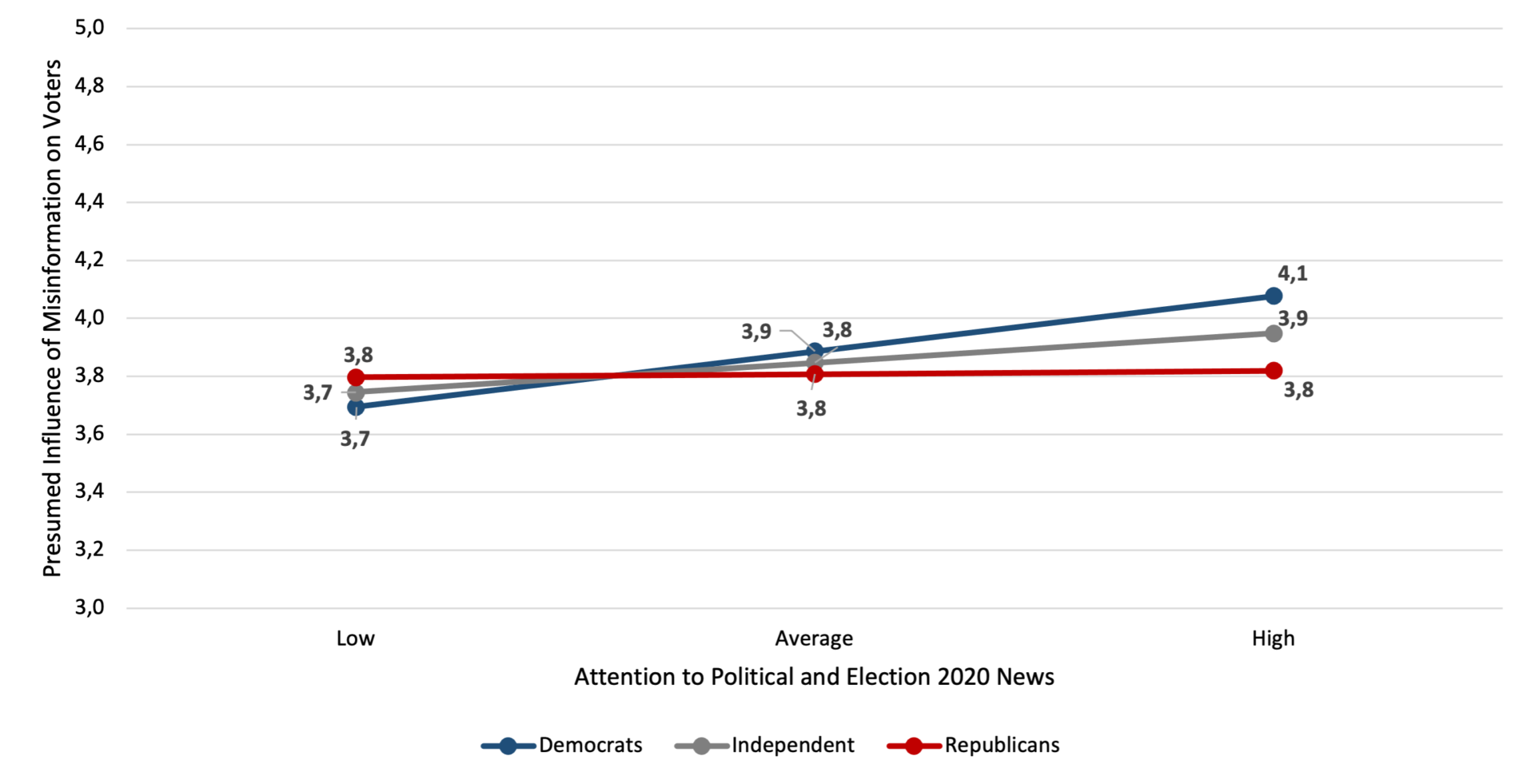

Greater attention to news and information about American politics and the 2020 election is associated with greater PIM on other voters among self-identified Democrats (b =.13, p < .001) and Independents (b = .07, p < .001) (see Appendix A in Supplementary Materials). In contrast, there is no significant relationship between attention to political news and information and presumed influence of misinformation on other voters among Republicans. Figure 1 graphs the marginal mean of PIM on other voters at low, mean, and high levels of attention separately for self-identified Democrats, Independents, and Republicans. Among those who pay higher attention to news about politics and the 2020 election, Democrat respondents on average rate the presumed influence on other voters about 6.8% higher than Republican survey respondents after controlling for all other variables in the analysis.

Finding 2: Presumed influence of political misinformation on other voters decreases satisfaction with American electoral democracy regardless of political party identification.

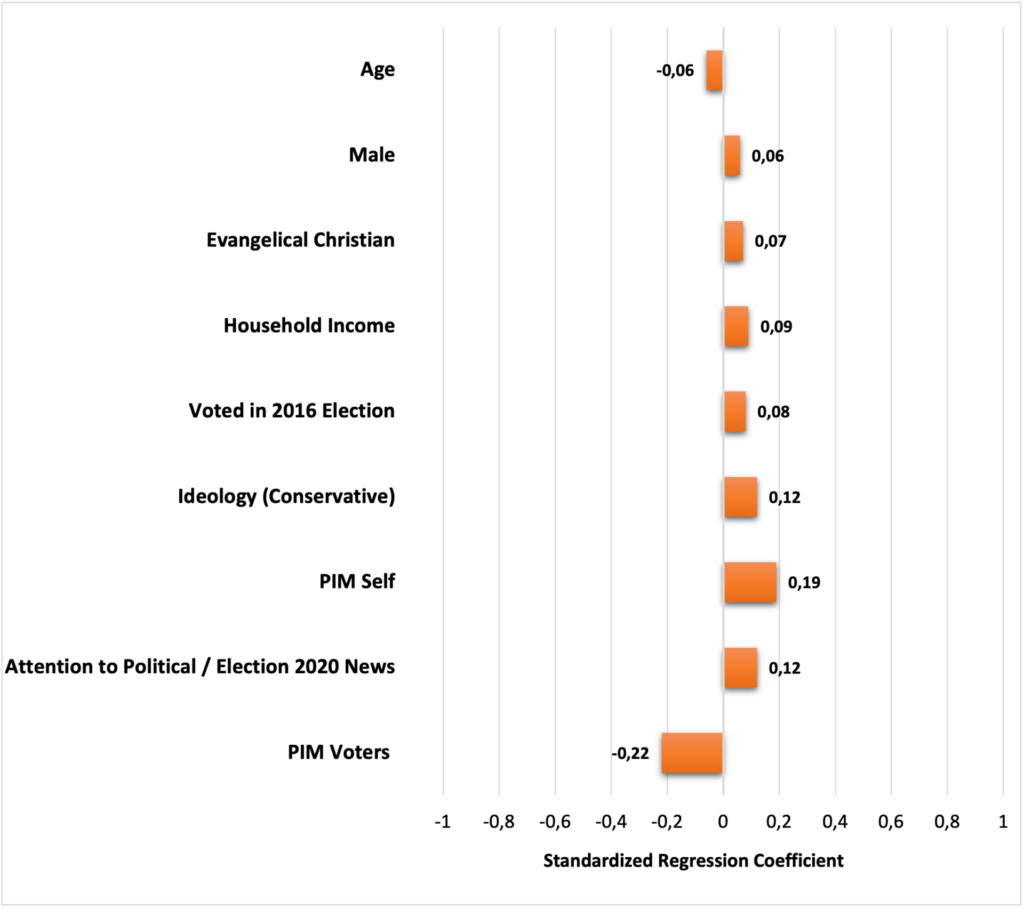

In turn, PIM on other voters erodes the virtuous circle of political news and American democracy. We tested the association between attention to political and 2020 election news and PIM on other voters controlling for several covariates including PIM on oneself. The significant associations presented in Figure 2 (see Supplementary Materials for full OLS regression model). On average, greater attention to political and 2020 election news is associated with greater satisfaction with electoral democracy, a key component of the virtuous circle (b = .12, p < .001). On the other hand, presumed influence of misinformation on other voters is associated with significantly less satisfaction with electoral democracy (b = –.22, p < .001), accounting for nearly five percent (4.7%) of the unique variance in satisfaction with democracy. These results hold true equally for Democrats, Independents, and Republicans alike, as the analysis showed no significant variation in either set of relationships by political partisanship.

Finding 3: Attention to political news indirectly reduces democratic satisfaction among Democrats and Independents through the presumed influence of misinformation.

Though attention to news and information is directly associated with greater democratic satisfaction among Americans of all political stripes, we tested its indirect relationship with democratic satisfaction through PIM on others. Our analysis of indirect effects showed that greater attention to news about the 2020 election and politics significantly reduces democratic satisfaction among Democrats (b = -.08, p < .001, LLCI = -.12, ULCI = -.04) and Independents (b = -.04, p < .001, LLCI = -.08, ULCI = -.01), but not Republicans, by increasing PIM on others among these segments of the American body politic.

In sum, though attention to news and information about American politics and the election is associated with greater satisfaction with electoral democracy consistent with the virtual circle hypothesis, our findings highlight how political misinformation may simultaneously harm this process. Political misinformation pollutes American political news and discourse as attention to news heightens its presumed influence on other voters, especially among Democrats and Independents. In turn, this PIM on other voters, regardless of one’s partisan identity, is significantly associated with less democratic satisfaction.

Methods

Survey data was collected using a commercial, online, opt-in survey panel with 2,474 respondents (after omitting incomplete responses, final analyses were conducted on all 2,423 respondents) between March 6 and March 19, 2020, during the Democratic Party Presidential primaries. Quota samples were used to match sample demographics to the U.S. general population based on gender, age, race, ethnicity, and educational attainment to ensure sample heterogeneity (see Appendix A for sample demographic information and comparison with the general population). Only respondents who successfully passed several cognitive attention checks embedded within the survey instrument were included in the final sample.

Beyond socio-demographic and control variables, four focal independent variables were measured for our analysis (see Appendix A in Supplementary Materials for detailed question wording and measurement details). Political partisanship was assessed by a standard scale asking party identification. Attention to news and information about politics and the 2020 election was measured by combining two separate survey items asking respondents how closely they follow news about a) politics in general and the b) 2020 election.

The presumed influence of political misinformation was assessed by asking respondents their level of agreement with two parallel batteries of five Likert survey statements about the influence of false or misleading news stories on a) themselves and b) other voters. Statements were crafted based on previous work measuring presumed influence of misinformation and media more generally (Rojas et al., 1996; Baek et al., 2019). To increase generalizability of the measure we employed a version of stimulus sampling (see Wells & Windschitl, 1999) where respondents were randomly assigned to one of five different question wordings asking them to assess the presumed influence of misinformation on themselves and other voters from either: a) domestic sources b) foreign sources, c) liberal sources, d) conservative sources, e) no source given. Dummy codes indicating which version of the question wording respondents received were entered into all analyses with the no-source-given wording as the reference category. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no significant variance in electoral democratic satisfaction across question wording. Respondents’ agreement with the statements was averaged to create two scales of presumed influence of misinformation on oneself and others.

Previous research on assessing democratic satisfaction has defined the concept as comprising two components, an evaluation of how democratic a country’s politics is and an individual’s level of satisfaction with how democracy works in the country more generally (Mattes & Bratton, 2007). Therefore, our outcome variable, satisfaction with American electoral democracy, was created by averaging three survey items asking respondents how democratic or undemocratic politics is in the United States today, their satisfaction with the 2020 electoral process, and their satisfaction with the way democracy is working in the United States today.

We evaluated our hypotheses employing PROCESS, a SPSS mini-program developed to test for moderation and mediation using serial ordinary least square (OLS) regressions that test the statistical association between our predictor and outcome variables controlling for other observable variables that we measured on the survey (Hayes, 2018). PROCESS allows us to estimate the relationship between attention to news about the 2020 election and politics and the presumed influence of misinformation at differing levels of political partisanship. It also allows us to estimate the direct and indirect effect of news attention and the direct effect of presumed influence on other voters on satisfaction with electoral democracy. Our analysis allows us to describe and estimate the strength of relationships between our predictor and outcome variables, but we are not able to make strong claims on causal direction.

We hypothesized that attention to news and information about politics and the 2020 election would increase the presumed influence of misinformation on other voters, controlling for the presumed influence on oneself. This hypothesis was partially supported, as attention to politics and the 2020 election was positively associated with the presumed influence on voters among Democrats and independents, but not Republicans. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between attention to news about politics and the 2020 election and PIM on other voters at differing levels of partisanship. The full estimation results can be found in Table B1 in Supplementary Materials Appendix B.

We also hypothesized that presumed influence of misinformation on other voters would be significantly associated with less satisfaction with electoral democracy. This hypothesis was supported. Figure 2 presents the coefficients for the model predicting satisfaction with electoral democracy including several control variables. The full estimation results can be found in Table B2 in Supplementary Materials Appendix B.

Our last hypothesis was that although attention to news and information about politics and the election may directly increase satisfaction with electoral democracy, it may indirectly decrease electoral satisfaction with democracy by increasing the PIM on other voters. Our hypothesis was partially supported. Attention to news and information about the 2020 election and politics was directly associated with increased democratic satisfaction and indirectly associated with decreased democratic dissatisfaction among Democrats and Independents. The full estimation results can be found in Table B2 in Supplementary Materials Appendix B.

Limitations

There are three major limitations to our methodological approach. The cross-sectional design of our study could not fully test the causal process by which attention to electoral and political news and presumed influence of misinformation influence respondent satisfaction with electoral democracy. Additional longitudinal or experimental work is needed to confirm our results. The sample used for our study, while it did approximate the demographics of the U.S. general population, is based on panels managed by the firm Qualtrics. Respondents, therefore, choose to take part in the panel and may have characteristics different from the U.S. population as a whole. Though we make the argument that PIM on others may hurt satisfaction with electoral democracy in democracies in general, we test our argument only in a single country case study. However, we believe the same psychological processes outlined in this study are generalizable across democratic contexts where there is a high level of concern about the influence of misinformation as there is in many democracies globally (CIGI-Ipsos, 2019; Lloyd’s Register Foundation, 2020).

Topics

Bibliography

Baek, Y. M., Kang, H., & Kim, S. (2019). Fake news should be regulated because it influences both “others” and “me”: How and why the influence of presumed influence model should be extended. Mass Communication and Society, 22(3), 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2018.1562076

Bail, C. A., Guay, B., Maloney, E., Combs, A., Hillygus, S., Merhout, F., Freelon, D., & Volfovsky, A. (2020). Assessing the Russian Internet Research Agency’s impact on the political attitudes and behaviors of American Twitter users in late 2017. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(1), 243–350. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1906420116

Cho, Y., & Kim, Y. C. (2016). Procedural justice and perceived electoral integrity: The case of Korea’s 2012 presidential election. Democratization, 23(7), 1180–1197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1063616

CIGI-Ipsos. (2019). 2019 CIGI-Ipsos global survey on internet security and trust. Centre for International Governance Innovation. https://www.cigionline.org/internet-survey-2019

Erlingsson, G. Ó., Linde, J., & Öhrvall, R. (2014). Not so fair after all? Perceptions of procedural fairness and satisfaction with democracy in the Nordic welfare states. International Journal of Public Administration, 37(2), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2013.836667

Guess, A. M., Lerner, M., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., Sircar, N. (2020). A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and false news in the United States and India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 27, 15536–15545. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920498117

Gunther, A. C., & Storey, J. D. (2003). The influence of presumed influence. Journal of Communication, 53(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb02586.x

Gunther, R., Beck, P. A., & Nisbet, E. C. (2019, October). “Fake news” and the defection of 2012 Obama voters in the 2016 Presidential election. Electoral Studies, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.03.006

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications.

Ho, S. S., Goh, T. J., & Leung, Y. W. (2020). Let’s nab fake science news: Predicting scientists’ support for interventions using the influence of presumed media influence model. Journalism, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1464884920937488

Kelly, S., Truong, M., Shahbaz, A., Earp, M., & White, J. (2017). Freedom on the net 2017: Manipulating social media to undermine democracy. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2017/manipulating-social-media-undermine-democracy

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. Plenum Press.

Lind, E. A., Kanfer, R., & Earley, P. C. (1990). Voice, control, and procedural justice: Instrumental and noninstrumental concerns in fairness judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 952. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.952

Lloyd’s Register Foundation. (2020). The Lloyd’s Register Foundation World Risk Poll. https://wrp.lrfoundation.org.uk/explore-the-poll/

Magalhães, P. C. (2016). Economic evaluations, procedural fairness, and satisfaction with democracy. Political Research Quarterly, 69(3), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912916652238

Mattes, R., & Bratton, M. (2007). Learning about democracy in Africa: Awareness, performance, and experience. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 192–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00245.x

McLeod, D. M., Detenber, B. H., & Eveland, Jr., W. P. (2001). Behind the third‐person effect: Differentiating perceptual processes for self and other. Journal of Communication, 51(4), 678–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2001.tb02902.x

Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., Stocking, G., Walker, M., & Fedeli, S. (2019, June 5). Many Americans say made-up news is a critical problem that needs to be fixed. Pew Research Center: Journalism & Media. https://www.journalism.org/2019/06/05/many-americans-say-made-up-news-is-a-critical-problem-that-needs-to-be-fixed/

Mueller, J. (2006). Overblown: How politicians and the terrorism industry inflate national security threats, and why we believe them. Free Press.

Norris, P. (2000). A virtuous circle: Political communications in postindustrial societies. Cambridge University Press.

Norris, P. (2019). Do perceptions of electoral malpractice undermine democratic satisfaction? The US in comparative perspective. International Political Science Review, 40(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512118806783

Rojas, H., Shah, D. V., & Faber, R. J. (1996). For the good of others: Censorship and the third-person effect. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 8(2), 163–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/8.2.163

Tal-Or, N., Cohen, J., Tsfati, Y., & Gunther, A. C. (2020). Testing causal direction in the influence of presumed media influence. Communication Research, 37(6), 801–824. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650210362684

Tyler, T. R., Rasinski, K. A., & Spodick, N. (1985). Influence of voice on satisfaction with leaders: Exploring the meaning of process control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.72

Vraga, E. K., & Tully, M. (2019). News literacy, social media behaviors, and skepticism toward information on social media. Information, Communication & Society, 24(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1637445

Wells, G. L., & Windschitl, P. D. (1999). Stimulus sampling and social psychological experimentation. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin, 25(9), 1115–1125.

Zimmerman, F., & Kohring, M. (2020). Mistrust, disinforming news, and vote choice: A panel survey on the origins and consequences of believing disinformation in the 2017 German parliamentary election. Political Communication, 37(1) 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1686095

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by Ohio State University.

Competing Interests

There are no competing or conflict of interests among any of the authors.

Ethics

The study’s research protocol was approved by the Ohio State University institutional review board for socio-behavioral research. Human subjects provided informed consent to participate in the survey.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

Survey question wording, SPSS file of data employed in the analyses, and associated SPSS syntax file is available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QMEBYZ