Peer Reviewed

#SaveTheChildren: A pilot study of a social media movement co-opted by conspiracy theorists

Article Metrics

0

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

Page Views

In a preliminary analysis of 121,984 posts from X (formerly known as Twitter) containing the hashtag #SaveTheChildren, we found that conspiratorial posts received more engagement than authentic hashtag activism between January 2022 and March 2023. Conspiratorial posts received twice the number of reposts as non-conspiratorial content. Our initial findings of a forthcoming larger multi-platform study suggest that the way that users strategically exploit the #SaveTheChildren hashtag may have implications for the visibility of legitimate social movements on the X platform. Future work should consider other social media platforms to determine if the visibility of legitimate social movements is decreasing more broadly, particularly in the context of 2024 being the largest election year in history.

Research Question

- How are authentic social movements being impacted by conspiracy theories engaging in hashtag hijacking on X?

Essay Summary

- One of the QAnon conspiracy theory’s first significant actions on X (formerly known as Twitter) was to co-opt the hashtag #SaveTheChildren from the charity of the same name to promote baseless conspiracy theories of a child sex trafficking ring.

- We analyzed #SaveTheChildren as a pilot study that may be exemplary of the contention between authentic social movements and conspiratorial content more broadly.

- We observed that #SaveTheChildren was being utilized for both conspiratorial purposes and as part of hashtag activism, but conspiratorial content was reposted at twice the rate of non-conspiratorial content.

- In our dataset, #SaveTheChildren was used more frequently in support of conspiracy theories than in hashtag activism for social advocacy movements.

- Future work should consider the role of hashtag hijacking in the amplification of conspiracy theories and conduct wider-scale investigations of how the strategic affordances of social media platforms are leveraged in spreading conspiratorial content and misinformation.

Implications

This preliminary investigation considered the hashtag #SaveTheChildren, which provided a case study for the contention we have observed between activism and conspiratorial content on X. Our study provides an initial contribution to a growing body of literature on hashtag hijacking by quantitatively and qualitatively analyzing the prevalence of conspiratorial content compared with authentic social activism in the conversation around #SaveTheChildren on X. Hashtag hijacking is defined as: “[using] a trending hashtag to promote topics that are substantially different from its recent context” (VanDam & Tan, 2016, p. 370) or “to promote one’s own social media agenda” (Darius & Stephany, 2019, p. 1). We noted prevalent discourse around humanitarian and public health issues. In our dataset, #SaveTheChildren is most frequently associated with (1) posts relating to charities seeking aid for children experiencing violence or in areas of geopolitical tension and (2) posts relating to COVID-19 vaccines and conspiratorial views on their impact on children’s health. The former action of raising awareness is often described as hashtag activism, an act of mobilizing support for social movements online and can result in reshaping of social norms offline (Mousavi & Ouyang, 2021; Goswami, 2018).

We observed that conspiratorial posts containing #SaveTheChildren in the dataset were more likely to be engaged with than social activism posts. The hashtag gained mainstream recognition for its association with QAnon in 2020 when it was co-opted from the legitimate charity Save The Children and widely used on Facebook and Twitter (Buntain et al., 2022; Fagan, 2020; Roose, 2020). The QAnon conspiracy theory proposes that a cabal of Satanic, cannibalistic elites are operating a sex trafficking ring, against which former president Donald Trump was alleged to be working (Roose, 2021; Wong, 2020). QAnon proponents use this hashtag to raise awareness of the perceived plot to traffic and harm children, though there is no widely accepted evidence of this alleged cabal. #SaveTheChildren is a case of hashtag activism being utilized negatively, as the original intent of the hashtag has been altered and resulted in increased exposure of users to conspiratorial content, some of which relates to public health.

In answering our research question, we explore how the #SaveTheChildren dataset could be representative of wider implications for social media platforms when hashtags are utilized for both legitimate and conspiratorial purposes. In 2020, Facebook blocked #SaveTheChildren due to “low quality content” (Dickson, 2020, para. 3). #SaveTheChildren is not the only hashtag that can contain a mix of legitimate and conspiratorial content. In the face of emergency events, seemingly benign hashtags—such as those relating to natural disasters or elections—can become a melting pot of announcements from authorities, breaking news, and conspiratorial speculation around the event (Mousavi & Ouyang, 2021; Xanthopoulous et al., 2016). As researchers, we are concerned about the public health implications of being unable to access accurate information in situations like unfolding political tensions, vaccination rollouts, or emergency situations, and our preliminary findings indicate further research is needed in this space.

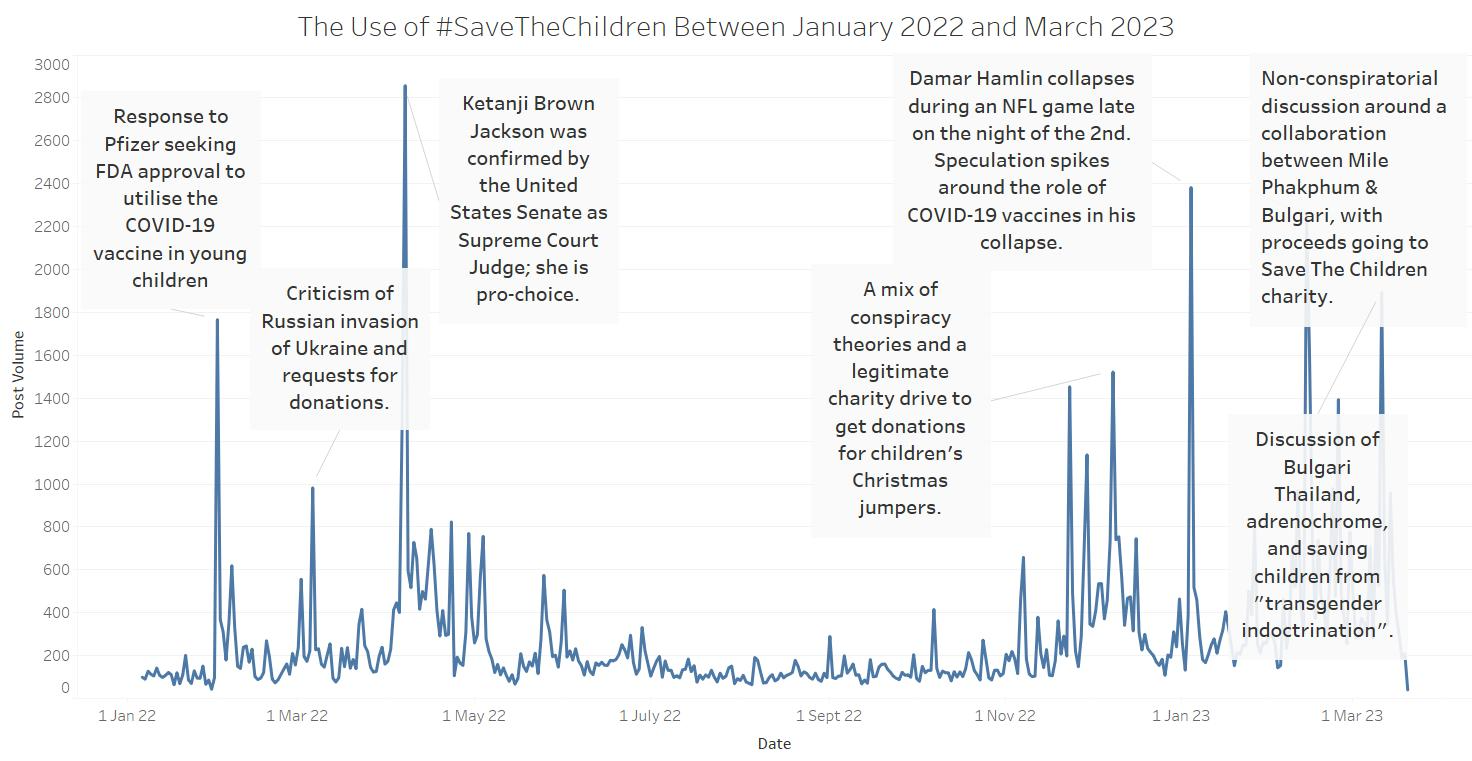

In our preliminary study, we found that conspiratorial #SaveTheChildren posts were amplified at a greater rate and more effectively than posts using the hashtag for activist and/or organizational purposes. This aligns with research from Vosoughi et al. (2018), who found that false news stories spread more quickly and widely than factual news stories. In periods of geopolitical conflict and political tension, there is an increased frequency of #SaveTheChildren for both conspiratorial and legitimate purposes (see Figure 2). The implications of these findings are particularly poignant in 2024, which is the largest election year in history with almost 50% of the global population voting in elections (Ewe, 2023; Shamim & Lodhi, 2024). X users turn to social media for discussion of political events and to inform themselves of electoral proceedings. In the 2020 U.S. presidential election, voters were faced with misinformation surrounding poll locations, mail-in ballot procedures, and voting machines (Hsu, 2022; Ingram, 2020; Rutenberg & Conger, 2024; Sanderson et al., 2021). As such, it is critical that research on conspiratorial hijacking of hashtags continues prior to the 2024 elections to avoid further spread of misinformation.

Evidence

Finding 1: The hashtag #SaveTheChildren is utilized to spread more conspiratorial content than authentic activist content in the dataset.

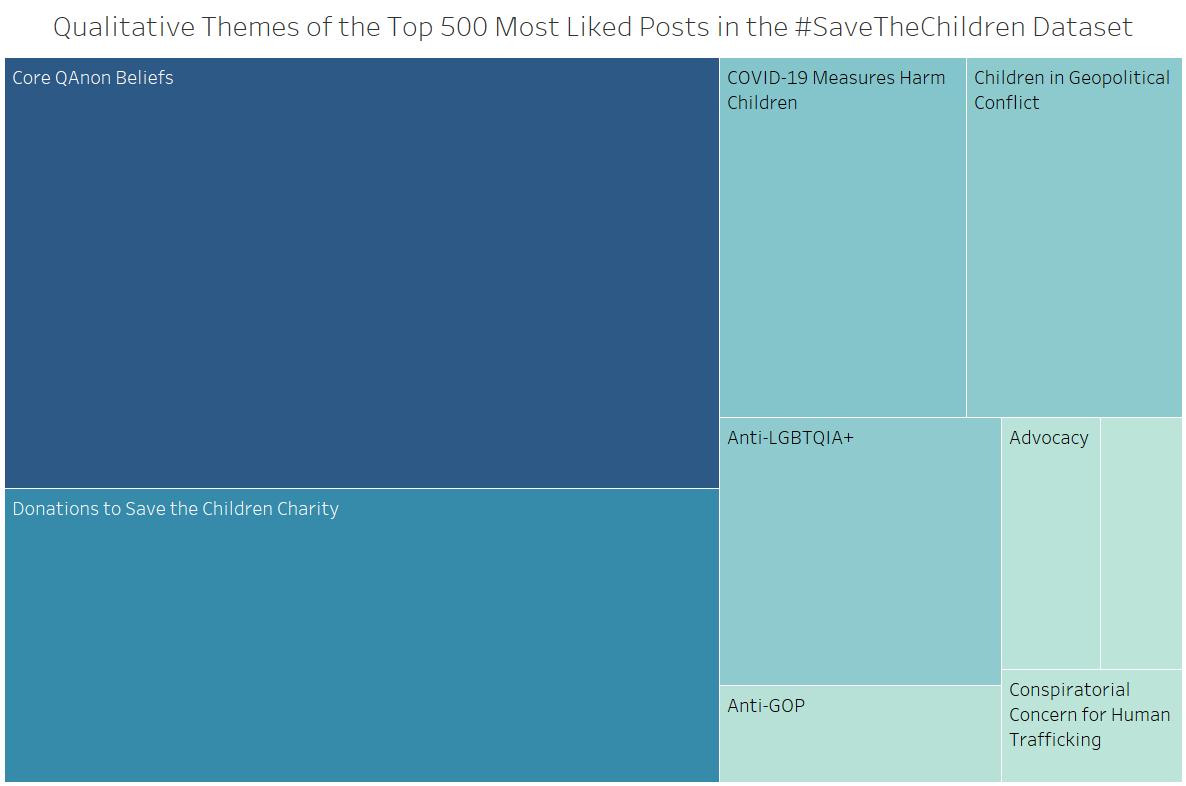

Our analysis revealed that #SaveTheChildren is more often used in relation to conspiracy theories than genuine activism on X, in our qualitative consideration of the top 500 posts in the dataset. By conducting a preliminary analysis on the 500 most-liked posts, we identified a frequent use of #SaveTheChildren in conspiratorial narratives. As demonstrated in Figure 1, posts with the theme core QAnon beliefs occurred most frequently in this subset of the data (see Appendix 1). The second most frequent theme was donations to the Save The Children charity, which contains posts supporting the charity. However, many of the other qualitative themes contain conspiratorial content and misinformation that goes beyond the QAnon conspiracy theory to anti-vaccination and anti-LGBTQIA+ rhetoric. These preliminary findings show the potential for #SaveTheChildren, QAnon, and other hijacked hashtags to spread outside the initial confines of a conspiracy theory into other discussions and mainstream communication.

Finding 2: Conspiratorial posts were reposted more often than non-conspiratorial posts and more effectively amplified on X.

While conspiratorial and non-conspiratorial content received a similar number of likes—both per post and across the dataset—the conspiratorial content received greater amplification through reposts. The pattern of increased retweets and engagement with conspiracy theories and misinformation is reflected in previous scholarship (e.g., Lewandowsky & van der Linden, 2021; Swire-Thompson & Lazer, 2020; Vosoughi et al., 2018). The statistical outliers in the dataset—i.e. the posts that received more reposts than average or went “viral”—were also more likely to be conspiratorial. Further research should be conducted across different datasets and social media platforms to determine the replicability of this finding.

Finding 3: Increased conspiratorial content has the potential to impact legitimate social movements on X.

While there is legitimate activism on X utilizing #SaveTheChildren, our preliminary findings show this content can be obscured by increasing volumes of conspiratorial content. Conspiratorial posts in this dataset received an average of 458 reposts (median = 66) compared to 229 for non-conspiratorial posts (median = 44). This imbalance in visibility makes it difficult for casual observers of an issue to determine what is factually correct and what is conspiratorial. Should this trend continue across other hashtags, the potential for impact on upcoming elections in 2024 is of particular interest for further work.

Finding 4: Hashtag hijacking of #SaveTheChildren allows more X users to be exposed to conspiratorial content.

We found extensive overlap in usage between #SaveTheChildren and other hashtags that promote anti-vaccination stances. One of the implications of this overlap is that people who are otherwise not engaged in conspiracy theories can easily be exposed through the #SaveTheChildren hashtag. Following the collapse of NFL player Damar Hamlin after a tackle during a game due to commotio cordis (Hagen, 2023), #SaveTheChildren increasingly began co-occurring with anti-vaccination hashtags such as #DiedSuddenly, which proposes that COVID-19 vaccines are causing widespread cardiac arrests amongst children and young people. Activists who are using the hashtag to discuss the charity of the same name may inadvertently be exposed to content that is conspiratorial in nature and undermines public health recommendations.

Methods

In this note, we have preliminarily considered how authentic social movements can be impacted by conspiracy theories on the platform X. The hashtag #SaveTheChildren was chosen as an initial case study in a forthcoming multi-platform study as it serves as an entry point to determine whether this hashtag, and potentially conspiracy theories more broadly, are impacting social movements on X. When used conspiratorially rather than for genuine activism, #SaveTheChildren is often associated with QAnon content. Previous academic work and numerous news articles have outlined the connection between #SaveTheChildren and QAnon; we were confident based on this literature and a preliminary search of the hashtag on X that it would be appropriate for inclusion in our larger study (e.g., Buntain et al., 2022; Fagan, 2020; Moran & Prochaska, 2023; Roose, 2020).

We addressed our research question using a dataset of posts collected from Twitter (now known as X) containing the hashtag #SaveTheChildren. To collect these posts, we used the Twitter API v2 for Academic Research, specifically the twarc2 Python library for data collection. Python was also used for data analysis and the software Tableau for visualization. The API is no longer freely available as X has transitioned to a paid-tier API system since the time of data collection. We collected 121,984 tweets containing the hashtag, including 44,494 unique tweets, between January 6, 2022, and March 20, 2023. There is a difference between the total tweets and unique tweets as a significant portion of our dataset comprised reposts. The data collection period was chosen for several reasons: to gain at least a year of data, include various significant global events such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and ensure the dataset was within our allocated number of tweets provided by the Twitter API. We chose the anniversary of the January 6 insurrection as a starting point to meet the above requirements whilst also capturing any potentially relevant discussion on this date, as conspiracy theories continue to swirl around the insurrection (Jackman et al., 2024).

Given that the top 500 most retweeted posts account for 84.7% of all retweets in our dataset, we focused on this subset of the data to qualitatively analyze. In our dataset, the majority (75.4%) of posts received zero retweets. A further 20.8% of posts in our dataset received one to five retweets. Only a small fraction of posts in our dataset received more than ten retweets (2.3% of posts), which is representative of repost distributions on X and social media more broadly (Lu et al., 2014; Remy et al., 2013).

The authors extracted the top 500 most-liked tweets and qualitatively coded them. Coding was completed separately with the authors conferring after the coding had been completed to ensure intercoder reliability. We found five hundred tweets sufficient to code to saturation. The collected posts were temporally analyzed to show changes in activity during data collection. Qualitative coding was necessary to capture the nuance of the use of #SaveTheChildren and whether posts represented genuine activism or conspiratorial content. The qualitative codebook can be found in Appendix 1.

Topics

Bibliography

Buntain, C., Johns, M., Deal Barlow, M., & Bloom, M. (2022). Paved with bad intentions: QAnon’s Save the Children campaign. Journal of Online Trust and Safety, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.54501/jots.v1i2.51

Darius, P., & Stephany, F. (2019). Twitter ‘hashjacked’: Online polarisation strategies of Germany’s political far-right. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/6gbc9

Dickson, E. (2020, August 12). What is #SaveTheChildren and why did Facebook block it? Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/savethechildren-qanon-pizzagate-facebook-block-hashtag-1041812/

Ewe, K. (2023, December 28). Elections around the world in 2024. Time. https://time.com/6550920/world-elections-2024/

Fagan, K. (2022, March 23). #SaveTheChildren: How a fringe conspiracy theory fueled a massive child abuse panic. The Media Manipulation Casebook. https://mediamanipulation.org/case-studies/savethechildren-how-fringe-conspiracy-theory-fueled-massive-child-abuse-panic

Goswami, M. (2018). Social media and hashtag activism. In S. Bala (Ed.), Liberty dignity and change in journalism (pp. 252–262). Kanishka Publishers.

Hagen, L. (2023, January 10). How Damar Hamlin’s collapse fueled anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/01/10/1147969504/how-damar-hamlins-collapse-fueled-anti-vaccine-conspiracy-theories

Hsu, T. (2022, November 9). Elon Musk’s Twitter did not perform at its best on election day. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/09/technology/elon-musk-twitter-maricopa-election-false-claims.html

Ingram, D. (2020, October 26). Twitter launches ‘pre-bunks’ to get ahead of voting misinformation. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/twitter-launches-pre-bunks-get-ahead-voting-misinformation-n1244777

Jackman, T., Clement, S., Guskin, E., & Hsu, S. S. (2024, January 8). A quarter of Americans believe FBI instigated Jan. 6, Post-UMD poll finds. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2024/01/04/fbi-conspiracy-jan-6-attack-misinformation/

Lewandowsky, S., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Countering misinformation and fake news through inoculation and prebunking. European Review of Social Psychology, 32(2), 348–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2021.1876983

Lu, Y., Zhang, P., Cao, Y., Hu, Y., & Guo, L. (2014). On the frequency distribution of retweets. Procedia Computer Science, 31, 747–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2014.05.323

Moran, R. E., & Prochaska, S. (2023). Misinformation or activism? Analyzing networked moral panic through an exploration of #SaveTheChildren. Information, Communication & Society, 26(16), 3197–3217. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2146986

Mousavi, P., & Ouyang, J. (2021). Detecting hashtag hijacking for hashtag activism. In A. Field, S. Prabhumoye, M. Sap, Z. Jin, J. Zhao, & C. Brockett (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1st workshop on NLP for positive impact (pp. 82–92). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2021.nlp4posimpact-1.9

Remy, C., Pervin, N., Toriumi, F., & Takeda, H. (2013). Information diffusion on Twitter: Everyone has its chance, but all chances are not equal. In 2013 International Conference on Signal-Image Technology & Internet-Based Systems (pp. 483–490). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/SITIS.2013.84

Roose, K. (2020, August 12). QAnon followers are hijacking the #SaveTheChildren movement. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/12/technology/qanon-save-the-children-trafficking.html

Rutenberg, J., & Conger, K. (2024, January 25). Elon Musk is spreading election misinformation, but X’s fact checkers are long gone. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/25/us/politics/elon-musk-election-misinformation-x-twitter.html

Sanderson, Z., Brown, M. A., Bonneau, R., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. A. (2021). Twitter flagged Donald Trump’s tweets with election misinformation: They continued to spread both on and off the platform. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-77

Shamim, A., & Lodhi, S. (2024, January 4). The year of elections – Is 2024 democracy’s biggest test ever? Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/4/the-year-of-elections-is-2024-democracys-biggest-test-ever

Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2020). Public health and online misinformation: Challenges and recommendations. Annual Review of Public Health, 41(1), 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094127

VanDam, C., & Tan, P.-N. (2016). Detecting hashtag hijacking from Twitter. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Web Science (pp. 370–371). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2908131.2908179

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Wong, J. C. (2020, August 25). QAnon explained: The antisemitic conspiracy theory gaining traction around the world. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/aug/25/qanon-conspiracy-theory-explained-trump-what-is

Xanthopoulos, P., Panagopoulos, O. P., Bakamitsos, G. A., & Freudmann, E. (2016). Hashtag hijacking: What it is, why it happens and how to avoid it. Journal of Digital & Social Media Marketing, 3(4), 353–362.

Funding

Timothy Graham received funding from the Australian Research Council for his Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE220101435), “Combatting Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour on Social Media.”

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The research protocol employed in this research project was approved by the Queensland University of Technology ethics committee for low-risk human ethics applications (project number DE220101435). Human subjects did not provide informed consent.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AIBDZT