Peer Reviewed

Research note: Examining false beliefs about voter fraud in the wake of the 2020 Presidential Election

Article Metrics

68

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

The 2020 U.S. Presidential Election saw an unprecedented number of false claims alleging election fraud and arguing that Donald Trump was the actual winner of the election. Here we report a survey exploring belief in these false claims that was conducted three days after Biden was declared the winner. We find that a majority of Trump voters in our sample – particularly those who were more politically knowledgeable and more closely following election news – falsely believed that election fraud was widespread, and that Trump won the election. Thus, false beliefs about the election are not merely a fringe phenomenon. We also find that Trump conceding or losing his legal challenges would likely lead a majority of Trump voters to accept Biden’s victory as legitimate, although 40% said they would continue to view Biden as illegitimate regardless. Finally, we found that levels of partisan spite and endorsement of violence were equivalent between Trump and Biden voters.

Research Questions

- In the run-up to the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election, false statements about alleged election fraud – particularly with respect to mail-in voting – have been widespread. Using a survey fielded immediately after the election was called in favor of Biden, we investigate the extent to which voters held false beliefs about voter fraud and the election outcome, as well as the potential consequences of such false beliefs.

- What factors might lead Trump voters to accept Biden as the next President of the United States?

- What do people expect that they would do if Biden is inaugurated and Trump does not concede?

- What characteristics are correlated with holding false beliefs about the election and voter fraud among Trump and Biden voters?

Research note Summary

- In a survey run on November 10th, three days after the election was called in favor of Biden by mainstream media outlets, we asked 617 Trump voters and 1,036 Biden voters (quota-matched to the national distribution on age, gender, ethnicity, and region) about their beliefs related to the election.

- Despite a lack of any meaningful evidence of systemic election fraud, a majority of Trump voters believed that fraud is common in U.S. elections (>77%), and that Trump won the 2020 election (>65%).

- Although only 22% of Trump voters believed Biden’s win to be legitimate at the time of the survey, another 21% said they would be convinced of Biden’s legitimacy either by Trump losing his legal challenges or by Trump conceding, another 6% would be convinced by Trump losing his legal challenges but not by him conceding, and another 11% would be convinced by Trump conceding but not by him losing his legal challenges. The final 40% of Trump voters said they would remain unconvinced of the legitimacy of Biden’s win in either case.

- Partisan spite and endorsement of political violence were equivalent between Trump and Biden voters, and rejected by a majority of voters for both candidates. Most Trump voters (88%) also indicated that they would not protest if Trump does not concede and Biden is nonetheless inaugurated as President. Trump voters who were more politically knowledgeable and focused on election news held more false beliefs, whereas those who were more reflective had more accurate beliefs.

Implications

For months leading up to the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election, false claims about potential voter fraud have been common on the political right (Lytvynenko & Silverman, 2020a; Zadrozny, 2020a). These claims only seemed to increase once Donald Trump’s early lead on election night started to decrease as mail-in ballots were counted, ultimately leading the election to be called in Biden’s favor several days later (Lytvynenko & Silverman, 2020b; Zadrozny, 2020b). Trump himself was responsible for dozens of false and misleading claims about the prevalence of election fraud in the U.S. and the outcome of the 2020 election in the days preceding this survey (Funke et al., 2020; Kessler & Rizzo, 2020). Examples included false claims that voting machines fraudulently switched votes to Biden, that large numbers of Trump ballots were destroyed, and that Republican election officials were unduly restricted from observing polling stations (leading to malfeasance). Furthermore, although the “news” branch of Fox News followed other mainstream media outlets and called the election for Biden, several of the hosts in the “opinion” branch of Fox News (such as Sean Hannity) parroted Trump’s false election fraud claims (Darcy, 2020) as did news sources further on the right (e.g., Breitbart, Newsmax, One America News Network). As of this writing, no evidence for systemic election fraud has been produced and the various legal challenges have all been rejected by courts (Williams, 2020). Thus, these false claims constitute misinformation – that is, as information that is false, inaccurate, or misleading (Wardle, 2018).

Here, we investigate the extent to which voters believe these false claims about election fraud and, more importantly, about who won the 2020 election. To shed some light on this question, we conducted a survey run on November 10th, three days after the election was called for Biden by all major news organizations. Consistent with other contemporary polls (Bump, 2020; Laughlin & Shelburne, 2020; Mitchell, Jurkowitz, Oliphant, & Shearer, 2020; but see Kahn, 2020), we found that false beliefs about election fraud and a Trump victory were widespread among Trump voters. We also found that a majority of Trump voters would view Biden as legitimate if Trump loses his various court challenges and/or concedes the election (although a strong minority – 40% – would continue to view Biden as illegitimate regardless). Moreover, few voters on either side expressed high levels of partisan spite or endorsement of political violence, although of course it only takes a few individuals with a willingness to engage in violence to have a very large negative impact.

Interestingly, we find that Trump voters with higher levels of basic political knowledge and engagement with election news were more likely to hold false beliefs about the election, while the opposite was true of Biden voters. Yet analytic thinking was associated with more accurate beliefs about the election outcome among Trump voters. These results speak to the ongoing debate about whether cognitive sophistication is associated with increased political polarization (Kahan, 2013; Kahan et al., 2017) or increased accuracy (Pennycook & Rand, 2019b), highlighting to need to differentiate between political knowledge and analytic thinking per se.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, our sample of Trump voters was comparatively small – although reassuringly, a similar survey we conducted the day before the election was called for Biden (not reported here for brevity) showed very similar results. Second, we used a quota-based sample rather than a probability sample (i.e., our sample is matched to national demographics on some factors, rather than being truly representative); and more generally, the poor performance of 2020 election polls has raised issues with non-representativeness in survey respondents. Our sample may be missing a segment of particularly strong Trump supporters who avoid surveys. Third, responses to some of our questions (e.g., about political violence) may be muted by social desirability concerns – although it is also possible that Trump’s rhetoric may have made his supporters less shy about violating previously-hold norms (e.g., Clayton et al., 2020).

Of course, our data do not test whether our participants’ false beliefs about the election were caused by misinformation per se, versus being a feature of political polarization more generally. Indeed, prior work shows that people often view the opposing candidate as illegitimate (albeit not as levels as extreme as reported here) (Edelson et al., 2017). Be that as it may, the extremely common false beliefs that we report are deeply concerning, and unlikely to go away any time soon.

Findings

Beliefs about election fraud are very prevalent among Trump voters

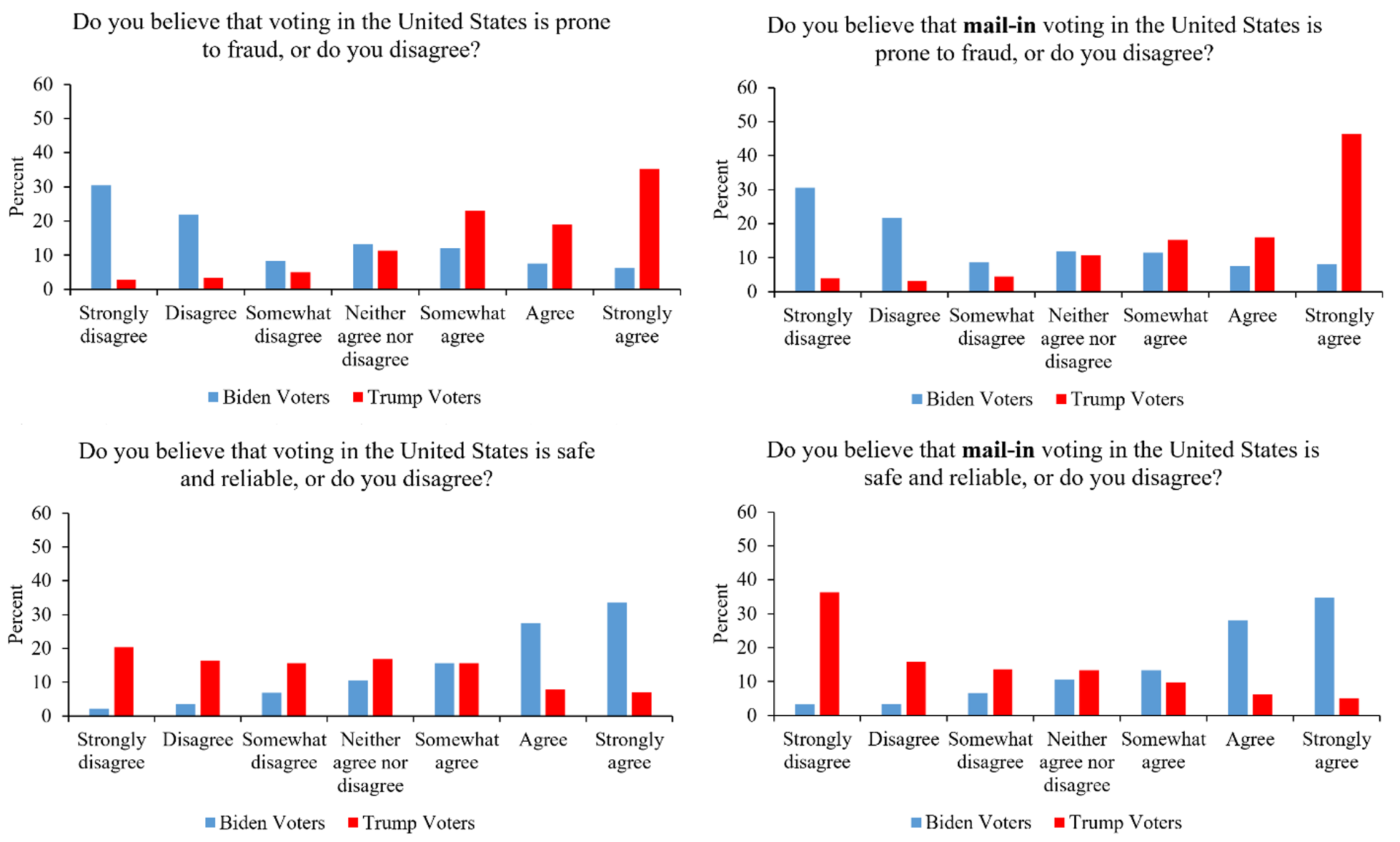

In our sample of 617 Trump voters and 1,036 Biden voters, we found a high prevalence of skepticism about the election among the former but not the latter. First – despite a lack of evidence to this effect (e.g., Corasaniti, Epstein, & Rutenberg, 2020; Fahrenthold, Viebeck, Brown, & Helderman, 2020) – substantial majorities of Trump voters believe that voting in the U.S. is prone to fraud and is not safe/reliable (see Figure 1). Furthermore, these differences are even larger when focusing specifically on mail-in voting – a major locus of misinformation leading up to the election (Alba, 2020). For example, 77% of the Trump voters indicated believing that voting is prone to fraud (35% strongly agreed) and 78% believed mail-in voting is prone to fraud (46% strongly agreed). Only 26% of Biden voters believe voting to be prone to fraud (27% for mail-in voting).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, there was a large partisan divide in beliefs about the election outcome. When we asked participants to rate on a sliding scale from 0-100 who they believe won the election (0 = Definitely Biden, 100 = Definitely Trump; see Figure 1), a majority of Trump voters (65%) believe that it is more likely that Trump won than Biden and 30% believe it to be very likely that Trump won (95% or higher on the 100-point scale). Remarkably, a majority of Trump voters (67%) even believe it to be likely that Trump won the popular vote (which Trump is likely to have lost by more than 5 million votes). This was not likely due to confusion, as the survey instructions clearly distinguished the electoral college from the popular vote (see Methods). In contrast, virtually all Biden voters believed that Biden won both the election and the popular vote.

Would a Trump concession or legal defeats convince Trump voters to accept Biden as the President-elect?

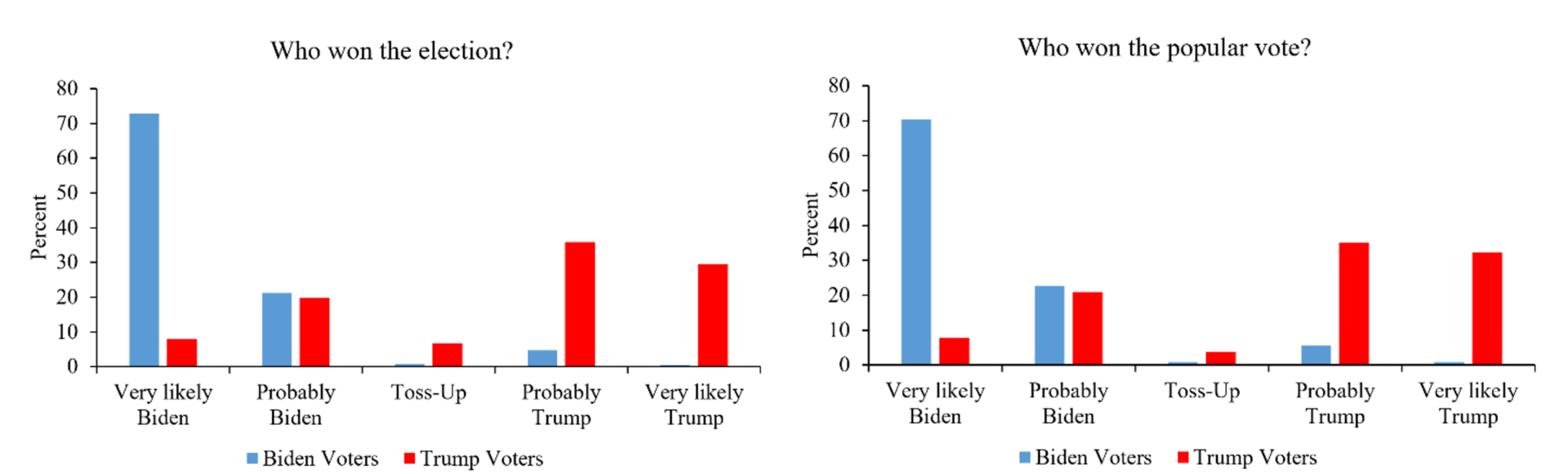

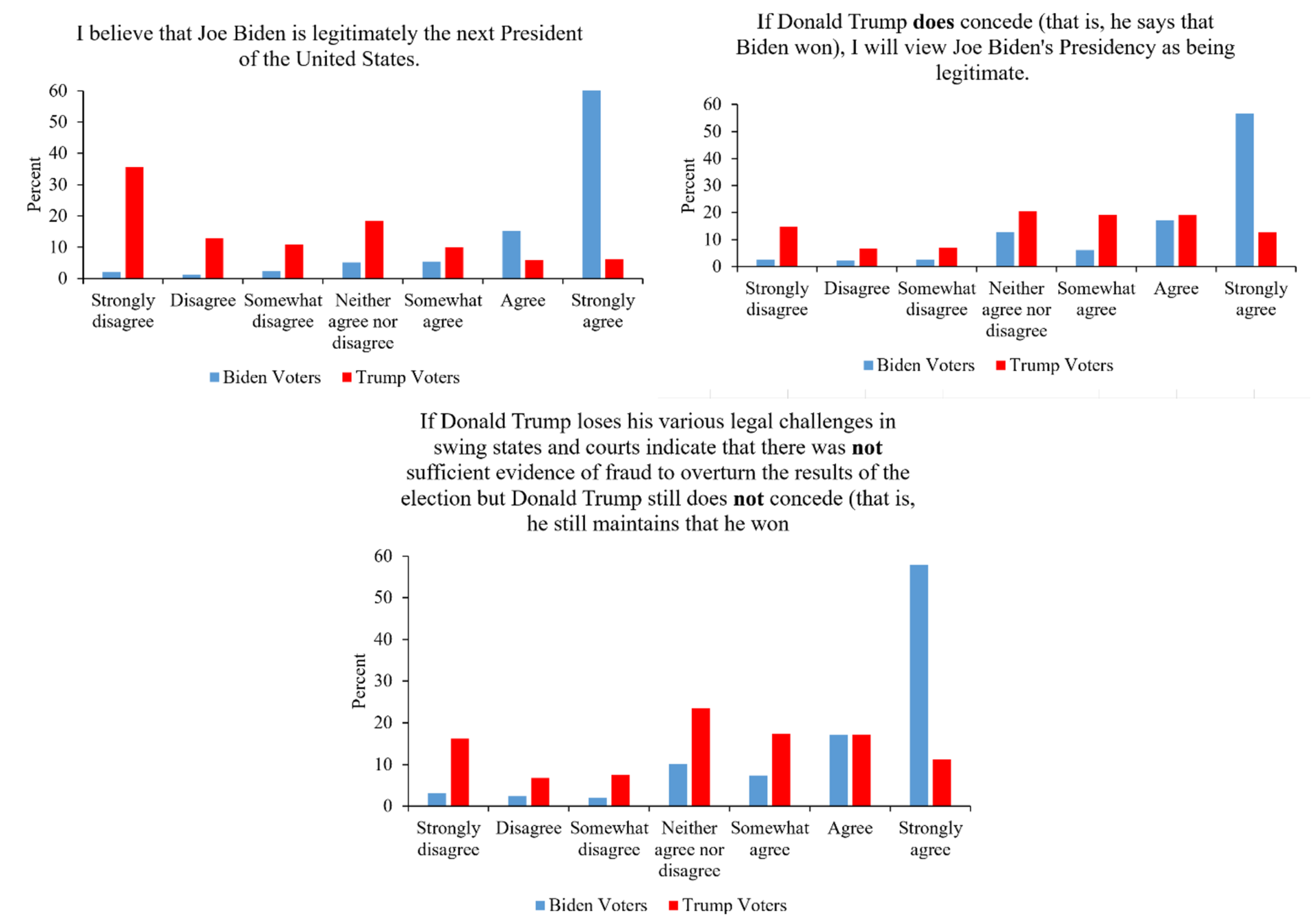

Next, we reminded participants that the major news organizations (e.g., Fox News, NBC, ABC, the Associated Press) called the election in favor of Biden, and asked if they believed that Biden was legitimately the next President. A majority of Trump voters (78%) did not agree (18.5% of which were uncertain; see Figure 3a).

Given that only 22% of Trump voters agreed that Biden was legitimately elected, understanding what would increase the perceived legitimacy of Biden’s presidency among these voters is of central importance. As shown in Figure 3b and 3c, participants indicated that they would be substantially more accepting of the legitimacy of Biden’s presidency if either Trump lost his legal challenges (but did not concede), or if Trump conceded the election. Examining the joint distribution of responses, we find that 22% of Trump voters were already convinced that Biden’s win is legitimate, 21% would be convinced either by Trump losing his legal challenges or conceding, 6% would be convinced by Trump losing his legal challenges but not by him conceding, 11% would be convinced by Trump conceding but not by him losing his legal challenges, and 40% would remain unconvinced in either case.

To summarize, most Trump voters believe him to have won the election despite the Biden having secured an electoral vote victory and there being a resounding lack of evidence for voter fraud (Corasaniti et al., 2020; Fahrenthold et al., 2020). Furthermore, 40% of Trump voters in the sample are very resistant to viewing Biden as the legitimate President even if Trump were to concede or lose his legal challenges in court.

Is widespread violence likely if Biden becomes President without Trump conceding?

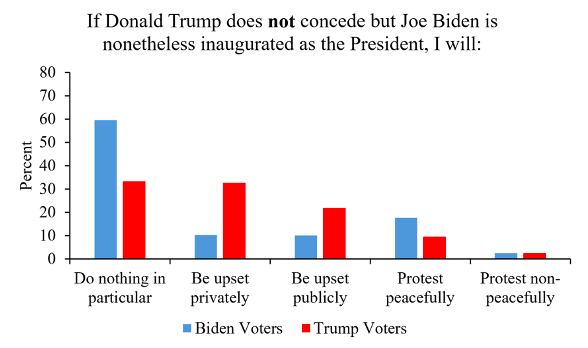

We now turn to the potential consequences of the contested election. In particular, we asked participants what they would do if Trump does not concede and Biden becomes President anyway (see Figure 4). Although most Trump voters indicated they would be upset (either privately and publicly; 66%), few indicated being willing to protest (either peacefully or non-peacefully; 12%). In fact, if anything, Biden voters indicating a stronger willingness to protest (20%), presumably because Trump failed to concede.

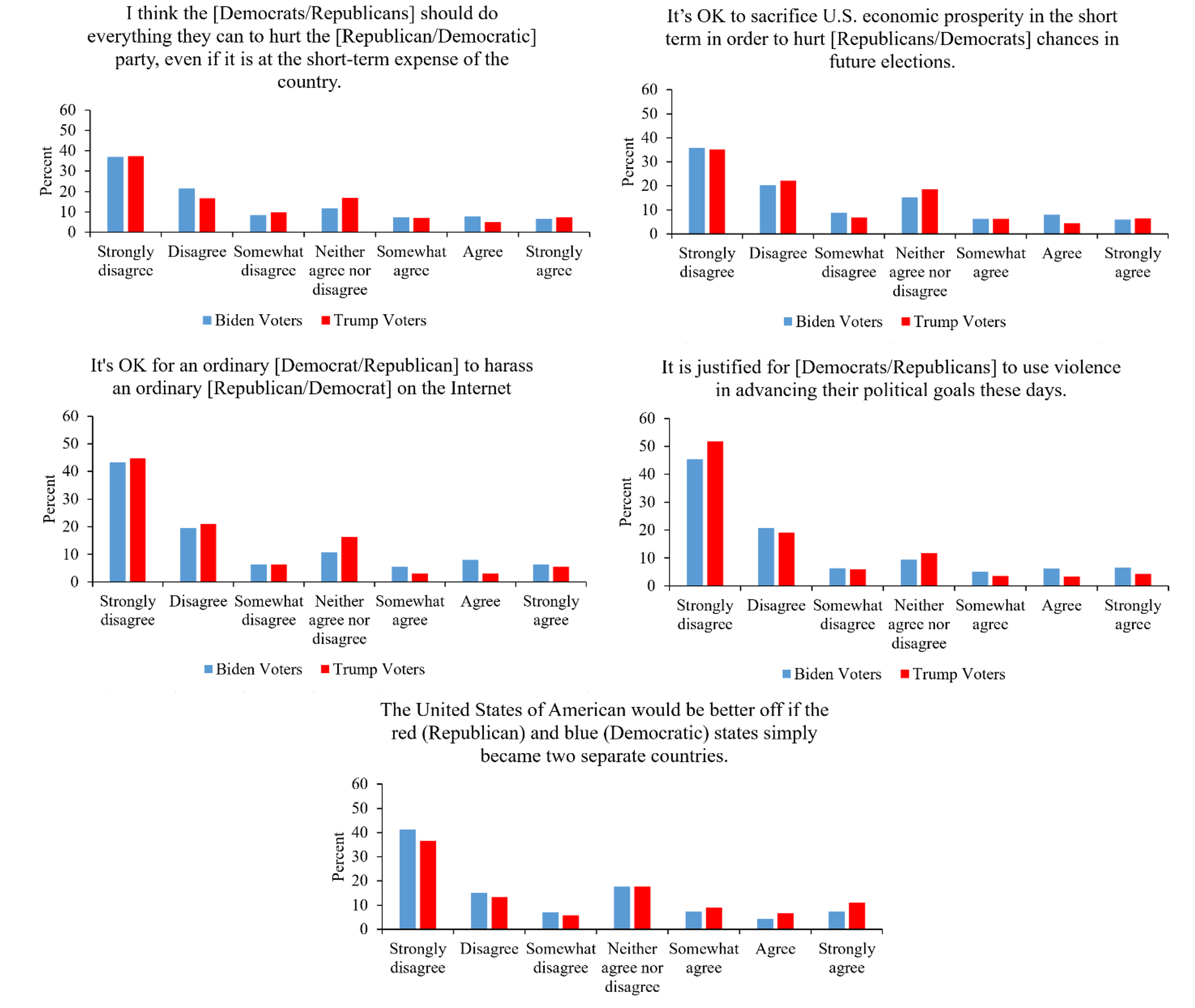

Furthermore, we also found that levels of partisan spite and endorsement of political violence were relatively low. For example, substantial majorities of both Biden and Trump voters rejected the idea of hurting the opposition party even if it comes at the expense of the country as a whole (see Figure 5, top panel). The overall level of partisan spite did not differ between Biden and Trump voters, t(1376) = .501, p = .616. Relatedly, even larger majorities rejected indications of partisan violence (see Figure 5, bottom panel). The overall level of partisan violence was actually larger for Biden voters (M = 2.58, SD = 1.82) than Trump voters (M = 2.35, SD = 1.64), t(1173.5) = 2.36, p = .019 (using a correction for unequal variances), although this should be interpreted with caution as the difference was not significant when restricting to participants who passed both attention checks (see supplement). Furthermore, majorities of both Biden (63.5%) and Trump (56%) voters also rejected the idea of dividing the United States into two separate countries of blue and red states (with most strongly disagreeing), although Trump voters favored separation more than Biden votes, t(1208.3) = 3.48, p = .001 (using a correction for unequal variances).

In summary, despite strong beliefs that Trump has won the election among Trump voters, levels of partisan spite and endorsement of political violence were equivalent to Biden voters and relatively low overall.

Attitudes towards the media, political knowledge, engagement with election news, and cognitive reflection correlate with beliefs about the election among Trump voters

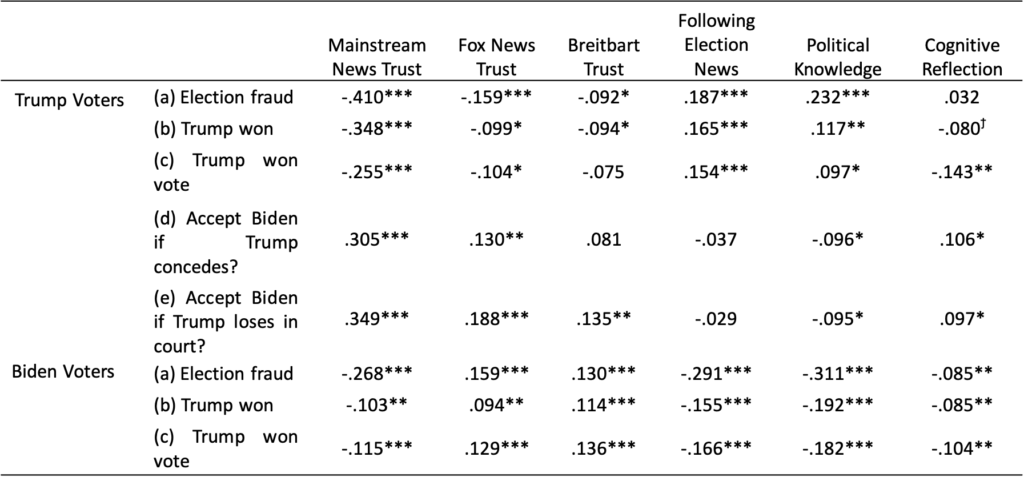

Having established that many Trump voters believe that voting is prone to fraud and that Trump won the election, we turn to the factors that might explain variation in these beliefs (Table 1). Given the strong intercorrelation between vote fraud items (r’s > .52) and across the separate vote versus mail-in vote questions (r’s > .75), we created an overall belief in voter fraud measure (see Methods). Among both Biden and Trump voters, trusting mainstream news outlets other than Fox News (CNN, MSNBC, New York Times, Washington Post, NPR, CBS, ABC, NBC; see Methods) was associated with reduced belief that fraud is common in U.S. elections and that Trump won the 2020 election. Surprisingly, trust in conservative news outlets that are both mainstream (Fox News1It is noteworthy, of course, that Fox News had called the election for Biden at this time. Breitbart had not done so, however.) and more fringe (Breitbart) was also (albeit more weakly) associated with reduced belief in election fraud and a Trump victory among Trump voters.

Higher levels of political knowledge (as measured using a fact-based test) and reported attention to election news were associated with increased belief in election fraud and a Trump victory among Trump voters. The opposite was observed among Biden voters. Thus, political knowledge and engagement were associated with increased political polarization, rather than accuracy. In contrast, cognitive reflection – a measures of one’s ability and disposition to think analytically (Frederick, 2005; Toplak et al., 2011) – was associated with a reduced belief that Trump won among Trump and Biden voters (these correlations are more robust among Trump when the analysis is restricted to individuals who passed the attention check questions; see supplement). Similar patterns also held when considering how media trust and political knowledge related to whether Trump voters would accept Biden as the President if Trump concedes or loses his various legal challenges – although following election news was not significantly correlated with these stances. Interestingly, contradicting past work relating to the 2016 election (Pennycook & Rand, 2019a), Trump and Biden voters scored similarly on the CRT (t < 1, p = .649); furthermore, Trump voters scored higher on our political knowledge test than did Biden voters, (t = 4.74, p < .001).

Methods

A full breakdown of the methods is available in the supplementary materials. Full materials and data are available on OSF: https://osf.io/8ntxm/.

We recruited a target of 2,000 participants on November 10th, 2020 via Lucid (Coppock & Mcclellan, 2019), which quota-matches to the U.S. national distribution on age, gender, ethnicity, and region. In total, 2,667 participants entered the survey. However, to retain data quality, we included an open-ended text response where participants had to correctly answer the following question to continue with the survey: “Puppy is to dog as kitten is to?”. In total, 470 participants failed this question and therefore did not contribute data. A further 179 participants did not finish the survey and were removed. The participants indicated voting in the following way: 617 voted for Trump, 1036 voted for Biden, 37 voted for a third-party candidate, 163 did not vote for reasons outside of their control, 94 who did not vote but could have, 30 who did not vote out of protest, and 41 who preferred not to say. See supplement for breakdown of demographic differences.

Participants first indicated who they voted for and answered other political affiliation/ideology questions. This was followed by questions about who they believe to have won the election and opinions about fraud, after informing them that that “news organizations (e.g., Fox News, NBC, ABC, the Associated Press) have called the election in favor of Joe Biden”, they were asked the questions about Trump conceding/losing court challenges (Figure 3 – see supplement). Next, participants completed three partisan spite (Moore-Berg et al., 2020) and four partisan violence (Kalmoe & Mason, 2019) questions in a random order. As noted in Figure 5, the questions used “Democrat” and “Republican” depending on which was the in-party and out-party for the individual (and, hence, only those who indicated an affiliation with either party were administered the questions).

Participants were asked to indicate which sources (if any) they have been following for election updates and were given the following options in a random order: CNN, ABC News, NBC News, CBS News, NPR, New York Times, Washington Post, Fox News, Breitbart, Other (with a free text box to specify). They then indicated the extent to which they trust/distrust the above sources on a scale from 1 – None at all to 5 – A great deal. They were also asked how closely they have been following the results of the election on a 4-point scale from 1 – Not following at all to 4 – Following very closely.

Finally, participants were asked a series of questions about COVID-19 (which are outside the scope of the present investigation), a 4-item Cognitive Reflection Test (word problems that cue an incorrect intuitive response and therefore permits the assessment of one’s propensity to engage in analytic thinking; Frederick, 2005; Pennycook & Rand, 2019), and a 5-item political knowledge test that included multiple-choice questions such as “Whose responsibility is it to nominate judges to Federal Courts?” These were followed by the demographic questions.

Topics

Bibliography

Alba, D. (2020, September 30). How voting by mail tops election misinformation. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/30/technology/how-voting-by-mail-tops-election-misinformation.html

Bump, P. (2020, November 11). More than 8 in 10 Trump voters think Biden’s win is not legitimate. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/11/11/more-than-8-in-10-trump-voters-think-bidens-win-is-not-legitimate/

Clayton, K., Davis, N. T., Nyhan, B., Porter, E., Ryan, T. J., & Wood, T. J. (2020). Does elite rhetoric undermine democratic norms?[Working paper]. https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/documents/democratic-norms.pdf

Corasaniti, N., Epstein, R. J., & Rutenberg, J. (2020, November 11). The Times called officials in every state: No evidence of voter fraud. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/10/us/politics/voting-fraud.html

Darcy, O. (2020, November 5). Fox News hosts sow distrust in legitimacy of election. CNN Business. https://www.cnn.com/2020/11/05/media/fox-news-prime-time-election/index.html

Edelson, J., Alduncin, A., Krewson, C., Sieja, J. A., & Uscinski, J. E. (2017). The effect of conspiratorial thinking and motivated reasoning on belief in election fraud. Political Research Quarterly, 70(4), 933–946. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917721061

Fahrenthold, D. A., Viebeck, E., Brown, E., & Helderman, R. S. (2020, November 10). Here are the GOP and Trump campaign’s allegations of election irregularities. So far, none has been proved. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-election-irregularities-claims/2020/11/08/8f704e6c-2141-11eb-ba21-f2f001f0554b_story.html

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533005775196732

Funke, D., Hendrickson, C., Jacobson, L., Kim, N. Y., & Strauss, I. (2020, November 5). Fact-checking Trump’s election fraud falsehoods in White House remarks. PolitiFact. https://www.politifact.com/article/2020/nov/06/fact-checking-falsehoods-trumps-nov-5-election-rem/

Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(4), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2182588

Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Dawson, E., & Slovic, P. (2017). Motivated numeracy and enlightened self-government. Behavioural Public Policy, 1(1), 54–86. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2016.2

Kahn, C. (2020, November 10). Nearly 80% of Americans say Biden won White House, ignoring Trump’s refusal to concede. Reuters. https://in.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-poll/nearly-80-of-americans-say-biden-won-white-house-ignoring-trumps-refusal-to-concede-reuters-ipsos-poll-idUSKBN27Q3ED

Kalmoe, N. P., & Mason, L. (2019). Lethal mass partisanship: Prevalence, correlates, and electoral Contingencies [Working paper]. https://www.dannyhayes.org/uploads/6/9/8/5/69858539/kalmoe___mason_ncapsa_2019_-_lethal_partisanship_-_final_lmedit.pdf

Kessler, G., & Rizzo, S. (2020, November 5). President Trump’s false claims of vote fraud: A chronology. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/11/05/president-trumps-false-claims-vote-fraud-chronology/

Laughlin, N., & Shelburne, P. (2020, November 9). Tracking voter trust in the American electoral system. Morning Consult. https://morningconsult.com/form/tracking-voter-trust-in-elections/

Lytvynenko, J., & Silverman, C. (2020a, November 3). Election rumors: Fact-checking the 2020 election. Buzzfeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/janelytvynenko/election-rumors-debunked?bfsource=relatedmanual

Lytvynenko, J., & Silverman, C. (2020b, November 10). Here’s A Running List Of Debunked Postelection Rumors. Buzzfeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/janelytvynenko/post-elections-debunks?bfsource=relatedmanual

Mitchell, A., Jurkowitz, M., Oliphant, J. B., & Shearer, E. (2020, September 16). Legitimacy of voting by mail politicized, leaving Americans divided. Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2020/09/16/legitimacy-of-voting-by-mail-politicized-leaving-americans-divided/

Moore-Berg, S. L., Ankori-Karlinsky, L. O., Hameiri, B., & Bruneau, E. (2020). Exaggerated meta-perceptions predict intergroup hostility between American political partisans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(26), 14864–14872. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2001263117

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2019a). Cognitive reflection and the 2016 US presidential election. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45, 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218783192

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2019b). Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition, 188, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.011

Toplak, M. E., West, R. F., & Stanovich, K. E. (2011). The Cognitive Reflection Test as a predictor of performance on heuristics-and-biases tasks. Memory & Cognition, 39(7), 1275–1289. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-011-0104-1

Wardle, C. (2018). Information disorder: The essential glossary. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/infoDisorder_glossary.pdf

Williams, P. (2020, November 23). Trump’s election fight includes over 40 lawsuits. It’s not going well. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/trump-s-election-fight-includes-over-30-lawsuits-it-s-n1248289

Zadrozny, B. (2020a, October 15). For Trump’s “rigged” election claims, an online megaphone awaits. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/trump-s-rigged-election-claims-online-megaphone-awaits-n1243309

Zadrozny, B. (2020b, November 11). Misinformation by a thousand cuts: Varied rigged election claims circulate. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/misinformation-thousand-cuts-varied-rigged-election-claims-circulate-n1247476

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Initiative of the Miami Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Reset (a project of Luminate), the John Templeton Foundation, the Canadian Institute of Health Research, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

This research was approved by the MIT Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects. Participants provided informed consent. We do not report ethnicity/gender here.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials and data needed to replicate this study are available via the Center for Open Science: https://osf.io/8ntxm/.