Peer Reviewed

Prebunking misinformation techniques in social media feeds: Results from an Instagram field study

Article Metrics

0

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Boosting psychological defences against misleading content online is an active area of research, but transition from the lab to real-world uptake remains a challenge. We developed a 19-second prebunking video about emotionally manipulative content and showed it as a Story Feed ad to N = 375,597 Instagram users in the United Kingdom. Using an innovative method leveraging Instagram’s quiz functionality (N = 806), we found that treatment group users were 21 percentage points better than controls at identifying manipulation in a news headline, with effects persisting for five months. Treated users were also more likely to click on a link to learn more. We outline how inoculation campaigns can be scaled in real-world social media feeds.

Research Questions

- Can psychological inoculation videos be implemented and scaled on a social media scroll feed?

- How can inoculation videos from the lab be optimized for ad campaigns on Instagram?

- Does a brief inoculation video boost people’s ability to correctly identify misinformation techniques in a real-world social media feed over time?

- Can a short inoculation video increase information-seeking behavior?

research note Summary

- We created and pilot-tested a very brief inoculation video that prebunks emotional manipulation online for optimization in a Story Feed Ad Campaign on Instagram.

- We applied existing ad campaign methodology to trial a novel quasi-experimental approach. Specifically, we assigned users to a treatment or control group and leveraged Instagram’s poll sticker functionality to test users’ ability to correctly identify emotional manipulation in a (fictitious) news headline after exposure to the inoculation ad, both immediately and five months later (follow-up).

- Instagram users in the treatment group were significantly and substantially better than the control group in correctly identifying emotional manipulation in a news headline. Moreover, the inoculation effect remained detectable five months later.

- Despite low base rates, Instagram users in the treatment group still clicked on a link to “learn more” about inoculation science with significantly higher frequency than the control group.

- We conclude that inoculation videos can easily be scaled and implemented on social media platforms to empower users to identify online manipulation. We encourage future research to go beyond identification and evaluate resistance to misinformation using a wider array of measures.

Implications

The spread of harmful misinformation is posing challenges to public health and democracies worldwide (Ecker et al., 2024; van der Linden et al., 2025). One of the main insights from recent research on misinformation is that addressing misinformation at the system-level is complex (Dek et al., 2025), and many experts agree that misinformation does not only include entirely false or fabricated news but importantly, also biased and misleading content (Allen et al., 2024; Altay et al., 2023; van der Linden et al., 2025). In fact, research has found that propagandistic and more subtle forms of media manipulation can have a much bigger impact on people’s attitudes than outright fact-checked misinformation (Allen et al. 2024; Ecker et al., 2024; van der Linden & Kyrychenko, 2024).

Because people often continue to rely on misinformation in their reasoning—even after having acknowledged a correction (Lewandowsky et al., 2012)—researchers have increasingly focused on more preemptive approaches to countering misinformation, including prebunking (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2024). Prebunking aims to prevent people from falling for misinformation in the first place. The most well-known method of prebunking, which we adopt here, is based on inoculation theory (McGuire, 1964; Roozenbeek et al., 2020; van der Linden, 2024) which follows the medical analogy: similar to how bodies gain resistance to infection via exposure to weakened doses of a pathogen (i.e., the vaccine), so too can individuals cultivate cognitive resistance to misinformation through preemptive exposure to a weakened dose of the techniques used to produce misinformation along with strong refutations or tips on how to spot them (Compton et al., 2021; Lewandowsky & van der Linden, 2022; Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2024; van der Linden, 2024). A vast amount of research has emerged exploring the efficacy of psychological inoculation against misinformation (for comprehensive reviews, see Compton et al., 2021; Lewandowsky & van der Linden, 2022; and Traberg et al., 2022), with meta-analyses finding that the approach significantly boosts improved discernment of misinformation (Huang et al., 2024; Simchon et al., 2025).

Most of these studies use laboratory experiments, detached from how people might (or might not) interact with prebunking interventions on social media (Roozenbeek et al., 2024). One exception is Roozenbeek et al. (2022), who conducted a randomized field study on YouTube where, as part of a large advertising campaign targeting consumers of U.S. political news, short prebunking videos were placed in the ad spaces (before potential exposure to harmful content). Individuals were prompted with a quiz within 24 hours to see if they could accurately spot the manipulation technique they were inoculated against, leading to an average boost of about 5% to 10% in correct technique recognition in the treated group compared to controls (Roozenbeek et al., 2022). Google has since validated and rolled out these, as well as other prebunking videos, to hundreds of millions of people (Jigsaw, 2023).

However, it remains unclear how and to what extent this approach extends to social media platforms where users interact with media content in a different way. In their experiment, Roozenbeek et al. (2022) leveraged a commercial ad campaign and the so-called “brand lift” (polling) function to evaluate their campaign on YouTube, but little is known about how this methodology could be extended to other social media platforms where users might quickly scroll through headlines with limited attention. Some experiments have attempted to look at the potential for inoculation by using a simulated social media feed with mixed success (cf. McPhedran et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2025). The major downside is that those experiments, while internally valid, are not representative of what people might do on a real social media feed when targeted with ads (as is common during political campaigns). Accordingly, we launched an inoculation campaign on a live Instagram scroll feed to evaluate the potential for psychological inoculation against online manipulation in the real-world.

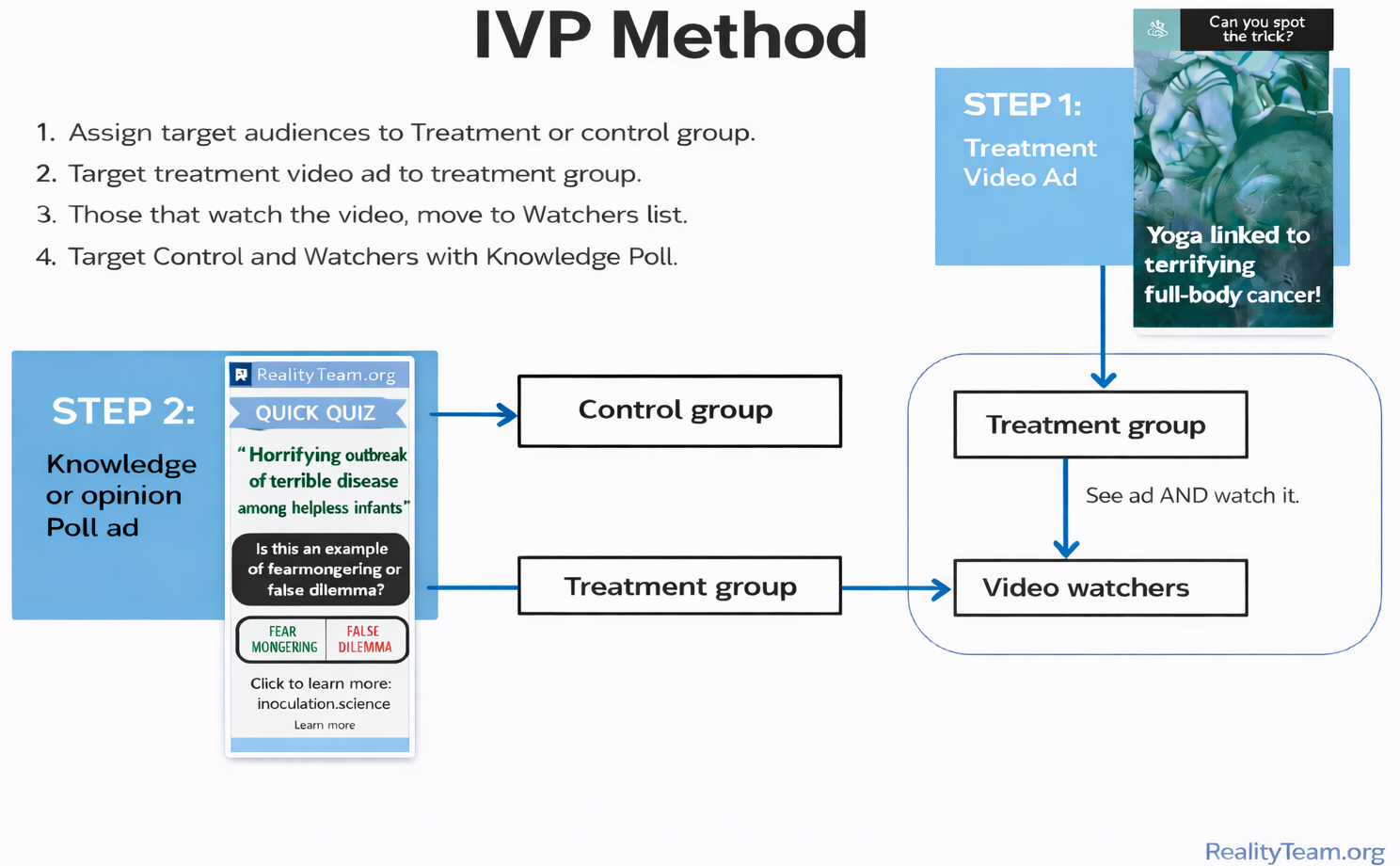

Specifically, we designed and tested a short prebunking video that inoculates people against emotionally manipulative content on social media (see Appendix A). Misinformation is known to exploit emotions on social media by eliciting outrage and other negative emotions (McLoughlin et al., 2024). Although emotions are valuable to communication, they can be used deceptively by steering people away from facts and evidence, a tactic known as the appeal-to-emotion fallacy (Hamlin, 1970; Walton, 1987). Indeed, people are more likely to accept misinformation in an emotional state (Martel et al., 2020) and much research has shown that misinformation contains significantly more negative emotions than non-manipulative content (Carrasco-Farré, 2022; Fong et al., 2022; Kauk et al., 2025; Mcloughlin et al., 2024; Vosoughi et al., 2018). Prior research has found that inoculating people against the appeal-to-emotion fallacy improves discernment between manipulative and non-manipulative information (Traberg et al., 2024). Accordingly, we designed an Instagram campaign that targeted 375,597 users between the ages of 18 and 34 in the United Kingdom with a 19-second prebunking video ad in the Story Feed on Instagram. The ad forewarned users of emotional manipulation on social media using a weakened dose example of fearmongering with a fake headline that claimed “Yoga linked to terrifying full body cancer” (see Figure 1 and Appendix A).

Our results have important implications for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners:

- We provide real-world evidence that brief prebunking videos can be scaled inexpensively and deployed as ads to many thousands of social media users in the context of a scroll feed where attention to accuracy may be limited (Searles & Feezell, 2023). We also note that relatively minor changes to color, length, and tone of the videos can impact engagement metrics (see Appendix A). Future efforts could achieve higher view rates with additional A/B pretests of message variants. We also note the importance of exploring cultural variation in engagement and effectiveness of inoculation campaigns on global platforms such as Instagram, as the type, meaning, and prevalence of misinformation techniques might differ across platforms and cultures (BBC, 2025). This variation is important in light of ongoing discussions about how to optimize the uptake of interventions (Roozenbeek, Young, & Madsen 2024; Roozenbeek et al., 2025).

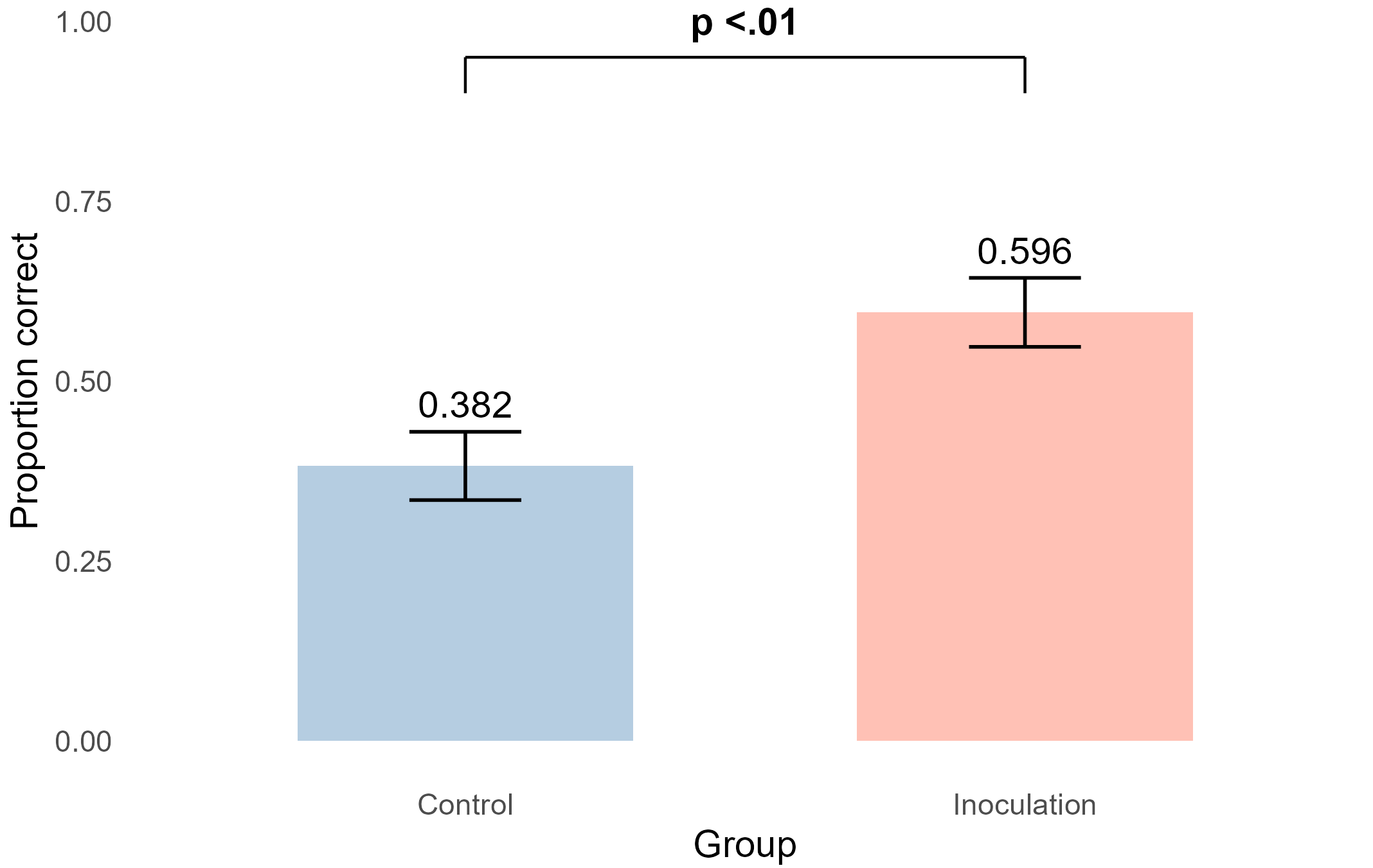

- We found that baseline recognition of emotional manipulation is poor (38%) among polled Instagram users (note 50% equals chance). Encouragingly, the campaign substantially boosted Instagram users’ ability to spot fearmongering online by about 21 ppts (compared to controls). This is important because we selected the age range (18-34) based on recent research which finds that younger audiences are more susceptible to misinformation (Kyrychenko et al., 2025).

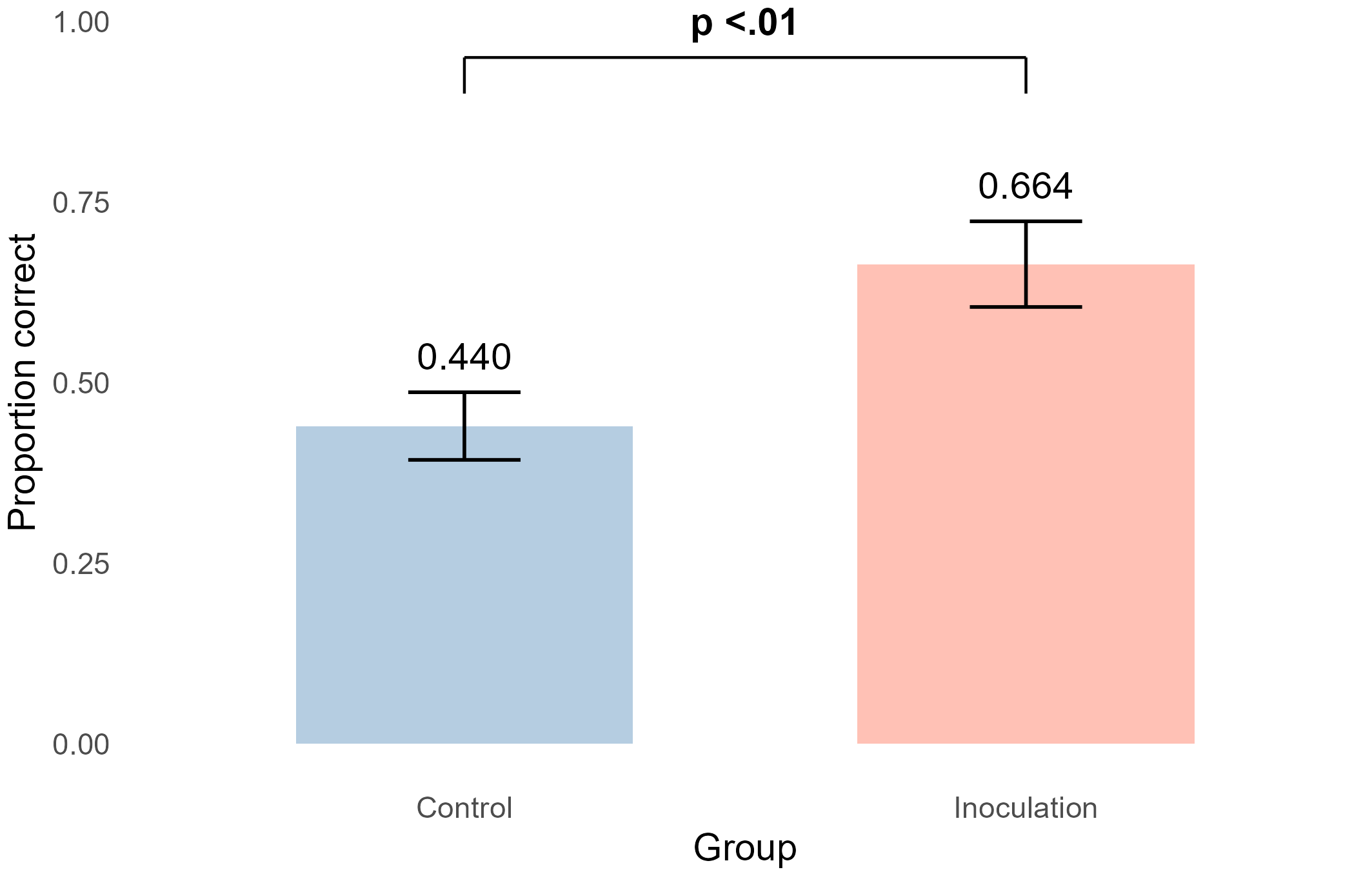

- We also show that the treatment effect remained stable (at the group-level) for 5 months, which is notable given that inoculation effects often wear off over time (Maertens et al., 2025).

- These findings are particularly important in light of the fact that negative and outgroup-hostile content is often shared more to social media (Marks et al., 2025; Watson et al., 2024) and informal fallacies, such as appeals-to-emotion, are frequently deployed by populist politicians during election campaigns (Blassnig et al., 2019). Accordingly, it is promising that a short video can help audiences identify emotional manipulation.

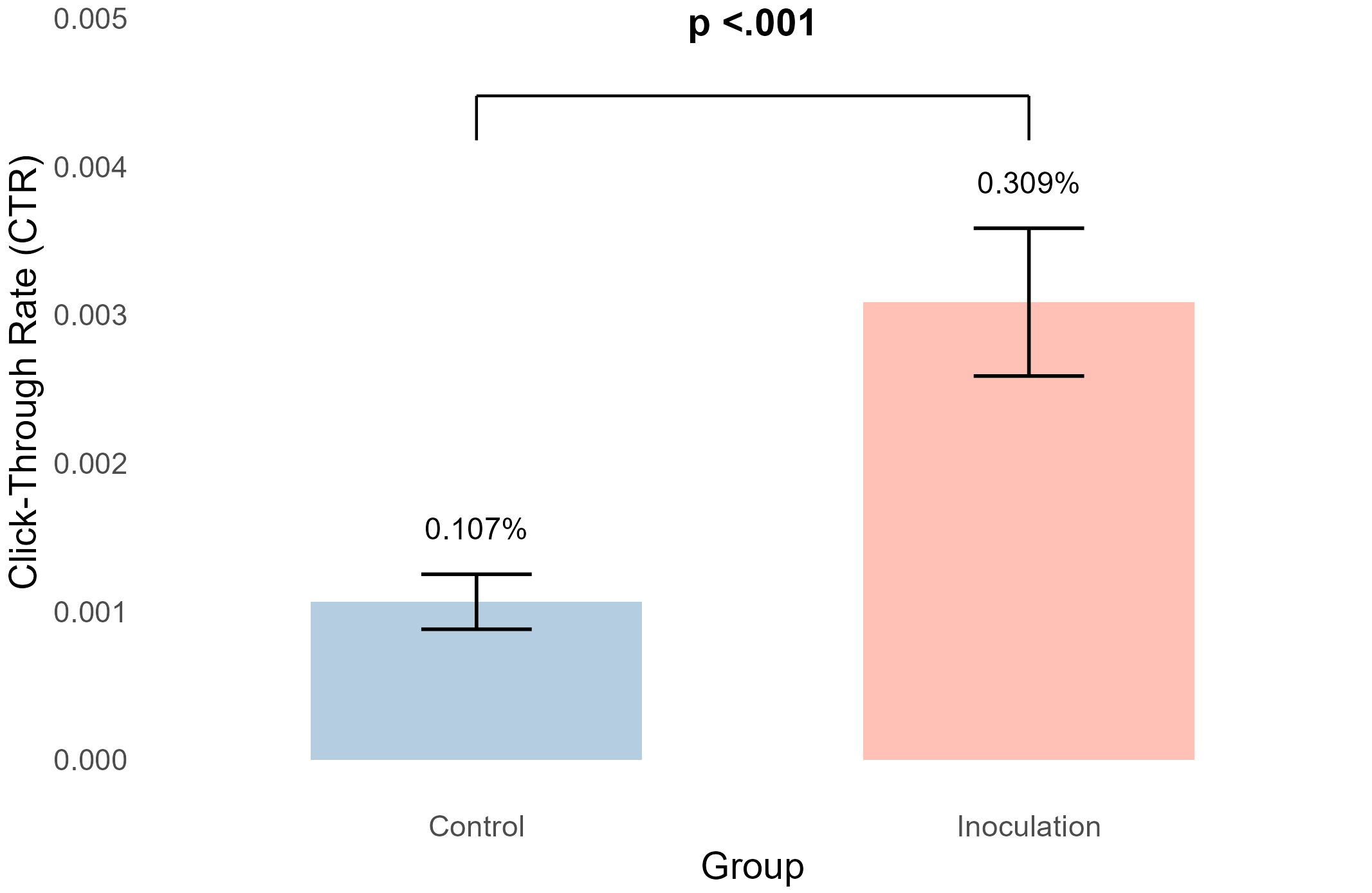

- We also found significant differences in information-seeking behavior insofar the click-through rate (CTR) on the ad to learn more about prebunking was about three times higher in the treatment group compared to the control group, which suggests that inoculation interventions can alter (digital) behavior. Future research could pair CTRs with browser data via pixels to record web activity to see what additional information-seeking behavior users engage in on the website.

Limitations of our approach include the fact that although there is strong correspondence between technique identification and cognitive resistance (e.g., lower reliability ratings of misleading posts) in lab studies (Roozenbeek et al., 2022), identification is just one (first) step in the resistance process, and we do not have data on mechanisms (e.g., counter-arguing, motivation to resist) or people’s credibility ratings here, given that the poll only allows for a single-item. However, instead of technique recognition, future research could ask whether people also find specific content (un)reliable, model (sharing) discernment using inferential methods, and assess potential network effects (e.g., to examine if people share the inoculation video with others in their social network). We also note that the response rate to the poll is relatively low (~1%), that pure randomization to groups is not possible within the Instagram ad manager (see methods for our approximation), and that it is not possible to know whether the follow-up sample contains responses from the same users who filled out the initial poll (though we deem this unlikely given the large sample).

Further, Instagram only allows for a single test item with just two options, which limits measurement validity, and we only tested a single technique, so future research should investigate the generalizability of inoculation campaigns to other issues and platforms (though prior research on YouTube with multiple choice items has been promising in this regard; see Roozenbeek et al., 2022; Jigsaw, 2023). Users also self-selected both in terms of watching the treatment video and responding to the poll, which may have introduced a response bias insofar as more motivated users are more likely to watch the video (though opt-in bias for at least the poll is symmetrical between the control and treatment groups). Meta’s algorithm also introduces potential unknown biases as they optimize ad delivery to those most likely to respond to the ad but that is true of any real-world social media campaign (which is the focus of our study).1Meta’s algorithm uses machine learning to estimate a person’s “action rate” (i.e., the likelihood someone takes the desired action of the ad, such as views or clicks). The algorithm takes into account both on-platform (e.g., relevant prior likes and posts) and off-platform (e.g., website visits, app purchases) features as well as the content of the ad, explicit user feedback, and the time of day, to optimize ad delivery to their users (Meta, 2020).

Findings

Finding 1: Short prebunking ads increase correct recognition of emotional manipulation on social media.

Users were invited to complete a poll sticker in their story feed (see Figure 1), which tested their ability to evaluate the correct manipulation technique in a single headline. We targeted 188,137 users in the control group and 45,285 users in the treatment group in order to receive n = 403 poll responses in each group (total n = 806, see methods for sample and targeting details). The time-lapse between ad exposure and poll completion ranged from 24 hours to 10 days.

On average, 59.55% of users correctly identified emotional manipulation in the treatment group (40.45% incorrect) compared to only 38.21% in the control group (61.79% incorrect). A two-proportion z-test was statistically significant with a medium effect-size X2(1) = 35.87, p < .001, h = 0.43. Correct discernment or the “lift” on the ad (the difference between % correct in the treatment versus control group) is 21.4 percentage points (95%CI [14.6, 28.0]; see Figure 2 and Appendix B).

Finding 2: Correct recognition of emotional manipulation remains stable over five months.

We polled the treatment and control groups again, though we did not achieve the same sample sizes due to differential attrition at follow-up (Ncontrol = 432, Ntreatment = 244), and we do not know whether the follow-up contains responses from the same individuals as the initial poll. However, we deem this unlikely given the large pool from which we sampled (total reach in the control group was N = 160,416 and N = 39,354 in the treatment group). We therefore evaluated this as a repeated cross-sectional test five months later. On average, 66.39% of users still correctly identified emotional manipulation in the quiz in the treatment group (33.61% incorrect) compared to only 43.98% in the control group (56.02% incorrect). A two-proportion z-test was statistically significant with a medium effect-size X2(1) = 31.38, p < .001, h = 0.45. The “lift” on the ad remained stable at 22.21 percentage points (95%CI [14.85, 29.96]; see Figure 3).

Finding 3: Short prebunking ads significantly increase information-seeking behavior.

As an exploratory measure of information-seeking behavior, Instagram users could click on a link below the poll quiz (Figure 1) to learn more about the science of inoculation against misinformation. The click-through rate (CTR) is calculated as the number of clicks divided by the total impressions. In total, 147 link clicks were recorded in the treatment group (out of 47,623 ad impressions), which was significantly higher than the control group (127 clicks) out of 119,101 ad impressions, X2(1) = 84.61, p < .001, h = 0.05 (Figure 4 and Appendix B). Although small in absolute terms, the CTR was approximately 3 times higher in the treatment group (0.31%) compared to the control group (0.11%). This difference of 0.20 percentage points, 95% CI (0.148, 0.255), can be considered meaningful given the low base rate of this behavior on social media (CTRs are often < 1%; see Grigaliūnaitė, 2025). Five months later, 108 link clicks were recorded in the treatment group (out of 39,354 ad impressions, or 0.274%), which remained significantly higher than the control group (166 clicks out of 163,555 impressions or 0.101%, X2(1) = 70.35, p < .001, h = 0.04).

Methods

Instagram campaign method and sample

We partnered with Google Jigsaw and Reality Team—a U.S.-based NGO with experience in evaluating media literacy campaigns on social media. Jointly, we designed a treatment video2https://shorturl.at/mX4cO to appear in the Story Feed of Instagram users. The video was just under 20 seconds long and was designed to be simple to attract the attention of those who may not otherwise have an interest in spotting disinformation. The video ad aimed to inoculate users by forewarning them of emotional manipulation on social media (Roozenbeek et al., 2022) using a weakened-dose example of fearmongering with a fake headline that claimed, “Yoga linked to terrifying full body cancer” (see Figure 1).

We designed an Instagram campaign that targeted 375,597 users between the ages of 18 and 34 in the United Kingdom with the aforementioned prebunking video ad, which appeared in the Story Feed on Instagram. A key criterion of the campaign was that users needed to watch at least 50% of the video in order to move to the “watch-list” to be eligible for our subsequent poll. We did not deem it informative to test users who did not watch the video, so we set 50% playtime as the minimum requirement. There is debate about the benefits and drawbacks of intention-to-treat (i.e., all users) and “as-treated” or “per-protocol” designs (Molero-Calafell et al., 2024; Roozenbeek et al., 2025), with our study being conceptually closer to the latter (i.e., high compliance) rather than the former. While per-protocol designs often represent “best case” scenarios, ITT designs have a stronger causal design but can greatly dilute power to detect treatment effects (Roozenbeek et al., 2025). We first ran some small pilot studies to optimize the ad for the audience (e.g., color, tone, music) and ensure sufficient engagement with the poll (see Appendix A). Based on a power calculation (alpha = 0.05, power = 0.90) for a two-proportion Z-test using effect-sizes from Roozenbeek et al. (2022), we aimed for roughly 400 poll responses per group (n = 800 total). Based on Reality Team’s prior experience, we expected 10% to 20% of users to convert to the watchlist and 1%-2% of the watchlist to respond to the poll. Accordingly, we set the range for the watchlist audience between 40,000 and 55,000. The video ad campaign ran for six days from February 5 to 11, 2025 (after which the polls started). In total, we reached 375,597 unique Instagram users, with the campaign accruing 889,336 impressions (i.e., the number of times the ad was shown on screen). The treatment-to-watchlist conversation rate was 12.05% with 45,285 users on the watchlist. The campaign garnered 472,612 video views and 49,100 recorded plays (10.38%) watched the video at least halfway through (people can view the video multiple times). We then polled users from the watchlist (n = 45,285) to see if the treatment group (n = 403, 0.85% response rate) became better at identifying manipulative information than the control group, which was comprised of 119,101 users (n = 403 responses, 0.34% response rate). For the follow-up study in July of 2025 (five months later), response rates dropped, but we were able to collect n = 432 responses in the control group (reach = 160,416) and n = 244 in the treatment group (reach = 39,354).

Poll and randomization procedure

The control group was comprised of 18–34-year-olds in the United Kingdom who, by design, did not watch the video (and were drawn from a much larger group, so the response rate could be lower whilst still obtaining a similar sample size). Lab experiments allow for random assignment to experimental conditions, but this is more difficult in field experiments. True randomized assignment to a treatment or control group is impossible within the Instagram ad manager. We therefore created a quasi-experimental procedure by assigning participants to a treatment or control condition based on self-declared birth months (users with birth months April, July, and October were assigned to the control group). Birth month is a profile element that can be targeted in the Instagram ad manager, and it is our best approximation of random assignment: we expect any predictable variation in baseline ability to identify misinformation between Instagram users born in (for example) April and June to be negligible. We note that not all Meta users declare their birth month, which introduces a potential sampling bias. Once we had a sufficiently large list of people who watched the treatment video at least 50% of the way through (based on our targets), we polled both the treatment and control groups.

The poll itself was a standard Story Feed ad that included a Poll Sticker feature. The video ad and poll were both presented in the Story Feed to ensure consistency in the user base. The Poll Sticker only allows for a single, binary question. The format, look, and feel of the question is fixed (see Figure 1), but we placed the correct answer to the left to ensure intentional swiping. The campaign ran for six days during February 2025, after which users from either the treatment or control group were invited to complete a poll sticker in the story feed (see Figure 1), which tested users’ ability by having them evaluate the correct manipulation technique using a binary question. The time-lapse between ad exposure and poll completion ranged from 24 hours to 10 days—a larger delay than in Roozenbeek et al. (2022). In total, 806 users completed the poll in both the treatment and control groups during the main campaign period.

Topics

Bibliography

Allen, J., Watts, D. J., & Rand, D. G. (2024). Quantifying the impact of misinformation and vaccine-skeptical content on Facebook. Science, 384(6699), Article eadk3451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adk3451

Altay, S., Berriche, M., Heuer, H., Farkas, J., & Rathje, S. (2023). A survey of expert views on misinformation: Definitions, determinants, solutions, and future of the field. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 4(4), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-119

American Academy of Pediatrics (2025, October 29). Acetaminophen is safe for children when taken as directed, no link to autism. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/fact-checked/acetaminophen-is-safe-for-children-when-taken-as-directed-no-link-to-autism/

BBC (2025, August 28). What if we could vaccinate against mis-and disinformation? https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/insight-and-impact/insightblog/vaccinate-against-disinformation

Blassnig, S., Büchel, F., Ernst, N., & Engesser, S. (2019). Populism and informal fallacies: An analysis of right-wing populist rhetoric in election campaigns. Argumentation, 33(1), 107–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-018-9461-2

Bïrch (2025). Instagram advertising costs by CPM. https://app.bir.ch/instagram-advertising-costs

Bellingcat (November 4, 2024). What Meta’s ad library shows about Harris and Trump’s campaigns on Facebook and Instagram. https://www.bellingcat.com/resources/2024/11/04/us-presidential-election-trump-harris-meta-ads/

Dek, A., Kyrychenko, Y., van der Linden, S., & Roozenbeek, J. (2025). Mapping the online manipulation economy. Science, 390(6778), 1112–1114. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adw8154

Ecker, U., Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., Tay, L. Q., Cook, J., Oreskes, N., & Lewandowsky, S. (2024). Misinformation poses a bigger threat to democracy than you might think. Nature, 630(8015), 29–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01587-3

Carrasco-Farré, C. (2022). The fingerprints of misinformation: How deceptive content differs from reliable sources in terms of cognitive effort and appeal to emotions. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01174-9

Compton, J., van der Linden, S., Cook, J., & Basol, M. (2021). Inoculation theory in the post‐truth era: Extant findings and new frontiers for contested science, misinformation, and conspiracy theories. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(6), Article e12602. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12602

Fong, A., Roozenbeek, J., Goldwert, D., Rathje, S., & van der Linden, S. (2021). The language of conspiracy: A psychological analysis of speech used by conspiracy theorists and their followers on Twitter. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(4), 606–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302209875

Grigaliūnaitė, J. (2025, July 25). What is a good CTR for ads? 2025 benchmarks across TikTok, Meta & YouTube. Billo. https://billo.app/blog/what-is-a-good-ctr/

Hamlin, C. L. (1970). Fallacies. Methuen & Co.

Huang, G., Jia, W., & Yu, W. (2024). Media literacy interventions improve resilience to misinformation: A meta-analytic investigation of overall effect and moderating factors. Communication Research, Article 00936502241288103. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502241288103

Jigsaw (2023, October 25). Prebunking to build defenses against online manipulation tactics in Germany. Medium. https://medium.com/jigsaw/prebunking-to-build-defenses-against-online-manipulation-tactics-in-germany-a1dbfbc67a1a

Kauk, J., Humprecht, E., Kreysa, H., & Schweinberger, S. R. (2025). Large-scale analysis of online social data on the long-term sentiment and content dynamics of online (mis) information. Computers in Human Behavior, 165, Article 108546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108546

Kyrychenko, Y., Koo, H. J., Maertens, R., Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., & Götz, F. M. (2025). Profiling misinformation susceptibility. Personality and Individual Differences, 241, Article 113177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2025.113177

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

Lewandowsky, S., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Countering misinformation and fake news through inoculation and prebunking. European Review of Social Psychology, 32(2), 348–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2021.1876983

Lu, C., Hu, B., Li, Q., Bi, C., & Ju, X. D. (2023). Psychological inoculation for credibility assessment, sharing intention, and discernment of misinformation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, Article e49255. https://doi.org/10.2196/49255

Maertens, R., Roozenbeek, J., Simons, J. S., Lewandowsky, S., Maturo, V., Goldberg, B., Xu, R., & van der Linden, S. (2025). Psychological booster shots targeting memory increase long-term resistance against misinformation. Nature Communications, 16(1), Article 2062. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57205-x

Marks, M., Kyrychenko, Y., Gärdebo, J., & Roozenbeek, J. (2025). Ingroup solidarity drives social media engagement after political crises. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(35), Article e2512765122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2512765122

Martel, C., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Reliance on emotion promotes belief in fake news. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 5(1), Article 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-020-00252-3

Metalla, F. (2025, January 13). Meta ad hooks that drive conversions in 2025: The ultimate guide for Facebook & Instagram ads. Metalla Digital. https://metalla.digital/meta-ad-hooks-that-drive-conversions-in-2025/

McGuire, W. J. (1964). Some contemporary approaches. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 191–229). Academic Press.

McPhedran, R., Ratajczak, M., Mawby, M., King, E., Yang, Y., & Gold, N. (2023). Psychological inoculation protects against the social media infodemic. Scientific Reports, 13(1), Article 5780. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32962-1

McLoughlin, K. L., Brady, W. J., Goolsbee, A., Kaiser, B., Klonick, K., & Crockett, M. J. (2024). Misinformation exploits outrage to spread online. Science, 386(6725), 991–996. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adl2829

Molero-Calafell, J., Burón, A., Castells, X., & Porta, M. (2024). Intention to treat and per protocol analyses: Differences and similarities. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 173, Article 111457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2024.111457

Pennycook, G., Berinsky, A. J., Bhargava, P., Lin, H., Cole, R., Goldberg, B., Lewandowsky, S., & Rand, D. G. (2024). Inoculation and accuracy prompting increase accuracy discernment in combination but not alone. Nature Human Behaviour, 8(12), 2330–2341. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-02023-2

Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., & Nygren, T. (2020). Prebunking interventions based on “inoculation” theory can reduce susceptibility to misinformation across cultures. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-008

Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., Goldberg, B., Rathje, S., & Lewandowsky, S. (2022). Psychological inoculation improves resilience against misinformation on social media. Science Advances, 8(34), Article eabo6254. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo6254

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2024). The psychology of misinformation. Cambridge University Press.

Roozenbeek, J., Remshard, M., & Kyrychenko, Y. (2024). Beyond the headlines: On the efficacy and effectiveness of misinformation interventions. Advances in Psychology, 2, Article e24569. https://doi.org/10.56296/aip00019

Roozenbeek, J., Young, D., & Madsen, J. K. (2025). The wilful rejection of psychological and behavioural interventions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 66, Article 102138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2025.102138

Roozenbeek, J., Lasser, J., Marks, M., Qin, T., Garcia, D., Goldberg, B., Debnath, R., van der Linden, S., & Lewandowsky, S. (2025). Misinformation interventions and online sharing behavior: Lessons learned from two preregistered field studies. Royal Society Open Science, 12(11), Article 251377. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.251377

Searles, K., & Feezell, J. T. (2023). Scrollability: A new digital news affordance. Political Communication, 40(5), 670–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2023.2208083

Simchon, A., Zipori, T., Teitelbaum, L., Lewandowsky, S., & van der Linden, S. (2025). A signal detection theory meta-analysis of psychological inoculation against misinformation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 67, Article 102194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2025.102194

Stuart, D. (2025). “I have no future”-the critical need to counter climate doomism. Environmental Sociology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2025.2552388

Traberg, C., Morton, T., & van der Linden, S. (2024). Counteracting socially endorsed misinformation through an emotion-fallacy inoculation. Advances in Psychology, 2, Article e765332. https://doi.org/10.56296/aip00017

Traberg, C. S., Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2022). Psychological inoculation against misinformation: Current evidence and future directions. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 700(1), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162221087936

Traberg, C., Morton, T., & van der Linden, S. (2024). Counteracting socially endorsed misinformation through an emotion-fallacy inoculation. Advances in Psychology, 2, Article e765332. https://doi.org/10.56296/aip00017

van der Linden, S., Albarracín, D., Fazio, L., Freelon, D., Roozenbeek, J., Swire-Thompson, B., & Van Bavel, J. (2025). Using psychological science to understand and fight health misinformation: An APA consensus statement. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001598

van der Linden, S., & Kyrychenko, Y. (2024). A broader view of misinformation reveals potential for intervention. Science, 384(6699), 959–960. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adp9117

van der Linden, S. (2023). Foolproof: Why misinformation infects our minds and how to build immunity. WW Norton & Company.

van der Linden, S. (2024). Countering misinformation through psychological inoculation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 69, 1–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2023.11.001

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Walton, D. N. (1987). Informal fallacies. John Benjamins Publishing.

Watson, J., van der Linden, S., Watson, M., & Stillwell, D. (2024). Negative online news articles are shared more to social media. Scientific Reports, 14(1), Article 21592. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71263-z

Funding

The study and associated social media campaign reported in this paper were funded by Google (Jigsaw).

Competing Interests

Lavoy, N. Blazer, and N. Noble are employed by Reality Team. S. van der Linden and J. Roozenbeek received research funding from Google Jigsaw.

Ethics

The research study received a favorable opinion from the Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee (PRE. 2024.093). Human subjects could not provide informed consent because the poll was carried out on Instagram as a field study using the quiz functionality, which has no capability to ask for or record consent. This was declared in the application and reviewed by the committee. The research team had prior approval from Meta to run social issue campaigns. Gender was not of concern to the campaign, but is reported in the dataset; categories (male/female/unknown) are determined solely by Instagram.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YHXOUK

Acknowledgements

We thank Reality Team and Beth Goldberg, Meghan Graham, and Erick Fletes at Google Jigsaw for their help in planning and designing the stimuli and social media campaign.