Peer Reviewed

People are more susceptible to misinformation with realistic AI-synthesized images that provide strong evidence to headlines

Article Metrics

0

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

The development of artificial intelligence (AI) allows rapid creation of AI-synthesized images. In a pre-registered experiment, we examine how properties of AI-synthesized images influence belief in misinformation and memory for corrections. Realistic and probative (i.e., providing strong evidence) images predicted greater belief in false headlines. Additionally, we found preliminary evidence that paying attention to properties of images could selectively lower belief in false headlines. Our findings suggest that advances in photorealistic image generation will likely lead to greater susceptibility to misinformation, and that future interventions should consider shifting attention to images.

Research Questions

- Do the properties (realism, evidence strength, and surprisingness) of AI-synthesized images predict belief in false headlines?

- How do properties of AI-synthesized images influence correction effectiveness?

- How does examining realism, evidence strength, and surprisingness of images influence subsequent belief in headlines?

- How are digital literacy, conspiracist tendencies, and analytical thinking associated with headline discernment?

Research note summary

- This pre-registered study examined whether participants’ subjective ratings of image realism, image surprisingness, and evidence strength predicted their belief in false headlines and the effectiveness of corrections to those headlines. We compared belief in headlines across two experiments to examine the effect of completing image ratings prior to belief ratings.

- False headlines that were paired with realistic images and images that provided strong evidence were believed to a greater extent, and preliminary evidence showed that rating properties of images may decrease belief in false headlines. Corrections were generally memorable and effective at reducing belief.

- Our findings highlight that advances in generative AI image models could lead to increased misinformation susceptibility. Carefully examining the properties of images could be an effective intervention to reduce belief in misinformation, but further research is needed.

Implications

In past years, “photographs” of politicians being arrested, the pope in high fashion, and world landmarks ablaze circulated the internet. Many of these images were subsequently debunked as AI-generated and thus entirely fictional. Proliferation of AI-generated visual misinformation may exacerbate existing public health issues (Heley et al., 2022), reduce trust in media (Karnouskos, 2020; Ternovski et al., 2022), and influence voter attitudes (Diakopoulos & Johnson, 2021; Dobber et al., 2021). Despite this threat, how different properties of images are associated with initial belief in AI-generated visual misinformation and the effectiveness of corrections remains uncertain.

Findings from our experiment showed that the realism of images and the amount of evidence they provided to headlines were significant positive predictors of belief in false headlines. Therefore, we suggest that social media platforms should develop algorithms that can categorize these dimensions of images (i.e., realism and evidence strength) and detect whether these images may be AI-synthesized. When users upload images to social media, the algorithms could then identify highly realistic images that provide strong evidence to the accompanying text as greater potential misinformation risks, prioritizing content reviews of those posts. Fact-checking organizations could benefit from adopting similar algorithms. While fact-checking has proven effective in reducing the intent to share misinformation (Yaqub et al., 2020), the sheer volume of AI-generated images circulating online makes it challenging to address each one individually. Therefore, an automated system that identifies and prioritizes the most persuasive or potentially harmful misinformation could help fact checkers focus their efforts.

Following correction, belief in the misinformation was not significantly associated with perceived realism or evidence strength, indicating that corrective interventions are similarly effective across different image types. This finding further reinforces the idea that social media platforms or fact checkers should develop algorithms that automatically detect persuasive misinformation. If corrective measures yield comparable outcomes for both persuasive and non‑persuasive misinformation, it may be more efficient to prioritize resources toward identifying and correcting persuasive misinformation.

Participants who scrutinized images and headlines to rate realism, evidence strength, and surprisingness prior to assessing headline believability exhibited selectively lower belief in misinformation headlines. This preliminary finding suggests that interventions that direct focus to images when evaluating the credibility of headlines could reduce belief in false headlines that are paired with convincing AI-synthesized images. Therefore, social media platforms and government organizations should consider updating existing media literacy guidelines with greater emphasis on paying attention to AI-synthesized images (Guo et al., 2025). However, given the small effect size, further research is warranted to clarify the role of image-focused attention in mitigating misinformation beliefs. For example, researchers could test accuracy nudges that prompt users to carefully examine images compared to those that only encourage checking the accuracy of a textual claim.

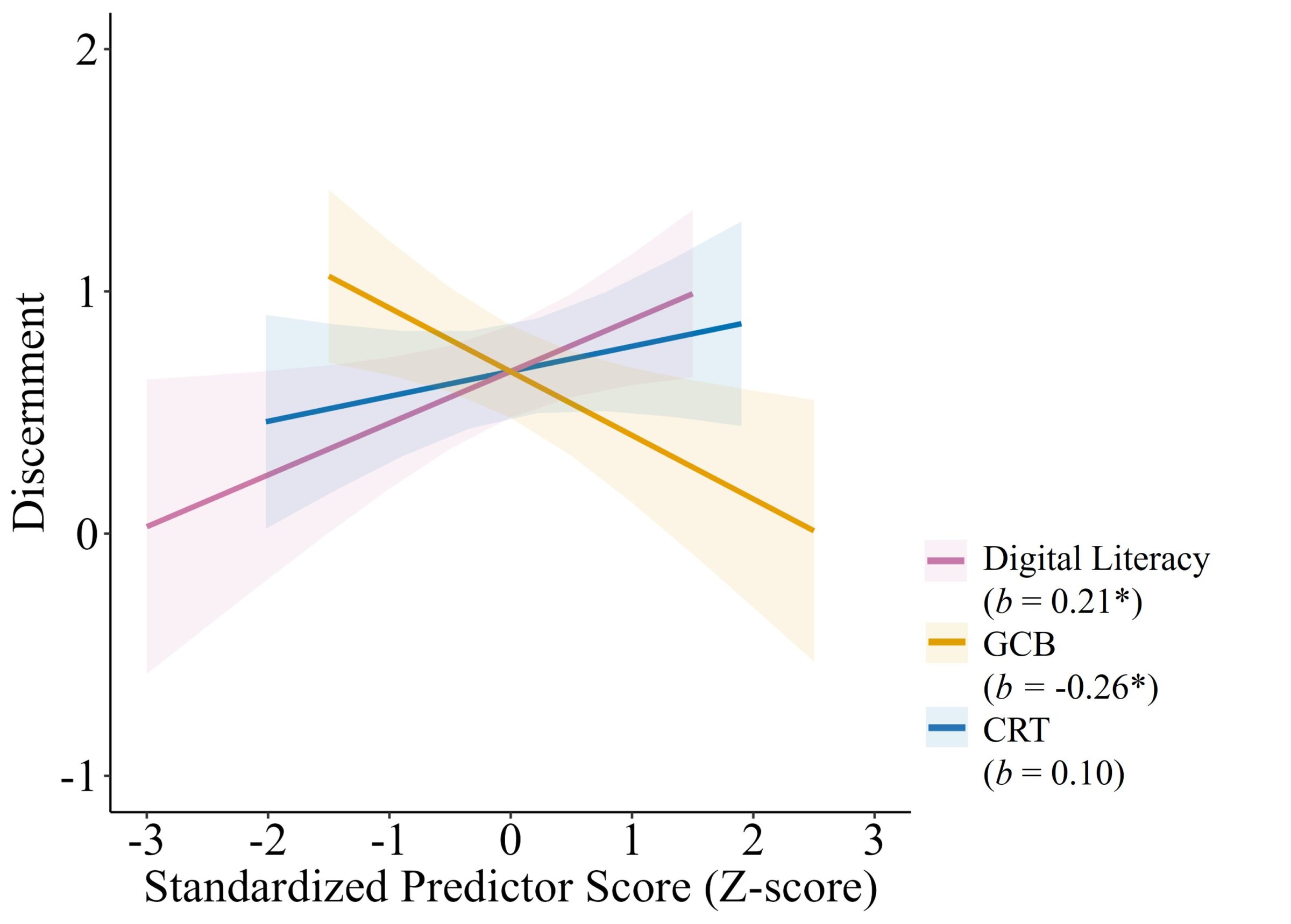

Our results showed that individual levels of digital literacy are positively correlated with headline discernment, while a greater tendency to hold conspiracy beliefs is related to decreased discernment. These findings are promising and suggest that institutions can focus on expanding the reach of current interventions aimed at improving digital literacy (e.g., integrating digital literacy courses into school curricula), which may be more practically feasible than developing and testing new interventions specifically tailored to AI-generated visual misinformation. Additionally, our findings suggest that existing interventions targeted at reducing conspiracy beliefs may improve detection of false headlines accompanied by AI-synthesized images, thereby extending the established benefits of such interventions. This broader efficacy could strengthen the case for their wider implementation by social media platforms, educational institutions, and governmental agencies. By demonstrating utility beyond conspiracy-related content, these interventions may be positioned as versatile tools for enhancing misinformation resilience across multiple formats and modalities. Despite prior associations between analytical thinking and headline accuracy discernment (Pennycook & Rand, 2021), we found that analytical thinking (as measured by the Cognitive Reflection Test) was not related to discernment. Therefore, if practitioners aim to implement existing interventions to enhance discernment between AI-synthesized and authentic image‑headline pairs, those targeting digital literacy and reducing conspiracy beliefs should take precedence over interventions designed solely to increase analytical thinking.

Findings

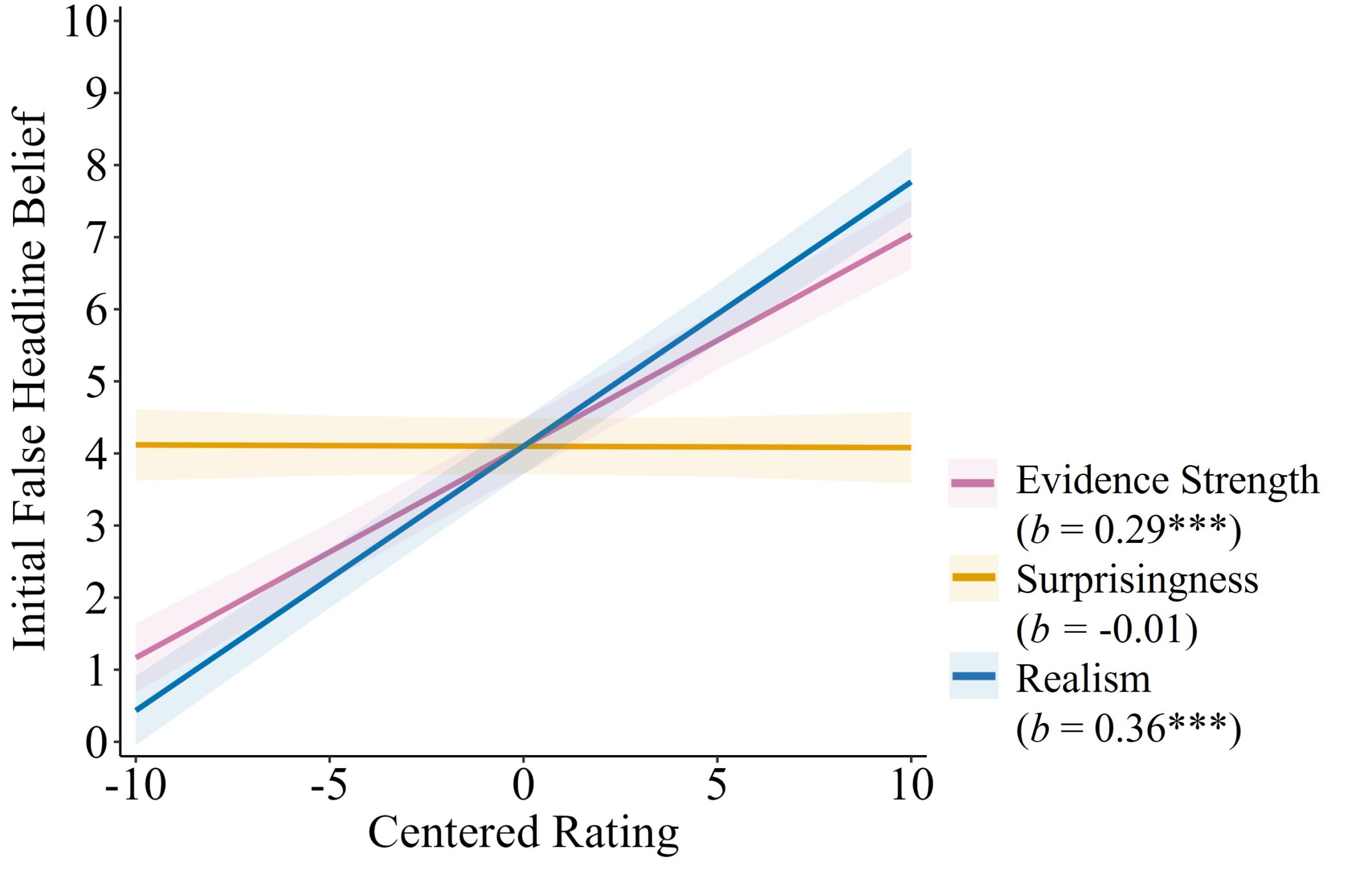

Finding 1: People are more susceptible to false headlines with realistic and probative (i.e., providing strong evidence) images.

We first examined how image properties influence initial belief in false headlines using a model with initial false headline belief as the outcome variable, centered values of realism, and evidence strength and image surprisingness as predictors. To account for repeated measures, we included participant and headline as random intercept effects. As seen in Figure 1, realism (b = 0.36, SE = 0.01, p < .001) and evidence (b = 0.29, SE = 0.01, p < .001) are positive predictors of initial belief in headlines. Surprisingness does not predict initial belief (b = -0.01, SE = 0.02, p = .688). This suggests that images that were perceived as more realistic and more probative are associated with increased belief.

Finding 2: Corrections reduce belief in false headlines.

Before examining how properties of images influence belief reduction, we first verified that corrections reduced initial beliefs in false headlines using a model with belief as the outcome variable and phase (initial and immediate post-correction) as a predictor. To account for repeated measures, we included random intercept effects of participant and headline. Compared to initial beliefs (M = 4.14, 95% CI = 4.05, 4.23), belief in false headlines is lower in the immediate post-correction phase (M = 2.13, 95% CI = 2.05, 2.22), b = -2.01, SE = 0.05, p < .001, indicating that corrections successfully reduce beliefs in false headlines.

Finding 3: Properties of images are not related to post-correction belief reduction in headlines or memory for corrections.

We next investigated whether properties of images are linked to post-correction belief reduction. We used a model with post-correction beliefs as the outcome variable, centered values of realism, evidence strength, and image surprisingness as predictors, with initial belief and ratings of surprise to corrections as covariates. To account for repeated measures, we included random intercept effects of participant and headline. We found that neither realism (b = 0.02), evidence strength (b = 0.01), nor image surprisingness (b = 0.01) significantly predict post-correction belief in false headlines (ps > .080).

Using the same model but with memory for corrections as the outcome variable, we found that, again, neither realism (b = -0.01), evidence strength (b = -0.00), nor image surprisingness (b = -0.01) predict memory for corrections (ps> .504). In sum, the properties of images do not seem to be related to belief reduction or memory for corrections.

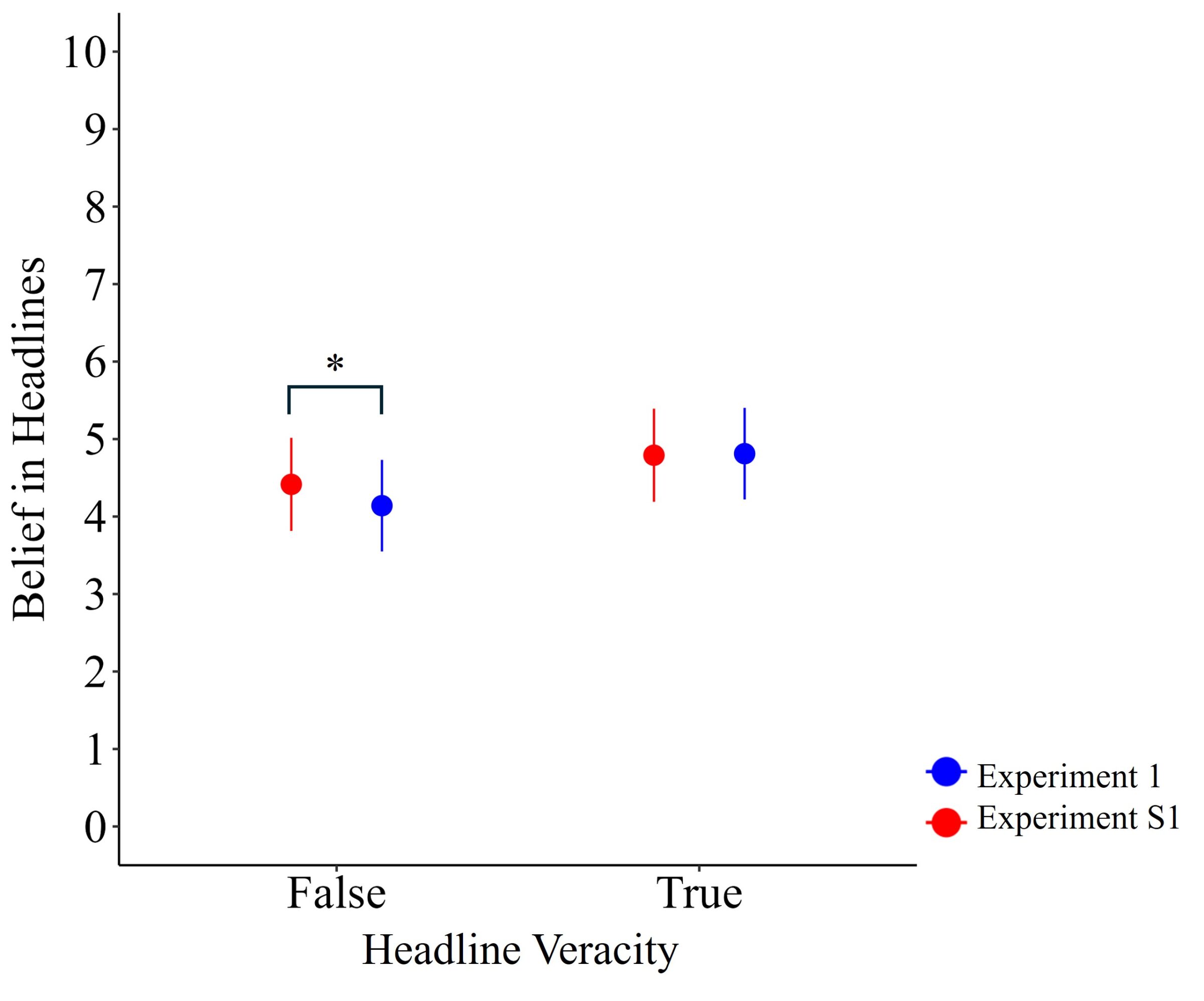

Finding 4: Rating image properties selectively decreases belief in false headlines.

To examine the effect of rating image properties on subsequent belief ratings, we conducted supplementary Experiment S1 (n = 150), in which a new group of participants rated belief in the same headlines without first rating properties of images (Appendix A). We used a model with initial belief in headlines as the outcome variable and experiment and headline veracity as predictors. To account for repeated measures, we included random intercept effects of participant and headline. Headline veracity (b = 0.52, SE = 0.41, p = .210) and experiment (b = -0.13, SE = 0.13, p = .316) do not significantly predict belief in headlines, but there was a significant interaction (b = 0.29, SE = 0.09, p < .001). As seen in Figure 2, participants in Experiment S1 (M = 4.41, 95% CI = 4.31, 4.52) have higher beliefs than those in Experiment 1 (M = 4.14, 95% CI = 4.05, 4.23) in false headlines, b = 0.28, SE = 0.13, p = .041. Belief in true headlines does not differ between Experiment 1 (M = 4.81, 95% CI = 4.71, 4.90) and S1 (M = 4.78, 95% CI = 4.68, 4.89), b = -0.02, SE = 0.13, p = .882. This suggests that completing ratings of image realism, surprisingness and evidence strength selectively decreases beliefs in false headlines.

Finding 5: Greater digital literacy and lower levels of conspiracist tendencies predict improved accuracy discernment.

Finally, we examined whether individual differences predict initial discernment between true and false headlines. Using a model with discernment (belief in true headlines minus belief in false headlines) as the outcome variable, and z-scored Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT), Generic Conspiracist Beliefs (GCB) and digital literacy scores as predictors (Figure 3), we found that greater GCB scores predict lower discernment (β = -0.26, SE = 0.10, p = .011), and greater digital literacy scores predict increased discernment (β = 0.21, SE = 0.10, p = .030), while CRT scores did not predict discernment, (β = 0.10, SE = 0.10, p = .304).

The full regression results are provided in Appendix B. We tested all prior findings with a sample that excluded participants who failed any attention checks and found results with the same direction and significance (see Appendix C). Additionally, possible differences in image-text co-reference (i.e., images may depict headline content to varying extents) may have influenced our results. Therefore, we defined co-reference as the proportion of words that are shown in the accompanying image and re-ran the analyses with this covariate, which yielded results with the same direction and significance (see Appendix D).

Methods

The experiment sought to answer the following research questions:

- Is realism, evidence strength and surprisingness of AI-synthesized images related to belief in false headlines?

- Are these properties of AI-synthesized images related to post-correction belief reduction and memory for corrections?

- How does rating these properties of images influence subsequent belief in false headlines?

- Are individual differences in digital literacy, conspiracist beliefs, and analytical thinking related to headline accuracy discernment?

Procedures

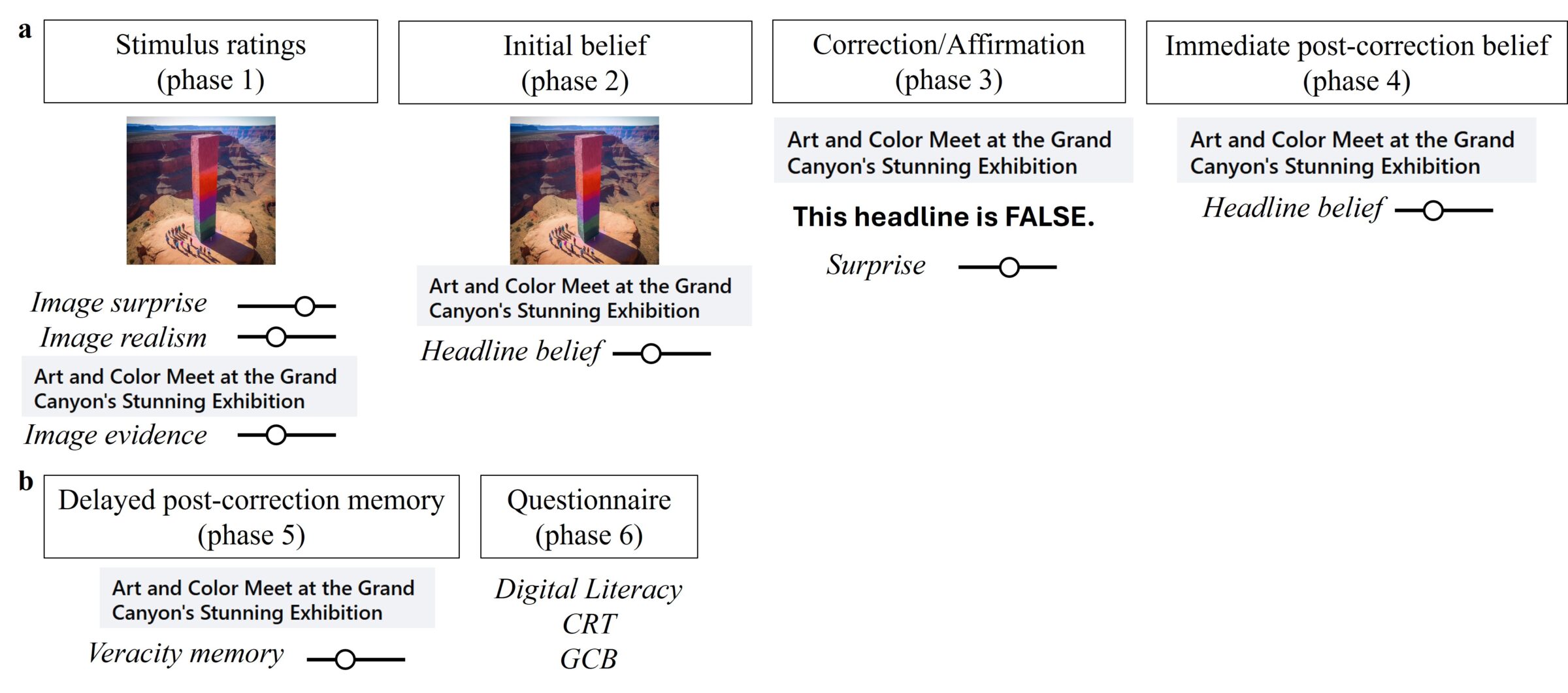

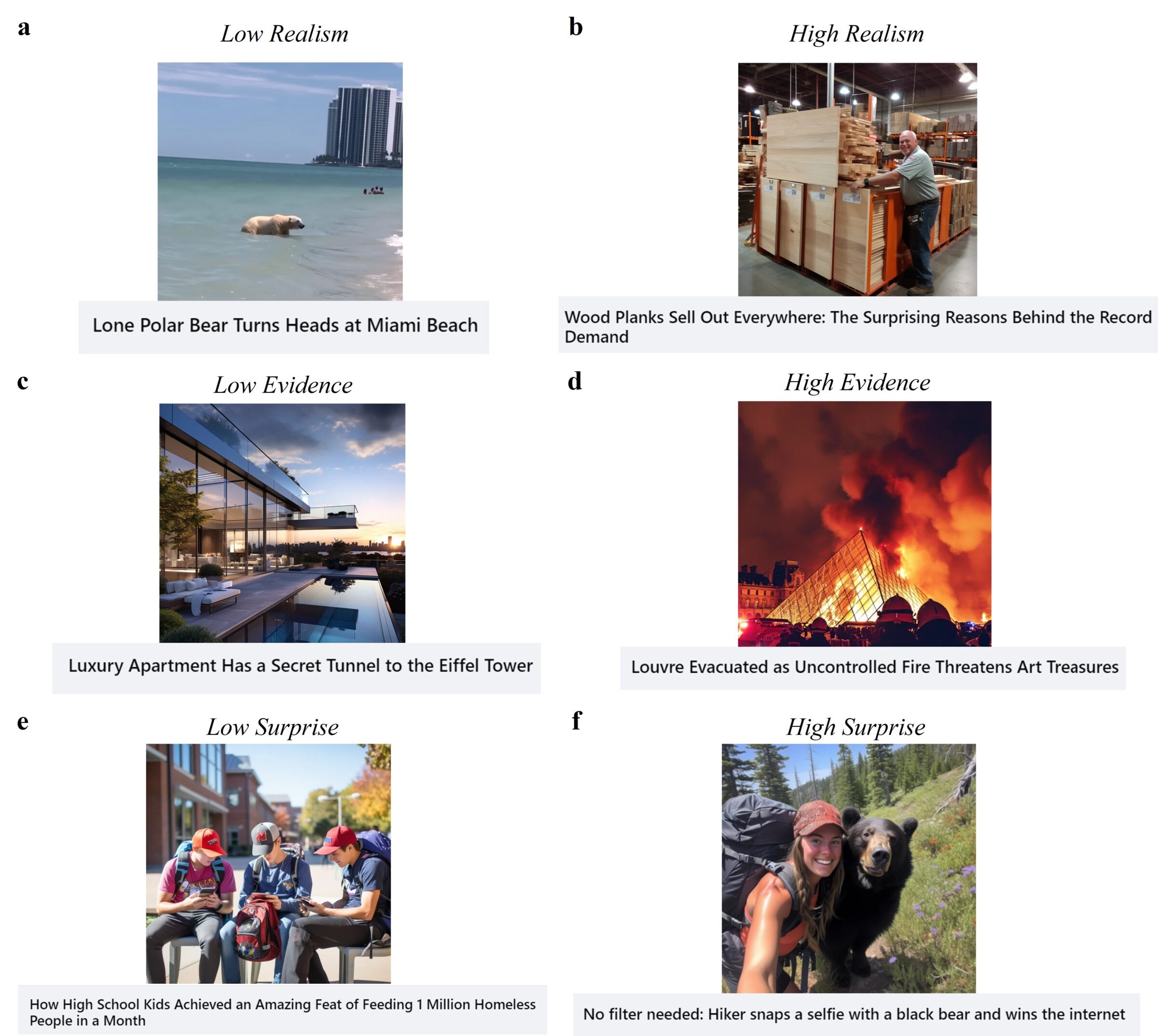

Stimulus ratings (phase 1):First, participants were instructed to rate how surprising and realistic images were, and how much evidence the image provided to a headline. Participants viewed 40 image-headline pairs individually in a random order. In each trial, they first saw an unlabeled real or AI-generated image and rated how surprising and realistic it was. Then, they saw the corresponding headline for that image and rated how much evidence the image provided to the headline.

Initial belief (phase 2):Participants were then told that they would see the same headlines again and rate how much they believed them. They then saw the same 40 headline-image pairs individually in a random order and rated their belief in the contents of the headline. We chose to include initial belief ratings in a separate task from phase 1 to minimize the effects of completing stimulus ratings on beliefs.

Correction/Affirmation task (phase 3): Next, participants were told that they would receive corrections or affirmations to the headlines they previously viewed. Participants read corrections and affirmations to all 40 headlines in a randomized order and rated how surprised they were upon receiving this information. Headlines were shown without images alongside a label stating “this headline is TRUE” for true headlines, and “this headline is FALSE” for false headlines.

Immediate post-correction belief (phase 4): Participants were then told to rate whether they thought headlines were true or false based on the information they received in phase 3. They then saw all 40 headlines again without images in a random order and rated their belief in the headline.

Delayed post-correction memory (phase 5): After one week, participants were instructed to complete a memory test by trying to remember whether headlines were true or false based on corrections and confirmations presented one week ago. Participants viewed all 40 headlines again individually in a randomized order and rated whether they remembered if the headline was corrected or affirmed in phase 3 of the experiment. It is important to note that ratings in each phase used discrete sliders (on a scale from 0 to 10) instead of radio buttons, which may have introduced variability in participant responses due to potential ambiguity in scale interpretation.

Questionnaires (phase 6): Participants completed a battery of questionnaires, including a ten-item digital literacy scale (Hargittai, 2009), seven cognitive reflection test (CRT) questions (Oldrati et al., 2016; Thomson & Oppenheimer, 2016), and 15 questions from the Generic Conspiracist Beliefs scale (GCB) (Brotherton et al., 2013).

At the end of the experiment, participants were debriefed on the nature of the experiment. They then indicated which AI-generated and real images they had seen prior to the experiment. Trials containing these images were then excluded from analyses, as preregistered (18 AI-generated [0.4%] and 53 real [1.3%] trials excluded). For more details on the procedure, please refer to Appendix E.

Participants

After exclusions, the final sample included 212 participants from Prolific. We excluded participants if there were multiple submissions from the same user (n = 2), if there was a high likelihood of an automated submission, flagged by Qualtrics security measures (n = 7), if they provided more than 80% identical responses in the initial belief rating or immediate post-correction belief rating stage (n = 2), if they failed at least two out of three attention checks (i.e., the headline read “For this question, please rate 7 on the scale below. This is an attention check.”) on the first day of the experiment (n = 12), or if they did not return one week later for the second part of the experiment (n = 20). After exclusions, the final sample included 119 men and 92 women, and one who did not report their gender from Prolific (Mage = 42.4, SD = 13.6, range = 20 to 104 years old). Participants currently resided in the United States, spoke English as their first language, completed at least 10 prior submissions, and had an approval rating of at least 90% on Prolific.

Stimuli

We wrote our own false headlines to match the content of AI-generated images, which we took from a Reddit community dedicated to sharing AI generated images from the website Midjourney (reddit.com/r/midjourney). We chose images that emulated photographs in composition, content, and style, as they have the greatest potential to mislead. We found true headlines and corresponding real images online from reputable news sources, and we re-used some from on a previous study on the role of images in news (Smelter & Calvillo, 2020). We created both types of headlines to emulate the style of news headlines on Facebook to improve external validity (see Figure 5).

We pretested images to ensure a wide distribution of realism and evidence strength, and pretested headlines to ensure a wide distribution of believability. The final experiment contained 40 headline-image pairs (20 AI-generated images with false headlines and 20 real images with true headlines). Both false and true headlines contained news about animals, accidents, natural disasters, and strange phenomena. We avoided political and health-related topics in our headlines to minimize effects of prior attitudes on belief.

Topics

Bibliography

Brotherton, R., French, C. C., & Pickering, A. D. (2013). Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: The generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279

Diakopoulos, N., & Johnson, D. (2021). Anticipating and addressing the ethical implications of deepfakes in the context of elections. New Media and Society, 23(7), 2072–2098. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820925811

Dobber, T., Metoui, N., Trilling, D., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. (2021). Do (microtargeted) deepfakes have real effects on political attitudes? International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220944364

Guo, S., Swire-Thompson, B., & Hu, X. (2025). Specific media literacy tips improve AI-generated visual misinformation discernment. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-025-00648-z

Hargittai, E. (2009). An update on survey measures of web-oriented digital literacy. Social Science Computer Review, 27(1), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439308318213

Heley, K., Gaysynsky, A., & King, A. J. (2022). Missing the bigger picture: The need for more research on visual health misinformation. Science Communication, 44(4), 514–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470221113833

Karnouskos, S. (2020). Artificial intelligence in digital media: The era of deepfakes. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, 1(3), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1109/tts.2020.3001312

Oldrati, V., Patricelli, J., Colombo, B., & Antonietti, A. (2016). The role of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in inhibition mechanism: A study on cognitive reflection test and similar tasks through neuromodulation. Neuropsychologia, 91, 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.09.010

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(5), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007

Smelter, T. J., & Calvillo, D. P. (2020). Pictures and repeated exposure increase perceived accuracy of news headlines. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(5), 1061–1071. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3684

Ternovski, J., Kalla, J., & Aronow, P. (2022). Negative consequences of informing voters about deepfakes: Evidence from two survey experiments. Journal of Online Trust and Safety, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.54501/jots.v1i2.28

Thomson, K. S., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2016). Investigating an alternate form of the cognitive reflection test. Judgment and Decision Making, 11(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1930297500007622

Yaqub, W., Kakhidze, O., Brockman, M. L., Memon, N., & Patil, S. (2020, April 21). Effects of credibility indicators on social media news sharing intent. In CHI ’20: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–14). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376213

Funding

X.H. discloses support for the research from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China STI2030-Major Projects (No. 2022ZD0214100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32171056), and the General Research Fund of Hong Kong Research Grants Council (No. 17614922).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

This research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong (EA210341). Participants provided informed consent prior to completing the study. Gender information was determined from demographic information collected and defined by Prolific.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OJKYPQ. Pre-registration is available at: https://osf.io/fw863

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Briony Swire-Thompson for providing valuable comments on the manuscript and Dr. Ziqing Yao for assisting with data analysis.