Peer Reviewed

How spammers and scammers leverage AI-generated images on Facebook for audience growth

Article Metrics

15

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Much of the research and discourse on risks from artificial intelligence (AI) image generators, such as DALL-E and Midjourney, has centered around whether they could be used to inject false information into political discourse. We show that spammers and scammers—seemingly motivated by profit or clout, not ideology—are already using AI-generated images to gain significant traction on Facebook. At times, the Facebook Feed is recommending unlabeled AI-generated images to users who neither follow the Pages posting the images nor realize that the images are AI-generated, highlighting the need for improved transparency and provenance standards as AI models proliferate.

Research Questions

- How are profit and clout-motivated Page owners using AI-generated images on Facebook?

- When users see AI-generated images on Facebook, are they aware of the synthetic origins?

Essay Summary

- We studied 125 Facebook Pages that posted at least 50 AI-generated images each, classifying them into spam, scam, and other creator categories. Some were coordinated clusters run by the same administrators. As of April 2024, these Pages had a mean follower count of 146,681 and a median of 81,000.

- These images collectively received hundreds of millions of exposures. In Q3 2023, a post with an AI-generated image was among Facebook’s top 20 most viewed posts, with 40 million views and more than 1.9 million interactions.

- Spam Pages adopted clickbait tactics, directing users to off-platform content farms and low-quality domains. Scam Pages attempted to sell non-existent products or obtain users’ personal details.

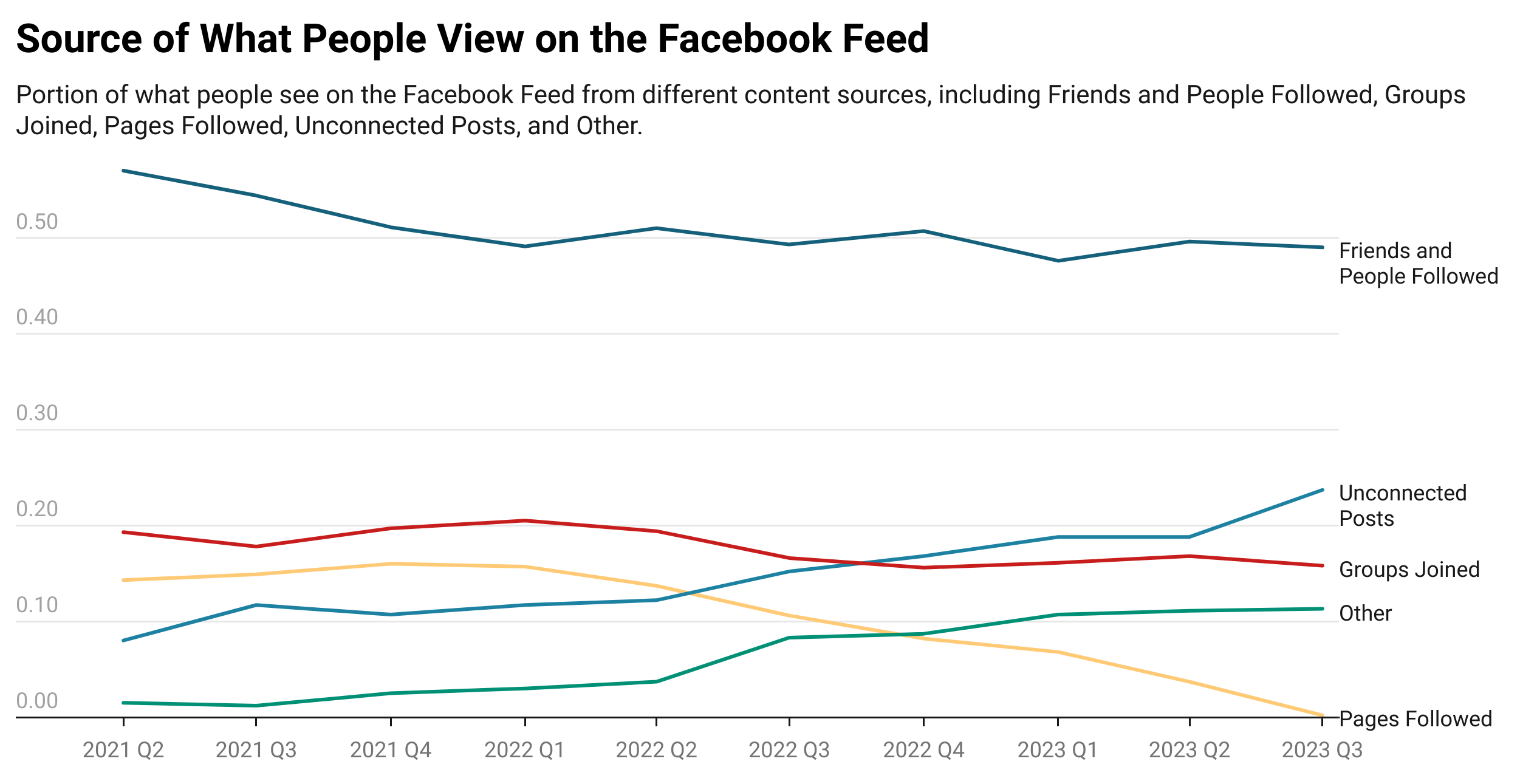

- The Facebook Feed (formerly “News Feed”) shows users AI-generated images even when they do not follow the Pages posting those images. We suspect this is because the algorithmic Feed promotes content that is likely to generate engagement. Facebook has increased the percentage of “unconnected posts” (posts that did not come from friends, Pages people followed, or Groups they were a part of) in users’ Feeds over the last three years.

- Comments on the images suggest that many users are unaware of their synthetic origin, though a subset of comments include text or infographics alerting others and warning of scams. Viewer misperceptions highlight the importance of labeling and transparency measures moving forward.

- Some of the Pages in our sample used known deceptive practices, such as Page theft or takeover, and exhibited suspicious follower growth.

Implications

With the diffusion of new generative AI tools, policymakers, researchers, and the public have expressed concerns about impacts on different facets of society. Existing work has developed taxonomies of misuses and harm (Ferrara, 2024; Weidinger et al., 2022) and tested the potential of AI tools for generating instructions for biological weapons (Mouton et al., 2024), propaganda (Goldstein et al., 2024; Spitale et al., 2023), and phishing content (Grbic & Dujlovic, 2023). A significant portion of this literature is theoretical or lab-based and focused on political speech, such as impacts on elections, threats to democracy, and shared capacity for sensemaking (Seger et al., 2020).

And yet, even in the realm of the political, the tactics of manipulators have long been previewed by those with a different motivation: making money. Spammers and scammers are often early adopters of new technologies because they stand to profit during the time gap between when technology makes novel, attention-capturing tactics possible and when defenders recognize the dynamics and come up with new policies or interventions to minimize their impact (e.g., Goldstein & DiResta, 2022; Metaxas & DeStefano, 2005). Recall the Macedonian teenagers behind the high-profile “fake news” debacles of 2016: Investigative reports found they used eye-catching content—promoted by Facebook’s recommendation and trending algorithms—to drive users to off-platform websites where they would collect advertising revenue via Google Adsense (e.g., Hughes & Waismel-Manor, 2021; Subramanian 2017).

While the misuse of text-to-image and image-to-image models in politics is worthy of study, so are deceptive, non-political applications. Understanding misuse can shape risk analysis and mitigations. In this article, we show that images from AI models are already being used by spammers, scammers, and other creators running Facebook Pages and are, at times, achieving viral engagement. For the purposes of this study, we describe Pages as “spam” if they post low-effort (e.g., AI-generated or stolen) content at high frequencies and (a) use clickbait tactics to drive people to an outside domain or (b) have inauthentic follower growth (e.g., from fake accounts). We categorized Pages as “scam” if they (a) deceive followers by stealing, buying, or exchanging Page control, (b) falsely claim a name, address, or other identifying feature, and/or (c) sell fake products. Our “other creator” category includes Pages that post AI-generated images at high frequency and are not transparent about the synthetic origin of content, but we do not have clear evidence of manipulative behavior.

We studied 125 spam, scam, and other creator Facebook Pages that shared 50+ AI-generated images to capture the attention of Facebook users. Many of these Pages formed clusters, such as six Pages with more than 400,000 collective followers that declared themselves affiliated with the “Pil&Pet Corporation” in the Intro section of their Pages. The Pil&Pet Pages posted AI-generated images with similar captions and all had Page operators from Armenia, the United States, and Georgia. Some Pages we studied did not declare a mutual affiliation, but posted on highly similar topics, recycled posts, and co-moderated Facebook Groups or shared links to the same domains. Other Pages were not clearly connected to others in the list but used highly similar captions, identical generated images, or images on similar themes. A number of Pages, for example, posted AI-generated images of log cabins. At times, these AI-generated images were recommended to users via Facebook’s Feed (including in our own Feeds). The posts are not transparent about the use of AI and many users do not seem to realize that they are of synthetic origin (Koebler, 2023). Facebook confirmed in a statement to us by email that they have “taken action against those engaged in inauthentic behavior, and demoted the clickbait websites under [their] Content Distribution Guidelines.”1The full statement by Meta via email to the authors on April 10, 2024: “We welcome more research into AI and cross-platform inauthentic behavior since deceptive efforts rarely target only one platform. We’ve reviewed the pages in this report and have taken action against those engaged in inauthentic behavior, and demoted the clickbait sites under our Content Distribution Guidelines. We’re also continuing to work with industry partners on common technical standards for identifying and labeling AI-generated content.”The full statement by Meta via email to the authors on April 10, 2024: “We welcome more research into AI and cross-platform inauthentic behavior since deceptive efforts rarely target only one platform. We’ve reviewed the pages in this report and have taken action against those engaged in inauthentic behavior, and demoted the clickbait sites under our Content Distribution Guidelines. We’re also continuing to work with industry partners on common technical standards for identifying and labeling AI-generated content.”

Consequences and recommendations

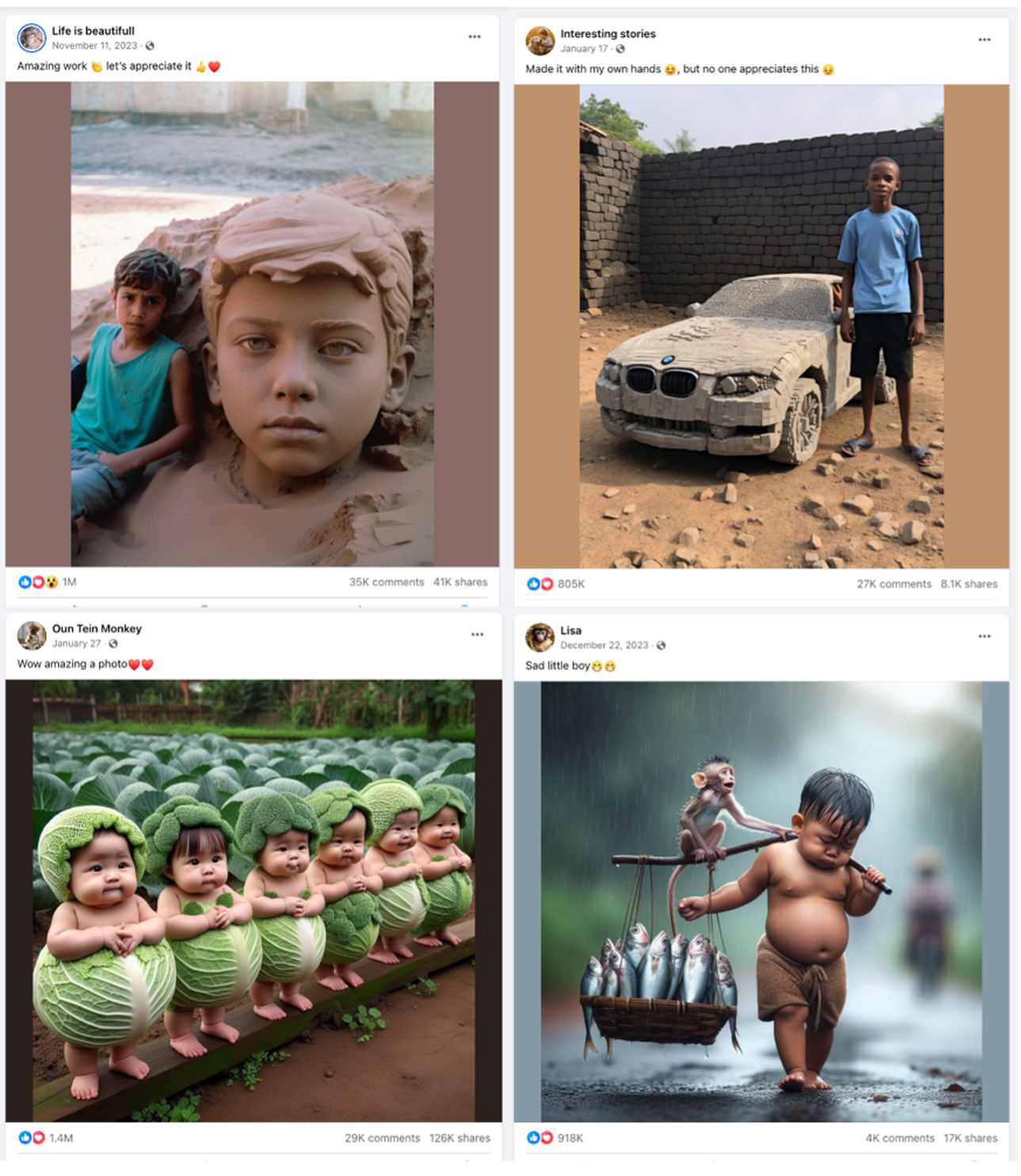

The Pages we studied may produce direct and indirect negative impact. In terms of direct consequences, we observed unambiguously manipulative behaviors from some of the Page operators, such as Page/account theft and leveraging batches of inauthentic followers to enhance their legitimacy or engage in discourse with content viewers. AI-generated content appears to be a boon for spam and scam actors because the images are easy to generate, often visually sensational, and attract engagement. In terms of indirect consequences, most of the AI-generated images did not include an indication of their synthetic origin. Comments by Facebook users often suggested that they did not recognize the images were fake—congratulating, for example, an AI-generated child for an AI-generated painting. Scam accounts occasionally engaged with credulous commenters on the posts, both in Pages and Groups, at times seeking personal information about them or offering to sell them products that do not exist. The increasing complexity of distinguishing between real and synthetic content online will likely further exacerbate issues with trust in media and information.

To grapple with deceptive AI-generated content, interventions could target at least three different stages: (1) reducing the likelihood that deceptive content reaches end users without notice, (2) decreasing the impact of deceptive content that does reach end users, and (3) measuring real-world use and impact of deceptive AI-generated content on social media platforms. We describe several specific mitigations—improved detection methods, education, and impact assessments—that fall under these three stages, respectively, while recognizing that other approaches can also contribute.

First, social media companies should invest resources in improving detection of scams as well as AI-generated content. For the latter, collaborations between AI developers, social media platforms, and external researchers may be useful for ensuring that the most robust detection mechanisms are deployed in practice. Platforms should test the effect of different interventions for indicating that content is AI-generated (including labeling images they detect, requiring users to proactively label, and rolling out watermarking techniques) (Bickert, 2024) and researchers should investigate whether tech companies are true to the voluntary commitments announced at the 2024 Munich Security Conference (e.g., “attaching provenance signals to identify the origin of content where appropriate and technically feasible”) (Munich Security Conference, 2024). Labeling AI-generated content can decrease deception of social media users, but it could come at a cost if there are high false-positive or false-negative rates.

Second, the media, and AI generation tool creators themselves, should help the public understand AI image generation tools in a manner that is digestible and not sensational. This could include Public Service Announcements that teach that AI-generated images can look photorealistic. Such announcements should learn from recent work on inoculation theory (e.g., Roozenbeek, 2022) and teach proactive user strategies (e.g., lateral reading). This may improve social media users’ discernment of AI-generated images that are implausible and increase the likelihood that they fact-check images against other sources (as it will often not be obvious when seemingly photorealistic images are AI-generated). This should be complemented by teaching people general digital literacy best practices, such as Mike Caufield’s “SIFT” method: Stop, Identify the source, Find better coverage, and Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original context (Caufield, 2019).

Third, researchers should contribute to understanding the effects of AI-generated content on broader information landscapes. Although our study focuses specifically on Facebook, other platforms also face challenges related to AI-generated content. Research has investigated the use of deceptive AI-generated profile pictures on Twitter (Yang et al., 2024) and LinkedIn (Goldstein & DiResta, 2022), and journalists have documented the use of new generative AI tools for spam on TikTok (Koebler, 2024b), scam books on Amazon (Limbong, 2024), and other applications. Accumulation of additional studies through incident databases (e.g., Dixon & Frase, 2024; Walker et al., 2024) can contribute to cross-platform, comparative analysis—such as whether and how the execution of AI-enabled harms varies by affordances of platforms. Studies of real-world use can inform which specific applications require prioritization for detection and educational efforts described above. Another line of research can examine how labeling content as AI-generated affects perceptions of unlabeled content (Jakesch et al., 2019) or interview individuals behind the deceptive use of AI-generated content on social media to better understand their motivations and perceptions of ethics.

Findings

Finding 1: Spammers, scammers, and other creators are posting unlabeled AI-generated images that are gaining high volumes of engagement on Facebook. Many users do not seem to recognize that the images are synthetic.

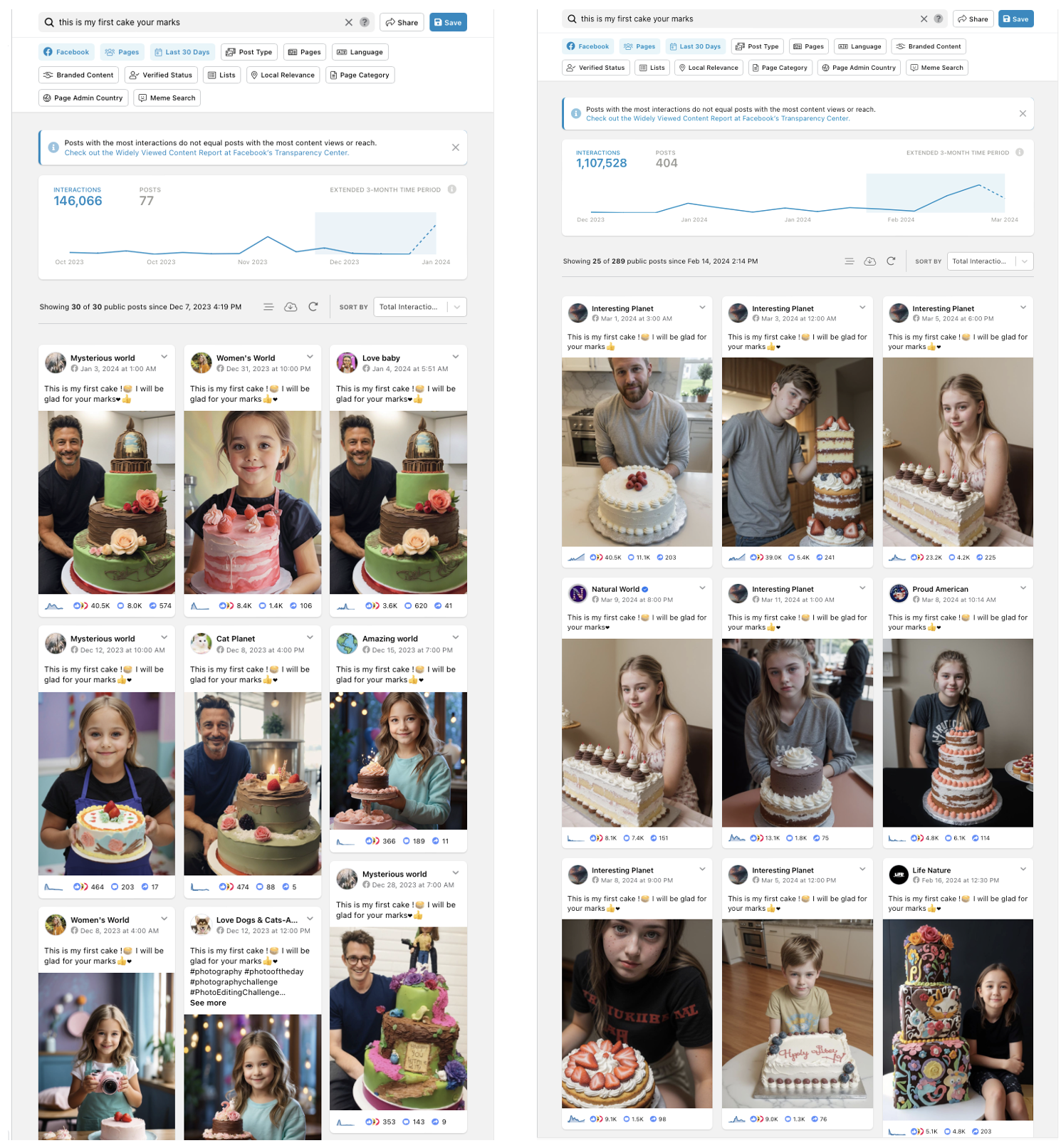

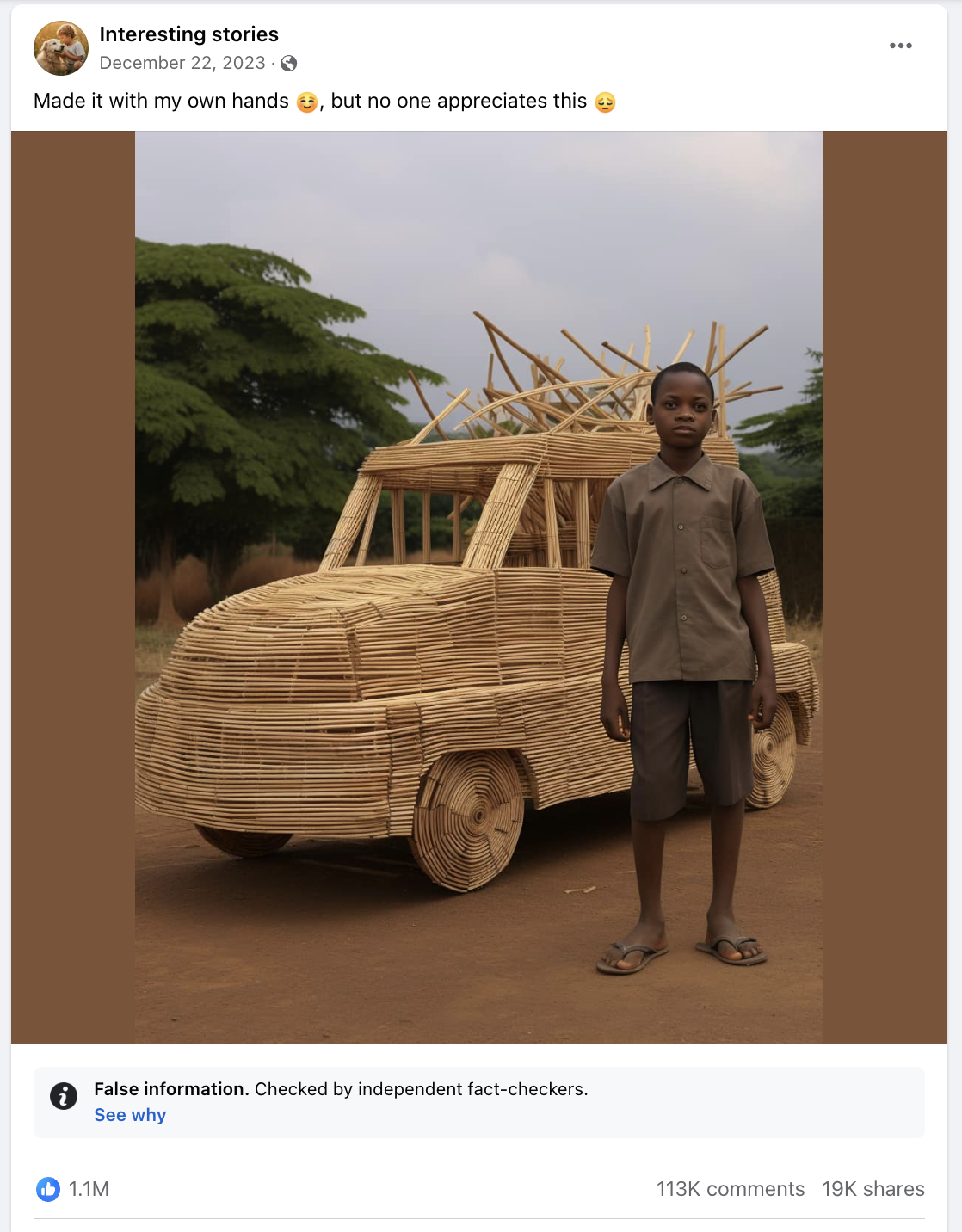

Unlabeled AI-generated images from the Pages we studied amassed a significant number of views and engagements. One way that we discovered Pages deceptively using AI-generated images was by observing repeated caption text across Pages—even Pages that were seemingly unconnected. For example, AI-generated content of old people, amputees, and infants often contained the phrase “No one ever blessed me” in the caption. AI-generated images of people alongside their supposed woodworking or drawings were captioned with variants on “Made it with my own hands”; neither the person depicted nor the art is real. Phrases such as “This is my first cake! I will be glad for your marks” explicitly solicit comment feedback (see Figure 1). Oftentimes these posts received comments of praise. Sometimes the post text made little sense in context; an AI-generated image of Jesus rendered as a crab worshiped by other crabs also proudly declared “Made it with my own hands!” and received 209,000 reactions and more than 4,000 comments (see Figure 2).

Common themes for content across the Pages we studied included AI-generated houses or cabins (43 Pages), AI-generated images of children (28 Pages), AI-generated wood carvings (19 Pages), and AI-generated images of Jesus (13 Pages). We provide examples of other AI-generated images posted by Pages in the dataset with high levels of engagement in Figure 3.

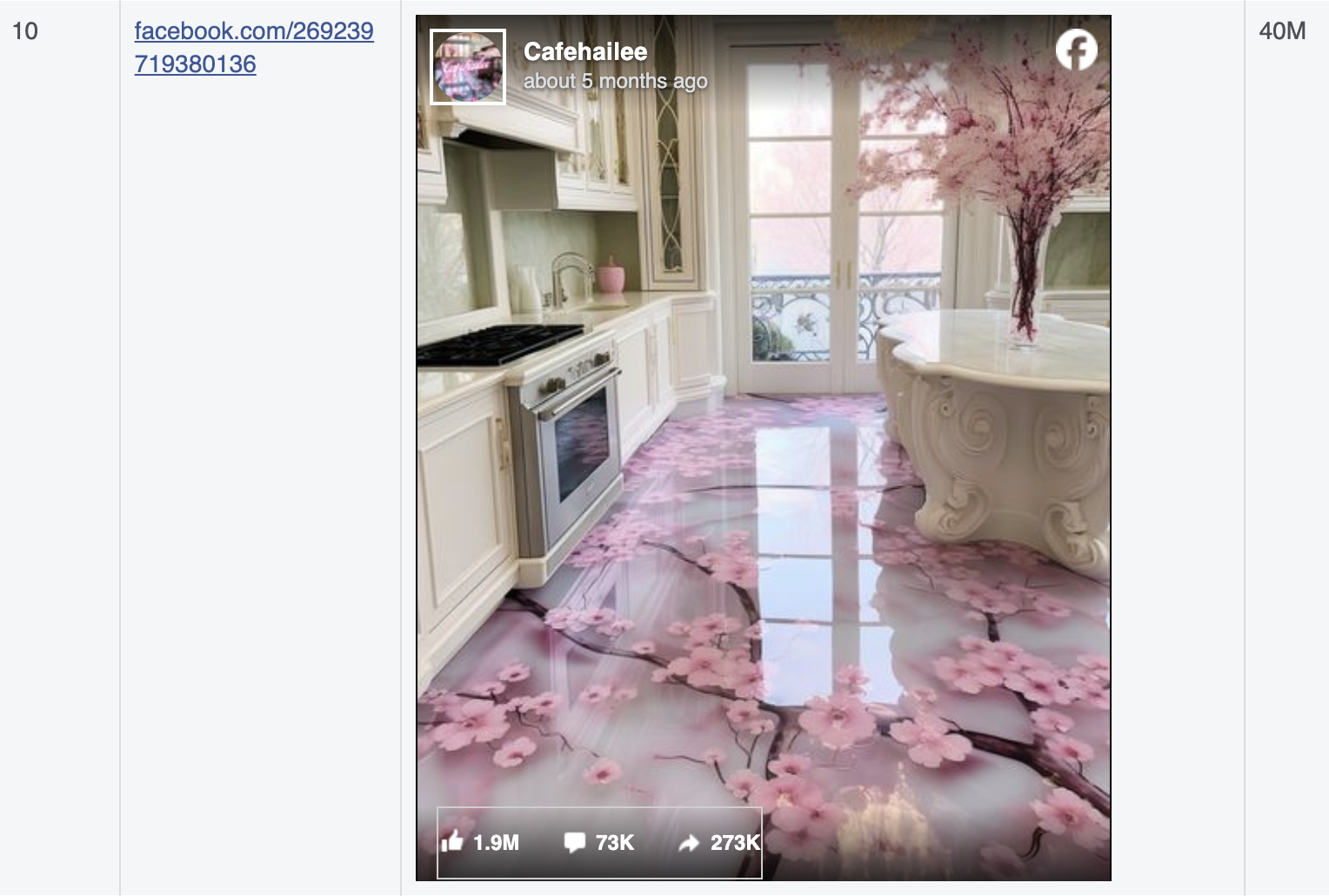

While researchers typically can see the number of engagements a post has (the sum of reactions, comments, and reshares), they do not have access to the number of views. However, view counts do appear for the 20 most viewed pieces of content in a given quarter, available via Facebook Transparency’s Center. One of the 10 most viewed posts in Q3 2023 was an unlabeled AI-generated image from a Page that transitioned from a cooking Page to one showing AI-generated images of kitchens (Figure 4).

Finding 2: The Facebook Feed at times recommends unlabeled AI-generated images to users who do not explicitly follow the Page posting the content.

We suspect these high levels of engagement are partially driven by the Facebook recommendation algorithm.2In 2022, Alex Heath reported on an internal memo by Facebook President Tom Allison about planned changes to the algorithm that would “help people find and enjoy interesting content regardless of whether it was produced by someone you’re connected to or not.” According to Heath, it was clear to Meta that to compete with TikTok, it had to compete with the experience of TikTok’s main “For You” Page, which shows people content based on their past viewing habits and anticipated preferences (independent of whether the user follows the creator’s account). Meta’s quarterly “Widely Viewed Content Report: What People See on Facebook” includes a section that breaks out where posts in Feed come from (e.g., from Groups people joined; content their friends shared; sources they aren’t connected to, but Facebook thinks they might be interested in, etc.).3We pulled the portion of Feed views from different sources, reported each quarter from Q2 2021 (when Facebook began publishing it) through article drafting in Q3 2023. As shown in Figure 5, the portion of content views from “unconnected posts” (posts from sources users are not connected to) from Facebook algorithm recommendations rose dramatically from 8% in Q2 2021 to 24% in Q3 2023.

After we conducted preliminary research, we began to see an increasing percentage of AI-generated images in our own Feeds, despite not following or liking any of the Pages posting AI-generated images. The algorithm likely expected us to view or engage with AI-generated images because we had clicked on others in the past. Two colleagues who reviewed our work reported that they were shown AI-generated images in their Feed before they even began investigating, and we observed a number of social media users claiming large influxes of AI-generated images in their Facebook Feeds (Koebler, 2024c). For example, Reddit users are discussing their Facebook Feeds with comments such as “Facebook has turned into an endless scroll of Midjourney AI photos and virtually no one appears to have noticed.”

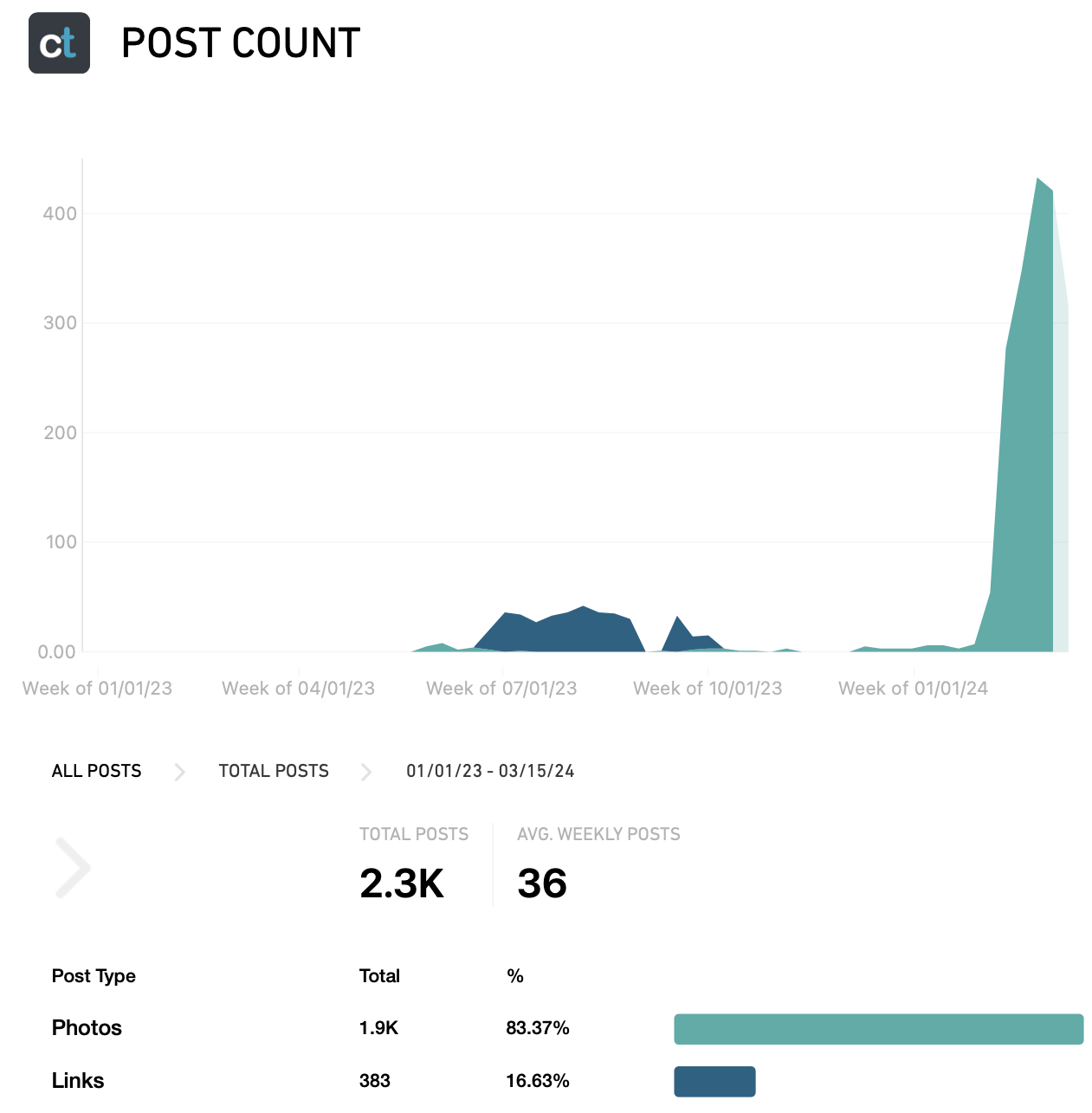

Finding 3: Scam and spam Pages leveraging large numbers of AI-generated images are using well-known deceptive practices, such as Page theft or repurposing, and exhibit suspicious follower growth.

Research into social media influence dynamics has observed that Page growth is a common strategic goal. Obtaining a Page with an existing following provides a ready-made audience that can be monetized. A large follower count increases the perceived credibility of a Page (Phua & Ahn, 2016), so fake engagement is also used to create this perception. Some of the Facebook Pages we analyzed used tried-and-true tactics along these lines: 50 had changed their names, often from an entirely different subject, and some displayed a massive jump in followers after the name change (but prior to new activity that would organically have produced that follower spike).

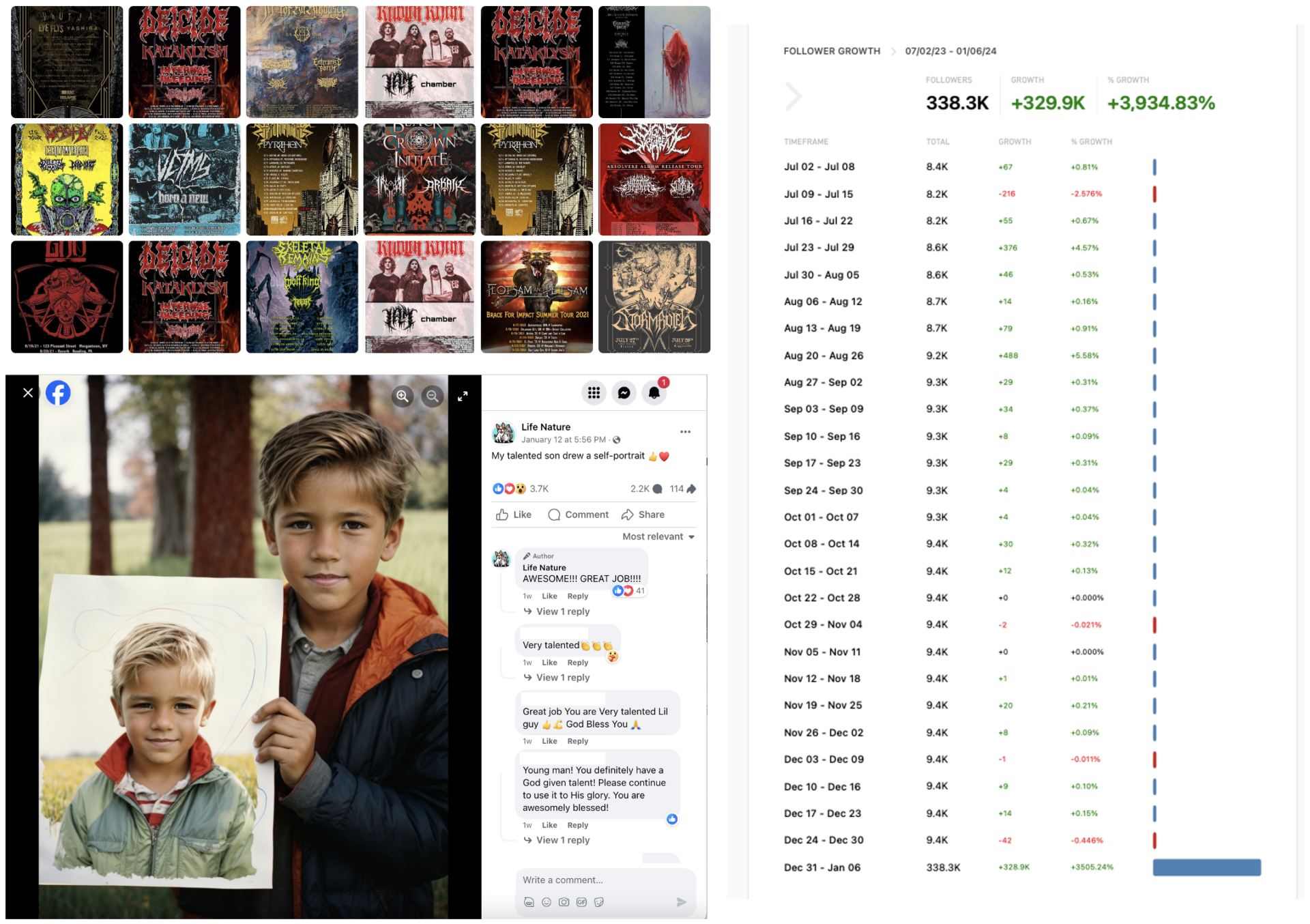

Take, for example, the Page “Life Nature.” The Page was first created on December 9, 2011, with the name “Rock the Nation USA,” and it appears to be the Page of a real band posting fliers for the traveling band with information about upcoming concerts. On December 29, 2023, the Page changed its name to “Life Nature” and began posting AI-generated images (among photos taken from other parts of the Internet). Whereas the touring band had ~9,400 followers, a number which had remained consistent from July 2023 to December of that year, following the name change the Page acquired 300,000 followers (December 31 to January 6). The second post after the name change received more than 32,000 likes and 17,000 comments. Figure 6 shows changes in content from band posters to AI-generated content. A booking agent for the band told 404 Media’s Jason Koebler, who found the Page as part of his own investigation, “we found out about the page being hacked towards the end of December. No idea how it happened, unfortunately, as I was the only admin and my personal profile is still intact. Appreciate you trying to support the cause” (Koebler, 2024a). Figure 6 shows the increase in follower growth. Since our analysis, the Page is no longer live on Facebook.

Other examples of Facebook Pages that posted a large number of AI-generated images but were either stolen or repurposed include “Olivia Lily” (formerly a church in Georgia), “Interesting stories” (formerly a windmill seller), and “Amazing Nature” (formerly equine services). One such Page was stolen from a high school band in North Carolina, per NBC reporting (Yang, 2024).

Spam Pages largely leveraged the attention they obtained from viewers to drive them to off-Facebook domains, likely in an effort to garner ad revenue. They would post the AI-generated image often using overlapping captions as described in Finding 1, then leave the URL of the domain they wished users to visit in the first comment. For example, a cluster of Pages that posted images of cabins or tiny homes pointed users to a website that purportedly offered instructions on how to build them. Other clusters used AI-generated or enhanced images of celebrities, babies, animals, and other topics to grab attention and then directed users to heavily ad-laden content farm domains—some of which themselves appeared to consist of primarily AI-composed text. An examination of the posting dynamics of several Pages in our data set—those created prior to easily-available generative AI tools—suggested that they both increased their posting volume and also transitioned from posting primarily clickbait links to their domains to posting attention-grabbing AI-generated images (see Figure 7). This is potentially due to the perception that the recommendation engine was likely to privilege one content type over another.

Scam Pages used images of animals, homes, and captivating designs as well, but often implied that they sold the product. Users that appeared to be fake (new accounts, stolen and reversed profile photos) engaged with commenters about the potential to purchase the product or obtain more information.

These spam and scam behaviors were distinct from other high-posting-frequency Pages that appeared to be capitalizing on AI-generated image content for audience growth, including some that ran political ads which were not demonstrably manipulative.

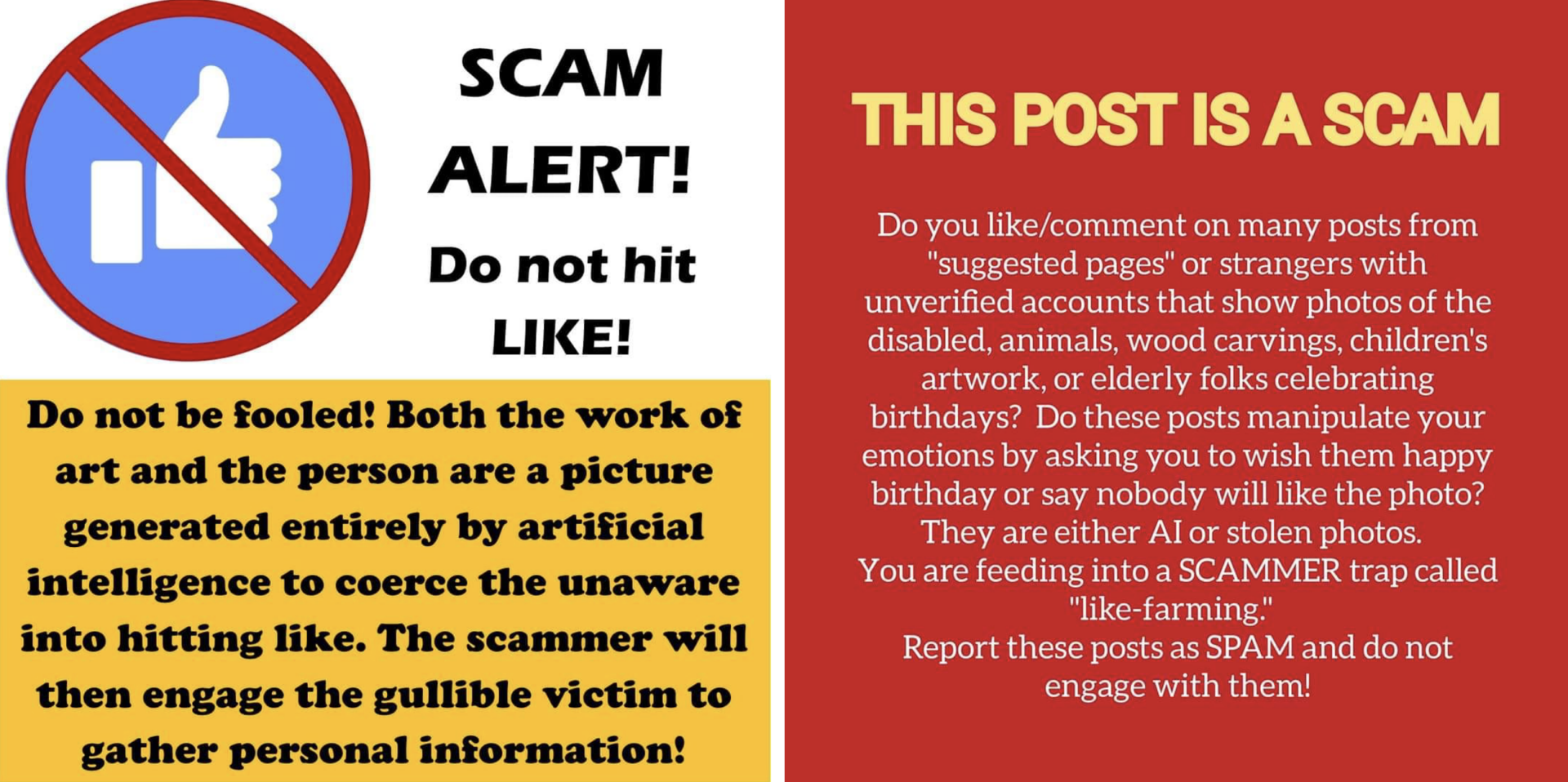

Finding 4: A subset of Facebook users realized that the images were AI-generated and took steps to warn other users.

While most comments on the AI-generated images were unrelated to the artificial nature of the images, some users who encountered the images criticized them for manipulative content or suspicious behavior. For example, take the Page “Love Baby.” From November 2019 through June 2021, the majority of Reviews on the Page described positive experiences visiting a store in Maryland. They talked about the holidays and supporting local businesses. However, recent reviews mentioned the AI-generated content: “mostly Fake/AI” (November 20, 2023) or “all contents are AI GENERATED, so fake” (January 17, 2024). The change in reviews corresponds to a likely change in Page control, as the Page—which included profile pictures of Catonsville Mercantile—transitioned to posting AI-generated content in May 2023.

In addition to alerting others through reviews, users posted comments on photorealistic images from several Pages in our data set highlighting that the content is AI-generated. These comments occasionally included alert infographics explaining bad behavior on AI Pages writ large, including engaging in nefarious activities like identifying targets for scams.

During the time of our investigation, Meta announced its plan to roll out labeling of AI-generated images that it could detect (Clegg, 2024). A subsequent announcement put the target date for this effort at May 2024 (Bickert, 2024). However, as shown in Figure 9, we did find at least one image labeled as “False information” during our investigation. The label linked to an article from Congo Check highlighting that the image was AI-generated and engaging in comment-bait, or encouraging interaction to artificially increase engagement and reach (Watukalusu, 2024). The article cited the high number of engagements with the post; it was likely fact-checked because it went viral. Dozens of similar images from other Pages are not labeled, showing the difficulty of scaling fact-checking of AI-generated images if treated individually.

Methods

We surfaced Facebook Pages producing large volumes of unlabeled AI-generated images by 1) searching for ‘copypasta’ captions (captions that are copy-and-pasted across posts), 2) identifying signs of coordination of those Pages with others, 3) looking at Pages that Facebook Users had called out for posting unlabeled AI-generated images, and 4) surfacing new leads from our own Facebook Feed recommendations. We made determinations about whether Pages were using AI-generated images by finding errors in images and periods of highly similar image creation that bore the aesthetic hallmarks of popular image generators. We describe our specific processes below.

First, we noticed Pages posting unlabeled AI-generated images often used overlapping themes with heavy repetition in captions. Searching phrases from the captions in CrowdTangle surfaced other Pages that had posted the same content or highly similar captions.

Once we surfaced a Page, we had to make a determination about whether content was AI-generated. To make this assessment, we relied on obvious mistakes or unrealistic images as well as on analyzing trends in posts. In Figure 11, we show images posted by the Page “Amazing Statues” with three hands (left), hands melded together (middle), and gloves with more than five fingers (right).

We also analyzed patterns in posts: If a Page used a single AI-generated image it did not qualify, but if it posted a large number of photos (50+) that shared a house style (e.g., of Midjourney) we included it in our analysis. Just as Picasso had his Blue Period, the Pages would often go through periods: a few dozen snow carvings, a few dozen watermelon carvings, a few dozen wood carvings, a few dozen plates of artistically arranged sushi—each with a highly similar style. In Figure 12, we provide a screenshot of one such Page moving through different periods.

Second, once we had identified a Page for inclusion, we investigated adjacent Pages. For example, we looked at Pages sharing each other’s content, co-owners of Groups, and Pages suggested by Facebook when viewing another. Third, we noticed Facebook groups of users interested in finding AI-generated images on the platform. These groups often rely on common open-source intelligence techniques, and they provided several leads for our investigation. Fourth, after several days of engaging with material obtained through these searches, we began to observe unlabeled AI-generated images recommended to us on our own Feeds. Searches that returned a high volume of AI-generated images across many different themes—AI-generated homes, rooms, furniture, clothing, animals, babies, people, food, and artwork—resulted in the subsequent algorithmic suggestion of other AI-generated images across additional random themes.

Limitations

Although manual detection methods were sufficient for identifying Pages described above, our identification method has clear limitations regarding representativeness and exhaustiveness. We discovered Pages that formed clusters, relied on copypasta captions, or were recommended in our Feeds. We only included Pages that posted more than 50 AI-generated images. Since we used manual detection methods for identification, our study over-includes Pages that did not take great precautions to weed out erroneous AI-generated images or intersperse them sufficiently with real images. It under-includes Pages that used AI-generated images sparingly (< 50) or did a better job curating for AI output that appears photorealistic.

Our methods also create a lack of representativeness vis-à-vis language and social media platforms. The images we discovered overwhelmingly included English-language captions. This is likely a product of the researchers’ language and region. Additional research should examine (rather than assume) whether and how these findings generalize to non-English speaking audiences on Facebook. Our methods are sufficient for documenting an understudied type of misuse (and is characteristic of online investigations), but the Pages we studied are not necessarily reflective of how unlabeled AI-generated images are used on Facebook as a whole. Additional academic studies should continue to investigate AI-generated content in different modalities (e.g., text, images, and video) on Facebook as well as on other social media platforms where usage may differ.

Finally, our methods provide limited insight into Page operator motivations. Since we do not operate the Pages ourselves nor did we interview Page operators, we cannot be sure of their aims. In some cases, their aims seemed obvious (e.g., when they posted links to the same off-platform website on many posts). At other times, the posting pattern seemed designed with the proximate goal of audience growth but an unknown ultimate goal. We encourage future research on the motivations of Page operators sharing AI-generated content, user expectations around synthetic media, and longitudinal investigations examining how those evolve.

Topics

Bibliography

Bickert, M. (2024, April 5). Our approach to labeling AI-generated content and manipulated media. Meta Newsroom. https://about.fb.com/news/2024/04/metas-approach-to-labeling-ai-generated-content-and-manipulated-media/

Caufield, M. (2019, June 19). SIFT (the four moves). Hapgood. https://hapgood.us/2019/06/19/sift-the-four-moves/

Clegg, N. (2024, February 6). Labeling AI-generated images on Facebook, Instagram and Threads. Meta Newsroom. https://about.fb.com/news/2024/02/labeling-ai-generated-images-on-facebook-instagram-and-threads/

Dixon, R. B. L., & Frase, H. (2024, March). An argument for hybrid AI incident reporting: Lessons learned from other incident reporting systems. Center for Security and Emerging Technology. https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/an-argument-for-hybrid-ai-incident-reporting/

Ferrara, E. (2024). GenAI against humanity: Nefarious applications of generative artificial intelligence and large language models. Journal of Computational Science, 7, 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-024-00250-1

Goldstein, J. A., Chao, J., Grossman, S., Stamos, A., & Tomz, M. (2024, February 20). How persuasive is AI-generated propaganda? PNAS Nexus, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae034

Goldstein, J. A., & DiResta, R. (2022, September 15). This salesperson does not exist: How tactics from political influence operations on social media are deployed for commercial lead generation. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 3(5). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-104

Grbic, D. V., & Dujlovic, I. (2023). Social engineering with ChatGPT. In 2023 22nd International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH), East Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (pp. 1–5). IEEE. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10094141

Heath, A. (2022, June 15). Facebook is changing its algorithm to take on TikTok, leaked memo reveals. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2022/6/15/23168887/facebook-discovery-engine-redesign-tiktok

Hughes, H. C., & Waismel-Manor, I. (2021). The Macedonian fake news industry and the 2016 US election. PS: Political Science & Politics, 54(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000992

Jakesch, M., French, M., Ma, X., Hanckock, J., & Naaman, M. (2019, May 2). AI-mediated communication: How the perception that profile text was written by AI affects trustworthiness. In CHI ’19: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13). Association for Computing Machinery. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3290605.3300469

Koebler, J. (2023, December). Facebook is being overrun with stolen, AI-generated images that people think are real. 404 Media. https://www.404media.co/facebook-is-being-overrun-with-stolen-ai-generated-images-that-people-think-are-real/

Koebler, J. (2024a, January 8). ‘Dogs will pass away’: Hackers steal dog rescue’s Facebook page, turn it into AI content farm. 404 Media. https://www.404media.co/dogs-will-pass-away-hackers-steal-dog-rescues-facebook-page-turn-it-into-ai-content-farm/

Koebler, J. (2024b, March 5). Inside the world of TikTok spammers and the AI tools that enable them. 404 Media. https://www.404media.co/inside-the-world-of-tiktok-spammers-and-the-ai-tools-that-enable-them/

Koebler, J. (2024c, March 19). Facebook’s algorithm is boosting AI spam that links to AI-generated ad laden click farms. 404 Media. https://www.404media.co/facebooks-algorithm-is-boosting-ai-spam-that-links-to-ai-generated-ad-laden-click-farms/

Limbong, A. (2024, March 13). Authors push back on the growing number of AI ‘scam’ books on Amazon. NPR Morning Edition. https://www.npr.org/2024/03/13/1237888126/growing-number-ai-scam-books-amazon

Metaxas, P. T., & DeStefano, K. (2005). Web spam, propaganda and trust. In AIRWeb: First international workshop on adversarial information retrieval on the web (pp. 70–78). Association for Computing Machinery. https://airweb.cse.lehigh.edu/2005/metaxas.pdf

Mouton, C., Lucas, C., & Guest, E. (2024). The operational risks of AI in large-scale biological attacks. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2977-2.html

Munich Security Conference. (2024, February). A tech accord to combat deceptive use of AI in 2024 elections. https://securityconference.org/en/aielectionsaccord/accord/

Phua, J. & Ahn, S. J. (2016). Explicating the ‘like’ on Facebook brand pages: The effect of intensity of Facebook use, number of overall ‘likes’, and number of friends’ ‘likes’ on consumers’ brand outcomes. Journal of Marketing Communications, 22(5), 544–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2014.941000

Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., Goldberg, B., Rathje, S., & Lewandowsky, S. (2022). Psychological inoculation improves resilience against misinformation on social media. Science Advances, 8(34). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo6254

Seger, E., Avin, S., Pearson, G., Briers, M., Heigeartaigh, S. Ó., Bacon, H. (2020). Tackling threats to informed decision-making in democratic societies: Promoting epistemic security in a technologically-advanced world. The Alan Turing Institute. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.64183

Spitale, G., Biller-Andorno, N., & Germani, F. (2023). AI model GPT-3 (dis) informs us better than humans. Science Advances, 9(26). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adh1850

Subramanian, S. (2017, February 15). The Macedonian teens who mastered fake news. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2017/02/veles-macedonia-fake-news/

Walker, C. P., Schiff, D. S., Schiff, K. J. (2024). Merging AI incidents research with political misinformation research: Introducing the political deepfakes incidents database. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 38(21), 23503-8. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v38i21.30349

Watukalusu, H. (2024, January 28). Engagement-bait: Une photo générée par l’I.A faussement légendée incitant les internautes à commenter [Engagement-bait: A falsely captioned A.I. photo prompts internet users to comment]. Congo Check. https://congocheck.net/engagement-bait-une-photo-generee-par-li-a-faussement-legendee-incitant-les-internautes-a-commenter/?fbclid=IwAR2oGPAh63Sm8_CGRa3yqOL1g81kK7qdsP1yaprIhtNtZR0avwYvDp9ZApc

Weidinger, L., Uesato, J., Rauh, M., Griffin, C., Huang, P. S., Mellor, J., Glaese, A., Cheng, M., Balle, B., Kasirzadeh, A., Biles, C., Brown, S., Kenton, Z., Hawkins, W., Stepleton, T., Birhane, A., Hendricks, L. A., Rimell, L., Isaac, W., … Gabriel, I. (2022). Taxonomy of risks posed by language models. In FACCT ’22: Proceedings of the 2022 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency (pp. 214–229). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3531146.3533088

Yang, A. (2024). Facebook users say ‘amen’ to bizarre AI-generated images of Jesus. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-users-say-amen-bizarre-ai-generated-images-jesus-rcna143965

Yang, K. C., Singh, D., & Menczer, F. (2024). Characteristics and prevalence of fake social media profiles with AI-generated faces. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.02627

Funding

No funding has been received to conduct this research.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

We relied exclusively on publicly available data and did not seek IRB approval.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

CrowdTangle prohibits users from publishing datasets of posts in full. We, therefore, included screenshots in the paper but cannot provide a full dataset of posts and engagements from the Pages.

Acknowledgements

We thank Abhiram Reddy for excellent research assistance. For feedback on our investigation or an earlier draft of this paper, we thank Elena Cryst, Shelby Grossman, Jeff Hancock, Justin Hileman, Ronald Robertson, David Thiel, and two anonymous reviewers.

Authorship

Authors contributed equally to this research.