Peer Reviewed

Developing an accuracy-prompt toolkit to reduce COVID-19 misinformation online

Article Metrics

38

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Recent research suggests that shifting users’ attention to accuracy increases the quality of news they subsequently share online. Here we help develop this initial observation into a suite of deployable interventions for practitioners. We ask (i) how prior results generalize to other approaches for prompting users to consider accuracy, and (ii) for whom these prompts are more versus less effective. In a large survey experiment examining participants’ intentions to share true and false headlines about COVID-19, we identify a variety of different accuracy prompts that successfully increase sharing discernment across a wide range of demographic subgroups while maintaining user autonomy.

Research Questions

There is mounting evidence that inattention to accuracy plays an important role in the spread of misinformation online. Here we examine the utility of a suite of different accuracy prompts aimed at increasing the quality of news shared by social media users.

- Which approaches to shifting attention towards accuracy are most effective?

- Does the effectiveness of the accuracy prompts vary based on social media user characteristics? Assessing effectiveness across subgroups is practically important for examining the generalizability of the treatments and is theoretically important for exploring the underlying mechanism.

Essay Summary

- Using survey experiments with N = 9,070 American social media users (quota-matched to the national distribution on age, gender, ethnicity, and geographic region), we compared the effect of different treatments designed to induce people to think about accuracy when deciding what news to share. Participants received one of the treatments (or were assigned to a control condition), and then indicated how likely they would be to share a series of true and false news posts about COVID-19.

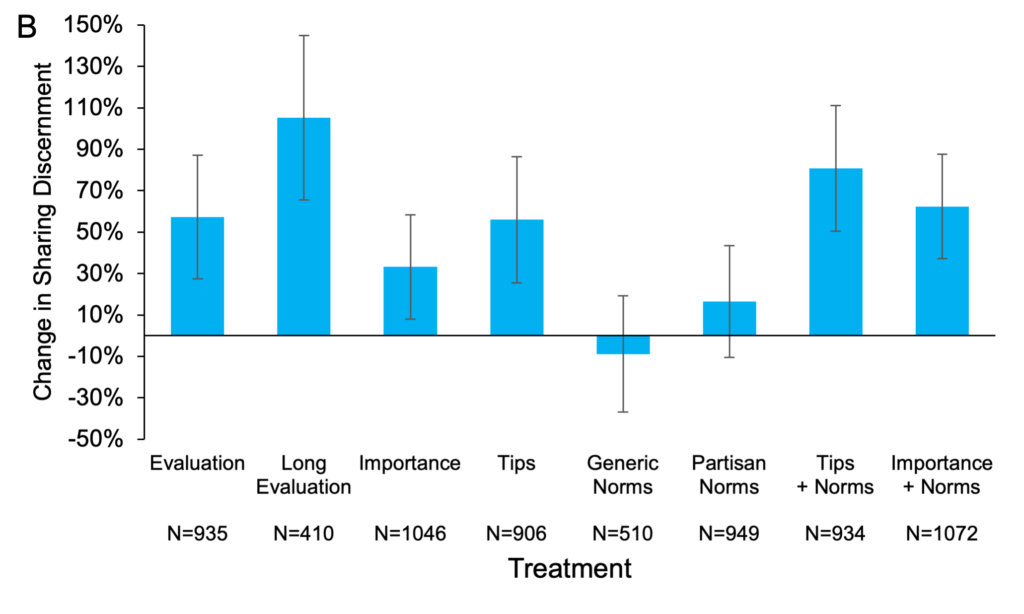

- We identified three lightweight, easily-implementable approaches that each increased sharing discernment (the quality of news shared, measured as the difference in sharing probability of true versus false headlines) by roughly 50%, and a slightly more lengthy approach that increased sharing discernment by close to 100%. We also found that another approach that seemed promising ex ante (descriptive norms) was ineffective. Furthermore, we found that gender, race, partisanship, and concern about COVID-19 did not moderate effectiveness, suggesting that the accuracy prompts will be effective for a wide range of demographic subgroups. Finally, helping to illuminate the mechanism behind the effect, the prompts were more effective for participants who were more attentive, reflective, engaged with COVID-related news, concerned about accuracy, college-educated, and middle-aged.

- From a practical perspective, our results suggest a menu of accuracy prompts that are effective in our experimental setting and that technology companies could consider testing on their own services.

Implications

The spread of inaccuracies on social media — including political “fake news” (Lazer et al., 2018; Pennycook & Rand, 2021) and COVID-19 misinformation (Pennycook, McPhetres et al., 2020) — is a topic of great societal concern and focus of academic research. Of particular importance is identifying approaches that technology companies could directly use to combat online misinformation. Here we focus on reducing the sharing of misinformation because simply being exposed to misinformation can increase subsequent belief (Pennycook et al., 2018). Thus, it is especially important to prevent initial exposure. To that end, we explore the effectiveness of shifting users’ attention toward accuracy. Recent work suggests that misinformation sharing often occurs, not because people purposefully share news they know is inaccurate, but because people are distracted or focused on other elements when deciding what to share. As a result, shifting attention towards accuracy can help people attend to their existing — but often latent — capacity and desire to discern truth from falsehood, for both political misinformation (Fazio, 2020; Jahanbakhsh et al., 2021; Pennycook et al., 2021) and COVID-19 misinformation (Pennycook, McPhetres et al., 2020). This approach is particularly appealing because it does not require technology companies to decide (e.g., via machine learning or human moderators) what is true versus false. Rather, emphasizing accuracy helps users exercise the (widely held; see Pennycook et al., 2021) desire to avoid sharing inaccurate content, preserving user autonomy. This approach is also appealing from a practical perspective because accuracy prompts are scalable (unlike, for example, professional fact-checking, which is typically slow and only covers a small fraction of all news content; Pennycook, Bear et al., 2020).

Here, we advance the applicability of accuracy prompt interventions by asking which such interventions are effective. We focused on COVID-19 misinformation, and began by replicating prior findings (Pennycook et al., 2021; Pennycook, McPhetres et al., 2020) that, in the absence of any intervention, headline veracity has little impact on sharing intentions — despite participants being fairly discerning when asked to judge the accuracy of the headlines. That is, there is a substantial disconnect between accuracy judgments and sharing intentions.

We then compared the relative effectiveness of several different ways to induce people to think about accuracy, all delivered immediately prior to the sharing task. We found that (i) asking participants to judge the accuracy of a non-COVID-19 related headline, (ii) providing minimal digital literacy tips, and (iii) asking participants how important it was to them to share only accurate news, all increased sharing discernment by roughly 50% (3 percentage points); and that (iv) asking participants to judge the accuracy of a series of 4 non-COVID-19–related headlines (and providing corrective feedback on their responses) increased sharing discernment by roughly 100% (6 percentage points), all by decreasing the sharing of false but not true headlines. Conversely, (v) informing participants that other people thought it was important to share only accurate news (providing “descriptive norm” information) was ineffective on its own but may have increased the effectiveness of other approaches when implemented together.

From a practical perspective, these findings demonstrate that accuracy prompt effects are not unique to the particular implementations used in prior work and provide platform designers with a menu of effective accuracy prompts to choose from (and ideally cycle through, to reduce adaption and banner blindness) when creating user experiences to increase the quality of information online. Our results also suggest important directions for future research, such as assessing how long the effects last, how quickly users become insensitive to repeated treatment, and how our results would generalize cross-culturally. Additionally, further work is required to test the ecological validity of these interventions across different online services (querying a search engine versus browsing a social media feed, for example) and other content verticals where accuracy might be important.

From a theoretical perspective, we found that the treatments operate by reducing the disconnect between accuracy judgments and sharing intentions observed in the baseline condition: By shifting participants’ attention to accuracy, we increased the link between a headline’s perceived accuracy and its likelihood of being shared. The observation that approaches (i), (ii), and (iii) were equally effective sheds further light on the mechanism driving these effects. In particular, the tips (ii) were no more effective than merely having participants make an accuracy judgment (i), suggesting that the treatments work almost entirely by priming accuracy, rather than via knowledge transmission per se. Explicitly stating a commitment to accuracy (iii) was no more effective than the simple accuracy prime (i), indicating that the mechanism is not commitment per se, either. This is promising from an applied perspective, as it suggests that simply shifting attention to accuracy can be effective in and of itself, and that this can be done in a wide variety of ways.

We also examined whether the effect of these treatments varied based on numerous user characteristics. We found various moderators that support our proposed mechanism. Foremost, the treatment was more effective for participants who were more attentive, consistent with the idea that one must notice the treatments in order to be affected. The effect was also stronger among people who placed greater importance on sharing only accurate news, consistent with the idea that shifting attention to accuracy should increase sharing discernment only insofar as the user actually cares about accuracy (as formalized by a limit-attentioned utility model in Pennycook et al. [2021]). Finally, the effect was stronger among those who engaged in more analytic thinking, self-reported engaging with COVID-related news to a greater extent, and were college-educated, all of which are consistent with the idea that these users seem likely to have a greater knowledge base upon which to draw when evaluating the headlines (or a greater ability to do so); although importantly the treatment still significantly increased sharing discernment among less analytic, less COVID-19-news engaged, and non-college educated participants. These all support our interpretation that our treatment effect, across conditions, is driven by increased attention to accuracy — as does a headline-level analysis finding that the effect of the treatments on sharing of a given headline is strongly correlated with the perceived accuracy of that headline.

Furthermore, we found no evidence that the treatment effect on sharing discernment varied significantly based on gender, race, partisanship, or concern about COVID-19; and although the treatment effect did vary non-linearly with age (such that it was most effective for middle-aged participants), sharing discernment was significantly increased for all age groups (18–34, 35–50, 50–64, 65+). From a practical perspective, these results suggest that accuracy prompts are likely to work for diverse groups of users, even those who may approach sharing in a motivated way (e.g., those who are not concerned about COVID-19 or who may be motivated to downplay COVID risks). This indicates that the intervention is widely applicable.

Together, our results help to inform social media platforms, civil society organizations, and policy makers about how to most effectively prompt users to consider accuracy online. We hope that our work will help guide efforts to reduce the spread of misinformation online.

Findings

A disconnect exists between accuracy judgments and sharing intentions

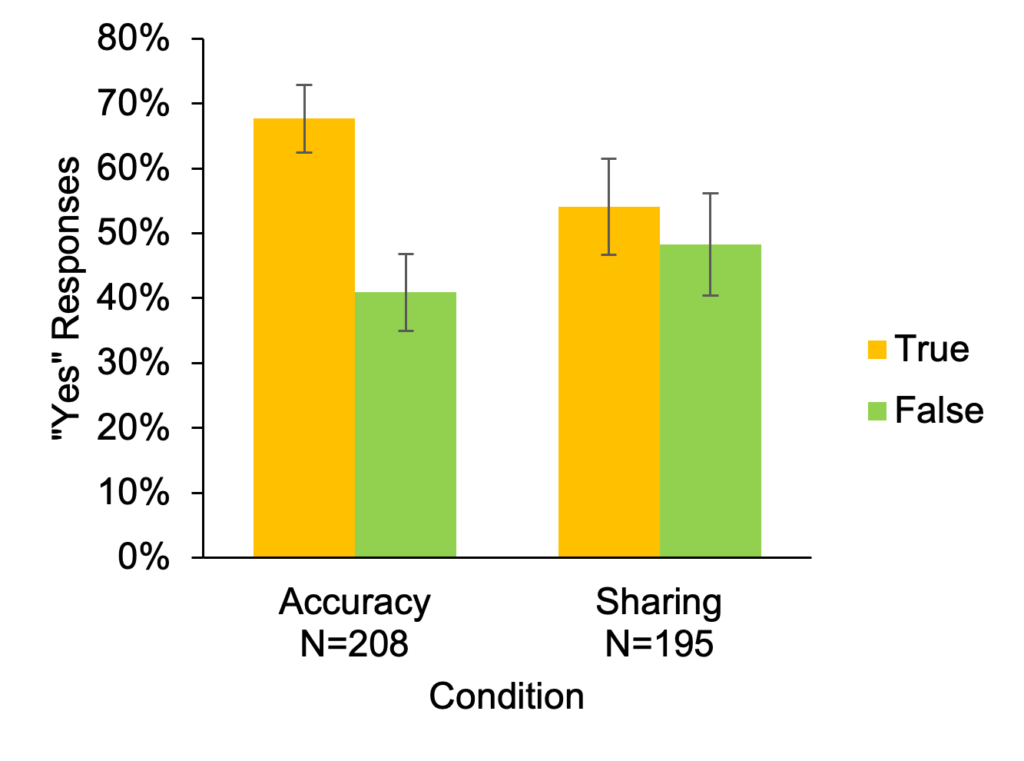

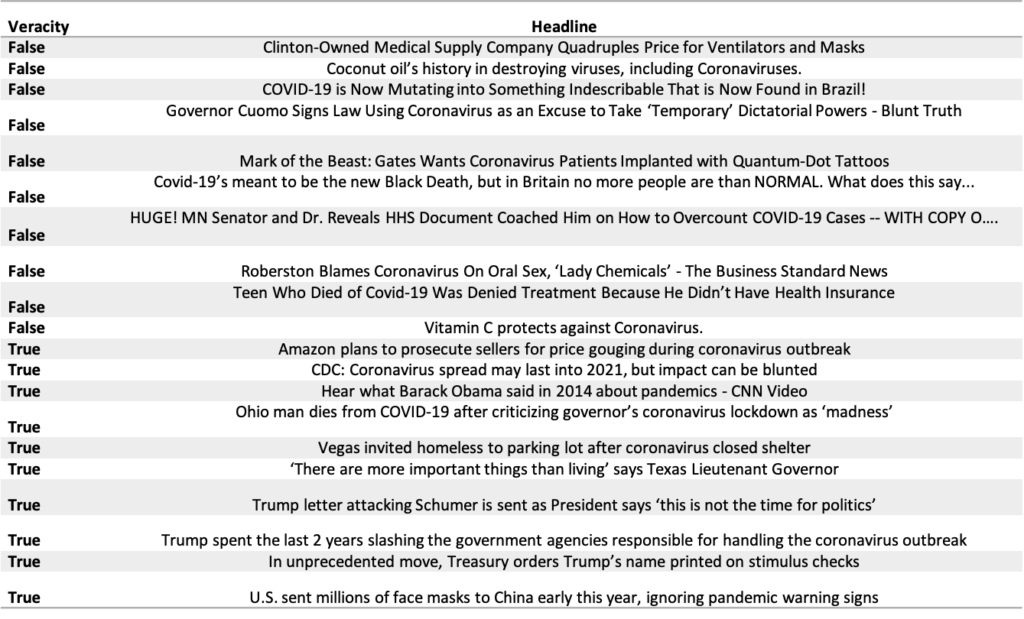

Consistent with past work, we found that sharing intentions were much less discerning than accuracy judgments; see Figure 1. When asked to judge the accuracy of 20 COVID-19 related headlines (half true, half false), participants displayed a fair level of discernment: True headlines were much more likely to be rated as accurate (67.7%) than false headlines (40.9%; p < .0001). When a separate group of participants recruited at the same time were instead asked if they would share the same set of headlines online, the results were strikingly different: Veracity had no significant impact on sharing intentions (True headlines 54.1%, False headlines 48.3%, p = .19; interaction between condition and veracity, p <.0001).

Various accuracy prompts increase sharing discernment

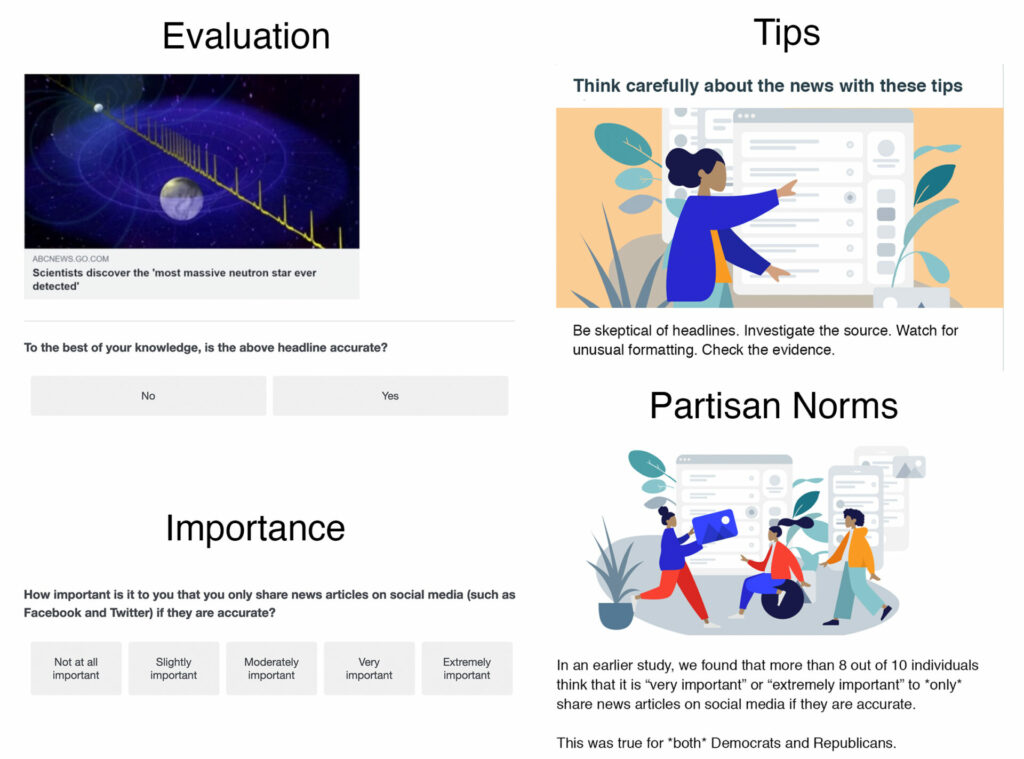

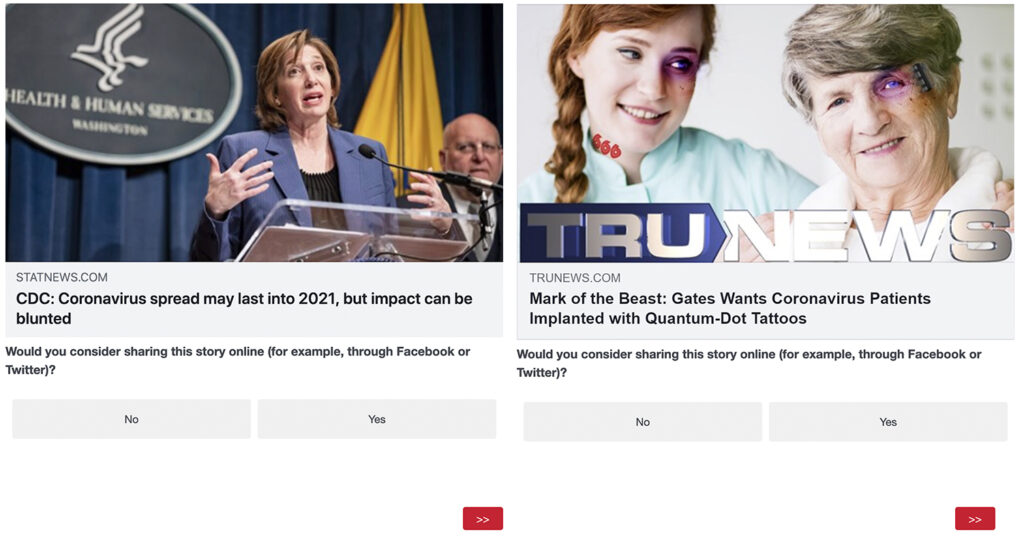

We then assessed the impact of eight different experimental treatments on sharing intentions of true versus false headlines (sample materials are shown in Figure 2). Each treatment was administered prior to the beginning of the news sharing task, as follows:

- In the “Evaluation” treatment, as in Pennycook et al. (2021) and Pennycook, McPhetres et al. (2020), participants were asked to evaluate the accuracy of a single non-COVID-related headline — thereby priming the concept of accuracy when the participants continued on to the sharing task.

- In the “Long Evaluation” treatment, participants evaluated the accuracy of eight non-COVID-related headlines (half true, half false). After each headline, they were (accurately) informed about whether their answer was correct or incorrect and whether the preceding headline was “a real news headline” or “a fake news headline.” No source was provided for the answers we provided to them.

- In the “Importance” treatment, as in Pennycook et al. (2021), participants were asked “How important is it to you that you share only news articles on social media (such as Facebook and Twitter) if they are accurate?”

- In the “Tips” treatment, participants were provided with four simple digital literacy tips, taken from an intervention developed by Facebook (Guess et al., 2020).

- In the “Generic Norms” treatment, participants were informed that over 80% of past survey respondents said it was important to think about accuracy before sharing.

- In the “Partisan Norms” treatment, participants were informed that 8 out of 10 past survey respondents said it was “very important” or “extremely important” to share only accurate news online, and that this was true of both Democrats and Republicans.

- In the “Tips+Norms” treatment, participants were shown both the “Partisan Norms” treatment and the “Tips” treatment, in that order.

- In the “Importance+Norms” treatment, participants were shown both the “Importance” treatment and the “Partisan Norms” treatment, in random order.

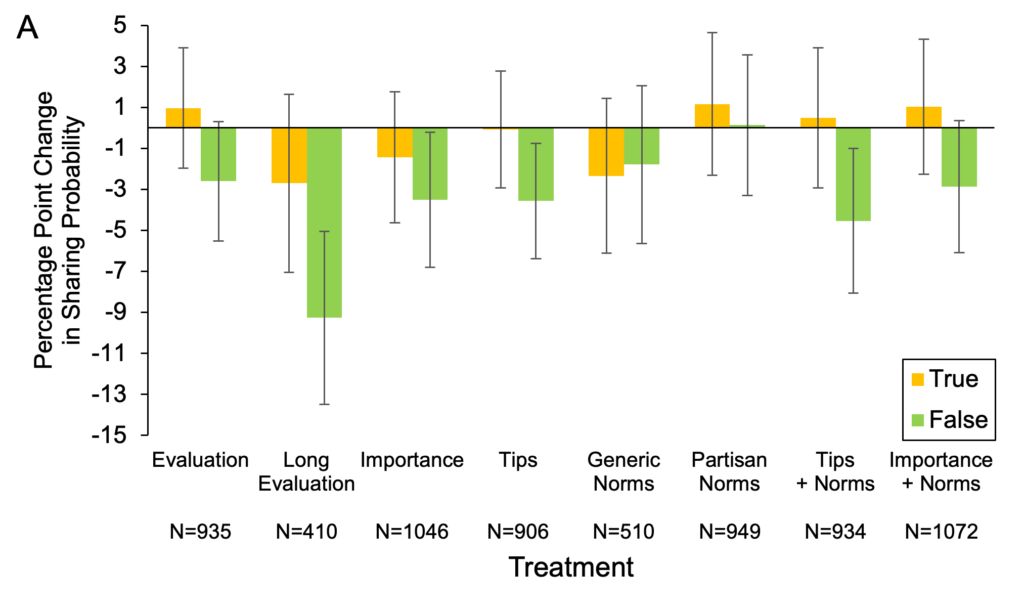

For each treatment, the percentage point change relative to the control in sharing of true and false headlines is shown in Figure 3(A), and the percent change relative to the control in sharing discernment is shown in Figure 3(B). As can be seen, the Evaluation, Tips, and Importance treatments significantly increased sharing discernment (p < 0.001 for all except p = 0.010 for Importance), whereas the two norms-only treatments did not significantly affect sharing discernment (p = 0.54 for Generic Norms, p = 0.22 for Partisan Norms). The increase in sharing discernment for the effective treatments was largely driven by a decrease in the probability of sharing false news (p < 0.05 for all, except for Evaluation at p = 0.075 and Importance+Norms at p = 0.081; aggregating all treatments, p < 0.001), rather than a change in the probability of sharing true news (p > 0.22 for all). The effective treatments led to significantly larger increases in sharing discernment than the (ineffective) norms treatments (p < 0.05 for all comparisons, except for Importance versus Partisan Norms, p = 0.31). Among the effective treatments, Long Evaluation was significantly more effective than most of the other treatments (p < 0.05 for all except for Long Evaluation versus Tips+Norms at p = 0.152), while there were few significant differences between the other effective treatments (p > 0.05 for all, except for Importance being significantly less effective than Tips+Norms, p = 0.002 and Importance+Norms, p = 0.046).

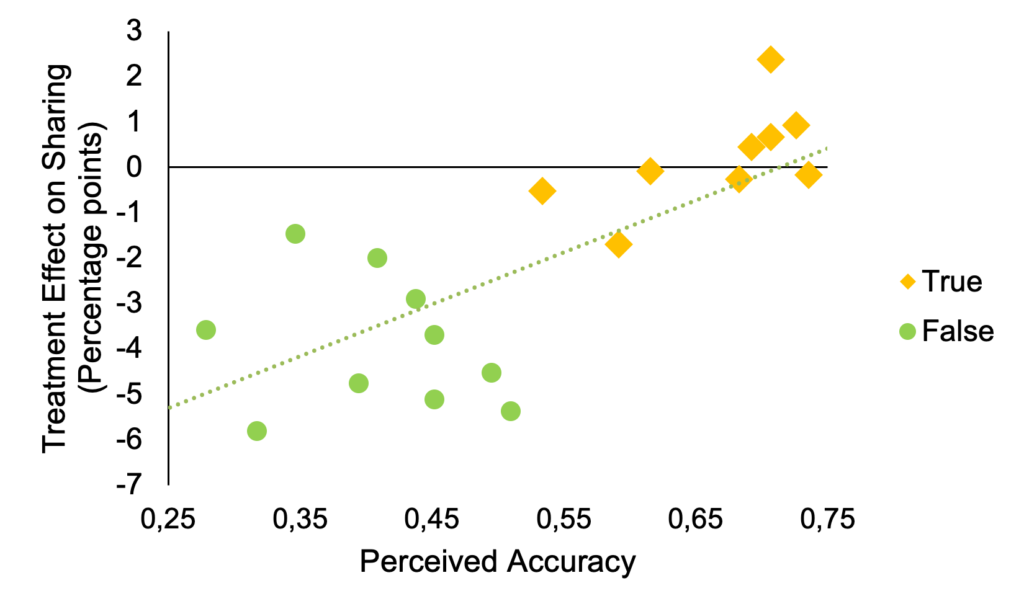

The treatments operate by narrowing the gap between accuracy perceptions and sharing intentions

Next, we examined the mechanism underlying the observed treatment effect. To do so, we conducted a headline-level analysis. For each headline, we calculated its perceived accuracy (breaking down the accuracy data in Figure 1 by headline) and the overall impact of the effective treatments on sharing intentions for that headline (average sharing intention among participants in any of the effective treatments minus average sharing intention among control participants; excludes participants in the two norms treatments). As shown in Figure 4, we find a strong positive correlation (r(18) = 0.742, p < 0.001), such that the more inaccurate a headline seemed to participants, the more its sharing was decreased by the treatments. In other words, the disconnect between perceived accuracy and sharing intentions was smaller in the treatments than in the control.

Does the treatment effect size vary based on user characteristics?

By looking at the three-way interaction between headline veracity, treatment, and various covariates of interest, we can assess heterogeneous treatment effects based on each covariate. Because higher order interactions require substantially more statistical power (i.e., larger sample size) to detect, we do not investigate differences between treatments, but instead compare the control to have received any of the effective treatments (and exclude the two norms treatments) for this analysis. Because these analyses are exploratory and involve a substantial number of tests, we adjust for the possibility of false positives that arises from conducting multiple comparisons by applying the Holm–Bonferroni correction to the reported p-values (Holm, 1979).

We find significant positive 3-way interactions between veracity, treatment, and the following variables (such that each variable is associated with a larger treatment effect): the number of attention checks passed by the participant (pholm < 0.001), self-reported importance placed on sharing only accurate content (pholm = 0.039), self-reported tendency to seek out news about COVID-19 (pholm = 0.008), the tendency to stop and think rather than going with one’s intuitive first responses (pholm = 0.007) as measured behaviorally using the Cognitive Reflection Test (a series of questions with intuitively compelling but wrong answers), education (college degree or higher, pholm = 0.026), and age (pholm = 0.045, joint significance test of linear and quadratic terms).

Conversely, we find no significant moderation based on participants’ preference for the Republican versus Democratic party (pholm = 0.746), concern about COVID-19 (pholm= 0.555), race (pholm = 0.179), or gender (pholm = 0.895).

Methods

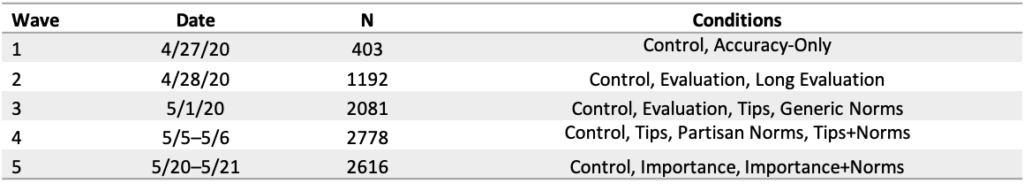

From April 27 to May 21, 2020, we conducted five waves of data collection. A total of 11,237 participants began the study, of which 9,070 participants completed the survey (and thus constitute our final sample); mage = 44.5; 44.9% male, 54.2% female, 0.9% other; 72.4% White/Caucasian.

Participants were recruited using Lucid, an aggregator of survey platforms that provides samples that are quota matched to the U.S. on age, gender, race, and geographic region. In all waves, participants were shown 20 online news cards (e.g., the combination of a headline, an image, and a source) pertaining to COVID-19. Half were true and half were false. For a list of the headlines used, see Table 2; full experimental materials are available at https://osf.io/hu4k2/. In all conditions except for the Accuracy-Only condition, participants were asked “Would you consider sharing this story online (for example, through Facebook or Twitter)?” (No/Yes binary response); in the Accuracy-Only condition, they were asked “To the best of your knowledge, is the claim in the above headline accurate?” The sharing intentions input screen for a sample true and false headline are shown in Figure 4. Although we measure sharing intentions rather than actual sharing, some evidence in support of the validity of this self-report measure comes from the observation that news headlines that Mechanical Turk participants report a higher likelihood of sharing indeed received more shares on Twitter (Mosleh et al., 2020); as well as the observation that accuracy prompts increase sharing discernment for political headlines using both self-report sharing intentions and actual sharing in a Twitter field experiment (Pennycook et al., 2021).

As described in detail above, in addition to the Accuracy-Only condition and a control condition, we ran 8 treatments that consisted of short accuracy prompts administered immediately prior to the sharing task (see Table 1 for a list of which treatments were included in each wave of data collection).

Prior to the main task, participants indicated their level of concern about COVID-19 and the extent to which they had been following COVID-19–related news. Following the main task, participants completed the Cognitive Reflection Test (Frederick, 2005), the question about the importance of sharing only accurate news (except for participants in the Importance treatment, who completed this question at the study outset), and demographics. We measured ethnicity with the following labels (White/Caucasian, Asian, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, other), and gender with the following labels (Male, Female, Transgender Male, Transgender Female, Trans/non-binary, not listed, prefer not to answer). Ethnicity and gender are important to consider for this study to check that the intervention works for a diverse set of participants.

All p-values are calculated using linear regression where the dependent variable is the participant’s choice (share/don’t share for all conditions except for the Accuracy-Only condition where the choice was true/false), with two-way standard errors clustered on participant and headline to account for the non-independence of repeated choices from the subject, and repeated choices for the same headline. The independent variables were an indicator variable for headline veracity (0 = false, 1 = true), indicator variables for each treatment, and interactions between veracity and each treatment indicator (capturing the effect of each treatment on sharing discernment), as well as indicators for wave (to account for variation across waves in baseline sharing rates). For the two treatments that were administered in multiple waves (Evaluation and Tips), we included separate indicator variables for each treatment-wave combination and used an average of the two coefficients weighted by the treatment sample size in each wave (using bootstrapping to calculate confidence intervals for plotting). For the moderation analyses, we used a single “treated” indicator (0 = control, 1 = any of the effective treatments), and interacted the veracity indicator, the treated indicator, and the veracity X treated interaction with the covariate of interest.

Topics

Bibliography

Fazio, L. (2020). Pausing to consider why a headline is true or false can help reduce the sharing of false news. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-009

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533005775196732

Guess, A. M., Lerner, M., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., & Neelanjan, S. (2020). A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and False News in the United States and India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(27), 15536–15545. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920498117

Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6(2), 65–70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4615733?origin=JSTOR-pdf

Jahanbakhsh, F., Zhang, A. X., Berinsky, A. J., Pennycook, G., Rand, D. G., & Karger, D. R. (2021). Exploring lightweight interventions at posting time to reduce the sharing of misinformation on social media. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5 (CSCW1). https://doi.org/10.1145/3449092

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F. Metzger, M., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

Mosleh, M., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Self-reported willingness to share political news articles in online surveys correlates with actual sharing on Twitter. PLOS ONE, 15(2), e0228882. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228882

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(5), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007

Pennycook, G., Bear, A., Collins, E. T., & Rand, D. G. (2020). The implied truth effect: Attaching warnings to a subset of fake news headlines increases perceived accuracy of headlines without warnings. Management Science, 66(11), 4944–4957. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2019.3478

Pennycook, G., Cannon, T. D., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(12), 1865–1880. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000465

Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A. A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature, 592, 590–595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03344-2

Pennycook, G., McPhetres, J., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychological Science, 31(7), 770–780. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0956797620939054

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Initiative of the Miami Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Reset Initiative of Luminate (part of the Omidyar Network), the John Templeton Foundation, the TDF Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and Google.

Competing Interests

AB and DR received research support through gifts from Google; RC and AG work for Google.

Ethics

This research was deemed exempt by the MIT Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects, #1806400195.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/18SHLJ