Peer Reviewed

The role of narrative in misinformation games

Article Metrics

2

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Several existing media literacy games aim to increase resilience to misinformation. However, they lack variety in their approaches. The vast majority focus on assessing information accuracy, with limited exploration of socio-emotional influences of misinformation adoption. Misinformation correction and educational games have explored how narrative persuasion influences personal beliefs, as identification with certain narratives can frame the interpretation of information. We created a preliminary framework for designers seeking to develop narrative-driven misinformation games that synthesizes findings from psychology, narrative theory, and game design. In addition, we conducted a narrative-centered content analysis of existing media literacy games.

Research Questions

- How can the narratives of existing misinformation games help address psychological drivers of misinformation?

- What aspects of narrative design are important to consider in the context of games for misinformation education?

Essay Summary

- We compiled findings from misinformation psychology, game studies, and narrative theory to inform a content analysis of how existing misinformation education games are utilizing narrative to address psychological drivers of misinformation.

- Researchers across the fields of misinformation, educational games, and communication theory have used narrative to 1) promote identification with opposing viewpoints, 2) reduce counterarguing and reactance, and 3) facilitate connection to educational outcomes.

- We summarize our findings into the misinformation game narrative design (MGND) framework, which can be used by researchers and designers to create game-based misinformation interventions targeted at specific audiences.

Implications

Misinformation and disinformation have many widespread and often harmful effects on society due to their ability to shape people’s beliefs and behaviors (Ecker et al., 2022). This has led to calls to feature misinformation more predominantly in mainstream media literacy curricula (Dame Adjin-Tettey, 2022). Media literacy was shown to positively correlate with correct determination of the accuracy of online information (Kahne & Bowyer, 2017).

Games have been suggested as a promising educational medium for effective media literacy interventions (Chang et al., 2020). The immersive nature of games allows players to creatively engage with real-world situations as thought experiments (Schulzke, 2014), allowing for a safe space to investigate complex issues. Indeed, researchers and educators have created games that aim to improve media literacy (Contreras-Espinosa & Eguia-Gomez, 2023; Kiili et al., 2023) and effectively inoculate players from misinformation and disinformation (Basol et al., 2020; Maertens et al., 2021; Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019; van der Linden et al., 2017). However, there are limitations to the existing body of game-based misinformation interventions, namely their lack of theoretical variance. The majority are based in inoculation theory (Kiili et al., 2023), and recent work has suggested that inoculation-based interventions may simply increase the likelihood of conservative reporting, rather than critical engagement with misinformation (Modirrousta-Galian & Higham, 2023). While informative, these interventions primarily address rational processes of misinformation correction (i.e., teaching basic media literacy competencies). However, the processing and subsequent adoption of misinformation is also heavily influenced by psychological drivers and personal belief (Ecker et al., 2022). Thus, it is essential for designers of misinformation education games to facilitate player exploration of the socio-emotional influences that can lead to the acceptance and spread of misinformation.

Research on misinformation correction and educational games has explored a common method to engage with people on an emotional basis: narrative (Cohen et al., 2015; Domínguez et al., 2016; Iten et al., 2018; Mahood & Hanus, 2017; Ophir et al., 2020; Sangalang et al., 2019). We define narrative as a story that contains event(s), character(s), setting(s), structure, a clear point of view, and a sense of time (Chatman, 1978). Reading, processing, and identifying with narratives is a fundamental component of how we organize our interpretations of reality (Bruner, 1990). However, despite the effectiveness of narrative persuasion in both misinformation correction (Cohen et al., 2015; Ophir et al., 2020; Sangalang et al., 2019) and educational games (Domínguez et al., 2016; Iten et al., 2018; Mahood & Hanus, 2017), current misinformation games are notably lacking in narrative-driven learning mechanisms, as their primary focus tends to be on improving skill-based or knowledge-based information literacy (Contreras-Espinosa & Eguia-Gomez, 2023). There is a strong potential for using narrative as a tool for prompting player empathy and emotional connection within misinformation education (Grace & Liang, 2024).

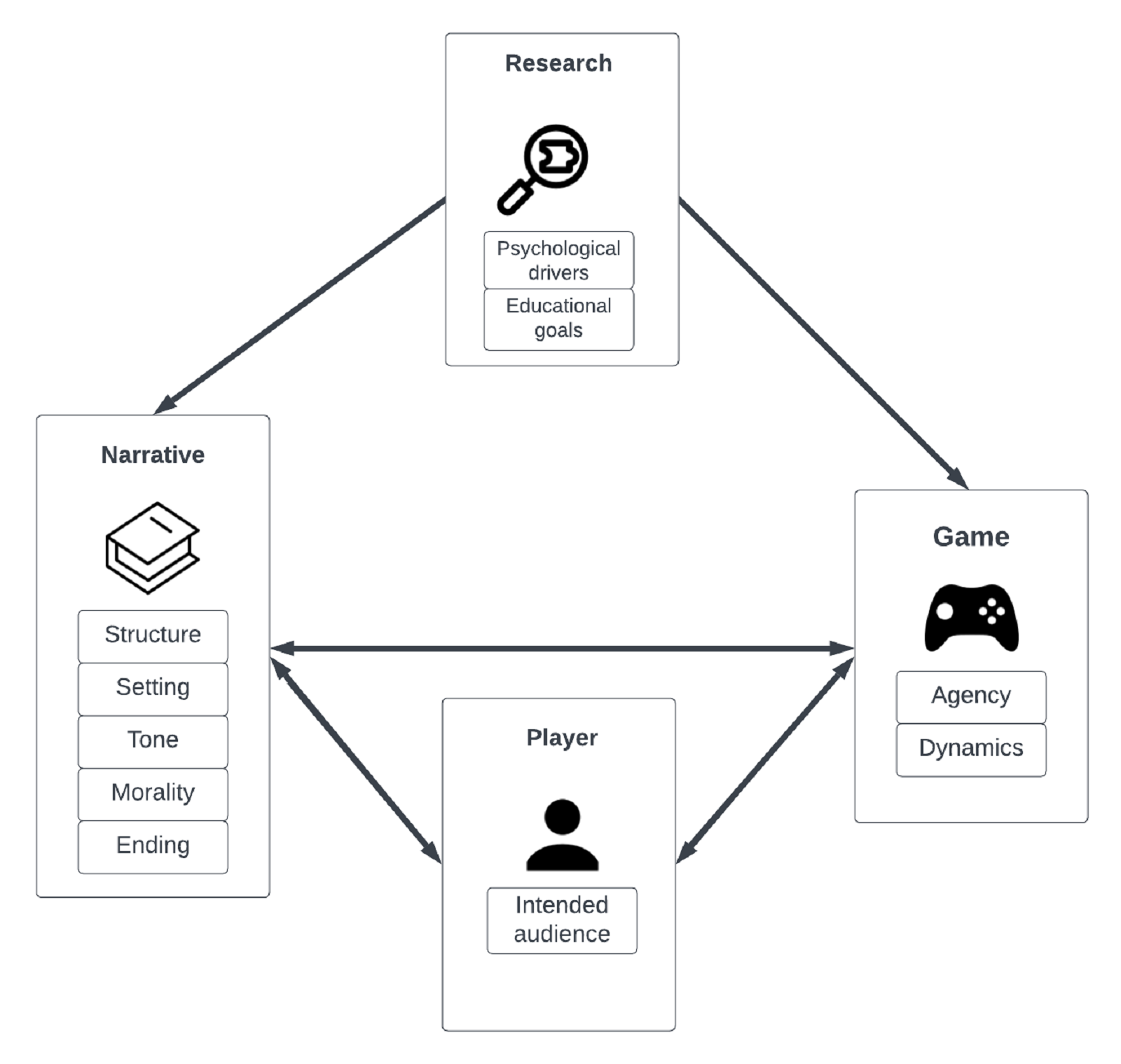

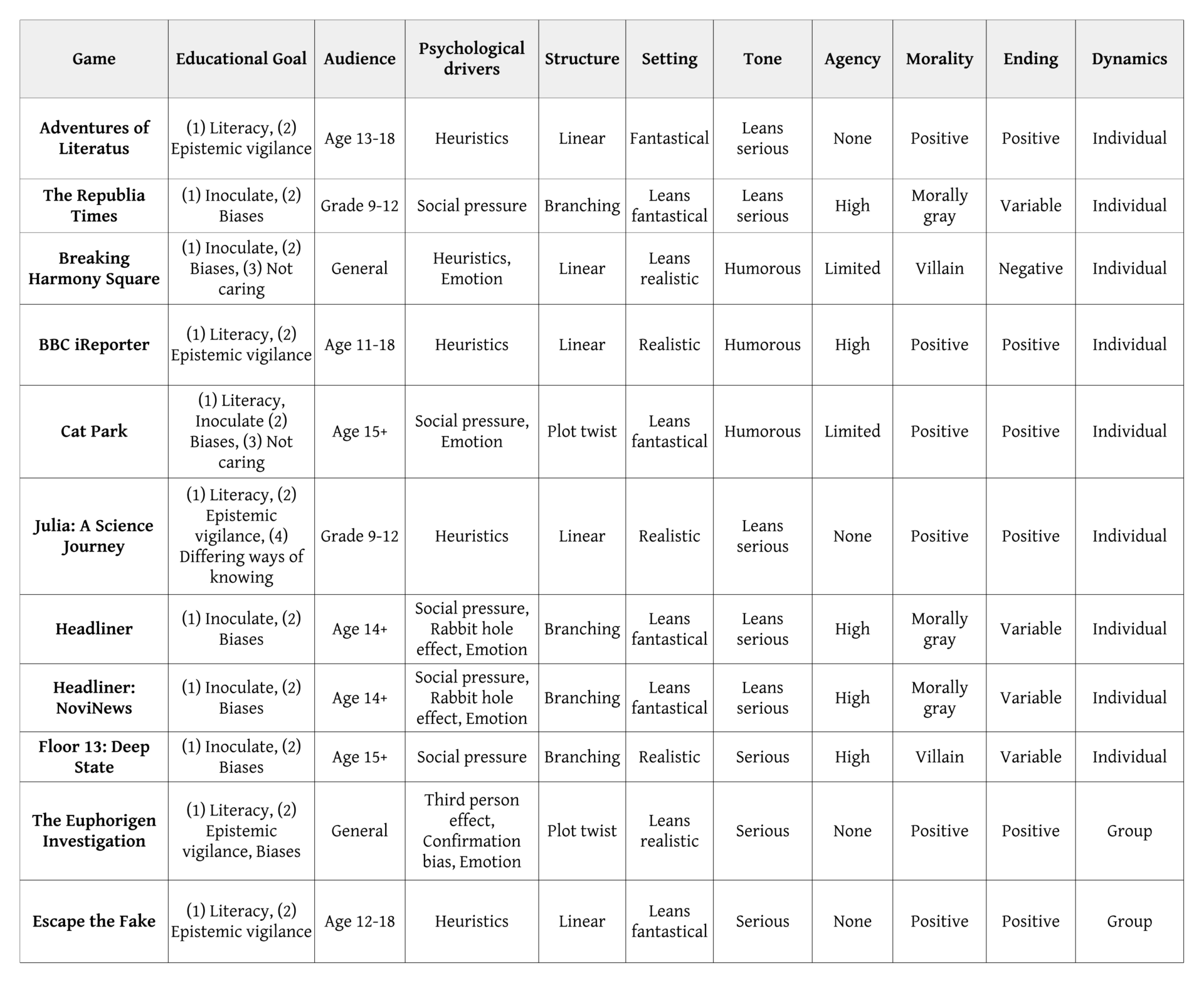

Misinformation game narrative design (MGND) framework

We synthesized possible benefits of narrative-based education games from communication theory and game design and developed an understanding of how key narrative elements, such as those presented in Chatman (1978), may synergize with game mechanics to emotionally connect with players. Using these learnings as a basis, we then performed a content analysis of current misinformation education games. We used our findings to map an initial framework for designers seeking to create narrative-driven misinformation games. We intend to aid these designers, as well as educators and practitioners, in tying certain narrative elements to their intended learning outcomes. Our proposed design framework, the misinformation game narrative design (MGND) framework, consists of ten dimensions, each of which contains several elements. We began by choosing relevant dimensions (i.e., structure, setting, and characters) from Chatman’s definition of narrative (1978). We then integrated game design elements, such as player agency and dynamics, as well as considerations from misinformation psychology, namely the psychological drivers and the correction type the designer is creating. The intended audience must also be centered through the design. It is possible for a game narrative to have multiple elements within each dimension or exist on a sliding scale between two elements. The dimensions are as follows: educational goals, intended audience, psychological drivers, narrative structure, setting, tone, player agency, player morality, ending, and player dynamics.

Educational goals: What arethe intended educational goals? We derived the following goals from Barzilai and Chinn’s (2020) educational lenses for a post-truth world:

- Addressing not knowing how to know. Learners may have gaps in their knowledge and skills for critically dealing with misinformation in digital spheres. Educational games can remedy this by promoting civic, digital, and scientific literacy, as well as inoculating against misinformation.

- Addressing fallible ways of knowing. Adoption of misinformation is strongly influenced by cognitive biases. Educational games can mitigate this by teaching players about cognitive and socioemotional biases and cultivating epistemic vigilance through evaluating the reliability and trustworthiness of information.

- Addressing not caring enough about truth. Misinformation is often propagated by actors who do not necessarily care that they are being misleading or if they are being misled. Educational games can address this by teaching players about the potential consequences of not taking misleading information seriously.

- Addressing disagreeing about how to know. People have ways of seeing the world that are often in conflict with each other. Educational games should emphasize authoritative sources and incorporate debunking strategies when necessary. At the same time, they should teach players how to discuss and evaluate differing beliefs while recognizing and coordinating various epistemologies.

Goals 1 and 2 focus on information literacy and prebunking and are frequently addressed in the current body of misinformation games. However, there is currently limited exploration of goals 3 and 4, and we provide examples of how games can be framed around those goals in Appendix C. All approaches have benefits and drawbacks, but one might be preferable depending on the context, such as the audience or the type of misinformation.

Intended audience: Who is the intended audience? Games can be created for a (1) general audience, (2) specific audience, or (3) somewhere in between. Designing for general audiences increases the potential reach of the game, while designing for targeted communities creates avenues for designers to utilize narrative affordances. For example, designers could consider creating characters with which target groups may very strongly identify and use those characters as vehicles to explore various aspects of players’ beliefs. This has the potential to engage players in discussions with reduced risk of reactance and counterarguing.

Psychological drivers: What psychological aspects of misinformation does the game touch upon? In our content analysis, we used Shane’s (2020) framework as a basis for identifying a handful of psychological drivers addressed by existing misinformation games (1–5), and we also included one additional driver, emotion, as some games address the influence of emotive information and emotional state on false beliefs (Ecker et al., 2022):

- Third person effect (the tendency to assume that misinformation affects others more than oneself)

- Social pressure (the inclination to repost and believe misinformation shared by one’s social circles)

- Confirmation bias (the tendency to believe information that verifies one’s existing beliefs)

- The rabbit hole effect (a pathway leading towards more extreme misinformation)

- Heuristics (indicators used to make quick judgments)

In addition, designers could also consider other psychological drivers or social factors, such as cognitive dissonance, motivated reasoning, or cognitive miserliness. This would also help establish more specific learning outcomes of the game.

Narrative structure: How does the story progress from beginning to end? We identified three possibilities for the progression of the story: (1) linear, where the story follows a fixed and predictable path, (2) plot twist, where players are abruptly introduced to new information halfway through an otherwise linear story, and (3) branching, where there are multiple paths and multiple endings that the player can discover based on their actions. These choices may have an impact on how people feel at the end of the game and prompt reflection on their role or agency. Furthermore, different modalities may afford different structures. For example, a linear structure would work better for a digital escape room than a physical one, where players can more efficiently examine different parts of the puzzle in parallel.

Setting: Where does the story take place? The story can take place in either realistic or fantastical setting. A realistic setting provides an opportunity for a game to reflect prominent mis- or disinformation issues from the modern day. On the contrary, a fantastical setting may allow for a narrative that can appeal to broader audiences, especially in polarized communities and increase the longevity of the game as it will not feel out of date when new misinformation issues become prevalent. Several existing misinformation games chose a dystopian approach, a fantastical setting that still affords serious conversations about the harm of disinformation present today. Designers could also choose to integrate elements from both: realistic elements to keep the game grounded, but with added fantastical elements to engage younger audiences.

Tone: How does the story convey the topic of misinformation to players? Games can take a humorous tone to lighten the situation, a serious tone to underline the importance of the topic, or incorporate elements of both. This can be determined by considering the audience and the type of misinformation issues that are being discussed in the game. For instance, it would be important to be respectful when incorporating certain misinformation scenarios that harmed people in the real world.

Player agency: Do the game mechanics allow the player to make choices that affect the narrative in significant ways? Based on players’ ability to influence the narrative, the game can allow for different levels of their agency: (1) high agency that permits players to make impactful choices and witness their effects, (2) no agency that keeps players bounded within a set narrative, and (3) limited agency that allows players to make choices, but none that are particularly impactful. In some situations, providing agency may be deemed especially important (e.g., creating a game that empowers players to take action against misinformation), but in other situations, having players experience one particular path is critical for meeting the learning goals (e.g., having players fall for misinformation themselves to discuss the third-person effect).

Player morality: What role does the player character serve within the narrative? In terms of ethical considerations, characters can take on different roles: (1) a hero, by choosing morally correct options, (2) a villain, by actively sowing discord, or (3) a morally gray character, by carrying out questionable actions despite their personal reservations. Taking the perspective of a villain may make the game more engaging, but it might be less suitable in certain misinformation situations. Taking on a role of a morally gray charactermay prompt players to reflect on the choices they make after the gameplay.

Ending: What note does the story finish on? Depending on the finishing note, the story can conclude with (1) a positive ending that might provide players with hope that their actions can make real change, (2) a negative ending that may serve as a reminder of the real harm caused by misinformation, and (3) variable endings, in which the ending is determined by players’ in-game actions. Variable endings may work especially well in social play situations where players get to discuss their choices with others and empathize with the decisions others may have made in the game (Yin & Xiao, 2022).

Player dynamics: How do players interact with each other, if at all? Players’ ability (or lack thereof) to interact with each other during the game determines player dynamics. Many narrative games are individual, but some modalities, such as escape rooms or tabletop games, are suited to social play, in which players can progress through the narrative and construct elements of the story together. Social play could especially be useful for games that require deeper reflection and discussion or that aim to influence players’ attitudes or beliefs, as opposed to more skill- or knowledge-based games.

In sum, the MGND framework allows the designer to carefully consider with which misinformation-related experiences they would like the players to engage through the narrative and game mechanics. This framework could be used in tandem with other game design frameworks, such as the Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics (MDA) framework (Hunicke et al., 2004), to co-design experiences for specific stakeholders and their associated misinformation contexts. We plan to use the MGND framework to co-design culturally specific narratives through our work with universities and libraries internationally.

Evidence

We build from the theoretical background and present three specific hypotheses as to how narrative could supplement the outcomes of playing misinformation games.

Hypothesis 1: Narrative can facilitate identification with opposing viewpoints.

People who have already adopted misinformed beliefs require debunking rather than prebunking. This has led to the suggestion of implementing counter-narratives as a way to deconstruct strongly held beliefs (White, 2022), such as counteracting misinformed beliefs among smokers (Ophir et al., 2020; Sangalang et al., 2019). Evoking a strong emotional response and identification with the main character was shown to have mediating effects on misinformed beliefs (Cohen et al., 2015; de Graaf et al., 2012; Ophir et al., 2020). In game studies, research has shown that perspective taking in virtual environments increases empathy (Estrada Villalba & Jacques-García, 2021). Players are capable of feeling deep emotional attachment to and identification with characters in narrative games (Bopp et al., 2019; Hefner et al., 2007; Sierra Rativa et al., 2020). This increases situational empathy for that character, regardless of their morality (Happ et al., 2013; Iten et al., 2018). Narrative game environments also provide a medium for players to understand other players with whom they may not necessarily identify closely in real life (Burgess & Jones, 2021). Though players may choose different narrative branches, they are capable of empathizing with the rationale behind other players’ decisions without necessarily agreeing with said reasons (Yin & Xiao, 2022).

Hypothesis 2: Narrative can reduce reactance and counterarguing.

Counterarguing against an attempted misinformation correction can strengthen an individual’s belief in it (Ecker, 2017). Narrative’s ability to reduce reactance offers a solution in this respect (Moyer-Gusé, 2008). Slater and Rouner’s (2002) extended Elaboration Likelihood Model, which builds from Petty and Cacioppo’s (2012) Elaboration Likelihood Model, suggests that the cognitive processing of narratives suppresses resistance to persuasive messages contained within the story. The effectiveness of the messaging is associated with the degree of transportation into the story and identification with the characters (Green & Brock, 2000), which led Slater and Rouner (2002) to further argue that transportation and counterarguing are mutually exclusive. In previous work, Slater and Rouner (1996) found that narrative messages were more persuasive than factual arguments, particularly for participants with pre-existing attitudes that countered the persuasive messaging in question. There is also evidence that narratives can overwrite preexisting attitudes regarding controversial issues (Igartua & Barrios, 2012; Slater et al., 2006): Both narrative and effective debunking correctives require an individual to continuously update their mental models (de Vega, 1995; Wilkes & Leatherbarrow, 1988). The process of creating an alternative mental model that replaces the original can reduce the effects of misinformation (Johnson & Seifert, 1994).

Hypothesis 3: Narrative can facilitate educational gains.

Narrative-centered learning environments (Lester et al., 2013) are more effective in promoting enjoyment and knowledge acquisition than traditional game-based learning environments (Abdul Jabbar & Felicia, 2015; Jackson et al., 2018; McQuiggan, Rowe, Lee, et al., 2008; McQuiggan, Rowe, & Lester, 2008; Naul & Liu, 2020). Similar to practitioners building expertise in a domain, games allow players to develop increasingly complex skills through continuously challenging them to achieve mastery in order to progress (Gee, 2003). In addition to skill acquisition, narrative-centered educational games can also spur attitude change. In a review of narrative-centered educational games, skill acquisition (measured in 33 out of 130 reviewed studies) and attitude change (measured in 15 out of 130 reviewed studies) were the most effective educational outcomes (Jackson et al., 2018). This presents an opportunity for designers of misinformation education games to not only allow for skill-building, but to also engage in the attitude changes required for debunking false beliefs.

Methods

Our investigation was two-fold. First, we synthesized findings from misinformation psychology, narrative theory, and game design principles to compile three affordances of narrative in gamified misinformation education contexts. These were presented in the Evidence section and served as guiding principles for our content analysis, described below.

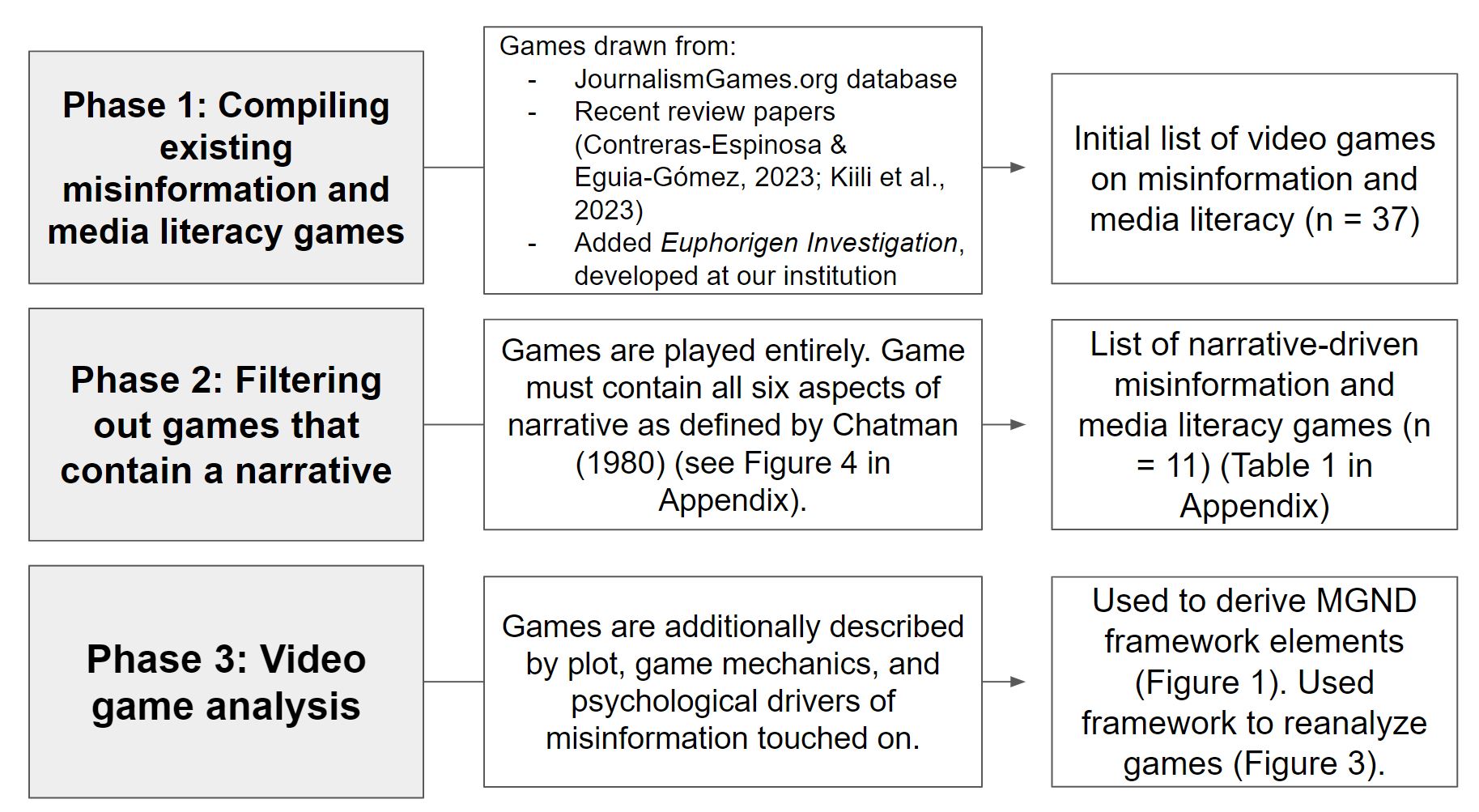

Content analysis

We compiled a list of 37 digital misinformation education games from recent review papers (Contreras-Espinosa & Eguia-Gomez, 2023; Kiili et al., 2023) and from the JournalismGames.org database (Grace & Huang, 2020). We focused on digital games as they are the dominant medium in this space. We excluded games no longer available online or not in English, and we additionally included The Euphorigen Investigation, a recent game developed at our university. We identified 11 games that qualified as narrative-driven (i.e., games containing events, character(s), setting(s), structure, point of view, and time) according to Jackson et al.’s (2018) heuristic. The authors used a consensus model to agree upon the set of games, using the heuristic to make initial selections and discussing conflicts to agreement. The entire process is summarized in Figure 2. We identified and described different aspects of these games’ narrative design, which consequently informed the design of the MGND framework. We then re-analyzed the games using the MGND framework, as presented in Figure 3.

Bibliography

Abdul Jabbar, A. I., & Felicia, P. (2015). Gameplay engagement and learning in game-based learning: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 85(4), 740–779. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315577210

Barzilai, S., & Chinn, C. A. (2020). A review of educational responses to the “post-truth” condition: Four lenses on “post-truth” problems. Educational Psychologist, 55(3), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2020.1786388

Basol, M., Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2020). Good news about bad news: Gamified inoculation boosts confidence and cognitive immunity against fake news. Journal of Cognition, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/joc.91

Bopp, J. A., Müller, L. J., Aeschbach, L. F., Opwis, K., & Mekler, E. D. (2019). Exploring emotional attachment to game characters. In CHI PLAY ’19: Proceedings of the annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play (pp. 313–324). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3311350.3347169

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Burgess, J., & Jones, C. (2021). The female video game player-character persona and emotional attachment. Persona Studies, 6(2), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.21153/psj2020vol6no2art963

Chang, Y. K., Literat, I., Price, C., Eisman, J. I., Gardner, J., Chapman, A., & Truss, A. (2020). News literacy education in a polarized political climate: How games can teach youth to spot misinformation. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(4). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-020

Chatman, S. B. (1978). Story and discourse: Narrative structure in fiction and film. Cornell University Press.

Cohen, J., Tal-Or, N., & Mazor-Tregerman, M. (2015). The tempering effect of transportation: Exploring the effects of transportation and identification during exposure to controversial two-sided narratives. Journal of Communication, 65(2), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12144

Contreras-Espinosa, R. S., & Eguia-Gomez, J. L. (2023). Evaluating video games as tools for education on fake news and misinformation. Computers, 12(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/computers12090188

Dame Adjin-Tettey, T. (2022). Combating fake news, disinformation, and misinformation: Experimental evidence for media literacy education. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2022.2037229

de Graaf, A., Hoeken, H., Sanders, J., & Beentjes, J. W. J. (2012). Identification as a mechanism of narrative persuasion. Communication Research, 39(6), 802–823. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211408594

de Vega, M. (1995). Backward updating of mental models during continuous reading of narratives. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21(2), 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.21.2.373

Domínguez, I. X., Cardona-Rivera, R. E., Vance, J. K., & Roberts, D. L. (2016). The mimesis effect: The effect of roles on player choice in interactive narrative role-playing games. In CHI ’16: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 3438–3449). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858141

Ecker, U. K. H. (2017). Why rebuttals may not work: The psychology of misinformation. Media Asia, 44(2), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01296612.2017.1384145

Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., Kendeou, P., Vraga, E. K., & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

Estrada Villalba, É., & Jacques-García, F. A. (2021). Immersive virtual reality and its use in developing empathy in undergraduate students. In S. Latifi (Ed.), ITNG 2021 18th international conference on information technology-new generations (pp. 361–365). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70416-2_46

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Computers in Entertainment, 1(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1145/950566.950595

Grace, L. D., & Huang, K. (2020, July 8). State of newsgames 2020. JournalismGames.com. https://journalismgames.org/Research%20Overview_newsgames_report_Grace_Haung.pdf

Grace, L. D., & Liang, S. (2024, January 3). Exposure, emotion, and empathy: A theory-informed approach to misinformation and disinformation behavior change through games [Conference proceedings]. 57th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Honolulu, HI, United States. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/107025

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Happ, C., Melzer, A., & Steffgen, G. (2013). Superman vs. BAD man? The effects of empathy and game character in violent video games. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(10), 774–778. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/cyber.2012.0695

Hefner, D., Klimmt, C., & Vorderer, P. (2007). Identification with the player character as determinant of video game enjoyment. In L. Ma, M. Rauterberg, & R. Nakatsu (Eds.), Entertainment computing – ICEC 2007 (pp. 39–48). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74873-1_6

Hunicke, R., LeBlanc, M., & Zubek, R. (2004). MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research [Workshop proceedings]. Game Developers Conference 2001-2004, San Jose, CA, United States. https://cdn.aaai.org/Workshops/2004/WS-04-04/WS04-04-001.pdf

Igartua, J.-J., & Barrios, I. (2012). Changing real-world beliefs with controversial movies: Processes and mechanisms of narrative persuasion. Journal of Communication, 62(3), 514–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01640.x

Iten, G. H., Steinemann, S. T., & Opwis, K. (2018). Choosing to help monsters: A mixed-method examination of meaningful choices in narrative-rich games and interactive narratives. In CHI ’18: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–13). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173915

Jackson, L. C., O’Mara, J., Moss, J., & Jackson, A. C. (2018). A critical review of the effectiveness of narrative-driven digital educational games. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 8(4), 32–49. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGBL.2018100103

Johnson, H. M., & Seifert, C. M. (1994). Sources of the continued influence effect: When misinformation in memory affects later inferences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20(6), 1420–1436. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.20.6.1420

Kahne, J., & Bowyer, B. (2017). Educating for democracy in a partisan age: Confronting the challenges of motivated reasoning and misinformation. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216679817

Kiili, K., Siuko, J., & Ninaus, M. (2023). Tackling misinformation with critical reading games: A systematic literature review. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/8qrx3

Kshetri, N. (2023). The economics of deepfakes. Computer, 56(8), 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2023.3276068

Lester, J. C., Rowe, J. P., & Mott, B. W. (2013). Narrative-centered learning environments: A story-centric approach to educational games. In C. Mouza & N. Lavigne (Eds.), Emerging technologies for the classroom: A learning sciences perspective (pp. 223–237). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4696-5_15

Maertens, R., Roozenbeek, J., Basol, M., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Long-term effectiveness of inoculation against misinformation: Three longitudinal experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 27(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000315

Mahood, C., & Hanus, M. (2017). Role-playing video games and emotion: How transportation into the narrative mediates the relationship between immoral actions and feelings of guilt. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 6(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000084

McQuiggan, S. W., Rowe, J. P., Lee, S., & Lester, J. C. (2008). Story-based learning: The impact of narrative on learning experiences and outcomes. In B. P. Woolf, E. Aïmeur, R. Nkambou, & S. Lajoie (Eds.), Intelligent tutoring systems (pp. 530–539). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-69132-7_56

McQuiggan, S. W., Rowe, J. P., & Lester, J. C. (2008). The effects of empathetic virtual characters on presence in narrative-centered learning environments. In CHI ’08: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1511–1520). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357291

Modirrousta-Galian, A., & Higham, P. A. (2023). Gamified inoculation interventions do not improve discrimination between true and fake news: Reanalyzing existing research with receiver operating characteristic analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152(9), 2411–2437. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001395

Moyer-Gusé, E. (2008). Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory, 18(3), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

Naul, E., & Liu, M. (2020). Why story matters: A review of narrative in serious games. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 58(3), 687–707. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633119859904

Ophir, Y., Romer, D., Jamieson, P. E., & Jamieson, K. H. (2020). Counteracting misleading protobacco YouTube videos: The effects of text-based and narrative correction interventions and the role of identification. International Journal of Communication, 14, 4973–4989. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/15276

Papadamou, K. (2021). Characterizing abhorrent, misinformative, and mistargeted content on YouTube. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2105.09819

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. Springer Science & Business Media.

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2019). The fake news game: Actively inoculating against the risk of misinformation. Journal of Risk Research, 22(5), 570–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2018.1443491

Sangalang, A., Ophir, Y., & Cappella, J. N. (2019). The potential for narrative correctives to combat misinformation. Journal of Communication, 69(3), 298–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz014

Schulzke, M. (2014). Simulating philosophy: Interpreting video games as executable thought experiments. Philosophy & Technology, 27(2), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-013-0102-2

Shane, T. (2020, June 30). The psychology of misinformation: Why we’re vulnerable. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/articles/the-psychology-of-misinformation-why-were-vulnerable/

Sierra Rativa, A., Postma, M., & Van Zaanen, M. (2020). The influence of game character appearance on empathy and immersion: Virtual non-robotic versus robotic animals. Simulation & Gaming, 51(5), 685–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878120926694

Slater, M. D., & Rouner, D. (1996). How message evaluation and source attributes may influence credibility assessment and belief change. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73(4), 974–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909607300415

Slater, M. D., & Rouner, D. (2002). Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Communication Theory, 12(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x

Slater, M. D., Rouner, D., & Long, M. (2006). Television dramas and support for controversial public policies: Effects and mechanisms. Journal of Communication, 56(2), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00017.x

Tang, L., Fujimoto, K., Amith, M. T., Cunningham, R., Costantini, R. A., York, F., Xiong, G., Boom, J. A., & Tao, C. (2021). “Down the rabbit hole” of vaccine misinformation on YouTube: Network exposure study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(1), e23262. https://doi.org/10.2196/23262

van der Linden, S., Maibach, E., Cook, J., Leiserowitz, A., & Lewandowsky, S. (2017). Inoculating against misinformation. Science, 358(6367), 1141–1142. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar4533

Warner, E. L., Basen-Engquist, K. M., Badger, T. A., Crane, T. E., & Raber-Ramsey, M. (2022). The online cancer nutrition misinformation: A framework of behavior change based on exposure to cancer nutrition misinformation. Cancer, 128(13), 2540–2548. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.34218

White, A. (2022). Overcoming “confirmation bias” and the persistence of conspiratorial types of thinking. Continuum, 36(3), 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2021.1992352

Wilkes, A. L., & Leatherbarrow, M. (1988). Editing episodic memory following the identification of error. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 40(2), 361–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724988843000168

Yin, M., & Xiao, R. (2022). How should I respond to “good morning?”: Understanding choice in narrative-rich games. In F. F. Mueller, S. Greuter, R. A. Khot, P. Sweetster, & M. Obrist (Eds.), DIS ’22: Proceedings of the 2022 ACM designing interactive systems conference (pp. 726–744). Association of Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3532106.3533459

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

This work did not involve human subjects, and therefore did not require approval by an institutional review board.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

Replication data is not available for this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the rest of the Loki’s Loop team for inspiring this work. The authors also thank Kate Starbird for her helpful feedback on the first iteration of this project.