Commentary

Reframing misinformation as informational-systemic risk in the age of societal volatility

Article Metrics

0

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

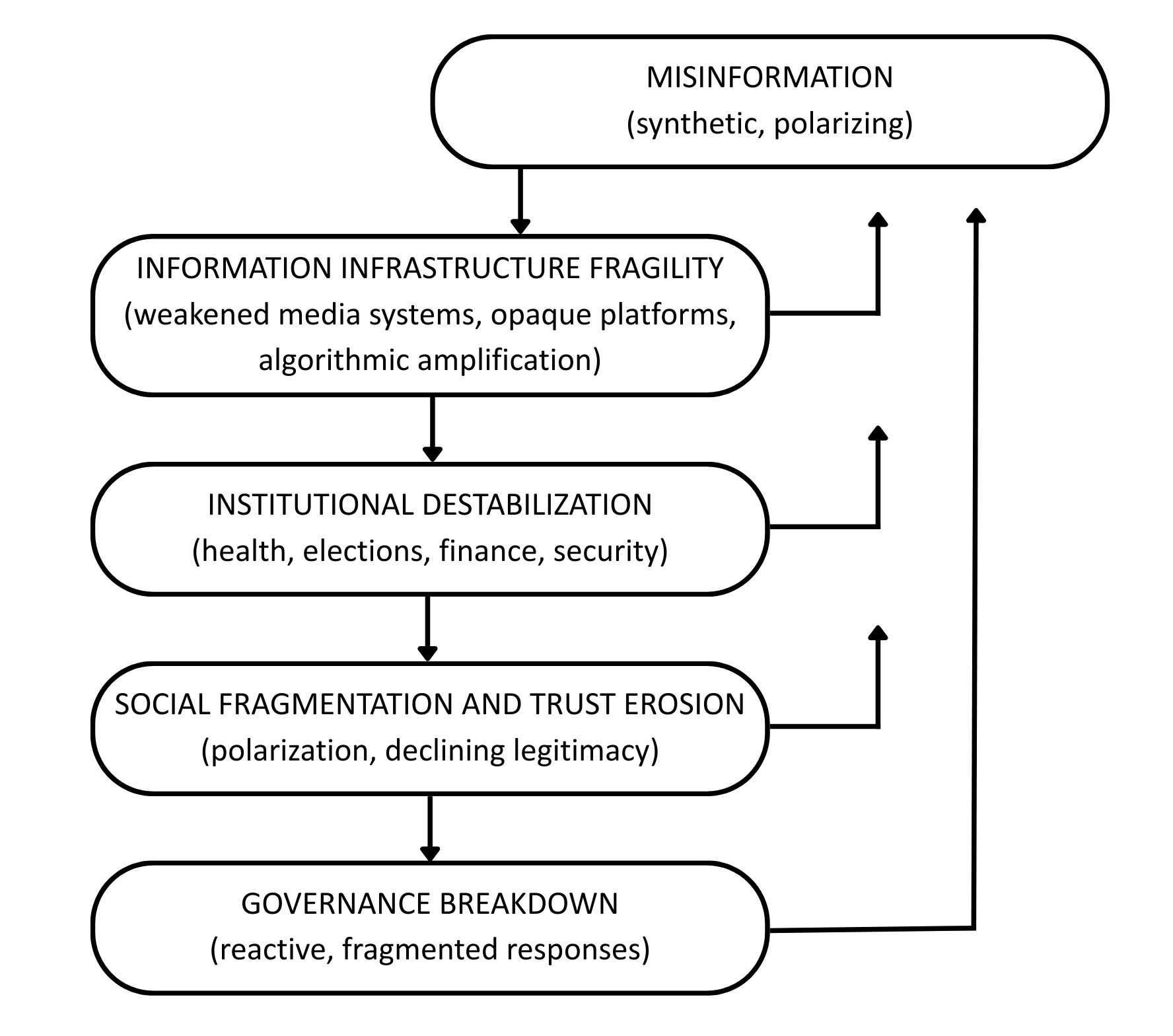

When a bank run, a pandemic, or an election spirals out of control, the spark is often informational. In 2023, rumors online helped accelerate the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. During COVID-19, false claims about vaccines fueled preventable harms by undermining public trust in health guidance, and election lies in the United States fed into the broader dynamics that culminated in the January 6 Capitol attack. These events reveal that misinformation is not just about false or misleading content, but about how degraded information can destabilize entire social systems. To confront this, we must reframe misinformation as an informational-systemic risk that amplifies volatility across politics, health, and security.

Misinformation as a systemic threat

Despite growing concern over misinformation’s effects, most institutional responses remain narrow, focused on content removal, media literacy, or identifying “bad actors.” Prior work has examined how misinformation threatens democracy (Tenove, 2020) and how systemic risks cascade across domains (Schweizer, 2021). Yet risk governance frameworks from finance and climate science remain underused for mapping information cascade mechanisms. This commentary bridges that gap, arguing that misinformation should be recognized as an informational-systemic risk, in which degraded or manipulated information flows can destabilize multiple interdependent social, political, and institutional systems, producing effects that cascade beyond the information environment itself.

Systemic risk, a concept from finance and climate governance, refers to disturbances that spread through networks and produce disproportionate failures across a system (Battison et al., 2012; Renn, et al., 2022). Misinformation exhibits similar cascading dynamics, especially when amplified by emotion, opaque algorithms, and speed. Recent episodes make this clear: viral rumors influenced the rapid 2023 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (Khan et al., 2024), and election misinformation has fueled institutional delegitimization and unrest, from the January 6 attack in Washington (Wang, 2022) to post-election violence in Jakarta in 2019 (Temby, 2022). These examples suggest that feedback loops are recurrent, observable, and potentially destabilizing.

Rather than appearing as isolated incidents, these dynamics reveal how misinformation interacts with fragile systems. Misinformation exploits political distrust, financial volatility, and public health crises, turning points of vulnerability into wider disruption. This is what makes misinformation a systemic risk: it does not remain contained within one domain, but can cascade across sectors, triggering instability in ways that are increasingly difficult to anticipate or control.

Today, we are entering a period of mounting informational fragility. Trust in institutions is declining globally (Valgarðsson et al., 2025), and platform governance remains unevenly regulated across contexts, ranging from structured regulatory frameworks such as the European Union’s (EU) Digital Services Act to environments shaped by heavy-handed regulation or censorship (Jalli, 2024). Against this backdrop of declining institutional trust and uneven platform governance, AI-generated content, from deepfakes to synthetic propaganda, circulates widely at low cost, weakening the system’s resilience. Resilience refers to the capacity of information systems, including platforms, institutions, and publics, to withstand shocks without experiencing critical failures. In practice, this may involve stress-testing algorithms for vulnerability to viral falsehoods, establishing rapid response coordination centers within governments, and investing in trusted communication channels across civil society. Addressing this challenge requires more than correcting individual falsehoods—it demands strengthening the resilience of information systems.

From episodic error to systemic fragility

Traditional approaches tend to treat misinformation as an isolated error rooted in bias, poor judgment, or manipulation. These episodic framings, while useful, struggle to explain how misinformation spreads in environments where institutional, technological, and social systems are deeply interdependent. Systemic risk analysis helps capture these dynamics by showing how disruptions propagate through networks and interact with hidden vulnerabilities. Viewed through this lens, misinformation is not simply misleading content but a structural force that can weaken the trust and legitimacy on which societies depend. The defining feature of systemic risk is not its scale but relational dynamics, particularly its ability to spread through networks, interact with latent vulnerabilities, and push stable systems toward crises (Renn et al., 2022; Schweizer, 2021). Misinformation fits this model. Its danger lies less in single falsehoods than in its capacity to undermine the informational foundations that sustain democratic function, including confidence in science, the legitimacy of elections, and shared historical narratives. Extending systemic risk analysis to the informational domain helps clarify why misinformation should be understood as a structural condition rather than an episodic anomaly.

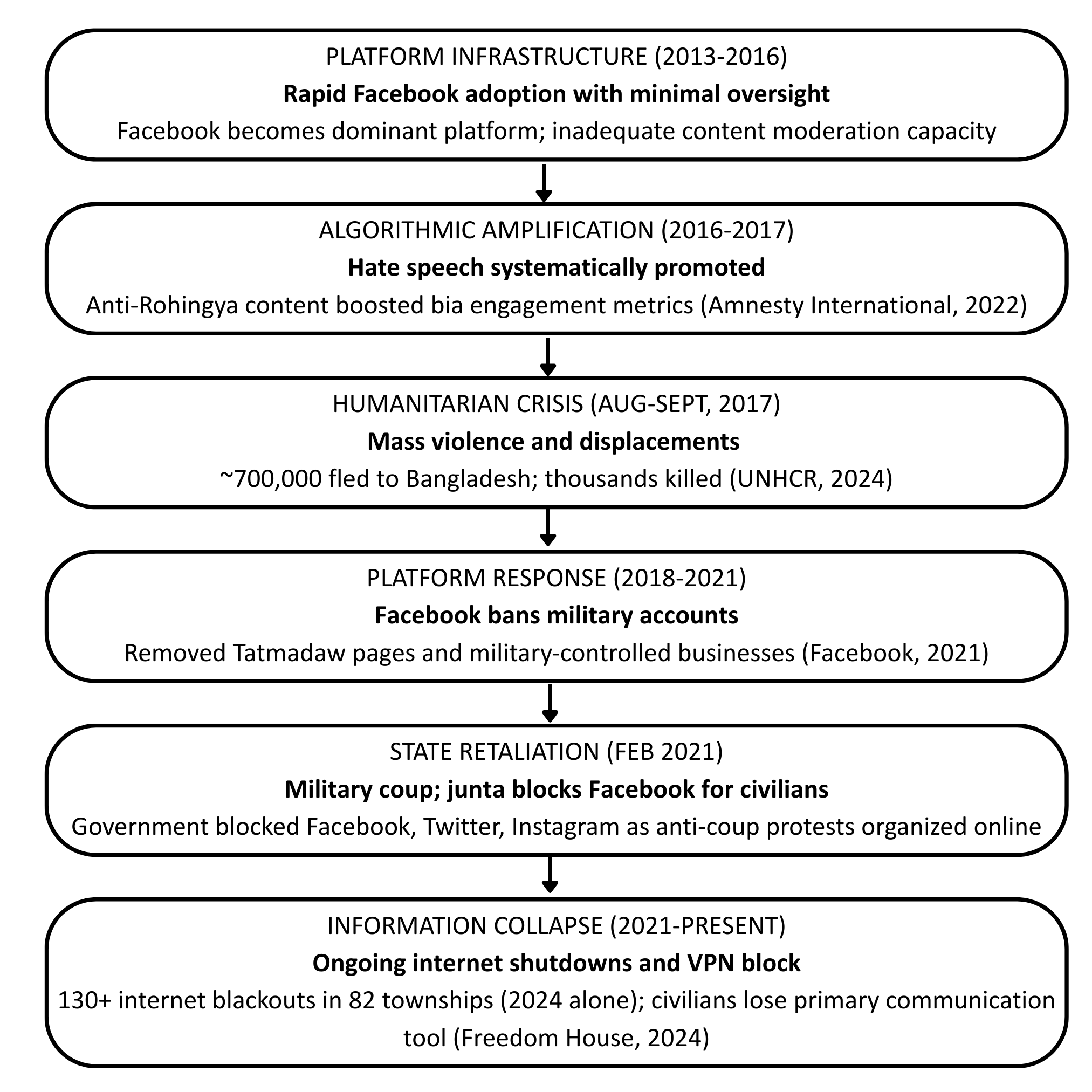

These dynamics are visible across domains. In 2017, false narratives and hate speech circulated on Facebook helped justify attacks against the Rohingya minority in Myanmar, showing how online misinformation can escalate into real-world atrocities (Amnesty International, 2022). In the years that followed, Myanmar authorities imposed internet shutdowns and social media restrictions, citing security concerns but in practice restricting freedom of expression (Human Rights Watch, 2019).

This sequence suggests that responses to misinformation crises can themselves act as catalysts for systemic vulnerability. Facebook’s ban of military accounts prompted junta retaliation that blocked civilians’ primary communication tool while the military continued to exploit the platform for propaganda (Freedom House, 2024). Misinformation can also disrupt disaster responses and climate shocks. During Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, false rumors about shelter policies and mandatory ID checks spread widely on social media, discouraging vulnerable groups from seeking safety and forcing officials to divert resources to debunking misinformation (Hunt, Wang, & Zhuang, 2020). During Australia’s 2019-2020 bushfires, coordinated online narratives exaggerated the role of arson, amplified through the hashtag #ArsonEmergency, distracting attention from climate drivers and weakening support for mitigation measures (Weber et al., 2020). These examples show how misinformation can cascade across environmental hazards, complicating emergency management and climate governance, and contributing to the escalation of natural risks into systemic crises. This commentary extends that pattern of analysis by applying systemic risk governance frameworks from finance and climate studies to examine how misinformation generates cascading failures across domains and should be treated as a cross-infrastructure vulnerability rather than an isolated content problem.

To understand why misinformation tends to cascade across domains, it is necessary to look beyond outcomes and examine the infrastructures that generate them. The sociotechnical perspective shows how platform architectures and design incentives make misinformation not an anomaly but a predictable feature of today’s information environment. Here, infrastructures refer to the shared technical and organizational substrates, such as platforms, networks, and protocols, that enable diverse local systems to operate. Systems, on the other hand, are the locally bounded processes and institutions that function within and through those infrastructures with specific goals and internal interactions (Edwards, 2013).

Misinformation as a sociotechnical threat

Misinformation arises not only from individual behavior or malign actors but also from the infrastructures that govern digital communication. Platform research finds that algorithmic design and advertising logic systemically privilege attention-grabbing content, regardless of accuracy (Gillespie, 2018; Vaidhyanathan, 2018). Recommendation systems optimized for engagement can amplify emotionally charged posts, while monetization models reward divisive content that keeps users active. Far from neutral, these systems normalize the circulation of misleading content by embedding it into everyday communication flows.

Studies of YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter indicate that attention-driven architectures promote emotionally charged and polarizing material, often elevating misinformation above verified information (Tufekci, 2015; Vosoughi et al., 2018). Such dynamics make misinformation a predictable outcome of sociotechnical design rather than an anomaly.

As these architectures evolve, the rapid integration of generative AI into content production and distribution further increases existing risks. Synthetic text, images, and video, produced at scale and often indistinguishable from authentic material, can intensify misinformation campaigns (Paris & Donovan, 2019; Weidinger et al., 2021). Detection systems often lag behind innovation, while moderation practices remain fragmented and uneven across platforms and can leave exploitable gaps. The concern is not only that people may believe false claims, but that digital systems themselves are structured in ways that enable, incentivize, and monetize them. Effective governance must therefore address both the technical architectures that accelerate misinformation and the broader social conditions that allow it to persist.

Deepfakes, AI, and the informational arms race

Deepfakes illustrate how generative AI is compounding systemic risk in the information environment. Unlike earlier manipulated media, deepfakes can generate audio and video that appear indistinguishable from authentic recordings, creating major challenges for verification (Paris & Donovan, 2019). These threats to evidentiary trust affect not only individuals but also courts, newsrooms, and democratic institutions that depend on credible records. By complicating verification processes, deepfakes can amplify the cascading dynamics of systemic risk, potentially weakening institutional legitimacy, undermining governance, and heightening geopolitical insecurity.

These tools are appearing more frequently in strategic information operations. During Taiwan’s 2024 presidential election, a fabricated audio clip alleging that a senior politician accused Lai Ching-te of embezzlement was confirmed as a deepfake. The same campaign used spliced and overdubbed video clips to distort public statements. Reportedly linked to state-aligned media networks, these tactics show how synthetic media is being adapted for election interference, straining fact-checking systems and eroding trust in democratic processes (Hung et al., 2024).

The United States has faced similar risks. In May 2025, the FBI warned that AI-generated voice messages and texts were being used to impersonate senior officials in attempts to harvest credentials and compromise networks (Vicens, 2025). Such incidents suggest that deepfakes are evolving beyond curiosities or isolated hoaxes and are increasingly integrated into the infrastructure of political disruption. Their spread challenges the traditional notions of proof, undermines verification norms, and deepens uncertainty in everyday discourse. Deepfakes, therefore, may transform misinformation from isolated episodes of deception into a bigger systemic risk. By threatening the evidentiary foundations on which institutions and publics rely, synthetic media can accelerate cascades across domains, turning fragile systems in health, finance, and politics into contested arenas over reality.

The limits of behavioral fixes

In response to the global misinformation crisis, education and media literacy remain the most common solutions. The assumption is that if people are taught to spot falsehoods, they will be more resilient to manipulation. This approach is appealing because it is scalable, empowering, and politically uncontroversial. Yet in today’s fragmented and fast-moving environment, its limits are increasingly evident.

Misinformation is not merely about what people believe, but also about the systems that shape those beliefs. Even highly informed individuals are continually exposed to misleading content, some algorithmically prioritized and some synthetically generated, much of it circulating through attention-driven economies (Guess, et al., 2020; Pennycook & Rand, 2021). Knowing how to evaluate sources cannot stop an AI-generated video from going viral or an emotionally charged conspiracy from dominating timelines. The challenge lies less in individual capacity than in the structural conditions that overwhelm it (Guess & Lyons, 2020).

Many interventions rely on a “deficit model” that assumes people fall for misinformation because they do not know better. Yet research shows that belief in falsehoods is often driven by identity, emotion, and belonging rather than ignorance (Bail, 2022; Lewandowsky et al., 2017; Kahan, 2017). People share false claims not simply because they are misled, but because those claims feel true, reinforce loyalties, or signal political alignment. No fact check can easily compete with that kind of resonance, especially when reinforced by algorithmic amplification and social feedback (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010).

The tension between social motivations for sharing and systemic risk is crucial. Systemic risk does not necessarily require widespread belief in false claims; it can emerge through multiple pathways. Widespread circulation (regardless of individual belief) tends to degrade information quality and increase the cost of discerning truth (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Even limited belief among key actors like policymakers, journalists, or health officials may trigger cascading failures. Endemic uncertainty can constrain institutional decision-making, while resources diverted to fact-checking and counter-messaging often weaken institutional capacity (Helbing, 2013). Social sharing thus can amplify rather than mitigate systemic risk by accelerating distribution and saturating information networks, making misinformation a structural vulnerability that extends beyond individual credulity.

Behavioral interventions remain valuable but cannot serve as the primary response. They are too reactive, slow, and overly focused on individuals while neglecting the infrastructures that reward virality over accuracy. Media literacy programs do not change the fact that content moderation remains inconsistent, underfunded, and politicized. If misinformation is a system-wide vulnerability, responses should include regulatory frameworks that address design incentives, algorithmic transparency, and platform accountability. Information integrity should be treated as a public good rather than an individual responsibility.

Reframing governance for systemic resilience

If misinformation is embedded in sociotechnical systems rather than isolated content, governance responses must evolve accordingly. The challenge is not only what people post, or believe, but how digital infrastructures are designed, governed, and incentivized (Chesterman, 2025). Systemic risks demand systemic thinking, yet current strategies remain misaligned with the scale and complexity of the threat (Helbing, 2013).

Governance today is fragmented and often reactive. Content moderation struggles to keep pace with the volume and velocity of falsehoods. Laws targeting misinformation are frequently overly broad, vulnerable to political misuse, or narrowly focused on criminal intent. International coordination remains limited, while the platforms that shape global discourse operate across borders with uneven transparency and accountability (Gorwa, 2019). This mismatch creates conditions under which misinformation flourishes not only because it is persuasive but because the environment rewards its circulation.

Enhancing resilience begins by recognizing platforms as critical infrastructure rather than neutral conduits. Algorithmic design, moderation, and enforcement policies influence democratic processes, public health, and geopolitical stability. Operationally, platforms could be required to conduct adversarial testing that simulates how false narratives about elections or health might spread through recommendation systems, identifies amplification points, and demonstrates mitigation capacity, similar to financial stress tests. Although some platforms conduct internal testing, transparency and enforcement remain limited (Urman & Makhortykh, 2023).

The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) requires large online platforms to conduct annual systemic risk assessments and independent audits of their content-governance practices (European Commission, 2022a). While the companion Digital Markets Act (DMA) addresses competition and gatekeeper power, comparable obligations remain rare outside the EU (European Commission, 2022b). Effective implementation depends on international coordination, as platforms operate across jurisdictions and unilateral regulations risk regulatory gaps.

Just as governments regulate financial systems to prevent cascading economic failure, there is a case for meaningful oversight of how information is distributed, ranked, and monetized (Gillespie et al., 2020). Building systemic resilience, therefore, requires infrastructural reforms, platform accountability, and cross-border cooperation. Without stronger coordination, interventions will remain reactive, leaving societies vulnerable to future informational shocks.

Bibliography

Amnesty International. (2022, September 29). Myanmar: Facebook’s systems promoted violence against Rohingya; Meta owes reparations – new report. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/09/myanmar-facebooks-systems-promoted-violence-against-rohingya-meta-owes-reparations-new-report/

Bail, C. (2022). Breaking the social media prism: How to make our platforms less polarizing. In Breaking the social media prism. Princeton University Press.

Battiston, S., Puliga, M., Kaushik, R., Tasca, P., & Caldarelli, G. (2012). Debtrank: Too central to fail? Financial networks, the fed and systemic risk. Scientific Reports, 2(1), 541. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00541

Chesterman, S. (2025). Lawful but awful: Evolving legislative responses to address online misinformation, disinformation, and mal-information in the age of generative AI. The American Journal of Comparative Law, 72(4), 933–965. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcl/avaf020

Edwards, P. N. (2013). A vast machine: Computer models, climate data, and the politics of global warming. MIT Press.

European Commission. (2022a). The Digital Services Act: Ensuring a safe and accountable online environment. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/digital-services-act_en

European Commission. (2022b). The Digital Markets Act: Ensuring fair and open digital markets. https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/about-dma_en

Facebook. (2021, February 11). An update on the situation in Myanmar. https://about.fb.com/news/2021/02/an-update-on-myanmar/

Freedom House. (2024). Myanmar: Freedom on the Net 2024 Country Report. https://freedomhouse.org/country/myanmar/freedom-net/2024

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

Gillespie, T., Aufderheide, P., Carmi, E., Gerrard, Y., Gorwa, R., Matamoros-Fernández, A., Sinnreich & Myers West, S. (2020). Expanding the debate about content moderation: Scholarly research agendas for the coming policy debates. Internet Policy Review, 9(4), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1512

Gorwa, R. (2019). What is platform governance? Information, Communication & Society, 22(6), 854–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1573914

Guess, A. M., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2020). Exposure to untrustworthy websites in the 2016 US election. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0833-x

Guess, A., & Lyons, B. (2020). Misinformation, disinformation, and online propaganda. In N. Persily & J. A. Tucker (Eds.), Social media and democracy (pp. 10–33). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108890960

Helbing, D. (2013). Globally networked risks and how to respond. Nature, 497(7447), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12047

Human Rights Watch. (2019, June 28). Myanmar: Internet shutdown risks lives. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/28/myanmar-internet-shutdown-risks-lives

Hung, C. L., Fu, W. C., Liu, C. C., & Tsai, H. J. (2024). AI disinformation attacks and Taiwan’s responses during the 2024 presidential election. Graduate Institute of Journalism, National Taiwan University. https://www.thomsonfoundation.org/media/268943/ai_disinformation_attacks_taiwan.pdf

Hunt, K., Wang, B., & Zhuang, J. (2020). Misinformation debunking and cross-platform information sharing through Twitter during Hurricanes Harvey and Irma: A case study on shelters and ID checks. Natural Hazards, 103(1), 861–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04016-6

Jalli, N. (2024). Holding social media companies accountable for enabling hate and disinformation. Perspective, 2024/51. ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute Singapore. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2024-51-holding-social-media-companies-accountable-for-enabling-hate-and-disinformation-by-nuurrianti-jalli/

Kahan, D. M. (2017). Misconceptions, misinformation, and the logic of identity-protective cognition. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2973067

Khan, M. H., Hasan, A. B., & Anupam, A. (2024). Social media-based implosion of Silicon Valley Bank and its domino effect on bank stock indices: Evidence from advanced machine and deep learning algorithms. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 14(1), Article 110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-024-01270-5

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Paris, B., & Donovan, J. (2019, September 18). Deepfakes and cheap fakes. Data & Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/library/deepfakes-and-cheap-fakes/

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(5), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007

Renn, O., Laubichler, M., Lucas, K., Kröger, W., Schanze, J., Scholz, R. W., & Schweizer, P. J. (2022). Systemic risks from different perspectives. Risk Analysis, 42(9), 1902–1920. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13657

Schweizer, P. J. (2021). Systemic risks–concepts and challenges for risk governance. Journal of Risk Research, 24(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2019.1687574

Temby, Q. (2022). Disinformation, post-election violence and the evolution of anti-Chinese sentiment. In M. Supriatma & H. Yew-Foong (Eds.), The Jokowi-Prabowo elections 2.0 (pp. 90–106). ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

Tenove, C. (2020). Protecting democracy from disinformation: Normative threats and policy responses. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 517–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612209187

Tufekci, Z. (2015). Algorithmic harms beyond Facebook and Google: Emergent challenges of computational agency. Colorado Technology Law Journal, 13(2), 203–218.

Vicens, A. J. (2025, May 15). Malicious actors use AI‑generated voice messages to impersonate senior U.S. officials. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/malicious-actors-using-ai-pose-senior-us-officials-fbi-says-2025-05-15/

Urman, A., & Makhortykh, M. (2023). How transparent are transparency reports? Comparative analysis of transparency reporting across online platforms. Telecommunications Policy, 47(3), Article 102477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2022.102477

UNHCR. (2024, August 22). Rohingya refugee crisis explained. https://www.unrefugees.org/news/rohingya-refugee-crisis-explained/#RohingyainBangladesh

Vaidhyanathan, S. (2018). Antisocial media: How Facebook disconnects us and undermines democracy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190056544.001.0001

Valgarðsson, V., Jennings, W., Stoker, G., Bunting, H., Devine, D., McKay, L., & Klassen, A. (2025). A crisis of political trust? Global trends in institutional trust from 1958 to 2019. British Journal of Political Science, 55, Article e15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000498

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Wang, J. (2022). The US Capitol riot: Examining the rioters, social media, and disinformation [Master’s thesis, Harvard University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/u-s-capitol-riot-examining-rioters-social-media/docview/2666566172/se-2

Weber, D., Nasim, M., Falzon, L., & Mitchell, L. (2020, October). #ArsonEmergency and Australia’s “Black Summer”: Polarisation and misinformation on social media. In M. van Dujin, M. Preuss, V. Spaiser, F. Takes, & S. Verberne (Eds.), Disinformation in open online media. Second multidisciplinary international symposium, MISDOOM 2020, Leiden, The Netherlands, October 26–27, 2020, proceedings (pp. 159–173). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61841-4_11

Weidinger, L., Mellor, J., Rauh, M., Griffin, C., Uesato, J., Huang, P., Cheng, M., Glaese, M., Balle, B., Kasirzadeh, A., Kenton, Z., Brown, S., Hawkins, W., Stepleton, T., Biles, C., Birhane, A., Haas, J., Rimell, L., Hendricks, L. A., … Gabriel, I. (2021). Ethical and social risks of harm from language models. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.04359

Funding

No funding has been received to conduct this research.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.