Peer Reviewed

Overlooking the political economy in the research on propaganda

Article Metrics

5

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Historically, scholars studying propaganda have focused on its psychological and behavioral impacts on audiences. This tradition has roots in the unique historical trajectory of the United States through the 20th century. This article argues that this tradition is quite inadequate to tackle propaganda-related issues in the Global South, where a deep understanding of the political economy of propaganda and misinformation is urgently needed.

Research Questions

- What is the dominant approach to studying online propaganda in the context of the Global South?

- What are the limitations of this approach?

Essay Summary

- During the 20th century, funding from the U.S. government and corporate entities oriented the field of mass communication towards studying psychological and behavioral impacts of media on audiences because such research was beneficial to these funders. This orientation is the dominant paradigm in the field.

- A bulk of research on misinformation and propaganda since 2016 is situated in this intellectual legacy.

- A thematic meta-analysis – of recent literature on online propaganda in the context of the Global South, and 20 Facebook-funded research projects in 2018 – shows that research is overwhelmingly focused on the psychological and behavioral impacts of propaganda. This research advocates for promoting “media literacy” and helping citizens “inoculate” themselves against propaganda.

- This approach has limited use in tackling propaganda in the Global South. It not only oversimplifies “media literacy,” but also fails to examine, quite crucially, how the state, corporations, and media institutions interact – the political economy of propaganda.

- Further, scholars need to reflect on how entities such as Facebook fund such research to deflect scrutiny of their institutional role in propaganda-related violence in the Global South.

Implications

Researchers studying mass communication, including social media, often focus on the media’s psychological and behavioral impacts on audiences to the detriment of an institution-level study of mass communication. The reason for such an orientation lies in the history of mass communication research in the United States amidst the global wars and social turmoil of the twentieth century. During this period, research agendas took on an “administrative” approach in order to aid those in governments and corporations in using communication channels to better influence their audiences (Lazarsfeld, 1941).1Lazarsfeld, a “founding father” of the field, describes the administrative paradigm as “carried through in the service of some kind of administrative agency of public or private character” (Lazarsfeld, 1941, p. 8) with a purpose to “sell goods, or to raise the intellectual standards of the population, or secure an understanding of government policies” (Lazarsfeld, 1941, p. 2). The administrative research paradigm (henceforth “administrative paradigm”) conceptualizes communication as “a sender sending a message through a channel to affect audiences.” In this linear, mechanical, and mathematical formulation, each of the pieces – “sender,” “message,” “channel,” and “audiences” – are objects of study. “Media effects” research combines these pieces by studying how various types of messages and channels influence audiences. The administrative paradigm is the dominant paradigm within the field.

Although the research outside of the administrative paradigm is vast (as described later in this section), the dominant paradigm overlooks the political economy of communication or an institution-level analysis – how the state and corporate interests influence media institutions and shape “communication.” These priorities have significant implications, especially regarding propaganda in the Global South. For example, scholars have rarely examined Facebook’s institutional role in the genocide in Myanmar. But before describing these implications further, it is useful to briefly historicize the administrative paradigm.

Historicizing the administrative paradigm

Over the course of the twentieth century, support from two entities was crucial to solidify administrative research as the dominant paradigm within communication research in the U.S. – corporate interests such as the Rockefeller Foundation, and the U.S. government (Pooley, 2008). After observing widespread public susceptibility to propaganda during WWI, many prominent scholars in the U.S. envisioned a technocratic or “managed” democracy (Gary, 1999, pp. 15–54; Glander, 2000, pp. 1–37; Sproule, 1997, pp. 54–74). With corporate funding and governmental aid, scholars started conducting media-effects research, which laid the foundations of the modern advertising and public relations industry as well as more sophisticated propaganda efforts by the U.S. government (Pooley, 2008). By WWII, a network of administrative paradigm scholars had emerged which helped mobilize U.S. citizens for the war and countered Nazi propaganda on behalf of the Roosevelt administration (Glander, 2000, pp. 38–55). Prominent paradigm scholars made the utility of media-effects research clear in the statement that “[public] consent will require unprecedented knowledge of the public mind and of the means by which leadership can secure consent” (Gary, 1996, pp. 139–140). The result was a proliferation of media-effects research and the inception of prominent journals such as Public Opinion Quarterly, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation (Gary, 1996).

The Cold War was momentous in establishing mass communication as a distinct field, with administrative research as its dominant paradigm (Simpson, 1994). As the two global superpowers raced to control the “Third World,” the U.S. government poured in unprecedented funding into media-effects research, which back then was more appropriately called “psychological warfare” research.2Over time, terms such as “propaganda” and “psychological warfare” were replaced by more innocuous-sounding words such as “persuasion” even though the underlying research orientation has remained unchanged (Simpson, 1994; Sproule, 1997). In 1952, for example, 96% of the reported funding in communication research was from the U.S. military (Simpson, 1994, p. 52). This research directly shaped U.S. psychological warfare efforts in “Third World” countries such as Iran (Simpson, 1994, p. 56). In addition, the U.S. government’s massive support expanded the aforementioned network of administrative paradigm scholars; helped place these scholars in high academic positions with control over scholarly publishing and rank and tenure decisions; and the establishment of key academic journals (Simpson, 1994, p. 9).

Turning to the present, the key point is that contemporary research is shaped by this history: which texts are considered “classics,” who the “founding fathers” are, the top academic journals and their research orientations, and the research questions that generations of scholars have deemed important. That is, academic inquiry operates on a terrain shaped by history and contemporary political economy, rather than in a vacuum.3This is, of course, not unique to the field of communication, but also psychology, area studies, anthropology, development studies, and social sciences in general. See the “Introduction” in Universities and Empire (Simpson, 1998). Furthermore, states’ and corporations’ desire to fund administrative research is not just a phenomenon of the past. Rather, it is fundamental to their interests – they want to use mass communication for political campaigns, advertising, etc.; to educate, persuade, manipulate, or control their subjects.

Limitations of current research

It is in this context that propaganda research has boomed since the 2016 U.S. election. The thematic meta-analysis presented in this paper provides evidence of multiple limitations in the bulk of this research in the context of the Global South:

- Theoretical: The research is primarily focused on media-effects – it investigates individuals’ susceptibility to propaganda.

- Policy: The research largely conceptualizes online platforms as neutral, and therefore the policy recommendations place the burden of responsibility onto individuals – suggesting that governments should conduct “media literacy” campaigns and recommending how to “inoculate”4To quote Roozenbeek & van der Linden (2020) from this journal, “inoculation theory” – which has a plethora of literature on it – uses a medical analogy to posit that “preemptively exposing someone to a weakened version of a particular misleading argument prompts a process that is akin to the production of ‘mental antibodies,’ which make it less likely that a person is persuaded by the ‘real’ manipulation later on.” Their research was funded by the U.S. State Department and U.S. Department of Homeland Security (and conducted on U.S. citizens). This article illustrates the historical patterns described in this article quite aptly; see Roozenbeek et al. (2020) for another example. citizens against propaganda. Entities such as Facebook have generously funded such research when facing scrutiny of their institutional role in propaganda-fueled violence in the Global South.

- Methodological: The research is methodologically limited by the administrative paradigm; primarily to conducting media-effects experiments and secondarily to doing content analysis5The history of content analysis and its relationship with the administrative paradigm is interesting. The U.S. government promoted content analysis within the administrative paradigm during the Cold War so that it can identify propaganda from rival institutions and get insights into those institutions. Interestingly, researchers working for the U.S. government seriously questioned if content analysis can help in making inferences about institutions at all (Simpson, 1994, p. 88; Sproule, 1997, pp. 193–196). of online propaganda. Largely absent are methodologies such as policy analysis, interviews, ethnographies, historical analysis, etc.

- Geographical: Research is overwhelmingly focused on the Global North.

The following two cases illustrate the alarming situation in the Global South, along with some key institution-level issues therein, which the administrative paradigm is theoretically unequipped to tackle. In Myanmar, the UN fact-finding mission declared that Facebook played a “determining role” in the Rohingya genocide leading to the exodus of more than 800,000 Rohingya Muslims and a massive humanitarian crisis in South Asia (Miles, 2018). But the key issue of Facebook’s institutional role is rarely examined by communication scholars (some scholarship breaks this trend; see Fink, 2018; Sablosky, 2021).

In India, Hindu nationalist propaganda on Facebook and Facebook-owned WhatsApp has led to harassment, hate speech, lynchings, and pogroms against Muslims and lower castes (Muslim Advocates & GPAHE, 2020; Soundararajan et al., 2019). Here, a key dynamic is that India is the largest market for Facebook,6328 million and 400 million Indians use Facebook and WhatsApp, respectively (Perrigo, 2020). and Facebook appears to be reluctant to curb propaganda at the expense of its profits. For instance, to avoid upsetting the ruling Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Facebook has allowed hate speech by BJP politicians to remain on its platform in violation of its own policies (Purnell & Horwitz, 2020). It is difficult to expect institutional accountability when BJP-linked people run the Facebook India office (ibid.).

Suggested interventions

This paper suggests the following interventions. First, the dominance of the administrative paradigm exists alongside a theoretically and methodologically vast and rich literature, which adopts other approaches to studying mass communication in the Global North such as: online content moderation (Gillespie, 2018), regulation of social media companies (Napoli, 2019), propaganda ecosystems (Benkler et al., 2018), the role of algorithms (Caplan & boyd, 2018; Noble, 2018), and the political economy of communication (Hindman, 2008; McChesney, 2015; Pickard, 2019). But it is the dominant paradigm – its theoretical orientation and methodology – that is most frequently applied to study online propaganda in the Global South. Less common are approaches dealing with important questions in the Global South of content moderation and hate speech (Sablosky, 2021), the political economy of the internet (Athique & Parthasarathi, 2020), internet regulation (Parthasarathi & Agarwal, 2020; Rajkhowa, 2015), internet access (Moyo & Munoriyarwa, 2021; Mukherjee, 2019; Nothias, 2020), and theorizations of what “fake news” might mean in the Global South (Wasserman, 2020). Scholars need to fill these gaps urgently.

Second, “media literacy” in the context of the Global South needs to be defined with a democratic ethos. There is a tendency in existing research to persistently connect individuals’ characteristics (education, income, identity etc.) to their susceptibility to online propaganda. This tendency extends the discipline’s described historic legacy of facilitating imperialism and statist–corporatist control. Instead, scholars need to explore how individuals can be empowered to participate democratically in policymaking on these issues (Hasebrink, 2012;7Also see the entire corresponding special issue of Medijske Studije. Horowitz & Napoli, 2014).

Third, scholars need to be cognizant of the political economy of knowledge production – how institutions such as Facebook promote administrative research which takes scholarly attention away from Facebook’s institutional role in propaganda-related violence.8As explained earlier, this is part of a larger historic trend. Another example is the Rockefeller Foundation awarding a $67,000 grant in 1937 to study media-effects in the U.S. – the grant came during the formative period for the discipline, and explicitly forbade research on questions of the political economy of communication (Pooley, 2008, p. 51). The prevalence of a research paradigm need not be in proportion to its normative value or theoretical sophistication.

Evidence

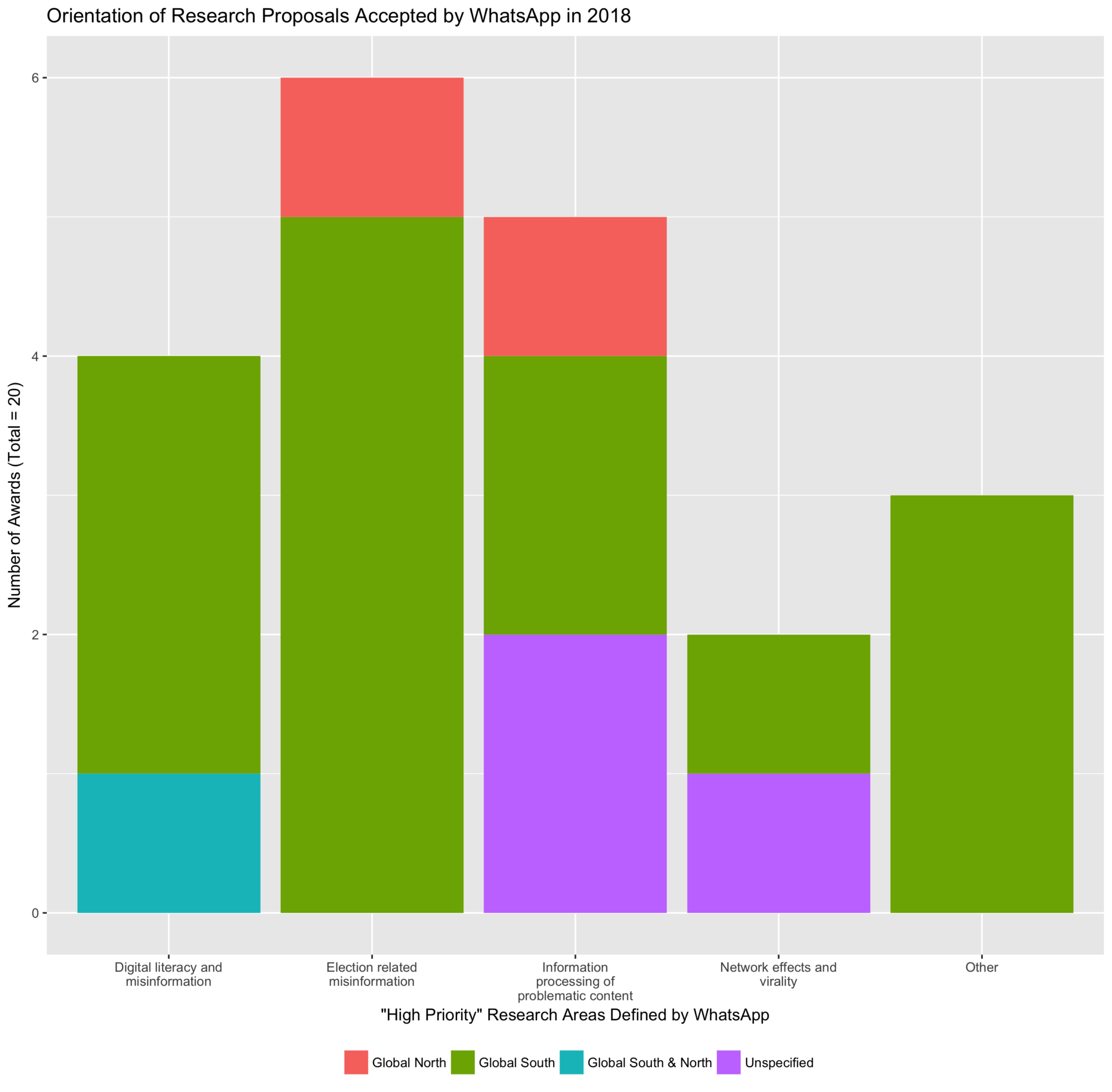

Finding 1: Agendas of research projects funded by Facebook-owned WhatsApp to study misinformation.

In July 2018, Facebook-owned WhatsApp came under heavy scrutiny globally after a series of WhatsApp-fueled lynchings occurred in India (Gowen, 2018). WhatsApp responded with a massive public relations campaign – on radio, television, print media, and the internet – projecting WhatsApp/Facebook as a neutral actor that was committed to helping the community fight misinformation (Creech, 2020; Indo-Asian News Service, 2018; The Indian Express, 2018). Further, WhatsApp invited proposals for “WhatsApp Research Awards for Social Science and Misinformation,” which was widely publicized in the news media. In November 2018, WhatsApp awarded $50,000 to 20 research proposals, totaling $1 million.

A thematic meta-analysis was done to understand the research focus of this $1 million grant using: (1) WhatsApp’s definitions of “high priority” areas9The initial announcement included a category called “Detecting problematic behavior within encrypted systems,” but no research awards were given under it. This category was defined as “Examine technical solutions to detecting problematic behavior within the restrictions of and in keeping with the principles of encryption.” under which it invited proposals, and thereby outlined research agenda(s); (2) The abstracts of all 20 accepted proposals (and every proposal’s stated “high priority” area) from which the more specific research and geographic focus of individual proposals could be ascertained.

Overall, the geographic focus is encouraging; 75% of proposals are on the Global South. However, each “high priority” area (listed below) and the proposals therein are confined to the administrative paradigm:

- Information processing of problematic content: WhatsApp defined this as examining how “social, cognitive, and information processing variables relate to the content’s credibility, and the decision to share that content with others;” that is, media-effects research. For example, one study will compare how users react to fake news in various formats (text-only, audio-only, and video) in India.

- Election-related misinformation: Proposals under this category predominantly undertake media-effects research but emphasize electoral politics. For example, studies will focus on how users get impacted by political information, how they have political conversations, etc.

- Digital literacy and misinformation: WhatsApp defines this as “the relation between digital literacy and vulnerability to misinformation on WhatsApp.” Although this is media-effects research, the focus is more on application (literacy) rather than on advancing theory. One study will examine “how vulnerability to fake news is affected by socioeconomic, demographic, or geographical factors” across nine states in India. Another will test the effectiveness of a game-based intervention to “inoculate” WhatsApp users against fake news.

- Network effects and virality: WhatsApp defined this as “the spread of information through WhatsApp networks.” One study will explore how users process religious information, and another will examine how WhatsApp users and their networks coevolve as misinformation diffuses through the network.

In sum, when Facebook-owned WhatsApp faced intense scrutiny on its institutional role in propaganda-related violence in the Global South, it responded by funding administrative research – framing the issue as users’ susceptibility to propaganda and lack of media literacy.

This approach overlooks WhatsApp’s far more complex role in the Global South. For example, “encrypted” platforms such as WhatsApp do not protect everyone equally – while Hindu nationalist groups in India organize violence on WhatsApp with impunity (Purohit, 2019), peaceful protestors are prosecuted (Mahaprashasta, 2020).10Although the Indian government and other actors have hacked into WhatsApp in the past, the issue is typically not related to breaking WhatsApp’s encryption – police reports are filed using screenshots of WhatsApp messages, phones are seized, etc. Right-wing authoritarians have leveraged WhatsApp extensively for their political campaigns (Avelar, 2019; Perrigo, 2019; Vaidhyanathan, 2018, pp. 186–195). There is also a larger issue of Facebook pushing its services, such as WhatsApp, without establishing a functional internal infrastructure for handling civil rights issues.11Facebook’s failure in this regard is perhaps best documented in the Global North. See Murphy and Cacace (2020). For instance, Facebook makes its website/services cheaper to access compared to other websites in the Global South,12This project by Facebook – which violates net neutrality – is called “Internet.org” or “Free Basics,” see Nothias (2020). Recently, Facebook appointed the vice-president of Internet.org to run WhatsApp. which has made Facebook/WhatsApp ubiquitous in countries such as Myanmar (Vaidhyanathan, 2018, pp. 194–195). The issues of internet access, digital literacy, and propaganda are interconnected and need to be studied holistically (Moyo & Munoriyarwa, 2021; Mukherjee, 2019; Nothias, 2020).

Lastly, the political economy of knowledge production should be noted here. Following a series of WhatsApp-fueled lynchings in India in 2018, Facebook provided $1 million for administrative research. In contrast, when an investigative report in 2020 revealed the collusion between Facebook and India’s Hindu nationalist government (Purnell & Horwitz, 2020), no research grant was awarded to study similar institution-level phenomena in the Global South. Through research funding, Facebook appears to have strategically marginalized the institutional dimensions within these contexts, with obvious consequences for knowledge production.

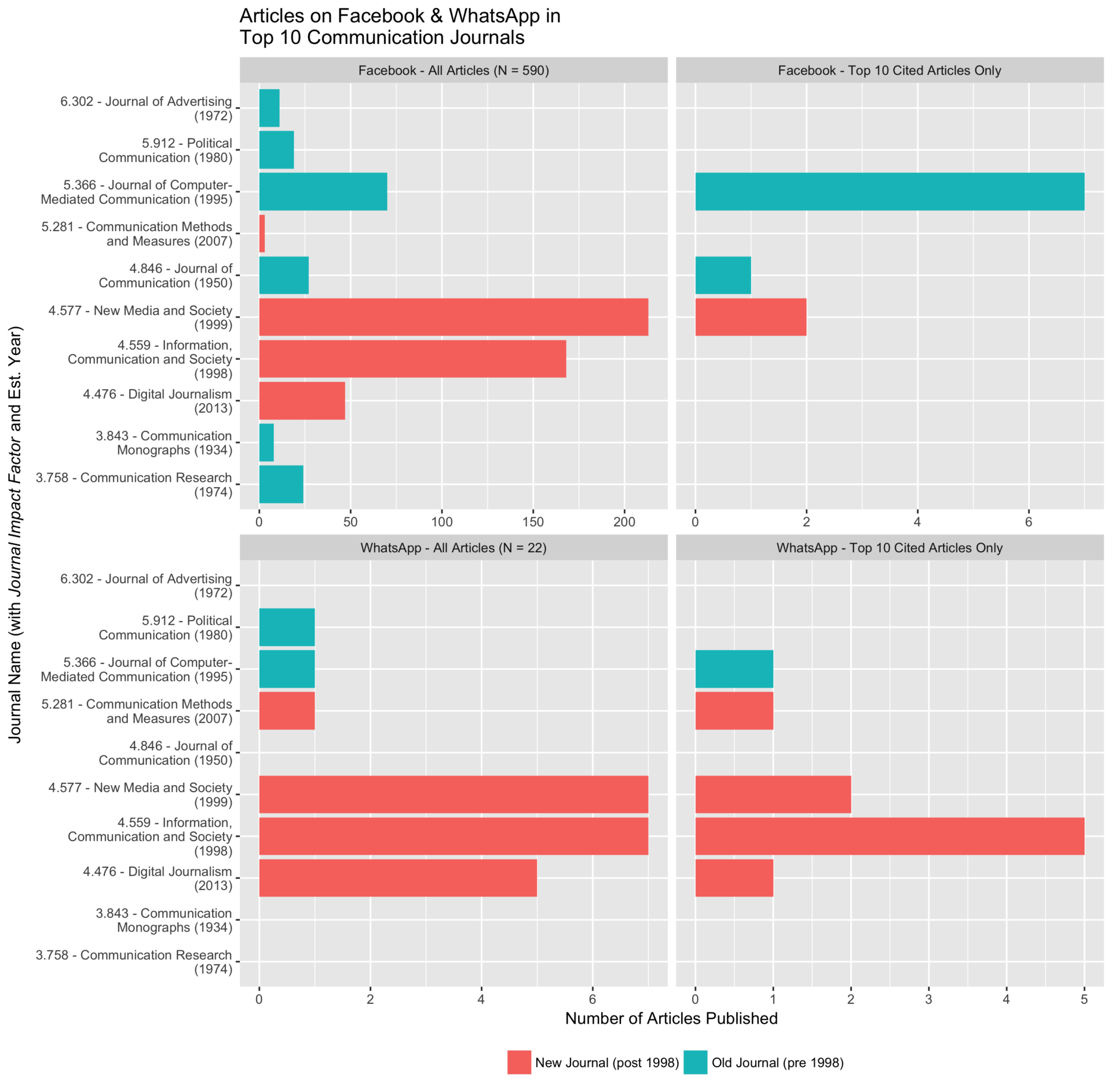

Finding 2: Agendas of published research on Facebook and WhatsApp.

A thematic meta-analysis of the research published in 10 communication journals with the highest Journal Impact Factors, shows that the research on Facebook and WhatsApp is limited (Fig. 2):

- Geographically: Out of 590 articles on Facebook, only 4 are on India, and none on Myanmar. This is despite the majority of Facebook users being in the Global South (and India), and despite the genocide in Myanmar – which has been shockingly understudied in comparison to the 2016 U.S. election. A mere 22 articles are on WhatsApp, which has 1.3 billion users located largely in the Global South.

- Theoretically: The highly cited articles are from journals with an administrative research orientation, notably the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. The three newer journals – New Media & Society; Information, Communication & Society; and Digital Journalism – however, provide room for non-administrative approaches to studying Facebook and WhatsApp. But overall – keeping with the discipline’s historical legacy – older journals generally adopt the administrative research tradition, and this research is cited the most.137 out of 10 of the most cited articles related to Facebook were from the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication.

More extensive reviews and meta-analysis studies of social media research in the past have also noted this geographical disparity as well as the dominance of administrative paradigm theories and methodologies (Caers et al., 2013; Kapoor et al., 2018; Ngai et al., 2015; Zhang & Leung, 2015). Crucially, these reviews and meta-analysis studies do not critique the administrative paradigm; their recommendations for “future directions” of research are almost always confined to the paradigm.

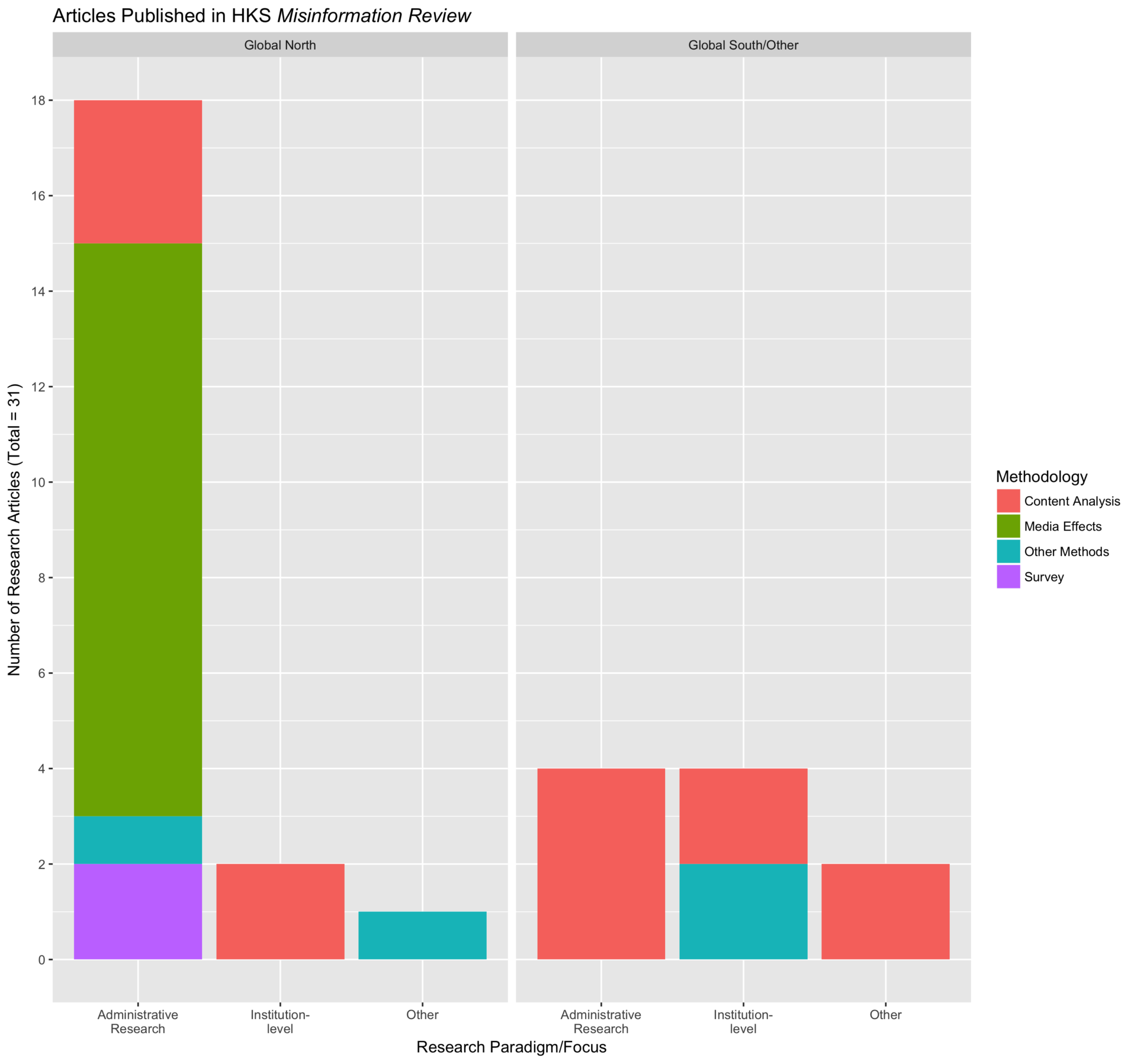

Finding 3: Agendas of published research in Misinformation Review (MR).

A thematic meta-analysis of all the research articles published in this journal, during its first year, shows similar patterns. MR’s first issue in January 2020 stated its goal as envisioning a response strategy to deal with misinformation and propaganda, and that “such a strategy requires interventions at many levels: legal, political, financial, infrastructural, cultural, and social” made possible by research on “all aspects of misinformation” (Pasquetto, 2020). However, the published research is limited (Fig. 3):

- Theoretically: Administrative paradigm research constitutes 71% of all articles. The focus is to understand audience behavior via media-effects experiments, surveys, and content analysis of people’s social media posts.

- Methodologically: The tools of administrative research – psychological studies, content analysis, and surveys – are the dominant method in MR. Even when scholars probe institutions, they mostly conduct content analysis of these institution’s postings on social media. Policy analysis, historical approaches, interviews, ethnographies, etc., are almost completely absent.

- Geographically: Only 19% of the articles are on the Global South.

Methods

(A) Agendas of research projects funded by Facebook-owned WhatsApp to study misinformation

On July 3, 2018, WhatsApp announced the “WhatsApp Research Awards for Social Science and Misinformation.” It announced the 20 winners on September 14, 2018. To assess the research orientation, a thematic meta-analysis was done using:

- Definitions of “high priority” areas obtained from the WhatsApp’s awards launch webpage.14See https://www.whatsapp.com/research/awards/. Internet Archive link of the same: https://web.archive.org/web/20180713090830/https://www.whatsapp.com/research/awards/

- The title, abstract, and the stated “high priority” category for the accepted proposals listed on the WhatsApp’s webpage.15See https://www.whatsapp.com/research/awards/announcement/. Internet Archive link of the same: https://web.archive.org/web/20190203020712/https://www.whatsapp.com/research/awards/announcement/

The research proposals were categorized by geography – Global North/South – based on the above information (see Appendix I).

(B) Agendas of published research on Facebook and WhatsApp

First, the list of the top 10 communication journals – by their Journal Impact Factor in 2019 – was obtained from Clarivate Analytics.16https://jcr.clarivate.com Second, under “advanced search” on Web of Science:17https://apps.webofknowledge.com/

- “Topic” was set to “Facebook,”

- “Publication name” to the aforementioned 10 journals,

- “Timespan” to 1900–2020,

- “Document type” to “article.”

- The above steps were repeated with “Topic” set to “WhatsApp.”

These search terms do not restrict results to the Global South or the topic to propaganda; the goal was to assess how these platforms are studied generally. The evidence presented is based on the thematic meta-analysis done with the 30 most-cited articles on Facebook, and all 22 articles on WhatsApp (see Appendix II for the list). Each journal’s featured and highly cited articles, as well as its “aims and scope,” informed the thematic meta-analysis.

(C) Agendas of published research in Misinformation Review (MR)

A thematic meta-analysis of all 31 peer-reviewed research articles published in MR during 2020 (excluding the article types “commentary” and “research note”) was done, focusing on these themes:

- Theory: Classified as “administrative research” when focused on understanding audiences, or “institution-level research” when focused on understanding institutional actors (state or non-state). This was determined based on the entirety of the article.

- Methodology: Classified as content analysis, media-effects experiment, or surveys based on methodology described in the article.

- Geography: Classified as Global North or Global South based on the research context or the study’s subjects.

See Appendix III for classifications.

Topics

Bibliography

Athique, A., & Parthasarathi, V. (Eds.). (2020). Platform capitalism in India (1st ed.; 2020 ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Avelar, D. (2019, October 30). WhatsApp fake news during Brazil election ‘favoured Bolsonaro.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/30/whatsapp-fake-news-brazil-election-favoured-jair-bolsonaro-analysis-suggests

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press.

Caers, R., De Feyter, T., De Couck, M., Stough, T., Vigna, C., & Du Bois, C. (2013). Facebook: A literature review. New Media & Society, 15(6), 982–1002. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813488061

Caplan, R., & boyd, d. (2018). Isomorphism through algorithms: Institutional dependencies in the case of Facebook. Big Data & Society, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951718757253

Creech, B. (2020). Fake news and the discursive construction of technology companies’ social power. Media, Culture & Society, 42(6), 952–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719899801

Fink, C. (2018). Dangerous speech, anti-Muslim violence, and Facebook in Myanmar. Journal of International Affairs, 71(1.5), 43–52. https://jia.sipa.columbia.edu/dangerous-speech-anti-muslim-violence-and-facebook-myanmar

Gary, B. (1996). Communication research, the Rockefeller Foundation, and mobilization for the war on words, 1938–1944. Journal of Communication, 46(3), 124–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1996.tb01493.x

Gary, B. (1999). The nervous liberals: Propaganda anxieties from World War I to the Cold War. Columbia University Press.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

Glander, T. (2000). Origins of mass communications research during the American Cold War: Educational effects and contemporary implications (1st ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gowen, A. (2018, July 4). As rumors fuel mob lynchings in India, WhatsApp offers $50,000 grants to curb fake news. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/as-rumors-fuel-mob-lynchings-in-india-whatsapp-offers-50000-grants-to-curb-fake-news/2018/07/04/93b098f7-edb2-44de-945e-81f59bf16e96_story.html

Hasebrink, U. (2012). The role of the audience within media governance: The neglected dimension of media literacy. Medijske Studije, 3(6), 58–73. https://hrcak.srce.hr/ojs/index.php/medijske-studije/article/view/6067

Hindman, M. (2009). The myth of digital democracy. Princeton University Press.

Horowitz, M. A., & Napoli, P. M. (2014). Diversity 2.0: A framework for audience participation in assessing media systems. Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture, 5(3), 309–326. https://doi.org/10.1386/iscc.5.3.309_1

The Indian Express. (2018, July 10). WhatsApp begins ad campaign, lists easy tips for users to fight fake news. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/technology/tech-news-technology/whatsapp-begins-ad-campaign-lists-easy-tips-for-users-to-fight-fake-news-5252903/

Indo-Asian News Service. (2018, September 5). WhatsApp starts second phase of radio ad campaign in India. NDTV Gadgets 360. https://gadgets.ndtv.com/apps/news/whatsapp-radio-ads-india-to-fight-misinformation-fake-news-1911699

Kapoor, K. K., Tamilmani, K., Rana, N. P., Patil, P., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Nerur, S. (2018). Advances in social media research: Past, present and future. Information Systems Frontiers, 20(3), 531–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-017-9810-y

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1941). Remarks on administrative and critical communications research. Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, 9(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.5840/zfs1941912

Mahaprashasta, A. A. (2020, August 3). How Delhi police turned anti-CAA WhatsApp group chats into riots “conspiracy.” The Wire. https://thewire.in/communalism/delhi-riots-police-activists-whatsapp-group

McChesney, R. W. (2015). Rich media, poor democracy: Communication politics in dubious times (new ed.). The New Press.

Miles, T. (2018, March 12). U.N. investigators cite Facebook role in Myanmar crisis. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rohingya-facebook-idUSKCN1GO2PN

Moyo, D., & Munoriyarwa, A. (2021). ‘Data must fall’: Mobile data pricing, regulatory paralysis and citizen action in South Africa. Information, Communication & Society, 24(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1864003

Mukherjee, R. (2019). Jio sparks Disruption 2.0: Infrastructural imaginaries and platform ecosystems in ‘Digital India.’ Media, Culture & Society, 41(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718818383

Murphy, L. W., & Cacace, M. (2020). Facebook’s civil rights audit – Final report. https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Civil-Rights-Audit-Final-Report.pdf

Muslim Advocates, & GPAHE. (2020). Complicit: The human cost of Facebook’s disregard for Muslim life. https://muslimadvocates.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Complicit-Report.pdf

Napoli, P. M. (2019). Social media and the public interest: Media regulation in the disinformation age. Columbia University Press.

Ngai, E. W. T., Tao, S. S. C., & Moon, K. K. L. (2015). Social media research: Theories, constructs, and conceptual frameworks. International Journal of Information Management, 35(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.09.004

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

Nothias, T. (2020). Access granted: Facebook’s free basics in Africa. Media, Culture & Society, 42(3), 329–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719890530

Parthasarathi, V., & Agarwal, S. (2020). Rein and laissez faire: The dual personality of media regulation in India. Digital Journalism, 8(6), 797–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1769493

Pasquetto, I. (2020). Volume 1, Issue 1 Editorial. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(1). https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/editorial-volume-1-issue-1/

Perrigo, B. (2019, January 25). How WhatsApp is fueling fake news ahead of India’s elections. Time. https://time.com/5512032/whatsapp-india-election-2019/

Perrigo, B. (2020, August 27). Facebook’s ties to India’s ruling party complicate its fight against hate speech. Time. https://time.com/5883993/india-facebook-hate-speech-bjp/

Pickard, V. (2019). Democracy without journalism?: Confronting the misinformation society. Oxford University Press.

Pooley, J. (2008). The new history of mass communication research. In D. W. Park & J. Pooley (Eds.), The history of media and communication research: Contested memories (pp. 43–70). Peter Lang.

Purnell, N., & Horwitz, J. (2020, August 14). Facebook’s hate-speech rules collide with Indian politics. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-hate-speech-india-politics-muslim-hindu-modi-zuckerberg-11597423346

Purohit, K. (2019, December 18). Post CAA, BJP-linked WhatsApp groups mount a campaign to foment communalism. The Wire. https://thewire.in/media/cab-bjp-whatsapp-groups-muslims

Rajkhowa, A. (2015). The spectre of censorship: Media regulation, political anxiety and public contestations in India (2011–2013). Media, Culture & Society, 37(6), 867–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443715584099

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2020). Breaking Harmony Square: A game that “inoculates” against political misinformation. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-47

Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., & Nygren, T. (2020). Prebunking interventions based on “inoculation” theory can reduce susceptibility to misinformation across cultures. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.37016//mr-2020-008

Sablosky, J. (2021). Dangerous organizations: Facebook’s content moderation decisions and ethnic visibility in Myanmar. Media, Culture & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720987751

Simpson, C. (1994). Science of coercion: Communication research and psychological warfare, 1945–1960. Oxford University Press.

Simpson, C. (Ed.). (1998). Universities and empire: Money and politics in the social sciences during the Cold War. The New Press.

Soundararajan, T., Kumar, A., Nair, P., & Greely, J. (2019). Facebook India: Towards the tipping point of violence: Caste and religious hate speech. Equality Labs.

Sproule, J. M. (1997). Propaganda and democracy: The American experience of media and mass persuasion. Cambridge University Press.

Vaidhyanathan, S. (2018). Antisocial media: How Facebook disconnects us and undermines democracy. Oxford University Press.

Wasserman, H. (2020). Fake news from Africa: Panics, politics and paradigms. Journalism, 21(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917746861

Zhang, Y., & Leung, L. (2015). A review of social networking service (SNS) research in communication journals from 2006 to 2011. New Media & Society, 17(7), 1007–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813520477

Funding

The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing Interests

No potential conflicts of interest.

Ethics

No institutional review board or ethics committee for human or animal experiments review was required.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZAFIEN, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SRGKQA, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LA2NLZ.