Peer Reviewed

News literacy education in a polarized political climate: How games can teach youth to spot misinformation

Article Metrics

33

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

We designed, implemented and evaluated a game about fake news to test its potential to enhance news literacy skills in educational settings. The game was largely effective at facilitating complex news literacy skills. When these skills were integrated into the design and fictional narrative of the game, diverse groups of students engaged with the learning goals and transferred this knowledge to real life contexts. The fictional narrative allowed students to learn about misinformation without the distraction of political stances and divisions, and deploying news literacy strategies as a winning strategy within the game allowed students to articulate and practice these skills. However, teacher preparation for game-based learning mattered, and additional support is needed for integrating such games into school curricula.

Research Questions

- To what extent can a fictional game about fake news teach youth to spot misinformation?

- What are the opportunities and challenges of using game-based approaches to facilitate youth news literacy?

Essay Summary

In this article we discuss the efficacy of LAMBOOZLED!, a card game—set in a fictional narrative environment—designed to teach middle and high school students strategies for identifying misinformation. We collected data from a)students who played the game in playtesting workshops (in the form of field notes, audio recordings, surveys, and youth-created artifacts), and b) educators who implemented the game in their classrooms (in the form of post-intervention interviews, across different grades and subject settings.) We found that the game was largely effective, in that:

- Students of diverse grade levels, academic subjects, and literacy levels were able to engage with the learning goals of the game and transfer news literacy strategies to real life contexts.

- The fictional narrative of the game allowed students to focus on deploying news literacy skills and engaging with misinformation without the distraction of contentious politics.

- Applying news literacy skills as a winning strategy within the game allowed students to articulate and practice these skills.

- From a practical perspective, the card game—designed for quick, multiple rounds—allowed for easy implementation across multiple classroom contexts, with varying class sizes and short instructional periods.

- Teachers’ preparation to integrate game-based learning into their overall curriculum was crucial, as teacher buy-in led to deeper and more effective student engagement. Additional support is needed for the curricular integration of games in general, and news literacy games in particular.

Implications

Given the need to cultivate youth news literacy skills in our age of misinformation (Chan et al, 2017; Robb, 2017; Roozenbeek et al, 2019; Stringer, 2018), and with current initiatives not fully addressing these needs (Bulger & Davison, 2018; Culver & Redmond, 2019; Kahne & Bowyer, 2017; Stringer, 2018), games can be an effective approach to foster news literacy skills (Admiraal, 2015; Basol et. al., 2020; Wilson, et. al., 2017). Games can seamlessly integrate content into their design, enabling the attainment of multiple types of learning goals at once (Molnar & Kostkova, 2013) and building competencies that can transfer to real-life situations (Gee, 2003). In the following, we discuss how particular game design elements were found to aid or constrain news literacy development, in the hope of informing the design, implementation and evaluation strategies of designers, educators and/or researchers interested in adopting game-based approaches to news literacy education, while also enriching the field of practice-based media literacy research.

LAMBOOZLED! is a news literacy card game where, in the tradition of deck-building games, players must put together the strongest “hands” of evidence surrounding particular news stories, in order to argue for the veracity (or lack thereof) of these stories and win the game. The game is played around three sets of cards: (1) the central news card, which contains content or formatting features which may point to the story being real or fake (e.g., a suspicious URL); (2) several central context cards, which determine external information that is available each round (e.g., a source’s social media profile, other news sources, etc.); and (3) the players’ hands, consisting of evidence cards (e.g. “The title sounds sensational”; “This is a satirical news site!”) and action cards with unique effects (e.g., stealing a card from another player’s hand). On each player’s turn, they may draw a new evidence or action card from the deck, play an action card, or, if they feel that their evidence is strong enough, present their set of evidence, forcing the other players to present theirs as well. The player with the strongest set of evidence according to point value wins the round—although if other players feel that the winner’s evidence isn’t applicable, they may challenge them to a debate (For more details, see lamboozled.com).

The game is designed for quick, multiple rounds of gameplay, suitable for both formal and informal learning contexts. The educational aims of the game included: (1) understanding bias and the need to use evidence in assessing it; (2) deploying declarative knowledge (e.g. by playing evidence cards that interrogate the superficial features of news articles, e.g., does the URL look suspicious?); and (3) deploying procedural knowledge (by playing evidence cards that cultivate procedural skills, like fact-checking or triangulation). Significantly, the game encourages players to use a mix of strategies—combining declarative and procedural knowledge—and to collect as much evidence as possible, as this increases their odds of playing a winning hand. To facilitate implementation in more formal contexts, we also developed lesson plans for educators that provide guidance on how to prepare and integrate the game into their classroom, as well as prompts to engage students in further discussion and learning after the gameplay. These materials also addressed the game’s alignment to relevant curricular standards.

LAMBOOZLED! proved tobe a robust news literacy resource for middle and high school students, when properly integrated into a learning environment. Specifically, we found that students could transfer in-game learning to real-world contexts, as iterative gameplay facilitated frequent deployment of skills and improved learning, and the fictional narrative of Green Meadows offered an engaging and safe non-political environment to learn about “fake news.” The game engaged diverse learners—across grade levels, academic subjects, and literacy levels—by breaking down existing social and learning barriers. Students who were typically quiet in regular class activities participated more in game-based learning, and were able to apply news literacy concepts to their own areas of interest. The latter is particularly important, as recent studies have identified youths’ perceived lack of relevance as a crucial challenge in news literacy education (CIRCLE, 2018; Media Insight Project, 2018; Robb, 2017).

Despite these positive takeaways, our research on LAMBOOZLED! found that the use of games within the context of news literacy education poses important challenges as well, especially in a more formal classroom context. In particular, the way in which educators framed, implemented, and facilitated the gameplay proved to be extremely significant, and subsequently influenced how their students engaged in the learning experience. Teachers who were well-prepared to implement the game in their classrooms, and who did so in alignment with their existing curriculum, reported better outcomes, in terms of both theirs and their students’ experience. In this sense, the readiness and acceptance of educators, facilitators, and subsequently students, is a key determinant of the effectiveness of game-based approaches to news literacy.

One important role educators or facilitators can play is to support students in applying and transferring the skills they learned in the game to real-world contexts. Although students tend to be more engaged and active with game-based learning (Squire, 2011)—which we certainly echoed in our findings—a transfer of conceptual skills may not occur automatically without teacher facilitation. The use of a fictional game narrative, while providing many benefits, can further complicate the transfer of skills. On the one hand, we found that relying on a fictional narrative provided opportunities for students to engage more deeply with the game and gain an understanding of complex news ecosystems while preempting politically-based conflict, tension or alienation along partisan lines; the latter is an especially important consideration, as youth polarization and politically motivated bullying are on the rise (see, e.g., Natanson, Cox, & Stein, 2020; Rogers, 2017). However, the suspension of disbelief required to engage in this fictional narrative can also lead to ambiguity regarding concepts of real and fake, and complicate both playability (i.e. the ease with which a game can be played), and the transfer of learning beyond the game.

Therefore, it is crucial that news literacy game initiatives include appropriate support to help students and educators make connections between what they are learning in the game, what they’ve learned in the classroom, and what they already know (Barzilai & Blau, 2014); this could take the form of auxiliary materials, like lesson plans, activities, modules/extensions or curated external information. These resources need to align with existing curricular goals, so that teachers can clearly see how games might fit into formal instruction and reflect their learning goals and standards, and how to prepare for the integration.

Findings

Reporting on student data first (i.e. playtesting observations, student surveys, reflection worksheets and student-created artifacts), and then teacher interviews, we illustrate our key findings below. Based on student data, we found that LAMBOOZLED! was effective in shaping student learning in three key ways. First, it enabled students to apply news literacy skills to real life situations; it was engaging as an instructional approach; and the fictional narrative of the game facilitated a depoliticized and fun learning experience, yet also sometimes complicated the contextual understanding of concepts of real or fake. Teacher interviews confirmed these findings, while also revealing the significance of educators’ prior preparation and fit into the curriculum.

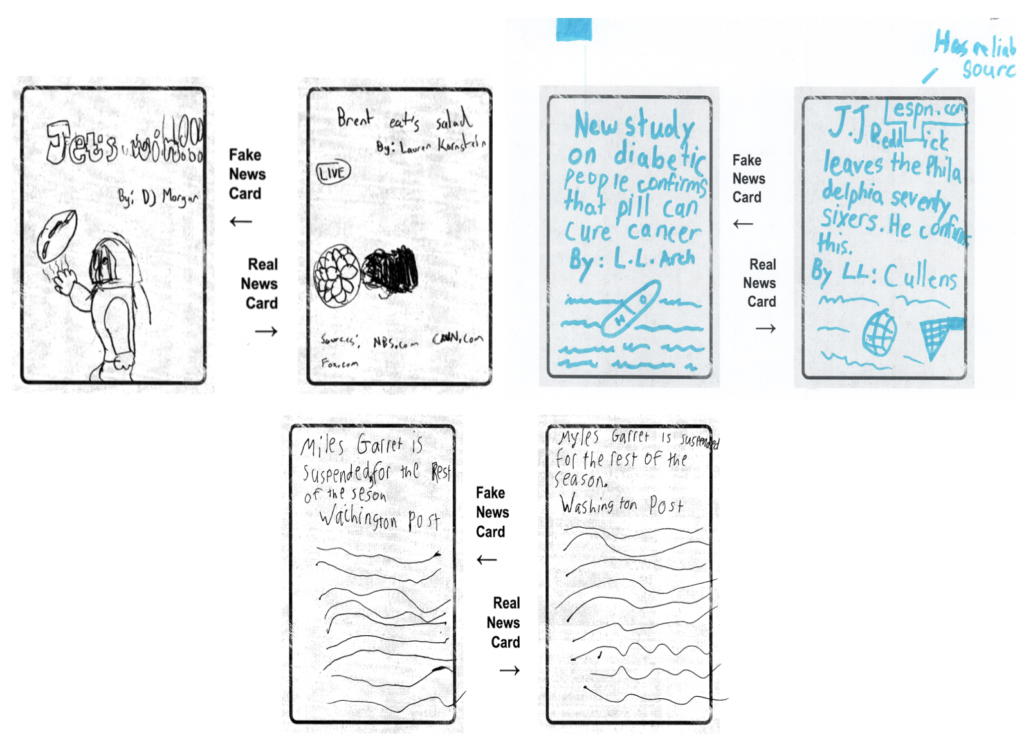

Based on multiple data sources from the student playtests, we found that students were able to deploy news literacy skills picked up in the game and understand how they may transfer to a real-world context. For instance, one 12th grade English student wrote in a post-game reflection worksheet that “[the cards] can help you check your sources to see if they are reliable because you know what to look for.” Similarly, other students described using the game cards as a “checklist” for news literacy skills. In playtesting sessions, after playing the game, students pulled out their digital devices to try out these strategies and check the veracity of current news headlines, while others discussed how they might apply them to content they see on their social media. For instance, demonstrating skills transfer in a post-game activity, some students applied the news literacy skills learned in the game to personally relevant news content like sports news (see Figure 1).

The analysis of student feedback surveys, as well as our observations during the playtests, revealed that the majority of students found the game valuable and engaging to play. In particular, during playtests, we observed that the fictional narrative of the game—which avoided the inclusion of real-life political actors or current news topics—proved engaging and avoided politically-charged conflict (which could be especially problematic in school settings). Many students noted on feedback forms that they enjoyed the sheep theme and had fun arguing over “real” vs “fake” evidence as part of the debate feature when evidence was challenged—although some students expressed they would have preferred the game to explicitly label a news article as either real or fake, as we discuss below.

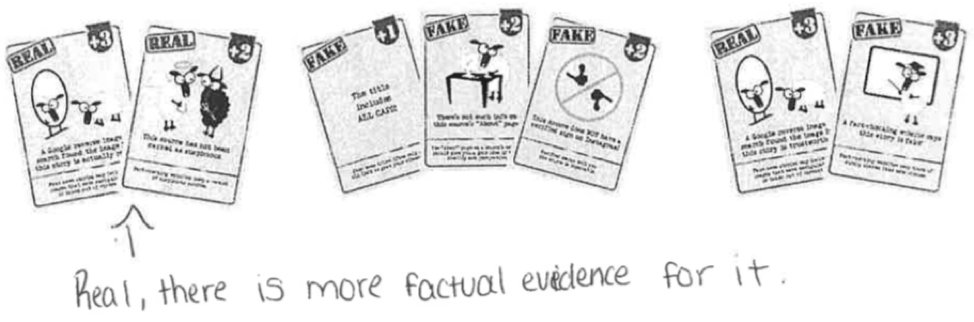

Despite increasing engagement and eliminating the potential distraction of real-life politics, the use of fictional news stories within the game also had its drawbacks. In particular, some students manifested confusion over the fact that there was no “absolute” fake or real news (as the game instructions noted, these are “sheep news, after all”, so in a sense, all news in the game are not real). In facilitating playtesting sessions, and also in analyzing the student reflection worksheets collected at the end of these sessions, we noticed that some students conflated “real” evidence with factual evidence and missed the more important takeaway that strong arguments can be made both for or against the veracity of a certain news story (see Figure 2).

Interviews with teachers after they implemented the game in their classroom confirmed the key findings derived from the student data (significantly, from teachers’ perspective as insiders to these classrooms, rather than the research team’s perspective as outsiders), while also shaping additional findings related to facilitation and classroom implementation, that could not have been captured in the playtesting sessions.

Specifically, teacher interviews confirmed our observation that students were engaged with the game and highly motivated to participate and learn. One of the social studies teachers shared that her 11th grade students were deeply engaged with the game, quoting a student who said, “I think this is the most fun we’ve had this year!” The educators included in our sample covered a wide array of subjects and grade levels, class size and duration, and most reported very high levels of engagement across contexts. Therefore, reading across the interviews, we conclude that a key benefit of this game-based approach to news literacy was its applicability to diverse populations of students. Educators were able to use the game effectively with students from grades 5 through 12, those who had special needs, and Multilingual Learners (or English Language Learners).

Teachers also observed that the fictional narrative of the game, in particular, increased student engagement and transfer. One teacher-librarian noted that she was initially skeptical of the fictional narrative, doubting that it would appeal to her older 11th and 12th grade students, but was proven wrong. She described in their interview, “I was like, oh, you know, they’re too cool for school. So I figured it’d be like, ‘What is this, these sheep, you know, some of the situations are kind of ridiculous.’ But they weren’t. They were into it.” Additionally, multiple teachers remarked in their interviews that the apolitical design of the game allowed for more personally meaningful instantiations of the content. As another 11th grade teacher – librarian described, “one student who is politically extremely conservative and doesn’t always speak up a lot… got really engaged in the conversation about the sources. So [the game] reached kids in a different way.”

Teacher interviews revealed that two key factors shaped the success of the game’s implementation in the classroom: teachers’ degree of preparation to do so and, respectively, their perception towards games as a learning tool. Both factors had an impact on student engagement with the game, as the teachers who reported positive outcomes also shared that they had prepared beforehand and had previous experience and/or enthusiasm about using games in their classrooms.

In terms of preparation, while the educators were provided with a lesson plan and additional resources to facilitate the gameplay, the way they ultimately prepared for introducing the game differed, ranging from no prior preparation to reading through the instructions and lesson plan, watching a video about the game, having students read the instructions as homework, or playing the game with their adult friends or family members. Teachers who saw prior preparation as a necessary component and factored that into their planning reported more success with the game and were more supportive of using it. One 11th and 12th grade special education teacher who played the game with adults prior to playing with her students reported in her interview that, “it’s easier for me to understand when I physically do something. I think that was helpful. I think it was just like, just getting a hang of it. So doing a few run-throughs prior to the kids.” The same teacher reported that her students were both engaged with the game and successful at learning news literacy skills by playing.

Conversely, some teachers did not prepare for the game and consequently found the game difficult; through teacher interviews and student feedback forms, this lack of prior preparation also influenced how their students interacted with and responded to the game. For instance, one 9th grade social studies teacher did not prepare their students to play the game in any way, saying, “I just gave [the game] to them. And I kind of said this is new. I want to see how it works. I gave them very little instruction.” This same teacher reported that their students had difficulty with the game: “after a while, I went back over to [the students] and I was like, ‘How’s it going?’ They’d actually put it away. And they were like, ‘We don’t get it. We couldn’t figure it out.’”

Additionally, teachers who integrated the game into their media literacy teaching rather than using it as a stand-alone lesson reported that their students were more engaged with the game, and enjoyed it more. However, a misalignment in the teacher’s perception of the game’s learning goals and their own curricular approach can lead to implementation challenges. While the game integrates both declarative and procedural skills related to news literacy, one 9th grade teacher-librarian tried to fit the game into her rather limited media literacy framework of “the ABCD method: author and authority, bias, content, and date.” Because the game did not align with these goals, the teacher found it challenging to facilitate. This, in turn, negatively influenced her students who thought that the game “wasn’t engaging or easy to follow.” Therefore, sufficient and appropriate support for the educators implementing the game is a key consideration that can maximize both the educational benefits and the engaging potential of such an approach.

Methods

Data was collected in the form of field notes and audio recordings from playtesting sessions with youth participants, as well as interviews with educators who implemented the game in their classrooms. The two approaches were complementary: our observation of youth engagement with the game in the playtesting sessions allowed us to closely examine the educational and social aspects of gameplay, while the educators’ reflections enabled us to develop a deeper understanding of how a game-based news literacy approach operates in authentic contexts of learning through different ways of facilitation.

In the playtesting workshops with students, the research team followed a facilitation guide developed to elicit student responses to the game, their deployment of declarative and procedural knowledge, and their more general attitudes towards (fake) news and games in small groups. One playtest was with two sixth-grade classes at an all-boys private school (N=48), while the other was with a group of high school students (grades 9-12) at a game design workshop (N=28). A variety of student artifacts were collected for analysis during these playtests, including a post-game survey, a reflection worksheet, and several multimodal artifacts. The post-game survey gave the research team insight into how well the students understood the game, while providing students the opportunity to give open feedback. The reflection worksheet (see Figure 2) encouraged students to deploy the learning goals in context and consider how they could apply these strategies outside the game; these reflections allowed the research team to gain insight into the procedural and declarative knowledge students used during the game. Last but not least, following gameplay, we provided students with a blank template and asked them to draw one real and one fake news card (see Figure 1). These multimodal artifacts allowed students to represent their ideas differently, and gave the research team the opportunity to analyze both images and text as they related to the learning goals.

In the case of teacher interviews, we interviewed the educators (N=11) after they implemented the game in their respective contexts of teaching (11 classrooms, with a total of 241 students). Educators were recruited via the research team’s networks of teachers, educators and administrators; the recruitment message specified that we are seeking feedback on a media literacy game in development. When interested participants responded to this call and signed our IRB-approved consent forms, we mailed them the physical games (along with a lesson plan, instructions and a tutorial video) and then followed up to schedule remote interviews, as the educators were geographically located all over the United States. Our call generated significant interest; in selecting educators to be interviewed, we aimed for a diversity of subjects and grade levels, in order to understand how (and whether) the game works in each of these contexts, and what kind of support different teachers might need. Therefore, there was a wide variety of subjects represented, ranging from English and Library Sciences to Social Studies and AP US Government courses. Their students ranged from grades 5 through 12. Teachers implemented this game in either one or two class sessions, so the intervention ranged from 45 minutes to 90 minutes, and were free to integrate it within their curricula as they saw fit, in order to shed light on realistic contexts of implementation. The post-intervention interview included questions about their backgrounds and classroom dynamics, how they went about preparing and implementing the game, and their takeaways and recommendations. These teacher perspectives were extremely valuable in our analysis, as their ability to effectively facilitate the game within their respective learning context was highly significant to our assessment of the game, as well as identification of opportunities and challenges from a variety of perspectives.

All data—i.e. transcribed teacher interviews, field notes and audio recordings from playtesting workshops, and student-created artifacts—were analyzed by the research team. In doing so, the team was aided by a general coding rubric that foregrounded the a) deployment of the learning goals (declarative and procedural knowledge), b) game playability, and c) implications game-based news literacy education more broadly. Since we were working with multiple data sources that were very different from one another, the coding rubric aimed to help the research team label evidence so that these various data sources could be combined and put into conversation with each other. After discussing the coding categories, each member of the research team independently coded sections of the data. The emerging themes from the codes were then coalesced into higher-level observations, in line with our research questions. In outlining these findings above, we integrate evidence from multiple data sources and bring in both youth and educator perspectives to facilitate a fuller understanding of these dynamics.

Bibliography

Admiraal, W. (2015). A role-play game to facilitate the development of students’ reflective Internet skills. Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 301-308.

Barzilai, S., & Blau, I. (2014). Scaffolding game-based learning: Impact on learning achievements, perceived learning, and game experiences. Computers & Education, 70, 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.08.003

Basol, M., Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2020). Good news about bad news: Gamified inoculation boosts confidence and cognitive immunity against fake news. Journal of Cognition, 3(1), 1-9.

Bulger, M., & Davison, P. (2018). The promises, challenges, and futures of media literacy. Data & Society Institute. Retrieved from: https://datasociety.net/output/the-promises-challenges-and-futures-of-media-literacy/

Chan, M. P. S., Jones, C. R., Hall Jamieson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2017). Debunking: A meta-analysis of the psychological efficacy of messages countering misinformation. Psychological science, 28(11), 1531-1546.

CIRCLE. (2018). Fall youth survey. Medford, MA: The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.

Culver, S. H. & Redmond, T. (2019). Media literacy snapshot. National Association for Media Literacy Education. Retrieved from https://namle.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/SOML_FINAL.pdf

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Computers in Entertainment (CIE), 1(1), 20-20.

Kahne, J., & Bowyer, B. (2017). Educating for democracy in a partisan age: Confronting the challenges of motivated reasoning and misinformation. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1), 3-34.

Media Insight Project (2018). How younger and older Americans understand and interact with news. American Press Institute. Retrieved from https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/publications/reports/survey-research/ages-understand-news

Molnar, A., & Kostkova, P. (2013, July). On effective integration of educational content in serious games: Text vs. game mechanics. In 2013 IEEE 13th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (pp. 299-303). IEEE.

Natanson, H., Cox, J.W., & Stein, P. (2020, Feb. 13). Trump’s words, bullied kids, scarred schools. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/local/school-bullying-trump-words/

Robb, M.B. (2017) News and America’s kids: How young people perceive and are impacted by the news. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media.

Rogers, J. (2017). Teaching and learning in the age of Trump: Increasing stress and hostility in America’s high schools. UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access. Retrieved from https://idea.gseis.ucla.edu/publications/teaching-and-learning-in-age-of-trump

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2019). Fake news game confers psychological resistance against online misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5(1), 1-10.

Squire, K. (2011). Video games and learning: Teaching and participatory culture in the digital age. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Stringer, K. (2018, March 12). Push for media literacy takes on urgency amid rise of ‘fake news’. Education Writers Association. Retrieved from https://www.ewa.org/blog-educated-reporter/push-media-literacy-takes-urgency-amid-rise-fake-news?utm_source=the74&utm_medium=linkback&utm_campaign=74-hosted

Wilson, S. N., Engler, C. E., Black, J. E., Yager-Elorriaga, D. K., Thompson, W. M., McConnell, A., Cecena, J.E., Ralston, R., & Terry, R. A. (2017). Game-based learning and information literacy: A randomized controlled trial to determine the efficacy of two information literacy learning experiences. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 7(4), 1-21.

Funding

The research was supported by the Teachers College Provost Investment Fund.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethics

The research protocol was approved by the Teachers College Institutional Review Board (IRB). All participants provided informed consent.

Copyright

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

NA