Peer Reviewed

Information control on YouTube during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

Article Metrics

0

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

This research note investigates the aftermath of YouTube’s global ban on Russian state-affiliated media channels in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Using over 12 million YouTube comments across 40 Russian-language channels, we analyzed the effectiveness of the ban and the shifts in user activity before and after the platform’s intervention. We found that YouTube, in accordance with its promise, effectively removed user activity across the banned channels. However, the ban did not prevent users from seeking out ideologically similar content on other channels and, in turn, increased user engagement on otherwise less visible pro-Kremlin channels.

Research Questions

- How effective was YouTube’s global ban on Russian state-affiliated channels in reducing (commenting) activity on these channels?

- To what extent did users previously active on banned channels redirect their engagement to other types of political content on YouTube?

Essay Summary

- We collected over 12 million comments across a range of pro- and anti-Kremlin Russian-language YouTube channels during Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

- The analysis focuses on YouTube’s global ban on several Kremlin-affiliated YouTube channels and the subsequent changes in commenting activity.

- Comment activity on banned channels dropped sharply to near zero immediately after the ban, indicating that the ban was, in fact, successful in preventing exposure to these channels.

- Users previously engaging with banned channels substantially increased engagement on other (non-blocked) pro-Kremlin channels in the weeks following the ban.

- This suggests a potential “substitution effect” either through users actively seeking out alternative outlets in the wake of the ban or through YouTube’s algorithmic recommendations.

- These findings have important implications for our understanding of information control as a means of suppressing disinformation sources. Global bans can prevent users from accessing certain content. However, we also show the challenges of such policies by empirically illustrating how the bans can redirect at least some of the online engagement toward ideologically similar alternatives.

Implications

The war between Russia and Ukraine takes place on physical battlefields as well as in the information space. This became apparent during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014 and continues to be relevant during the recent invasion on February 24, 2022. Since the beginning of the ongoing war, numerous scholars across various fields have noted that the so-called “information war” plays an important political and military role (Darczewska, 2014; Thornton, 2015). While the scholarly community, as well as the general public, has largely focused on the production and dissemination of content, an important part of the informational struggle also takes place through information control, both in Russia, Ukraine, and even the EU (European Commission, 2022; Golovchenko, 2022).

This research note focuses on online user activity on YouTube, one of the world’s most popular social media platforms. YouTube, among other large social media platforms, has long been criticized for allowing hate speech and disinformation to foster without much action. These concerns intensified on the heels of Russia’s military aggression and crackdowns on independent media (Milmo, 2022). Simultaneously, YouTube also plays a valuable role in disseminating information and regime-critical opinions in autocracies like Russia (Gainous et al., 2018; Reuter & Szakonyi, 2015). YouTube’s double-edged sword nature makes it an important platform in the struggle for “truth” about the war.

Pro-Kremlin disinformation about the war in Ukraine and the Kremlin’s strategic information control have also been met with great concern in the West. Russian state-controlled media, such as Sputnik and RT (formerly Russia Today), are widely recognized among researchers, fact-checkers, and the broader public as active perpetrators in the dissemination of disinformation (for an overview of the websites’ reach, see Kling et al., 2022) (BBC, 2019; Elliot, 2019; Golovchenko, 2020; Thornton, 2015). On March 2, 2022, the European Union responded by banning access to these channels to limit “the Kremlin’s disinformation and information manipulation assets” (European Commission, 2022). On March 11, YouTube took a further step by announcing a block of Russian state media as a whole across the platform, based on its policy against content that “denies, minimizes or trivializes well-documented violent events” (Reuters, 2022). This global ban is the focus of our research note.

Using publicly available data from YouTube’s API, this research note assesses the effectiveness and implications of YouTube’s ban in reducing engagement with Russian state-affiliated media. We restricted our analysis to Russian-language YouTube channels, as these target not only domestic audiences but also Russian speakers abroad, including the Russian diaspora and large Russian-speaking populations in several post-Soviet states (Cheskin & Kachuyevski, 2018). Prior research has demonstrated that state-owned Russian-language media contributed to polarization during parliamentary elections in Ukraine, underscoring the scope of Russian-language political content disseminated by Kremlin-affiliated outlets (Rozenas & Pesakhin, 2018).

We operationalize engagement as the number of comments for each video (for a discussion of the relation between comments and engagement, see Byun et al., 2023). Commenting serves as an important proxy for online activity because a high comment count also implies a high number of views. However, engagement through comments is also an important resource in its own right that can be used to gain even more visibility. While YouTube does not disclose the details of its algorithm, the platform has indicated that video visibility—for example, in search results—is also influenced by engagement (YouTube, n.d.). Our results suggest that YouTube’s ban against Russian state media almost eliminated online engagement with their videos. However, we also observed a sudden and discontinuous increase in commenting engagement on non-banned pro-Kremlin channels. We corroborated this further by showing that users who were active on blocked pro-Kremlin channels before the ban responded to the policy by increasing their activity on these non-blocked pro-Kremlin channels. The findings have two important implications.

Firstly, we can confirm independently that YouTube did follow through with its effort to limit Russian disinformation. While there is a debate in the literature on the effectiveness of information control policies (Gläßel & Paula, 2020; Gohdes, 2020; Hobbs & Roberts, 2018; Jansen & Martin, 2015; Roberts, 2020; Shadmehr & Bernhardt, 2015), our findings partly support that such policies can limit “undesirable” information (Chen & Yang, 2019; King et al., 2013; Stockmann, 2013; Stern & Hassid, 2012). This is also in line with Santos Okholm et al. (2024), who found that the geo-blocking of the Russian RT and Sputnik within the EU’s territory added friction and reduced the sharing of these outlets on Facebook.

Secondly, the findings also highlight the limits of online bans as a means of fighting disinformation. We show empirically that some of the activity may have moved to channels known for spreading disinformation about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The sudden increase in commenting engagement among non-blocked pro-Kremlin channels supports the notion of a “substitution effect,” a pattern where at least some of the engagement from the blocked channels shifted to non-banned parts of the pro-Kremlin media ecology on YouTube. This could be driven either by users’ direct effort to search for non-blocked alternatives that may offer similar content or indirectly by YouTube’s suggestion algorithms that introduce new pro-Kremlin content to users based on their viewing history. Substitution of banned or blocked information has previously been documented across different contexts, including in authoritarian regimes’ moderation of online communities and deplatforming studies investigating migration to alternative platforms (Buntain et al., 2023; Chandrasekharan et al., 2017; Horta Ribeiro et al., 2023; Roberts, 2018; Rogers, 2020). This research note focuses on within-platform migration and substitution of content. While it is not possible to isolate the main mechanism behind this within the scope of this study, our findings emphasize the challenges of online bans. While the initial bans can be effective, they may not be sufficient to fully curb disinformation efforts on a broader scale.

It is outside of the scope of this research note to estimate the final net effect of the ban on the pro-Kremlin environment on YouTube as a whole. Theoretically, one can expect that a portion of the audience of the banned channels did not find their way to the non-banned alternatives. In this case, the online activity for pro-Kremlin YouTube content would be reduced overall. It is therefore likely that the ban succeeded in disrupting the pro-Kremlin YouTube media environment, despite the substitution effect captured in this research note. We encourage future research to empirically test whether this is the case. Additionally, further research is encouraged to investigate whether the ban prompted pro-Kremlin audiences to migrate to other platforms in search of the banned pro-Kremlin content.

Furthermore, the findings are limited to engagement through non-deleted comments; it does not reveal to what extent an immediate decline in viewership followed the YouTube ban. The latter was not possible because the data was collected after the ban, and YouTube’s API only provided access to the latest view count rather than historical changes. The exact date or nature of the ban was not publicly announced by YouTube in advance, to the best of our knowledge. The advantage of commenting data is that each individual comment is time-stamped, enabling post-hoc historical studies of bans. The analysis does not geolocate the commenting activity for both pragmatic and ethical reasons. It is possible that the commenting activity on Russian state media channels declined mainly among Russian-speaking audiences outside the Russian Federation but only to a lesser degree within the country, or vice versa.

Despite these limitations, our findings serve as a reminder that similar social media policies should not view state-affiliated channels in isolation but instead consider them as part of a broader ecology that promotes similar propaganda and disinformation narratives, regardless of the actual funding or formal state affiliation. Going beyond the case of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is theoretically possible that bans in other contexts could redirect engagement to non-banned substitutes that are even more prone to spreading disinformation. If policymakers or social media firms choose to combat disinformation through similar bans, it is important that such measures are sufficiently broad in scope from the outset and also encompass more fringe sources, in order to minimize the risk of users substituting harmful content with even more extreme versions of the blocked sources. Perhaps more importantly, one should always consider the additional risk of harmful substitution when making the decision. Perhaps more importantly, one should always consider the additional risk of harmful substitution when making such decisions. This requires not only empirical analysis but also, ideally, data access for independent analysts who can critically examine both the intended and unintended consequences of these interventions. Additionally, this study is agnostic on the appropriateness of removing social media content based on accuracy assessments; rather, we are interested in focusing on the effects of doing so.

Findings

Finding 1: YouTube’s ban on Russian state-affiliated media successfully reduced activity on the blocked channels.

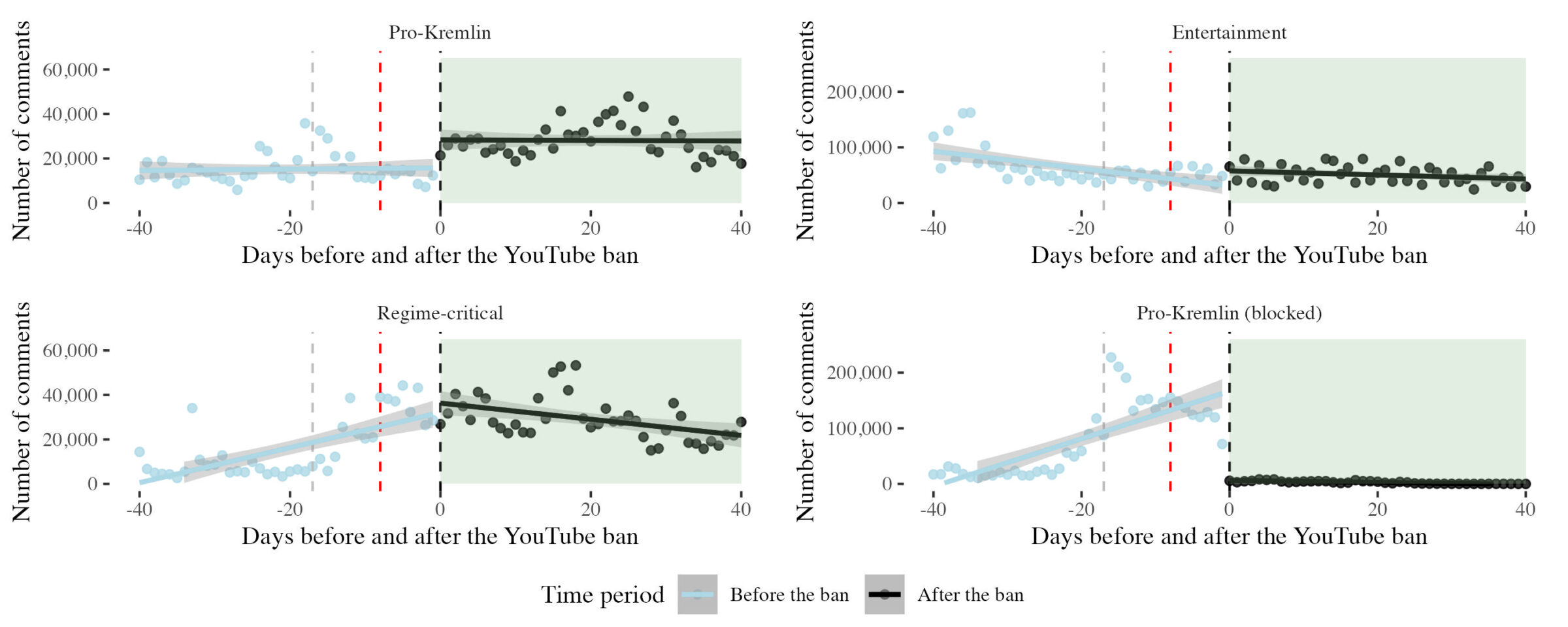

First, we examined the effects of YouTube’s ban on Russian state-affiliated media. Figure 1 shows the change in the daily number of comments on the videos from the respective channels. We demonstrated activity among regime-critical outlets, as well as the relatively apolitical Russian-speaking entertainment channels, as a baseline. There was a sharp and strong decline in comment engagement for Russian state-affiliated media (bottom left) on the day after YouTube announced its global ban policy. This includes a decline in major, mainstream Kremlin-affiliated media outlets like Rossiya 24 and relatively popular yet more niche outlets like the ultra-conservative Tsargrad and Zvezda, run by the Russian Ministry of Defense (see Appendix B for the complete list of channels). In contrast, we observe no sharp and discontinuous drop in other channels. The latter supports the interpretation that the drastic decline was likely the result of YouTube’s targeted ban rather than a broader decline in the Russian-speaking YouTube environment.

Looking at the trends in commenting activity within the 40 days prior to the ban, Figure 1 shows a notable increase at the onset of the full-scale invasion, peaking at 250,000 daily comments. This is followed by a slight drop in commenting activity coinciding with the implementation of heightened censorship measures, before comments level out.1A further deep dive into the potential implication of the censorship laws implemented during this time is outside the scope of this paper but is addressed in a separate working paper being finalized by the authors of this research note. Comparing the commenting activity among blocked channels in the 10 days preceding the ban and the first 10 days after the ban (March 12–22), the daily number of comments drops from 12,517 to 23. While commenting activity drops down to 0.18% for the blocked pro-Kremlin channels, it does not disappear completely. A few comments were made on the blocked channels during the period after the ban. Appendix C shows an overview of the post-ban activity of the blocked channels. A deeper investigation of why this activity continued is outside the scope of this Research Note. However, it is an important factor to keep in mind, as this could indicate that the ban was not fully implemented everywhere (at least not at once). Nevertheless, the findings indicate that engagement among the banned pro-Kremlin channels was severely reduced following the ban.

These findings confirm that YouTube successfully limited the online activity tied to the Russian state-affiliated channels in the sample. Arguably, these are also the most influential Kremlin-affiliated channels. Therefore, while we cannot comment on the effectiveness of the ban on channels outside of this sample, we can reaffirm that the ban did halt the activity on some of the largest spreaders of state-sponsored pro-Kremlin content.

Finding 2: YouTube’s global ban was potentially accompanied by a “substitution effect” where some commenting engagement from the blocked pro-Kremlin channels moved to other non-blocked pro-Kremlin channels.

Our findings suggest that YouTube’s ban on the major pro-Kremlin channels likely increased commenting engagement for other pro-Kremlin channels. As shown in Figure 1, the increase is sudden and sharp around the cut-off date (March 12). The daily engagement with the channels almost doubles after the ban compared to before: Increasing from 1,199 during the period before the invasion (Jan 31–Feb 10) to 2,513 during the first ten days after the ban.

In contrast, although we observe a slight increase in commenting activity among regime-critical channels, there is little indication that this is caused by the ban. Unlike the jump for the non-banned pro-Kremlin channels, the change appears to occur days before the ban.

The sudden increase among non-blocked pro-Kremlin outlets suggests that some users commonly engaging with Kremlin-associated channels have migrated to non-blocked pro-Kremlin alternatives. As mentioned earlier, this pattern aligns with a “substitution effect,” where users either directly search for replacement channels that still disseminate pro-Kremlin disinformation or are indirectly nudged to these sources by social media algorithms.

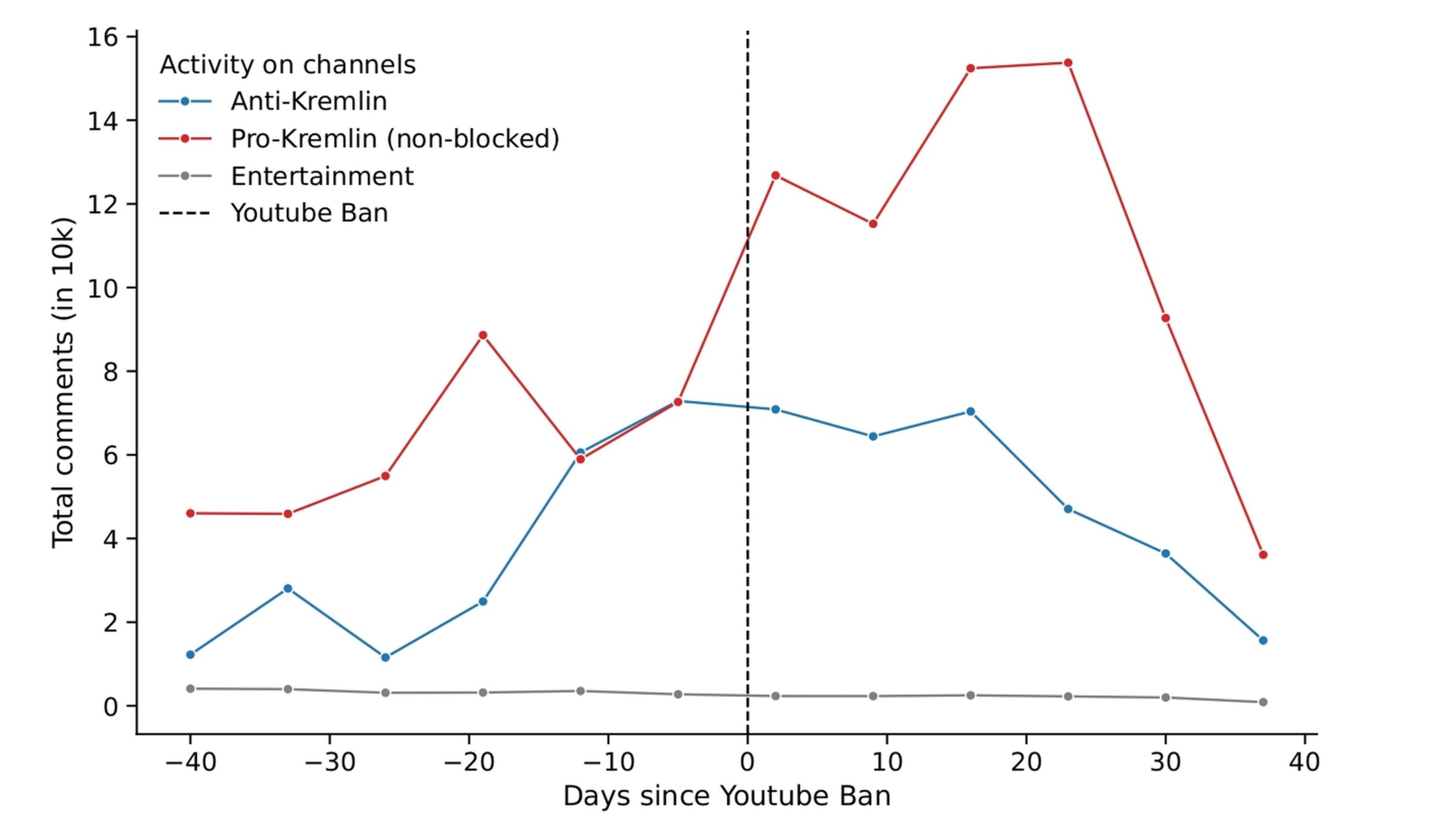

To further corroborate this pattern, we examine the activity of users who have posted at least one comment on the blocked Pro-Kremlin channels before the ban within the examined period. As shown in Figure 2, the number of comments by these users more than doubled on non-blocked pro-Kremlin channels. While they also become slightly more active on regime-critical channels, there is a much larger influx of comments on pro-Kremlin channels where daily comment engagement nearly doubles and appears to be driven by users migrating from the blocked channels. It is worth noting, however, that the commenting activity on both non-blocked pro-Kremlin channels and regime-critical anti-Kremlin channels declines approximately 2–3 weeks after the ban. The drop is likely driven by a reduction in video uploads in the data set (see Figure D3 in the Appendix).

Methods

Data

The data consists of 12,315,588 YouTube comments tied to 13,950 videos from 40 channels in the 40 days preceding and following March 12, 2022, the day YouTube fully implemented its ban on Russian state media globally. YouTube announced the ban on March 11. Although we do not know precisely when YouTube intended to enforce the ban, we treated the following day (March 12) as the day of implementation for pragmatic reasons. We restricted the sample to Russian-language channels; accordingly, we operated on the assumption that those engaging with the channel content were also predominantly Russian speakers.

The data was collected in late spring 2022 (after the ban was put in place) using the following procedures. First, we identified 10 pro-Kremlin media outlets banned by YouTube,2There is one exception in our data: The channel Tsargrad (царьград-тв) was blocked in July of 2020 for breaking YouTube guidelines, meaning that the block of this channel had no connection to the invasion in 2022. 10 non-banned pro-Kremlin channels, and 10 regime-critical channels. The selection followed systematic inclusion criteria (subscriber counts above 100,000, Russian-language audience content, and established reputations for pro-Kremlin or regime-critical content; see Appendix A for details). We additionally included the 10 most popular entertainment channels in Russia, based on whatstat.ru and br-analytics.ru, as a non-political baseline. It should also be noted that at the time of data collection, the content of the banned channels was no longer accessible through YouTube’s front end. However, their channel front pages (i.e., youtube.com/@username) and associated metadata were still retrievable via the YouTube Data API. We identified the relevant channel user IDs through manual searches and, in turn, collected video and comment metadata from the blocked channels. This information was available during our data collection period but has since become inaccessible through the API.

In the second step, we used the YouTube API to collect historic metadata from all channels, which included the video IDs and posting time of all videos uploaded by the 40 channels between January 24 and April 24. We then used the video metadata to collect all the public comment data on these videos, including the comment text, author IDs, and comment timestamps.3The analysis of comment content is outside the scope of this research note; however, the authors address this in a separate working paper. The data collection took place from April 6 to May 25, 2022, and the full list of channels is available in Appendix B. The data only includes comments that had not been deleted at the time of data collection. It should be noted that YouTube’s own moderation mechanisms may already have removed some comments prior to collection, which could affect the completeness of the dataset. This does present a considerable limitation to our analysis, as the drop in comments observed in the initial days following the ban could have been driven by this. While this impacts our interpretation of the ban’s timing and immediate effectiveness, it was unlikely to impact the findings related to channel migration by commentators.

Investigating change in time

Our analysis of commenting activity is descriptive. For our investigation of the effectiveness of YouTube’s own ban, we focused on the comprehensive global ban implemented after March 11. The exact time of the ban, however, was unknown to the public. The sudden decrease to near-zero in activity on banned pro-Kremlin channels right after the exogenous ban does warrant a causal interpretation. However, we do not attempt to estimate or claim any causal effects regarding the potential “substitution” or movement to non-banned channels. In this setting, we visualize the commenting activity using a disrupted time series setup, allowing for different slopes before and after the implementation of the ban. To get a comprehensive overview of the development in commenting activity across channel types, the number of comments is grouped by the day each comment was posted and channel type—i.e., regime-critical, pro-Kremlin (banned and non-banned), and entertainment.

Topics

Bibliography

BBC. (2019). Russia’s RT banned from UK media freedom conference. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-48919085

Chen, Y., & Yang, D. Y. (2019). The impact of media censorship: 1984 or Brave New World? American Economic Review, 109(6), 2294–2332. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20171765

Buntain, C., Innes, M., Mitts, T., & Shapiro, J. (2023). Cross-platform reactions to the post-January 6 deplatforming. Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media, 3. https://doi.org/10.51685/jqd.2023.004

Byun, U., Jang, M., & Baek, H. (2023). The effect of YouTube comment interaction on video engagement: Focusing on interactivity centralization and creators’ interactivity. Online Information Review, 47(6), 1083–1097. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-04-2022-0217

Chandrasekharan, E., Pavalanathan, U., Srinivasan, A., Glynn, A., Eisenstein, J., & Gilbert, E. (2017). You can’t stay here: The efficacy of Reddit’s 2015 ban examined through hate speech. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 1(CSCW), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3134666

Cheskin, A., & Kachuyevski, A. (2018). The Russian-speaking populations in the post-Soviet space: Language, politics and identity. Europe-Asia Studies, 71(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2018.1529467

Darczewska, J. (2014). The anatomy of Russian information warfare: The Crimean operation, a case study. Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia [Centre for Eastern Studies]. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/point-view/2014-05-22/anatomy-russian-information-warfare-crimean-operation-a-case-study

Elliot, R. (2019, July 26). How Russia spreads disinformation via RT is more nuanced than we realise. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jul/26/russia-disinformation-rt-nuanced-online-ofcom-fine

European Commission. (2022). Ukraine: Sanctions on Kremlin-backed outlets Russia Today and Sputnik [Press release]. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_1490?s=09

YouTube. (n.d.) Recommendations. https://www.youtube.com/intl/en_be/howyoutubeworks/recommendations/

Gainous, J., Wagner, K. M., & Ziegler, C. E. (2018). Digital media and political opposition in authoritarian systems: Russia’s 2011 and 2016 Duma elections. Democratization, 25(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2017.1315566

Gläßel, C., & Paula, K. (2020). Sometimes less is more: Censorship, news falsification, and disapproval in 1989 East Germany. American Journal of Political Science, 64(3), 682–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12501

Gohdes, A. R. (2020). Repression technology: Internet accessibility and state violence. American Journal of Political Science, 64(3), 488–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12509

Golovchenko, Y. (2020). Measuring the scope of pro-Kremlin disinformation on Twitter. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), Article 176. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00659-9

Golovchenko, Y. (2022). Fighting propaganda with censorship: A study of the Ukrainian ban on Russian social media. The Journal of Politics 84(2), 639–654. https://doi.org/10.1086/716949

Horta Ribeiro, M., Hosseinmardi, H., West, R., & Watts, D. J. (2023). Deplatforming did not decrease Parler users’ activity on fringe social media. PNAS Nexus, 2(3), Article pgad035. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad035

Hobbs, W. R., & Roberts, M. E. (2018). How sudden censorship can increase access to information. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 621–636. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000084

Jansen, S. C., & Martin, B. (2015). The Streisand effect and censorship backfire. International Journal of Communication, 9. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2498

King, G., Pan, J., & Roberts, M. E. (2013). How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression. American Political Science Review, 107(2), 326–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000014

Kling, J., Toepfl, F., Thurman, N., & Fletcher, R. (2022). Mapping the website and mobile-app audiences of Russia’s foreign communication outlets, RT and Sputnik, across 21 countries. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 3(6). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-110

Milmo, D. (2022, January 12). YouTube is a major conduit of fake news, fact-checkers say. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/jan/12/youtube-is-major-conduit-of-fake-news-factcheckers-say

Reuter, O. J., & Szakonyi, D. (2015). Online social media and political awareness in authoritarian regimes. British Journal of Political Science, 45(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000203

Reuters. (2022, November 3). YouTube announces an immediate block on Russian state-funded media channels globally. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/next/2022/03/11/youtube-announces-an-immediate-block-on-russian-state-funded-media-channels-globally

Roberts, M. (2018). Censored: Distraction and diversion inside China’s Great Firewall. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77b21

Roberts, M. E. (2020). Resilience to online censorship. Annual Review of Political Science, 23(1), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-032837

Santos Okholm, C., Fard, A. E., & ten Thij, M. (2024). Blocking the information war? Testing the effectiveness of the EU’s censorship of Russian state propaganda among the fringe communities of Western Europe. Internet Policy Review, 13(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.14763/2024.3.1788

Rogers, R. (2020). Deplatforming: Following extreme internet celebrities to Telegram and alternative social media. European Journal of Communication, 35(3), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120922066

Rozenas, A., & Pesakhin, L. (2018). Electoral effects of biased media: Russian television in Ukraine. American Journal of Political Science, 64(3), 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12355

Shadmehr, M., & Bernhardt, D. (2015). State censorship. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 7(2), 280–307. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.20130221

Stern, R. E., & Hassid, J. (2012). Amplifying silence: Uncertainty and control parables in contemporary China. Comparative Political Studies, 45(10), 1230–1254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011434295

Stockmann, D. (2013). Media commercialization and authoritarian rule in China. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139087742

Thornton, R. (2015). The changing nature of modern warfare: Responding to Russian information warfare. RUSI Journal, 160(4), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2015.1079047

Funding

This research is supported by the Copenhagen Center for Social Data Science and the Department of Political Science at the University of Copenhagen through the fund for “Urgent Computational/Digital Social Science Research on the Ukraine War.”

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The study uses publicly available data provided by YouTube through its API. An IRB review was not applicable, and obtaining consent from online users was not possible. The manuscript does not disclose any personal information about the commenting users; only aggregated results for the named media channels are included. The replication data include aggregated measures—such as the number of comments per day—rather than the raw data downloaded through the API. This approach was taken to comply with YouTube’s terms of service.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/JAC6BY

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants at the presentation sessions at the Copenhagen Center for Social Data Science (SODAS), The Hub for Mis- and Disinformation Research, Oxford University, EPSA (2024), IC2S2 (2023), and DPSA (2022).