Peer Reviewed

Data dependencies and funding prospects: A 1930s cautionary tale

Article Metrics

0

CrossRef Citations

PDF Downloads

Page Views

Misinformation studies relies, to some extent, on access to data from large technology firms, which also seed grants, sponsor events, and support think tanks working in the field. These companies, facing scrutiny from regulators and critics, have a stake in their portrayal. This essay recounts a pair of episodes in early radio research, as a cautionary tale. The Princeton Radio Research Project, the leading U.S. media research program of the 1930s, had multiple ties to the radio industry. The project’s leadership, and its main philanthropic sponsor, were keen to maintain good relations with the networks. A pair of critical researchers, James Rorty and Theodor Adorno, violated the project’s de facto ban on scrutinizing radio’s commercial underpinnings. They were both dismissed. Could ongoing access to data, and the prospect of future funding, lead today’s researchers—and even other, non-corporate patrons—to conclude that certain questions are too incendiary to pose?

Research Questions

- Do the experiences of media researchers with the 1930s radio industry bear lessons for the contemporary research landscape in misinformation studies?

- Are inquiries into sensitive issues of ownership and business models avoided or downplayed, as they were in the 1930s, when researchers rely on industry for access to data and future funding?

Essay Summary

- This essay traces the experience of two critical researchers, James Rorty and Theodor Adorno, at the Princeton Radio Research Project (PRRP) in the late 1930s.

- Both scholars saw their projects with the Rockefeller Foundation–funded PRRP shuttered for posing critical questions.

- In Rorty’s case—reported here for the first time—the PRRP director cut short a commissioned study for straying beyond the research organization’s narrow and politically calibrated remit.

- Likewise, Adorno, the German-Jewish emigre scholar, had his music project—one of four major PRRP initiatives—canceled after criticism from the radio industry.

- The PRRP, commissioned by Rockefeller to effect a reconciliation between the networks and educational broadcasters, was dependent on CBS and the broader industry for data.

- The PRRP’s associate director was Frank Stanton, CBS research director and the network’s future president.

- This essay provides a warning about the potential impact of big tech firms’ entanglements with digital research, including the threat of self-censorship and of data dependencies.

Implications

Misinformation studies finds itself in an awkward position. Many of its questions—around moderation and fact-checking, algorithmic news provision, and weaponized information—can’t be easily answered without help from Facebook, Google, and other big tech companies. The issue is that those firms have a stake in the answers. With increasing vigor, they have each mobilized lobbying and public relations operations to fend off threats to their core businesses. They are also major patrons of research. This patronage takes a variety of forms: in-house research shops, data access grants, support for university projects and institutes, event sponsorship, and non-university think tank donations. In most cases, researchers have formal autonomy, and even practical freedom, to pursue their questions. There is a risk, nevertheless, that conditions of data access and funding will move sensitive questions—like some firms’ ad-driven business models—off the scholarly agenda.

The case of early radio research offers a cautionary tale. In the mid-1930s, the Rockefeller Foundation turned to social scientists to help reconcile educational broadcasters and the commercial radio networks. From the beginning, the effort was dependent on the networks’ cooperation and sign-off. The foundation’s main research initiative, the Princeton Radio Research Project (PRRP), was reviewed by a committee of industry representatives and moderate educators (Buxton, 1994, pp. 155–167). The plan for the Princeton project was co-authored by CBS researcher Frank Stanton, who became the project’s associate director (Stanton, 1991, pp. 103–106). The Rockefeller-approved charter explicitly limited the project’s scope to audience research within the existing commercial radio system. That research program, in turn, depended on industry data from NBC and Stanton’s CBS (Lazarsfeld, 1940, pp. vii–ix, 16). The effect of all these ties to the networks was to make critical research on the industry—on the production side—off-limits.

This essay recounts the dismissal of two researchers, James Rorty and Theodor Adorno, who violated the Princeton project’s de facto ban on industry scrutiny. The project’s director, Paul Lazarsfeld, and the key Rockefeller sponsor, John Marshall, counted the industry’s ongoing cooperation as too important to risk.

The lesson from 1930s radio research isn’t that big tech firms might muzzle academic critics. The Rorty and Adorno cases demonstrate a subtler risk: that access to data, and the prospect of future funding, may lead researchers themselves—and even other, non-corporate patrons—to conclude that certain questions are too incendiary to pose. In the late 1930s, questioning the commercial basis of radio was beyond the scholarly pale. What, if anything, is too important to risk today?

Findings

Media research, circa 1937

After a fight with educational broadcasters, the radio industry won big with the passage of the Communication Act of 1934 (McChesney, 1995). In the bitter aftermath of the Act, the Rockefeller Foundation sought to reconcile the commercial networks with the educationalists’ moderate wing. The strategy hatched by the foundation’s John Marshall was to commission research on listeners, with the hope that the data would convince NBC and CBS that edifying programs weren’t a threat to their bottom lines (Buxton, 1994). By late 1937 Marshall’s research vehicle, the Princeton Radio Research Project (PRRP), was up and running under the leadership of Paul Lazarsfeld, a gifted Austrian psychologist and future eminence in American sociology.

Lazarsfeld’s associate directors, Hadley Cantril and Frank Stanton, had drafted the initial Rockefeller proposal. They tapped Lazarsfeld to take the helm when both men found themselves over-committed—Cantril in a new Princeton professorship and Stanton in his CBS research role (Fleck, 2011, pp. 166–168). The arrangement proved unstable: Lazarsfeld and Cantril had a series of nasty disputes, among other things over credit for the PRRP’s high-profile study of the 1938 Orson Welles “War of the Worlds” broadcast (Cantril, 1940; Pooley & Socolow, 2013). The relationship with Stanton was far more productive. The future CBS president, Stanton was then the network’s research head, and supplied the radio project with reams of data (Socolow, 2008; Lazarsfeld, 1940, p. viii).

Though nominally located at Cantril’s Princeton University, the project was actually run out of a former brewery in Newark, where Lazarsfeld had an established research center. To direct the PRRP’s Music program, Lazarsfeld turned to Theodor Adorno, a German-Jewish emigre affiliated with the leftist Institut für Sozialforschung. The Institut, the locus of what became widely known as the Frankfurt School, had relocated to Manhattan’s Morningside Heights after Hitler’s rise to power. Adorno was to split his time between the radio project and the Institut.

Lazarsfeld, meanwhile, recruited James Rorty, a poet and little-magazine intellectual, to assist Cantril in a planned study of radio commentators. (Rorty had been suggested by Columbia University sociologist Robert Lynd, co-author of Middletown [Lynd & Lynd, 1929] and an instrumental figure in Lazarsfeld’s rise.) Rorty was best-known for his scathing critique of the advertising industry, published in 1934 as Our Master’s Voice (Rorty, 1934a).

That Lazarsfeld had hired two men of the left was not surprising. Back in Vienna, he had been prominent in the Socialist Party’s youth wing and close to its leadership (Clavey, 2019). But Lazarsfeld had muted his own political commitments as he navigated, with shape-shifting savvy, his adopted country. A self-described “marginal man” blocked by anti-Semitism from an Austrian academic career, he understood the unspoken terms of the Rockefeller grant (Lazarsfeld, 1969, p. 302).

His two new collaborators were less compliant. Lazarsfeld cut Rorty off in 1939 after he refused to rein in his research. Adorno’s Music project, after a disastrous presentation to radio executives in 1939, was itself shuttered by Rockefeller’s Marshall.

Rorty’s muffled voice

Lazarsfeld retained Rorty in 1938 to assist Cantril, the PRRP associate director, on a planned “Commentator” study. Rorty’s relationship with Lazarsfeld was rocky from the start. The main point of contention was that Rorty kept studying radio commentators themselves—rather than the listener research that Rockefeller had agreed to.

Rorty had recently been fired from Fortune magazine, after the mortuary industry complained to editors about a planned exposé (Rorty, n.d.a, pp. 71–72). He was a rapier stylist and muckraker—roving for consumer scams—and a spirited member of New York’s anti-communist left (see Pope, 1988; Gross, 2008, chap. 1; Pooley, 2020). Rorty, who had worked in advertising, was especially caustic about his former profession—the “vile human backwater of Madison Avenue,” in a description from an unpublished memoir (Rorty, n.d.b, p. 82). His pamphlet Order on the Air! (Rorty, 1934b), a scabrous critique of commercial radio, appeared the same year as his book-length indictment of advertising (see Lenthall, 2007, pp. 30–39; Newman, 2004, pp. 60–63).

When Lazarsfeld met with Rorty in late 1937 to discuss the commentator project, he was already wary. He opted to commission just a month’s worth of research, with the plan to keep Rorty on if “he proves to have good sense.” In a memo to Cantril and Stanton, Lazarsfeld wrote that the probationary period would be a “good test as to how we should work with people of greater independence” (Lazarsfeld, 1937, p. 1). Rorty apparently passed the test, as he was hired to continue the work.

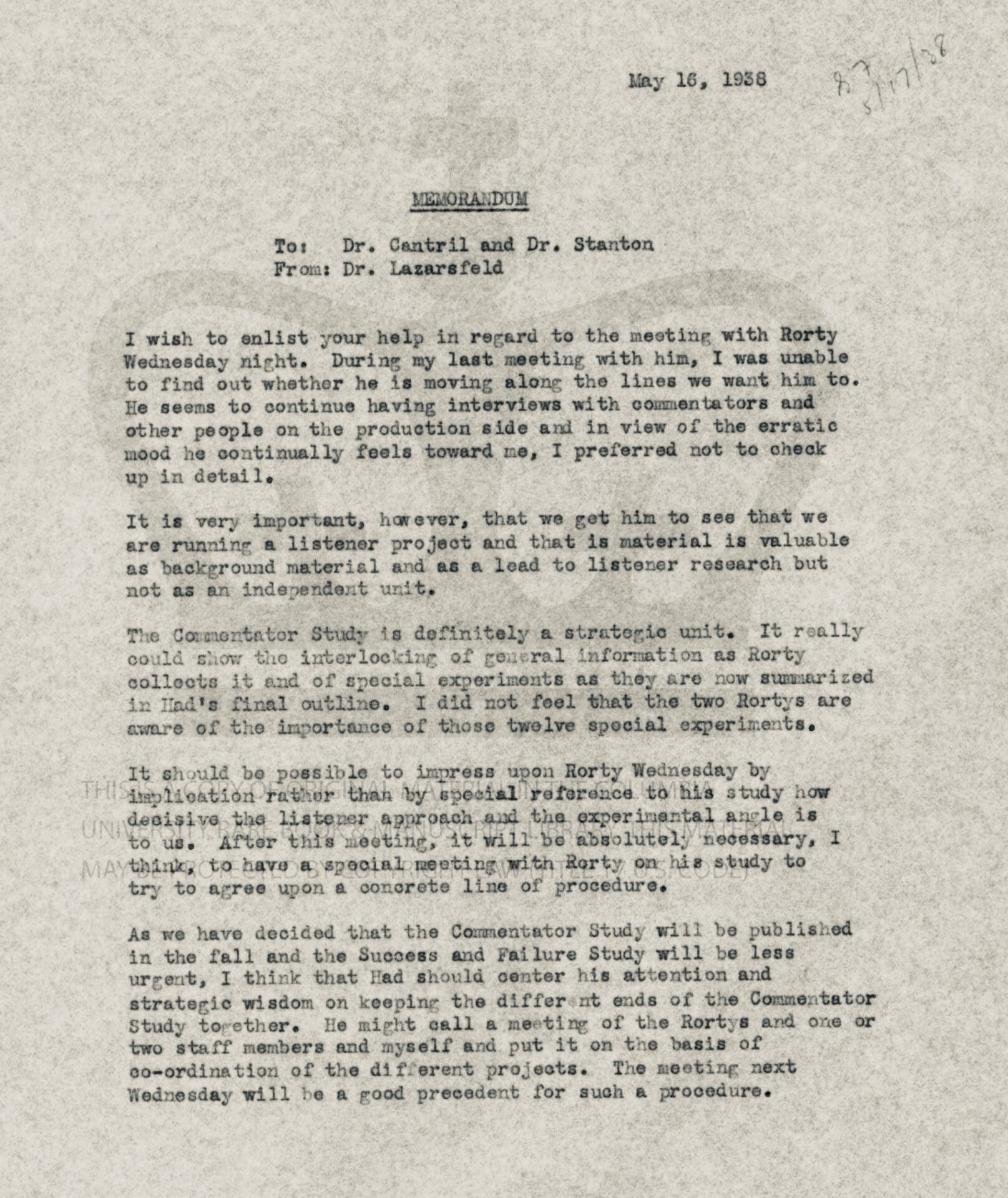

By spring 1938, however, Lazarsfeld was sounding the alarm. In another memo to Cantril and Stanton, Lazarsfeld (1938a) complained that Rorty was going rogue with his focus on the “production side.” When the two men last met, Lazarsfeld wrote, he couldn’t determine if Rorty was “moving along the lines we want him to.” The problem was that Rorty continued to interview radio commentators and “other people on the production side.” It is “very important,” Lazarsfeld wrote, that “we get him to see that we are running a listener project.” Rorty’s production-side interviews could be valuable as background material, but “not as an independent unit.” Lazarsfeld vowed to impress on Rorty “how decisive the listener approach” is. The memo closed with a plea to Cantril—who Lazarsfeld was feuding with at the time—to step up his work on the study.

The ambitious Cantril was, it turns out, already in Rorty’s debt. He had, around this time, commissioned Rorty to ghost-write an article on radio propaganda, to be published under Cantril’s name (Sproule, 1997, pp. 139–140). The article was to appear in the bulletin of the Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA), a New York–based hub of propaganda-defense education. Alarmed by the industry criticism in Rorty’s draft, Cantril—the IPA’s founding chairman and a board member—demanded an overhaul, but even the revised version he judged too critical. Cantril pleaded for the article to run under another scholar’s name—someone not “trying to get another $67,000 out of the Rockefeller Foundation for radio research,” as he put it in a letter to the bulletin’s editor (quoted in Sproule, 1997, p. 139).

The watered-down article ran anonymously in June (Anonymous, 1938). Whatever its defanging, the published version still centers its analysis of the “American System” on the profit-seeking couplet of advertisers and the networks. Sponsored programs, Rorty wrote, “bring to us the many propagandas of commercial advertising. . . . Many or most are sweetened and made palatable by music or other entertainment—the formula of the old time medicine show” (p. 53). The article goes on to describe the national radio networks as a “response to the need of advertisers to reach a maximum number of listeners” (p. 54). Like American movies, American radio has a tendency therefore to “perpetuate commonly accepted stereotypes.” Despite such “restrictions”—and here was the half-grudging concession-by-revision—stations do furnish “something of that freedom of controversy” that is the “essence of democracy” (p. 55). The dense four-page article includes a conspicuous quotation from Cantril lauding the radio networks’ commitment to “freedom of the air in America” (p. 54, quoting Cantril & Allport, 1935).

So Cantril was in no position to bring Rorty’s PRRP work in line with the Rockefeller mandate. Rorty’s relations with Lazarsfeld continued to deteriorate over the summer, after Rorty submitted a draft report based on his interviews. In a September memo to Cantril and Stanton, Lazarsfeld (1938b) appealed to Cantril to “really and actively centralize the commentator material in his hands.” He repeated that he’d like to see Cantril’s listener experiments “put into the center of the report,” so that “Rorty’s draft will only be background material.” But Lazarsfeld was still sparring with Cantril, his would-be savior for the Rorty problem. He closed the memo in the passive-aggressive third person: “I have definite ideas of how we could get Had’s co-operation on that,” which “should make this year less disturbing for him” (p. 2).

Lazarsfeld (1938c), in a follow-up memo, complained that Rorty had lied about time spent on the commentator project. Rorty had, Lazarsfeld added, kept himself “absolutely isolated” from the PRRP. Despite the criticisms, Rorty remained on the PRRP payroll for an additional year.

This was true even though Cantril moved to abandon the commentator project altogether. When Orson Welles’ “War of the Worlds” seemed to panic the nation in October, he seized control of the emergency study that Stanton, Lazarsfeld, and Herta Herzog (Lazarsfeld’s wife) had rushed to establish in its wake. (Cantril also moved to block the IPA’s involvement with the study.) Relations between Lazarsfeld and Cantril were, by then, irreparable. Cantril (1940) refused to acknowledge Herzog’s pivotal role in the study, which he published as The Invasion from Mars under his own name in 1940. He used the book to convince Rockefeller to fund a new research center under his leadership—to divorce Lazarsfeld, in other words (Pooley & Socolow, 2013).

Rorty, a year later, was still affiliated with the radio project, even as Lazarsfeld rushed to assemble the PRRP’s studies into a book (Lazarsfeld, 1940) in a bid to convince Rockefeller to renew the grant (now sans Cantril). In a half-embittered, half-solicitous letter to Rorty in the fall of 1939, Lazarsfeld wrote, “I am afraid that you are not aware of the extent to which you have troubled our Project” (quoted in Lazarsfeld, 1939, pp. 1–2). Citing Rorty’s intransigence, the letter added that the “material you have collected did not prove of any value to us.” Lazarsfeld quickly backtracked, admitting that Rorty’s “very interesting chapter” could not be used because it (raising the listenership issue) had “no relation with the general line of the Project’s procedure.” Still, Lazarsfeld noted, he might want to use the “very stimulating reports you wrote” on the commentator interviews as a “sort of illustrative appendix”—partly so he would have something “to show” for “our cooperation with you.” Lazarsfeld closed with the charge that Rorty had wasted a great deal of money, and flatly refused further payment.

The commentator study was never completed, and Rorty’s reports and transcripts were, in the end, left out of Lazarsfeld’s (1940) hurried book, Radio and the Printed Page. Lazarsfeld had instead recruited Samuel Stouffer, the University of Chicago sociologist and future luminary, to analyze Gallup data on radio news, as a substitute for the commentator study (Lazarsfeld, 1939, p. 1; Lazarsfeld, 1940, p. viii). Stouffer’s text was cautious and anodyne; its main conclusion was that the audience of commentator programs skews wealthy and educated (Lazarsfeld, 1940, p. 241). Rorty’s name appears just once, in a footnote—credited for an experiment idea (p. 246).

Rorty’s drafts and interviews transcripts are apparently lost. It is ironic that the only write-up of the material appeared in the Propaganda Analysis bulletin—the article that Cantril had found too hot to claim (Anonymous, 1938). His reticence was the same as Lazarsfeld’s, whatever their other differences: Rorty had deigned to study the production side. In the anonymous article’s closing section on “Radio Commentators,” Rorty wrote that radio news “offers constant opportunity for propaganda by commission and omission, by over-emphasis and under-emphasis” (p. 56). He pointed to the speaker’s voice as an unmarked vessel of “editorial emphasis” which—together with sheer audience size—suggests that commentators “may shape public opinion much more than newspaper editorials” (p. 56).

A discordant note

The Adorno story is better-known, partly because he and Lazarsfeld published dueling, side-by-side accounts of the episode (Lazarsfeld, 1969; Adorno, 1969; see also, e.g., Morrison, 1978; Fleck, 2011, chap. 5; Jenemann, 2007, chap. 2). In his rendition, Adorno—referring to Rockefeller’s explicit stipulation that the PRRP’s studies not question the country’s commercial radio system—wrote: “I cannot say that I strictly obeyed the charter” (p. 343).

The Adorno hiring came late in the Frankfurt Institut’s relocation to New York City. In 1934 the Institut’s director and central figure, Max Horkheimer, had secured a building and Columbia University affiliation, with a crucial boost from sociologist Lynd (Wheatland, 2009, chap. 1). By 1936—before the PRRP’s founding—Lazarsfeld had begun working on Institut studies, in a connection established by Lynd. When the Rockefeller grant came through, the radio project and the Institut—despite some obvious points of tension—established something like a revolving door: Lazarsfeld continued to assist with Institut studies, and also hired Horkheimer Circle figures such as Adorno and Leo Lowenthal to staff his radio project. This sometimes-awkward collaboration endured through the late 1940s, when Horkheimer and Adorno accepted an invitation to re-establish the Institut in postwar Frankfurt (Wheatland, 2005). By then Lazarsfeld had become, somewhat improbably, a leading Columbia sociologist. The radio project, renewed by Rockefeller in 1940, had swapped out its affiliation with Princeton for Columbia—with, again, Lynd’s decisive help—and in 1944 changed its name to the Bureau of Applied Social Research (Pooley, 2006, pp. 265–266).

So Lazarsfeld and Adorno, to paraphrase historian Thomas Wheatland, weren’t such an odd couple. In the fall of 1937, when Lazarsfeld reached out through Horkheimer, Adorno was struggling to finish an Oxford doctorate. He accepted the fellow emigre’s offer, at almost the same moment that Lazarsfeld brought Rorty on board. Once installed in the former brewery—which he described as “Kafka’s Nature Theater of Oklahoma”—Adorno took up the appointed study of radio music (Adorno, 1969, p. 342). Though he agreed to employ some of Lazarsfeld’s audience study methods, he insisted (as he wrote in his acceptance letter) that the “decisive information” rests in the “relations of production on which consumption depends” (quoted in Fleck, 2011, p. 180). Lazarsfeld then reminded his new colleague that studying musicians and production was off-limits: “The basic trends of [the Rockefeller grant agreement] are still binding for us” (p. 182).

Adorno did not strictly obey the charter. By 1940 he had produced a series of papers and at least three book-length manuscripts (Levin & von der Linn, 1994). A handful of the papers were published in this period—just one in a PRRP volume—with the rest seeing print only recently (Adorno, 1941, 1945; Adorno & Simpson, 1941; Adorno, 2009). The enormous output is difficult to summarize in a few sentences (see Jenemann, 2007, pp. 53–104, for an unusually lucid overview). At the core of Adorno’s project was a rejection of the PRRP’s listener-data approach. Though he conducted audience interviews and (with staff help) large-scale listener surveys, Adorno insisted on treating the conditions of radio production, the technology of transmission, and the social conditions of listening as an analytic whole. He referred to the “unity of the radio phenomenon,” itself a kind of mirror of American society’s root contradictions (Adorno, 2009, p. 73). Radio, as it is produced, broadcast, and consumed, reflects and reinforces the commodity form—“the ideal of Aunt Jemima ready-mix for pancakes,” as he memorably put the point, “extended to the field of music” (Adorno, 1945, p. 211).

By all accounts, Lazarsfeld tried to work with Adorno, granting him critical space and defending—up to a point—his theoreticist heterodoxies. He even used Adorno to draw a favorable contrast to Rorty, in a 1938 memo to Cantril and Stanton (Lazarsfeld, 1938c). Unlike Rorty, Adorno has “contributed a great number of original ideas” to the Project. Yes, Lazarsfeld continued, I “still have some difficulty in getting” Adorno “down to earth,” but there can be “no doubt of his originality and the fruitfulness of his approach.” And Adorno, in contrast to Rorty, considers himself a part of the project.

But Lazarsfeld drew the line at Adorno’s first lengthy manuscript, whose publication, he wrote, would jeopardize the PRRP’s renewal (Fleck, 2011, pp. 184–185). It was not, however, Lazarsfeld who decided to drop Adorno. It was Marshall, the Rockefeller official, who made the project’s extension conditional on Adorno’s removal. The precipitating event was an October 1939 talk, “On a Social Critique of Radio Music”—attended, fatefully, by network officials and Marshall, in addition to project scholars (Morrison, 1978, p. 340). Adorno did not mince words, stating up front his premise that the “relation of vested interests to radio music is that music, under present radio auspices, serves to keep dormant critical analyses by listeners of their material social relations” (Jenemann, 2007, pp. 48–50). He went on to dismiss the PRRP’s empirical study of listeners as “administrative research” (a label that Lazarsfeld [1941] would adopt and defend in a now-famous 1941 essay published in the Institut’s journal).

Marshall had not expected the grant to underwrite a critique of radio’s “soporific effect.” By early 1940, he had decided that Adorno had to go, reasoning in his diary that Adorno’s work would put the industry “definitely on the defensive, with the probable result that they would be left more inclined to rationalize those deficiencies than to attempt any remedy for them.” Adorno must abandon his unfinished PRRP studies, he added, since they “do not come within the [Horkheimer] Institute’s program” (quoted in Jenemann, 2007, p. 50). Lazarsfeld tried to negotiate a compromise, one that would keep the exiled scholar affiliated with the project, but industry executives and Marshall stood firm (Fleck, 2011, p. 199).

Adorno failed to secure alternative funding to complete the radio studies. In 1941, he and Horkheimer moved to Los Angeles, joining a remarkable community of German refugee-intellectuals that scholars have aptly dubbed Weimar on the Pacific (see Bahr, 2007). Traumatized by reports of the Holocaust and the German conquest of Europe, the pair drafted their dark and penetrating critique of Western reason (“from the slingshot to the megaton bomb,” as Adorno [1973, p. 320] later phrased it), published as The Dialectic of Enlightenment in 1947 (Horkheimer & Adorno, 2002). Their notorious “Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception” essay, with plain roots in some of Adorno’s radio work, was a chapter.

Walking the tightrope

The Rockefeller ban on production-side research was, it turns out, selectively enforced. In 1939, at the height of his struggles with Rorty and Adorno, Lazarsfeld accepted funding from a station-owning newspaper trade group to tabulate the relationship between radio news and ownership. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had just opened hearings on whether, and how, newspapers could own radio stations, so the station-owning group was investing, of course, in Lazarsfeld’s potential help. The commissioned project, he (1969) later wrote, was “an important source of income for us” (pp. 316–317). Though Lazarsfeld shared his data with the FCC, he (1940) made no mention of the study nor the sponsorship in a studiously neutral five-page overview of the “struggle between radio and press for advertising accounts” in Radio and the Printed Page (pp. 272–276). He did, however, document the heavy advertising losses newspapers had taken, speculating that single-market newspaper monopolies would grow as a result. “The social and political consequences of such a trend will be interpreted variously, depending upon the point of view of the writer,” he wrote, before proposing a “compromise”: that radio and the press divide the advertising spoils (pp. 274–275).

What’s interesting about the double standard—and the PRRP clashes as a whole—is that Lazarsfeld was no corporate shill. He was instead an inventive and occasionally critical scholar, even through the 1940s, as his reliance on the industry for funding and data deepened further. The crucial point is that he knew what not to say, and what not to study, when his patrons were listening. So his most public statements about media effects—in Personal Influence (Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955) and in his student Joseph Klapper’s The Effects of Mass Communication (Klapper, 1960)—told the industry what it wanted to hear, that media effects are minimal. (Klapper, when he published his book, was the CBS research director, the very role that Stanton had held on his way to the network’s presidency.)

In a 1948 address, Lazarsfeld explained his strategy:

“Those of us social scientists who are especially interested in communication research depend upon the industry for much of our data. Actually, most publishers and broadcasters have been very generous and cooperative in this recent period during which communications research has developed as a kind of joint enterprise between industries and universities. But we academic people always have a certain sense of tightrope walking: At what point will they shut us off from the indispensable sources of funds and data?” (Lazarsfeld, 1948, pp. 115–116)

Lazarsfeld’s question, as internalized by today’s tightrope-walkers, remains apposite.

Methods

This essay used intellectual–historical methods to reconstruct a pair of overlapping episodes in the history of early radio research. The task involved establishing context through the secondary literature, close reading of primary published work, and investigating relevant archives and oral histories. The main archival collections were the Lazarsfeld papers at Columbia University and Rorty’s papers at the University of Oregon. I also consulted the Rockefeller Foundation archives at the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, New York. The Adorno Archiv at the University of Frankfurt was not consulted, because the relevant materials are well-documented in the secondary literature.

One challenge of archival research is the fragmentary nature of the evidence. The accidents and vagaries of preservation can lend undue weight to surviving materials. In this case, the professional trajectories of the main actors help account for an important gap. Reflective of an academic with a stable institutional base, Lazarsfeld’s papers are far more extensive than the journalist Rorty’s. This essay identifies gaps in the evidence where relevant.

Topics

Bibliography

Adorno, T. W. (1941). The radio symphony. In P. F. Lazarsfeld & F. Stanton, Radio Research 1941 (pp. 110–139). Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

Adorno, T. W. (1945). A social critique of radio music. The Kenyon Review, 7(2), 208–217. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4332589

Adorno, T. W. (1969). Scientific experiences of a European scholar in America. In D. Fleming & B. Bailyn (Eds.), The intellectual migration: Europe and America, 1930–1960 (pp. 338–379). Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Adorno, T. W. (1973). Negative dialectics (E. B. Ashton, Trans.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1966)

Adorno, T. W. (2009). Current of music: Elements of a radio theory (R. Hullot-Kentor, Ed.). Polity.

Adorno, T., & Simpson, G. (1941). On popular music. Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, 9(1), 17–48.

Anonymous. (1938). Propaganda on the air. Propaganda Analysis, 1(9), 53–57.

Bahr, E. (2007). Weimar on the Pacific: German exile culture in Los Angeles and the crisis of modernism. University of California Press.

Buxton, W. J. (1994). The political economy of communications research. In R. E. Babe (Ed.), Information and communication in economics (pp. 147–175). Kluwer.

Cantril, H., & Allport, G. (1935). The psychology of radio. Harper & Bros.

Cantril, H., with the assistance of Gaudet, H., & Herzog, H. (1940). The invasion from Mars: A study in the psychology of panic. Princeton University Press.

Clavey, C. H. (2019, July 15). Resiliency or resignation: Paul F. Lazarsfeld, Austro-Marxism, and the psychology of unemployment, 1919–1933. Modern Intellectual History, 18(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479244319000192

Fleck, C. (2011). A transatlantic history of the social sciences: Robber barons, the Third Reich and the invention of empirical social research. Bloomsbury USA.

Gross, N. (2008). Richard Rorty: The making of an American philosopher. University of Chicago Press.

Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T. W. (2002). Dialectic of enlightenment (G. S. Noerr, Trans.). Stanford University Press. (Original work published 1947)

Jenemann, D. (2007). Adorno in America. University of Minnesota Press.

Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955). Personal influence: The part played by people in the flow of mass communications. Free Press.

Klapper, J. T. (1960). The effects of mass communication. Free Press.

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1937, December 15). [Memo to H. Cantril and F. Stanton]. Paul Felix Lazarsfeld papers (Box 3A, Frank Stanton & Hadley Cantril folder). Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1938a, May 16). [Memo to H. Cantril and F. Stanton]. Paul Felix Lazarsfeld papers (Box 3A, Frank Stanton & Hadley Cantril folder). Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1938b, September 22). [Memo to H. Cantril and F. Stanton]. Paul Felix Lazarsfeld papers (Box 3A, Frank Stanton & Hadley Cantril folder). Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1938c, November 7). [Memo to H. Cantril and F. Stanton]. Paul Felix Lazarsfeld papers (Box 3A, Frank Stanton & Hadley Cantril folder). Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1939, September 8). [Memo to H. Cantril and F. Stanton]. Paul Felix Lazarsfeld papers (Box 3A, Frank Stanton & Hadley Cantril folder). Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1940). Radio and the printed page: An introduction to the study of radio and its role in the communication of ideas. Duell, Sloan & Pearce.

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1940). Radio and the printed page: An introduction to the study of radio and its role in the communication of ideas. Duell, Sloan & Pearce.

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1941). Remarks on administrative and critical communications research. Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, 9(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.5840/zfs1941912

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1948). The role of criticism in the management of mass media. Journalism Quarterly, 25(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769904802500201

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1969). An episode in the history of social research: A memoir. In D. Fleming & B. Bailyn (Eds.), The intellectual migration: Europe and America, 1930–1960 (pp. 270-337). Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Lenthall, B. (2007). Radio’s America: The Great Depression and the rise of modern mass culture. University of Chicago Press.

Levin, T., & von der Linn, M. (1994). Elements of a radio theory: Adorno and the Princeton Radio Research Project. Musical Quarterly, 78(2), 316–324. https://www.jstor.org/stable/742546

Lynd, R. S., & Lynd, H. M. (1929). Middletown: A study in contemporary American culture. Harcourt, Brace.

McChesney, R. W. (1995). Telecommunications, mass media, and democracy: The battle for the control of US broadcasting, 1928–1935. Oxford University Press.

Morrison, D. E. (1978). Kultur and culture: The Case of Theodor W. Adorno and Paul F. Lazarsfeld. Social Research, 45, 331–355. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40970336

Newman, K. M. (2004). Radio active: Advertising and consumer activism, 1935–1947. University of California Press.

Pooley, J. (2006). An accident of memory: Edward Shils, Paul Lazarsfeld and the history of American mass communication research [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Columbia University.

Pooley, J. (2020). James Rorty’s voice: Introduction to the mediastudies.press edition. In J. Rorty, Our master’s voice: Advertising (pp. xiv–xxxi). mediastudies.press. https://doi.org/10.32376/3f8575cb.76247d1f

Pooley, J., & Socolow, M. (2013). Checking up on The Invasion from Mars: Hadley Cantril, Paul Lazarsfeld, and the making of a misremembered classic. International Journal of Communication, 7, 1920–1948. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2117

Pope, D. (1988). His master’s voice: James Rorty and the critique of advertising. Maryland Historian 19(1), 5–15.

Rorty, J. (n.d.a). It happened here. [Unpublished memoirs, version 2]. James Rorty papers (Series III, Box 2, Folder 5). University of Oregon Special Collections.

Rorty, J. (n.d.b). It happened here. [Unpublished memoirs, version 1, continued]. James Rorty papers (Series III, Box 2, Folder 4). University of Oregon Special Collections.

Rorty, J. (1934a). Our master’s voice: Advertising. John Day.

Rorty, J. (1934b). Order on the air! John Day.

Socolow, M. J. (2008). The behaviorist in the boardroom: The research of Frank Stanton, Ph.D. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(4), 526–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437214

Sproule, J. M. (1997). Propaganda and democracy: The American experience of media and mass persuasion. Cambridge University Press.

Stanton, F. (1991). Oral history of Frank Stanton. Columbia University Oral History Office.

Wheatland, T. (2005). Not-such-odd couples: Paul Lazarsfeld and the Horkheimer circle on Morningside Heights. In D. Kittler & G. Lauer (Eds.), Exile, science and Bildung (pp. 169–184). Palgrave Macmillan.

Wheatland, T. (2009). The Frankfurt School in exile. University of Minnesota Press.

Funding

The author did not receive funding for this work.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Ethics

The data for the project were obtained from archival sources and thus were exempt from IRB review.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

The data for the project is available in publicly accessible archival collections, as cited in the Bibliography.