Peer Reviewed

Clarity for friends, confusion for foes: Russian vaccine propaganda in Ukraine and Serbia

Article Metrics

0

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

Page Views

This paper examines how Russia tailors its vaccine propaganda to hostile and friendly audiences, like Ukraine and Serbia. Web scraping of all articles about vaccines on Russian state-owned websites from December 2020 to November 2021 provided data for quantitative topic modeling and qualitative analysis. This revealed that the Kremlin muddles issues and sows confusion for Ukrainians but feeds Serbians focused, repetitive narratives. Therefore, countering Russian propaganda proactively also requires a tailored approach. Journalists and public communications officials should clarify information and separate unrelated issues in Russia-hostile places like Ukraine but add nuance and context to narratives in Russia-friendly places like Serbia.

Research Questions

- What are the structural differences in the coverage of COVID-19 vaccines in Russian propaganda outlets targeting Ukraine and Serbia, which have majority anti-Russia and pro-Russia publics respectively?

- How do specific Russian COVID-19 vaccine propaganda narratives in Ukraine and Serbia compare?

Essay summary

- The pandemic presents a rare opportunity for directly-comparable analysis of Russian information operations on an urgent, policy-relevant issue: COVID-19 vaccines.

- This study uses data scraped from all 2,417 vaccine-related articles in Sputnik Serbia and 1,552 articles in Ukraina.ru, both Russian state-owned outlets, from December 2020 through November 2021. To test quantitative findings, a random sample of 20 articles per country was also analyzed.

- The breadth of coverage in Ukraina.ru articles was wider, and articles contradicted each other, while Sputnik Serbia covered fewer topics more consistently.

- Narratives in Ukraina.ru touched a wide range of topics, such as geopolitics, Russia’s vaccination campaign in the Donbass, and criticism of the Ukrainian government.

- Sputnik Serbia focused on positive coverage of the Russian vaccine Sputnik V and the Serbian government’s vaccination campaign.

- This research allows journalists to take a more proactive, context-based approach to countering Russian propaganda.

- In Ukraine and potentially other Russia-hostile countries, journalists and public relations officials should address misinformation by simplifying and clarifying narratives, including separating vaccines from other political issues.

- In Serbia and potentially other Russia-friendly countries, the opposite approach of providing more nuanced narratives and putting Russian claims in context would be most helpful.

Implications

Serbia and Ukraine are two of many countries around the world that are victims of extensive and effective Russian information operations related to COVID-19 vaccines. This issue has received an enormous amount of attention (Barnes, 2021; EU vs. Disinfo, n.d.; Gray & Edwards, 2020; Hyde, 2021; Kier & Stronski, 2021; Krainčanić, 2021; Kuzmanovic et al., 2021; Reyting Group, 2021; Sunter & Cappello, 2021; Thomas et al., 2020; UCMC, 2021). The magnitude of the problem makes it important in and of itself, but the circumstances also present a rare opportunity to understand Russian information strategy more broadly by directly comparing cases with the same topic and timing.

Harold Lasswell (1927) wrote that propaganda is directed at the ally, enemy, and neutral sides. However, research on modern Russian information campaigns almost exclusively focuses on the enemy. The conclusion of this prolific body of research is that the Kremlin’s uniform strategy is to sow information chaos, characterized by a lack of narrative consistency, to make truth seem subjective (Fitzgerald & Brantly, 2017; Global Engagement Center, 2020; Jankowitz, 2018; Singer & Brooking, 2018; Will, 2021).1While focused on the domestic manifestation of this idea, one of the best books about this is Pomerantsev’s Nothing is true and everything is possible: The surreal heart of the new Russia (2015). Leaders of Russia have long operated under the assumption that information can be manipulated for political purposes; see Lenin (1902).

This paradigm works well for understanding Russian vaccine propaganda in Ukraine, a country hostile to Russia. However, it does not apply to Russia’s information campaign in Serbia, whose public is pro-Russia. Russia may have a rich arsenal of divisive and anti-West narratives that it uses in other contexts in Serbia (Stiftung, 2018; Stronski & Himes, 2018), but on vaccines, Sputnik Serbia is taking the opposite approach to information chaos. It conducts its information campaigns through repetition of highly consistent pro-Russia narratives. Repetition, which psychological research shows to be highly effective, is a known component of Russian propaganda, but the finding that Russian narratives are consistent in Serbia contradicts prior research (Paul & Matthews, 2016).

This can be explained through the logic of the audiences’ receptivity to Russian propaganda, hinting at the Kremlin’s diverging motivations. In Ukraine, Russia is creating a package of pro-Russian ideas about geopolitics, domestic politics, and vaccines for its readers. If one part of the narrative resonates, the reader might be more open to a pro-Russian position on an unrelated topic included in the same article. In Serbia, where Russia can assume support from its readers on other topics, which can be addressed independently, vaccine messaging can be simpler. Additionally, attempts to polarize society through inconsistency and contradictions is a well-documented Russian technique, including in Ukraine (DiResta et al., 2018; Peisakhin & Rozenas, 2018). In majority-hostile publics, isolating and radicalizing receptive segments of the population helps achieve the Kremlin’s goal of increasing internal conflict. It would not be logical to adopt the same approach in a friendly country like Serbia, where the Kremlin benefits from maintaining a stable, status-quo political environment.

This research has implications for what narratives journalists and civil society actors in each country should use to counter Russian propaganda, including public health NGOs, local independent journalists, and Western media outlets like Radio Liberty, Voice of America, BBC, and Deutsche Welle. It can also inform the government’s public outreach on vaccines, although these recommendations are unlikely to be adopted by the Serbian government, which is closely aligned with Russia (Kara-Murza, 2022). So far, targets of Russian information campaigns have struggled to proactively counter-narratives (Jones, 2018). This is a problem because the Kremlin prioritizes rapid dissemination of narratives, as people usually believe what they read first (Paul & Matthews, 2016).2The U.S. campaign to proactively combat information amidst the ongoing Russian aggression against Ukraine is a welcome change in approach (Merchant, 2022). However, these efforts still rely on knowledge of specific future information narratives gained through intelligence. This research allows for a broader, structural understanding of Russian propaganda that allows for a more proactive approach even in the absence of forewarning about upcoming Russian information campaigns. This research provides a better understanding of the structure of Russian propaganda narratives, not just the specific ones used currently, in different political contexts. This can help those fighting disinformation on vaccines and other topics proactively use their own narrative structures that are most likely to be effective.

When Russia is trying to muddle narratives and conflate vaccines with other political issues, as in Ukraine and possibly other hostile contexts, the appropriate countermeasure would be to use clear and concise narratives focused only on vaccines. For example, journalists—including op-ed writers—should refrain from discussing the Russian vaccines alongside Russian military action in Ukraine, even if it is tempting to use both as examples of Putin’s geopolitical ambitions. Public health organizations and government officials responsible for pandemic outreach may want to avoid statements on politics entirely. This would help Ukrainians, including in the more pro-Russia separatist-held regions, develop a nuanced set of opinions about vaccines and other issues that are not bundled as strictly pro-Russia or anti-Russia, and could reduce polarization. The approach of addressing issues one at a time can be applied to counter other Russian information campaigns, including narratives about Putin’s current invasion of Ukraine.

Serbia and perhaps other Russia-friendly contexts require a different approach. Adding nuance to issues that the Russian government is trying to frame as simple would dampen the impact of propaganda. While it would be unhelpful to take the Russian tactic in Ukraine of conflating only tangentially related issues—this would only fuel the fire, since Sputnik Serbia frequently comments on how the West likes to tie vaccines to geopolitics (RS #879, #989, #1533)3For ease of reference and to distinguish outside research from the random sample, articles in the random sample used for qualitative analysis are denoted by their number in the overall corpus for each outlet. RS refers to the Sputnik Serbia corpus, and UK refers to Ukraina.ru. Citations for sample articles are provided in the Appendix.—journalists and public health organizations and officials can provide context and caveats to Russian claims about Sputnik V and the Serbian government’s pandemic response. For instance, they could acknowledge data on the effectiveness of Russian vaccines, but also note the source of the data and compare it to alternative vaccines. Such additions may help even pro-Russia citizens moderate their views.

This study shows that further data-driven research is necessary to combat Russia’s information campaigns proactively. This issue has become even more urgent since the Russian invasion of Ukraine; initial reports have already shown how the Kremlin is tailoring its propaganda, including for the friendly domestic audience and hostile Ukrainian audience (Miburo, 2022). There has been some research on how Russia targets different narratives in various countries, including Ukraine and Serbia (U.S. Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, 2018). However, such research does not address structural variation of information campaigns, which limits the ability of journalists and others to effectively counter it even before specific Russian narratives emerge. To my knowledge, there are only two other studies that address whether countries differentiate propaganda narratives used on adversaries and allies (Golan & Viatchaninova, 2014; Melki & Jabado, 2016), so these findings should be tested in other contexts. It is also critical to understand how tactics and platforms targeting specific audiences, not just narratives, differ when used on allies versus adversaries. This paper addresses what counter-narratives to Russian propaganda should be, but not how, where, and to whom they would be most effectively deployed, a subject for future research.

Findings

Finding 1: Vaccine coverage in Russian propaganda incorporates a broad range of topics and is inconsistent in Ukraine but is narrowly focused and consistent in Serbia.

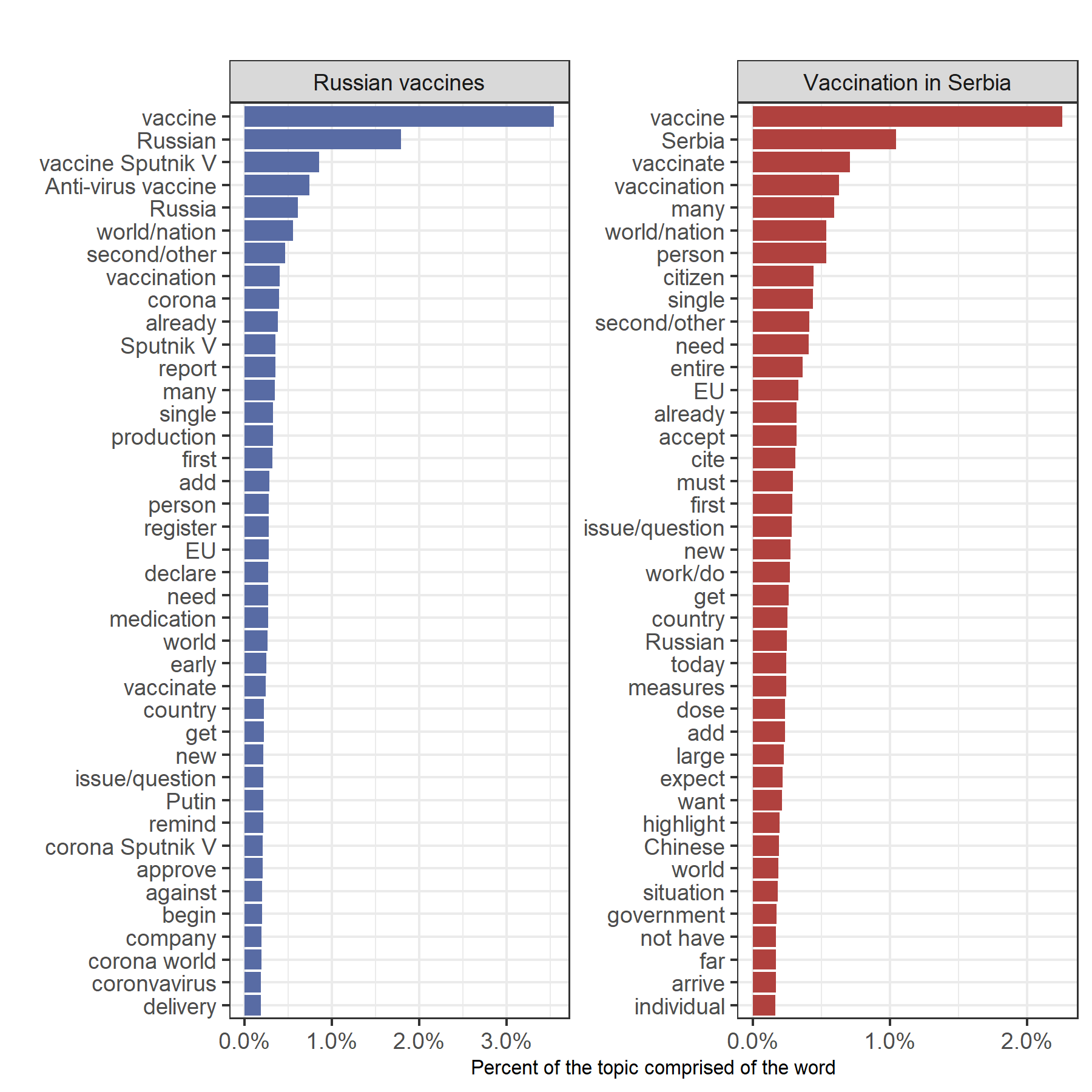

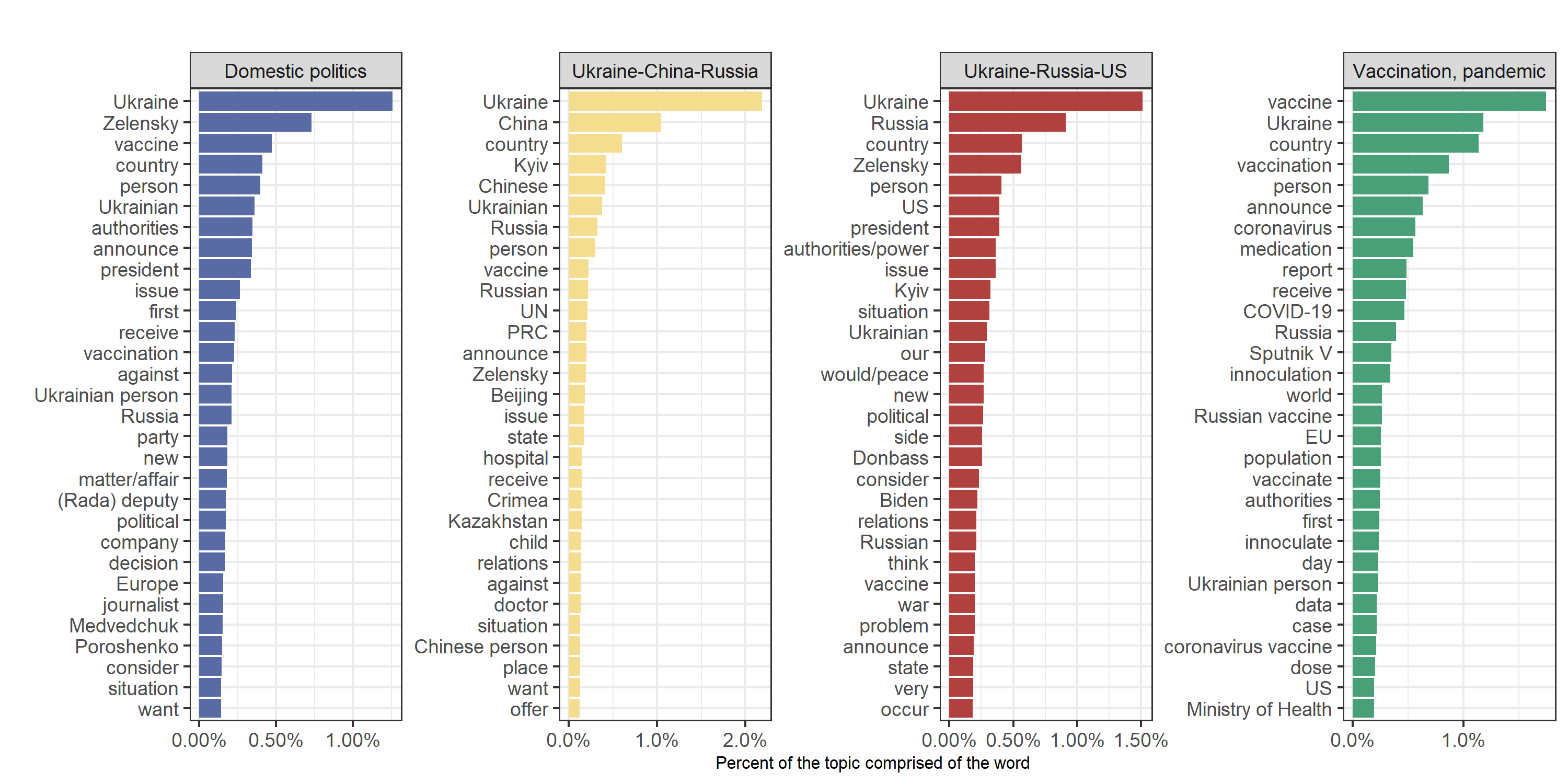

Topic models, which use quantitative methods to group articles into topics and reveal the most frequently used words in those topics, show that the range of Ukraina.ru articles about vaccines is wider than that of Sputnik Serbia (see Figures 1 and 2). Both outlets covered domestic vaccination campaigns and Sputnik V, but these were the only two topics in Sputnik Serbia reporting. Ukraina.ru incorporated vaccines into domestic politics to such an extent that it formed its own topic, which included opposition politicians like Poroshenko and Medvedchuk. In contrast, not even the Serbian president was in the top 40 words of either topic. Ukraina.ru articles about vaccines also mentioned geopolitics far more often, forming two additional topics. Qualitative analysis confirmed that vaccines featured in Ukraina.ru articles on issues from censorship to war in the Donbass, while in Sputnik Serbia, articles including the word vaccine were almost entirely about vaccines.

Qualitative analysis showed that even in a small random sample of Ukraina.ru articles, coverage is often contradictory, except where Russia’s key interests – Sputnik V and the Donbas – are concerned. This includes whether Ukraine should use AstraZeneca (UK #808, #900), when Ukraine would likely receive Western vaccines (UK #1107, #1374), praise and criticism of China (UK #1004, #274, #37), and the varying assessments of the Ukrainian government’s vaccination efforts (UK #309, #1275, #1107, #1004, #1080), although the latter was mostly negative. Qualitative analysis did not reveal any contradictions in Sputnik Serbia. For example, all articles about China in the Sputnik Serbia sample reiterated that the government was excited to get Chinese vaccines and made the right decision to use all available vaccines (RS #1612, #1949, #2131), contrasting with mixed messaging on China in Ukraina.ru.

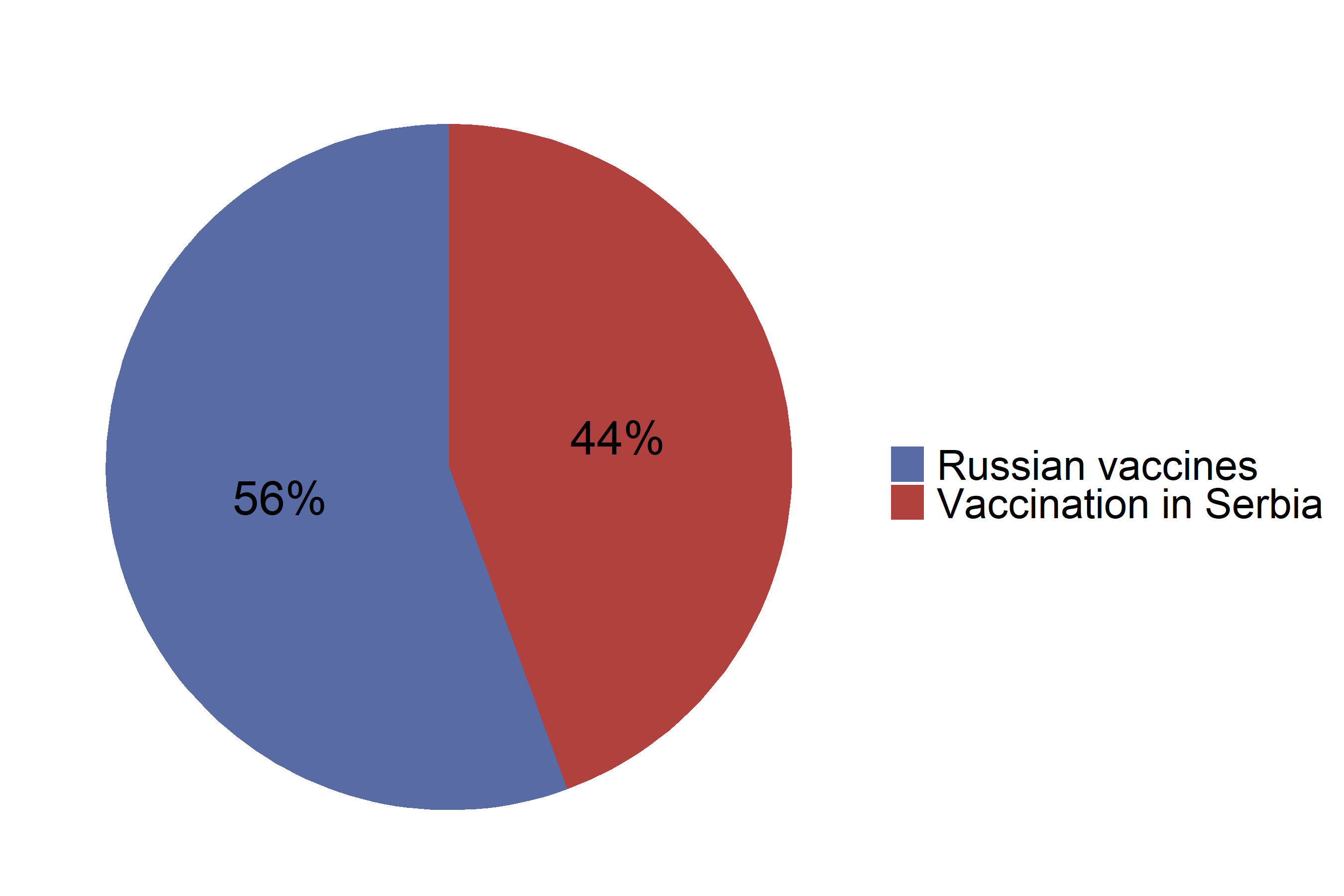

Finding 2: Russian vaccine narratives in Serbia are almost exclusively positive or neutral coverage of Sputnik V and the Serbian government’s vaccination campaign.

Only two clear topics emerged in Sputnik Serbia’s vaccine coverage (see Figure 1). The first is the Russian vaccine Sputnik V. Over half the articles are on this topic, and Serbia is not even one of the top forty words, so most articles regarding vaccines in Sputnik Serbia are not about Serbia at all (see Figure 3). A primary narrative is Sputnik V’s widespread and early implementation, revealed by words like already, first, register, early, and approve (RS #417, #1908, #989). A related narrative is that Sputnik V is safe and effective (RS # #417, #1451, #1908, #634). These claims are often overstated and incomplete, and they lack comparisons to the effectiveness of other vaccines (Nogrady, 2021).4One of these claims, namely that Russia is the only country to export vaccine technology, is disinformation. AstraZeneca is produced in multiple countries, which started well before the publication of RS #634. Several articles focused on how Russia is generous with Sputnik V around the world and does not have ulterior motives, as the West claims (RS #1533, #1908, #989); related words in the model are delivery, production, and world. These positive narratives about Russia and Sputnik V were much more frequent than in Ukraina.ru. Sputnik Serbia mentioned Russia 36% more and Sputnik V over three times more than Ukraina.ru.5Combined with all forms, such as “Russian,” “Russian Federation,” etc. This is calculated relative to the overall word count. p < 0.001 for both.

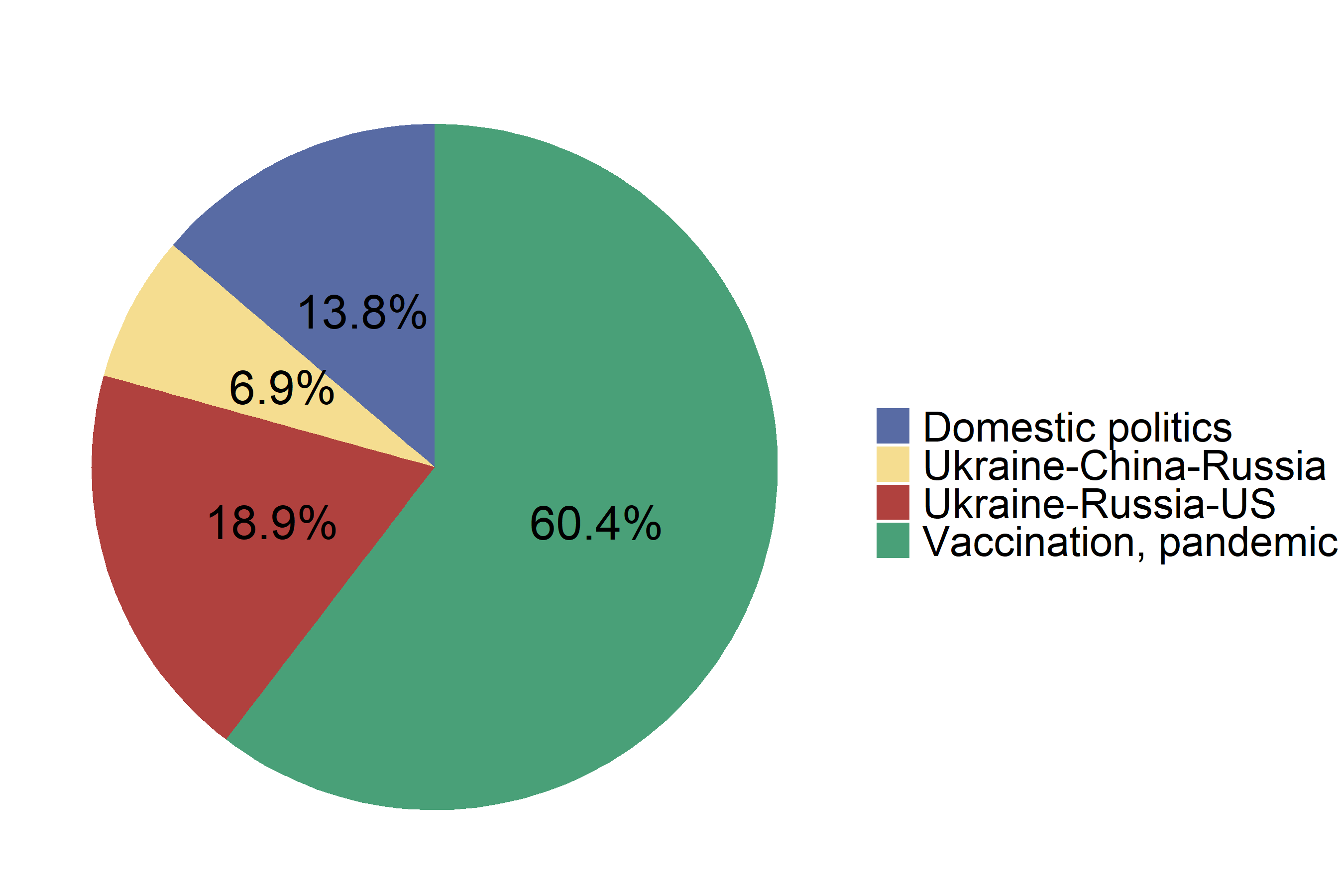

Finding 3: Russian vaccine propaganda in Ukraine also covers Sputnik V positively, but additionally incorporates geopolitics and criticism of the Ukrainian government.

Like in Sputnik Serbia, much of the vaccination and pandemic topic was useful, factual content with words like announce, report, day, data, case, dose, and Ministry of Health (see Figure 2; UK #879, #309). Ukraina.ru editors likely intended to lure readers into thinking Ukraina.ru is an objective outlet so they are more likely to believe the less reliable articles, a technique taught explicitly to propagandists during the Soviet era (Yakovlev, 2015). It is striking that this technique’s target of 60% neutral coverage precisely matches the percentage of articles in this topic (see Figure 4).

The domestic politics topic, which did not exist in Sputnik Serbia coverage, was quite distinct in Ukraina.ru, demonstrated by words like authorities and political, and the names of politicians. Qualitative analysis showed that many articles, including those that blended domestic politics with the vaccination and pandemic topic, criticized the government’s procurement policies: its refusal of Russian vaccines, use of subpar AstraZeneca and Chinese vaccines, and failure to obtain Western vaccines in a timely fashion (UK #44, #900, #1374, 1107, #1004). Articles in this topic also brought vaccines into other domestic issues, including President Zelensky’s unpopularity and repression of critics (UK #1080, #1004).

The two international politics topics, comprising about a quarter of coverage combined, incorporated vaccines into wide-ranging discussions of global issues, as demonstrated by the top positions of Russia, U.S., Biden, China, Donbas, Crimea, and UN (see Figures 2 and 4). Notably, the Ukraine-Russia-U.S. topic highlighted war in the Donbas, both prominent words in the topic. Qualitative analysis showed that the main narrative was that Russia is generous with its vaccines, while the Ukrainian government and the West do not care about Ukrainians’ health (UK #415, #1418, #1107), for example: “In the uncontrolled territories [i.e., the Donbass] people are receiving the vaccine, while the Ukrainian elites essentially threw the people to the whims of fate and themselves got vaccinated secretly in private clinics” (UK #1219). The diversity of the geopolitical themes to which Ukraina.ru ties vaccines differs substantially from the closest equivalent topic in Sputnik Serbia, Russian vaccines, which is limited to praise of Sputnik V and Russia’s generosity distributing it.

Methods

This study seeks to understand how Russia’s approach to propaganda differs when directed at the hostile versus friendly publics. This includes the key narratives and structure of the overall coverage. Ukraine and Serbia serve as good case studies because they are both European, post-communist countries but are polar opposites on the independent variable. Multiple recent head-to-head opinion polls show that the vast majority of the Ukrainian public is anti-Russia, and the vast majority of Serbians are pro-Russia (Hosa & Tcherneva, 2021; Mitchell, 2017). Most directly relevant, the Hosa and Tcherneva (2021) study found that 82% of Ukrainians do not trust Sputnik V and 75% of Serbians do.

The Russian propaganda outlets chosen for this research are Serbian-language Sputnik Serbia and Russian-language Ukraina.ru. Both are subsidiaries of the same Russian government-owned and operated media conglomerate, Rossiya Segodnya (Vedomosti, 2014). Therefore, they are not only both unambiguous mouthpieces for the Russian government but are also led by the same actors within the Russian government, so their narratives are directly comparable.

These sites are appropriate for analysis of Russian propaganda in Ukraine and Serbia because they specifically target each national audience and are influential, albeit in different ways. Ukraina.ru was launched in May 2014, shortly after the annexation of Crimea (Vedomosti, 2014). Therefore, it was explicitly designed to operate in a hostile context. Ukraina.ru propagates fake news stories that appear in Ukrainian outlets and social media, as identified by the Kyiv-based fact checker StopFake (n.d.).6The outlet publishes in Russian, which the vast majority of Ukrainians understand, even if they prefer not to speak it (Matviyishyn, 2020). The Belgrade-based, Serbian-language Sputnik service began in 2015 (Vučićević, 2016). Previous studies have shown that it wields significant influence through partnerships with local media (Brey, 2018; Jonsson, 2018; Stronski & Himes, 2019). Sputnik Serbia and Ukraina.ru play very different roles in the Russian propaganda apparatus namely because of the political differences that motivate this study; by design, there are no outlets in both countries with directly comparable tactics of influencing the public. Further research on the precise audience of these outlets and the way they integrate with the broader propaganda apparatus is needed.

The period of analysis, from December 1, 2020, to November 30, 2021, captured one year since the vaccination campaign began (Delauney, 2021; Ukrainskaya Pravda, 2021). All articles containing the word vaccine7As determined by a search result for that word through each website’s own search function. in this period were scraped from the websites using Python (2,417 articles in Sputnik Serbia and 1,552 in Ukraina.ru). I converted the words to their dictionary form so that all grammatical forms were considered the same word.8For this lemmatization process, I used the Python packages Pymystem3 for Russian and Classla for Serbian. Phrases of up to four words were created such that words typically appearing next to each other, such as Sputnik V, were considered one term.

Quantitative analysis was conducted using the statistical software R. This includes Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling, which creates topics based on the frequency with which words appear in the same text and ranks the most common words in each topic. Human judgement was used to decide on the number of topics that made the model most interpretable. To test and elaborate on quantitative findings, a small sample of twenty articles for each country was qualitatively analyzed. An equal number of articles about each topic was selected randomly from the group of articles within that topic.916 of these were divided evenly between the topics and were selected randomly from articles highly representative of the topic, as the model estimating that over 90% of the content in the article is that topic. After meeting the 90% threshold, the sample is random. An additional four were chosen from articles containing a mix of topics to see how narratives may overlap. Mixed was defined as the model estimating that the topic with the largest represented topic does not comprise more than 60% of the topic.

Topics

- COVID-19

- / Propaganda

- / Russia

- / Vaccines

Bibliography

Barnes, J. E. (2021, August 5). Russian disinformation targets vaccines and the Biden administration. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/05/us/politics/covid-vaccines-russian-disinformation.html

Brey, T. (2018). Russische Medienmacht und Revisionismus in Serbien [Russian media power and revisionism in Serbia]. Südosteuropa Mitteilungen, 58(4), 26–41. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=717288

Delauney, G. (2021, February 10). Covid: How Serbia soared ahead in vaccination campaign. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-55931864

DiResta, R., Shaffer, K., Ruppel, B., Sullivan, D., Matney, R., Fox, R., Albright, J., & Johnson, B. (2018). The tactics and tropes of the Internet Research Agency. New Knowledge. https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/533-read-report-internet-research-agency/7871ea6d5b7bedafbf19/optimized/full.pdf

EU vs Disinfo. (n.d.). Disinfo database: Disinformation about Ukraine. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/disinformation-cases/

Fitzgerald, C. W., & Brantly, A. F. (2017). Subverting reality: The role of propaganda in 21st century intelligence. International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 30(2), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2017.1263528

Global Engagement Center. (2020). Pillars of Russia’s disinformation and propaganda ecosystem. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Pillars-of-Russia%E2%80%99s-Disinformation-and-Propaganda-Ecosystem_08-04-20.pdf

Golan, G. J., & Viatchaninova, E. (2014). The advertorial as a tool of mediated public diplomacy. International Journal of Communication, 8, 1268–1288. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2196

Gray, B., & Edwards, N. (2020, December 10). Russian disinformation popularizes Sputnik V vaccine in Africa. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/russian-disinformation-popularizes-sputnik-v-vaccine-africa

Hosa, J., & Tcherneva, V. (2021, August 5). Pandemic trends: Serbia looks east, Ukraine looks west. The European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/article/pandemic-trends-serbia-looks-east-ukraine-looks-west/

Hyde, L. (2021, August 16). Russian vaccine propaganda is deepening divisions in conflict-riven Ukraine. Coda. https://www.codastory.com/disinformation/ukraine-vaccine-hesitancy/

Jankowitz, N. (2018). The disinformation vaccination. The Wilson Quarterly. https://www.wilsonquarterly.com/quarterly/the-disinformation-age/the-disinformation-vaccination/

Jones, S. (2018, October 1). Going on the offensive: A U.S. strategy to combat Russian information warfare. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/going-offensive-us-strategy-combat-russian-information-warfare

Jonsson, O. (2018). The next front: The Western Balkans. In Popescu, N., & Secrieru, S. (Eds.). Hacks, leaks, and disruptions: Russia’s cyber strategy (Chaillot Paper No. 148) (pp. 85–91). European Union Institute for Strategic Studies. https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/CP_148.pdf

Kara-Murza, V. (2022, January 18). Putin already has at least one client regime in Central Europe. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/01/18/putin-already-has-least-one-client-regime-central-europe/

Kier, G., & Stronski, P. (2021, August). Russia’s vaccine diplomacy is mostly smoke and mirrors. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Kier_and_Stronski_Russia_Vaccine_Diplomacy.pdf

Krainčanić, S. B. (2021, January 21). Proruska kampanja u Srbiji protiv vakcina sa Zapada [The pro-Russian campaign in Serbia against vaccines from the West]. Radio Slobodna Evropa. https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/srbija-proruska-kampanja-protiv-vakcina-sa-zapada/31055431.html

Kuzmanovic, J., Savic, M., & Bratanic, J. (2021, January 22). Vaccines turn into geopolitics in Europe’s most volatile region. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-22/vaccines-turn-into-geopolitics-in-europe-s-most-volatile-region

Lasswell, H. D. (1927). The theory of political propaganda. The American Science Political Review, 21(3), 627–631. https://doi.org/10.2307/1945515

Lenin, V. I. (1902). What is to be done? Dogmatism and freedom of criticism. In Collected works (J. Fineberg & G. Hanna, Trans.; 1961 ed., Vol. 5, pp. 347–530). Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Matviyishyn, I. (2020, June 25). How Russia weaponizes the language issue in Ukraine. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/putin-is-the-only-winner-of-ukraines-language-wars/

Melki, J. & Jabado, M. (2016). Mediated public diplomacy of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria: The synergistic use of terrorism, social media, and branding. Media and Communication, 4(2), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i2.432

Merchant, N. (2022, January 28). US tries to name and shame Russian disinformation on Ukraine. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/wireStory/us-shame-russian-disinformation-ukraine-82526617

Miburo. (2022, February 26). Russia’s lies in four directions: The Kremlin’s strategy to misinform about Ukraine. https://miburo.substack.com/p/russias-lies-in-four-directions-the

Mitchell, T. (2017, May 10). Views on role of Russia in the region, and the Soviet Union. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewforum.org/2017/05/10/views-on-role-of-russia-in-the-region-and-the-soviet-union/

Nogrady, B. (2021, July 6). Mounting evidence suggests Sputnik COVID vaccine is safe and effective. Nature, 595, 339–340. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01813-2

Paul, C., & Matthews, M. (2016). The Russian “firehose of falsehood” propaganda model. Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE198.html

Peisakhin, L., & Rozenas, A. (2018, April 3). When does Russian propaganda work — and when does it backfire? Here’s what we found. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/04/03/when-does-russian-propaganda-work-and-when-does-it-backfire-heres-what-we-found/

Pomerantsev, P. (2015). Nothing is true and everything is possible: The surreal heart of the new Russia. Public Affairs.

Reyting Group. (2021, March 25). Vaccination in Ukraine: Barriers and opportunities. https://ratinggroup.ua/en/research/ukraine/vakcinaciya_v_ukraine_barery_i_vozmozhnosti_18-19_marta_2021.html.

Singer, P. W., & Brooking, E. T. (2018). LikeWar: The weaponization of social media. Mariner Books.

Stiftung, K. A. (2018, March 12). Propaganda and disinformation in the Western Balkans: How the EU can counter Russia’s information war. StopFake. https://www.stopfake.org/en/propaganda-and-disinformation-in-the-western-balkans-how-the-eu-can-counter-russia-s-information-war/

StopFake. (n.d.). Tag: Украина.ру [Tag: Ukraina.ru]. https://www.stopfake.org/ru/tag/ukraina-ru/

Stronski S., & Himes, A. (2019, February 6). Russia’s game in the Balkans. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/02/06/russia-s-game-in-balkans-pub-78235

Sunter, D., & Cappello, J. (2021, February 13). Kremlin sows discord in Western Balkans. CEPA. https://cepa.org/kremlin-sows-discord-in-western-balkans/

Thomas, E., Albert, Z., & Currey, E. (2020, August). Pro-Russian vaccine politics drives new disinformation narratives. Australian Strategic Policy Institute and International Cyber Policy Center. https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/ad-aspi/2020-08/Pro%20Russian%20vaccine%20politics.pdf

Ukraine Crisis Media Center (UCMC). (2021, May 28). Overview of Russian information operations in the framework of COVID-19 pandemic. https://uacrisis.org/en/ru-info-operations-covid-19

Ukrainskaya Pravda. (2021, September 13). За тиждень українцям зробили понад 900 тисяч щеплень проти COVID [In one week over 900,000 Ukrainians were vaccinated against COVID]. https://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2021/09/13/7306926

U.S. Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations (2018, January 10). Putin’s asymmetric assault on democracy in Russia and Europe: Implications for U.S. national security (S. Prt. 115–21). https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FinalRR.pdf

Vedomosti. (2014, May 14). Россия сегодня запускает информационный ресурс Украина.ру [Russia today is releasing the information resource Ukraina.ru]. https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/news/2014/05/14/rossiya-segodnya-zapuskaet-informacionnyj-resurs-ukrainaru

Vučićević, B. (2016, July 12). The growing influence of global media in Serbia. Osservatorio Balkani Caucasia Transuropa. https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Areas/Serbia/The-growing-influence-of-global-media-in-Serbia-172773

Will, L. (2021, May). Propaganda in the age of post-truth: The evolution of political deception. The Yale Review of International Studies. http://yris.yira.org/comments/5108

Yakovlev, V. (2015, May 19). «Гнилая селедка», «большая ложь», «40 на 60» — Владимир Яковлев о приемах пропаганды [“Rotten herring,” “big lie,” “40:60:”: Vladimir Yakovlev on propaganda techniques]. StopFake. https://www.stopfake.org/ru/gnilaya-seledka-bolshaya-lozh-40-na-60-vladimir-yakovlev-o-priemah-propagandy/

Funding

No additional funding was provided.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethics

Institutional review was unnecessary because all data used in this project are publicly available.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RVW6WO

Acknowledgements

I express deep gratitude to Joel Brenner of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology his guidance and comments. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions, most of which were incorporated and significantly improved the article.